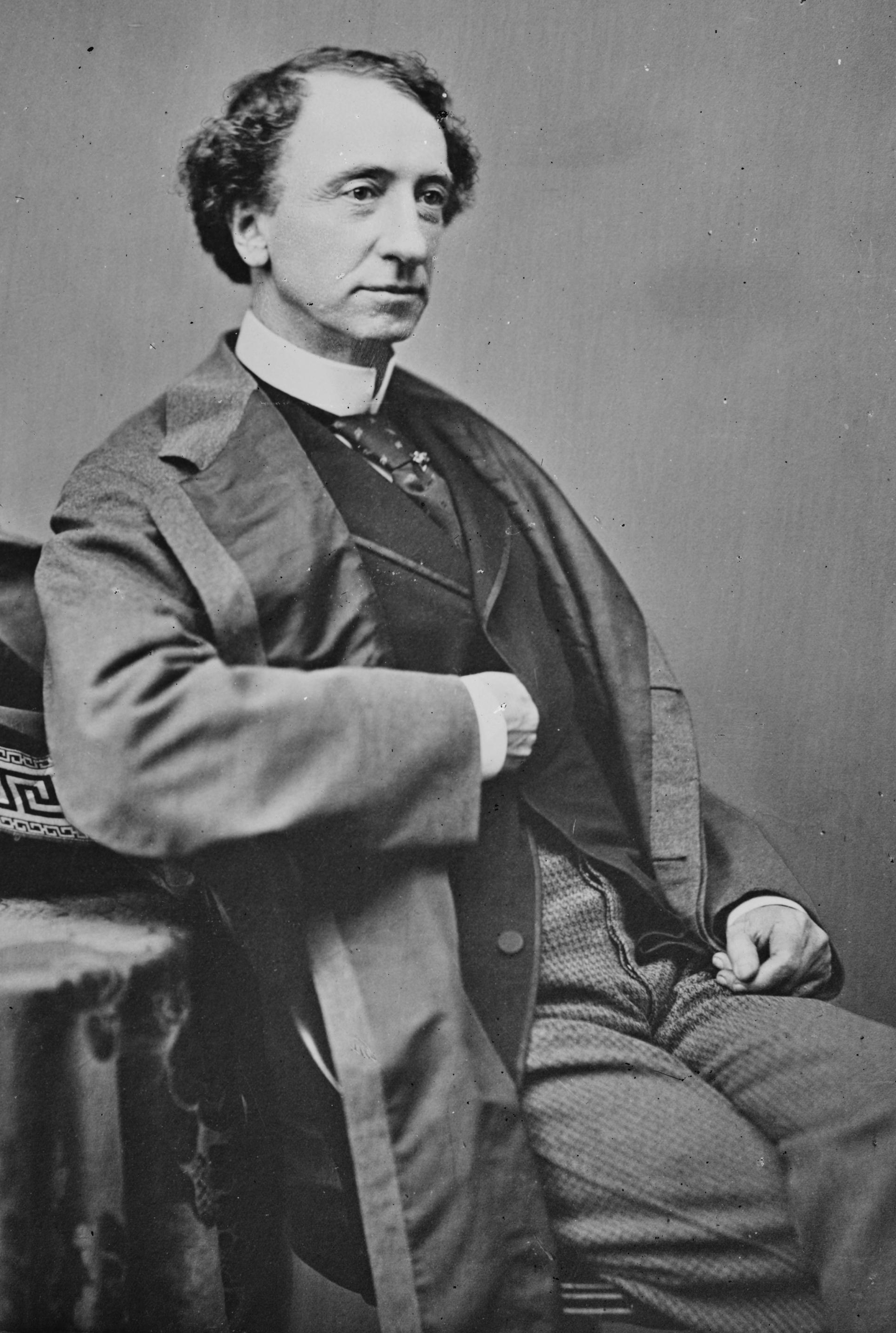

Macdonald, Sir John Alexander (1815-1891), was the first prime minister of the Dominion of Canada. He is often called the father of present-day Canada because he played the leading role in establishing the dominion in 1867. Macdonald served as prime minister from 1867 until 1873 and from 1878 until his death in 1891. He held the office for nearly 19 years, longer than any other Canadian prime minister except W. L. Mackenzie King, who served for 21 years.

Macdonald, a Conservative, entered politics when he was 28 years old. During his long public career, Canada grew from a group of colonies into a self-governing country extending across North America. Macdonald stood out as the greatest political figure of Canada’s early years. He helped strengthen the new nation by promoting western expansion, railway construction, economic development, and harmony between English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians.

A man of great personal charm, Macdonald knew how to make people like him. He was naturally sociable, with a quick wit and a remarkable ability to remember faces. Unlike most politicians of his day, Macdonald made speeches that were colorful and witty. People preferred his talks to the long, dull, and flowery speeches of others.

Early life

Boyhood and education.

John Alexander Macdonald was born on Jan. 11, 1815, in Glasgow, Scotland. He was the son of Helen Shaw Macdonald and Hugh Macdonald, an easygoing and usually unsuccessful businessman. John had an older sister, Margaret, a younger sister, Louisa, and a younger brother, James, who died at the age of 5. John was 5 years old when the family moved to Canada in 1820.

The Macdonalds settled in Kingston, Upper Canada (in present-day Ontario). Hugh opened a small shop, and the family lived above it. The business did not prosper. In 1824, the family moved westward to Hay Bay. They moved to Glenora in Prince Edward County in 1825, then back to Kingston. Hugh tried one business after another, but none brought him success.

As a boy, John became interested in books and was a bright student. He finished his formal schooling in 1829 when he was 14. In 1830, John began to study law with George Mackenzie, a prominent Kingston lawyer. He lived with the Mackenzie family and worked in the law office. In 1833, John learned that a relative, a lawyer in Hallowell, Prince Edward County, was seriously ill. John agreed to take over his practice.

Lawyer.

Macdonald returned to Kingston in 1835. He was admitted to the bar of Upper Canada in 1836. That same year, he took on his first apprentice-lawyer, Oliver Mowat, who later became premier of Ontario and, with Macdonald, one of Canada’s Fathers of Confederation (see Confederation of Canada ).

In 1837, several hundred American supporters of William Lyon Mackenzie, a leading opponent of British rule in Upper Canada, staged a raid into Canada. Macdonald defended some of the raiders who had been arrested. Two Americans were hanged, but the case helped establish Macdonald’s legal reputation. See Rebellions of 1837 ; Mackenzie, William Lyon .

In 1841, Upper Canada (part of present-day Ontario) and Lower Canada (part of present-day Quebec) united to form the Province of Canada. The Province of Canada had one legislative assembly, with an equal number of members from Upper and Lower Canada, also known as Canada West and Canada East.

Kingston, in Upper Canada, became the capital of the Province of Canada. Both the city and Macdonald’s law practice grew prosperous. In 1843, Macdonald began a law partnership with Alexander Campbell. Campbell had been Macdonald’s second apprentice-lawyer and would become another one of the Fathers of Confederation.

Marriages.

On the same day that Macdonald set up his law partnership, he married his cousin Isabella Clark. The Macdonalds had two sons, John, Jr., who died during infancy, and Hugh John, who became premier of Manitoba. In 1844, Isabella became ill. Macdonald and his wife were separated for long periods while Isabella tried to restore her health in the United States. But she died in 1857. The years of his wife’s illness were a strain on John Macdonald, both physically and financially. He remained at Isabella’s bedside as much as possible. But he was also building a law practice and a political career. He often felt he was not giving enough attention to his wife, to his practice, or to politics.

In 1867, Macdonald married Susan Agnes Bernard. The couple had a daughter, Mary.

Early public career

In 1843, at the age of 28, Macdonald was elected an alderman in Kingston. In 1844, he accepted the Conservative nomination in Kingston for a seat in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada. He easily won election.

Macdonald’s associates in the Assembly soon recognized his political abilities. In 1847, he was appointed receiver general in the Conservative administration of William Henry Draper. But Draper’s government was defeated later that year.

For the next few years, Macdonald helped rebuild the Conservative Party. He wanted the party to include men of liberal and conservative views, French-Canadians and English-Canadians, Roman Catholics and Protestants, and rich and poor. A Liberal-Conservative coalition government was formed in 1854 under Conservative leader Sir Allan MacNab. Macdonald served as attorney general in this administration.

Associate provincial prime minister.

In 1856, Macdonald and Etienne P. Tache became dual prime ministers of the Province of Canada. Tache was the senior minister in what was called the Tache-Macdonald government. The next year, Tache retired. Macdonald became senior minister with George E. Cartier as his associate prime minister.

In 1858, the Macdonald-Cartier government suffered a defeat in the Assembly, and the two men resigned as prime ministers. But a week later, the governor general, the British monarch’s representative in Canada, asked Cartier to become senior minister and form a government. With Macdonald’s help, the new government became the Cartier-Macdonald government.

Under an Assembly rule, the cabinet ministers in this government normally would have been required to win reelection to their Assembly seats after being appointed to the cabinet. However, the rule did not apply to ministers who resigned and accepted another cabinet position within a month. To take advantage of this rule, the ministers simply returned to office with new titles. Then they quickly dropped the new titles and resumed their former offices. This avoidance of the need to seek reelection became known as the “double shuffle.” It was legal, but the opposition charged it was dishonest.

The Conservative government was defeated in 1862, although Macdonald had easily won reelection to the assembly from Kingston in 1861. Macdonald served as leader of the opposition party until 1864. The Conservatives won the election that year. Tache came out of retirement, and the second Tache-Macdonald government was formed.

Forming the Dominion.

In the early 1860’s, the northern half of North America was called British North America. It consisted of only a few provinces. Most of the people lived in the east. The Maritime Provinces—New Brunswick, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island—lay along the Atlantic coast. The Province of Canada was next to them on the west. Of these five provinces, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada were older and more developed. Farther west was an expanse of mainly unsettled territory governed by the Hudson’s Bay Company (see Hudson’s Bay Company ). On the west coast lay British Columbia, then a British colony.

For several years, the British provinces in North America had considered the idea of confederation. Several factors gave force to this idea. They included the instability of provincial governments, the desire to expand to the west, and fear of U.S. expansion.

The Province of Canada led the confederation movement. In the Province of Canada, Macdonald formed a coalition with his opponent, Reform Party leader George Brown, to achieve confederation.

From 1864 to 1867, Macdonald led in planning confederation. In September 1864, he attended a conference in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, to present the confederation plan to the Maritime Provinces. In October, delegates from all the provinces gathered at a second conference in Quebec. At this meeting, Macdonald was largely responsible for drawing up the Quebec Resolutions, the plan for confederation.

New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and the Province of Canada approved the idea, but Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island rejected it. Final details were agreed upon at a conference in London in 1866. In 1867, the British Parliament passed the British North America Act, which brought the Dominion of Canada into being (see British North America Act ). The new nation had four provinces: Ontario (previously Upper Canada), Quebec (previously Lower Canada), New Brunswick, and Nova Scotia. The governor general, Viscount Monck, asked Macdonald to become prime minister.

Queen Victoria knighted Macdonald for his leadership of the confederation movement. The announcement of his knighthood came on July 1, 1867, the first day of the Dominion’s existence. A general election, in which Macdonald and the Conservatives triumphed, was held in August and September, and the new Parliament assembled on Nov. 6, 1867.

Macdonald’s first administration (1867-1873)

Completing the Dominion.

Sir John A. Macdonald took office as prime minister of the Dominion of Canada on July 1, 1867. His goal was to enlarge the Dominion into a unified nation extending across the continent.

In 1869, the Canadian and British governments agreed with the Hudson’s Bay Company to purchase the company’s lands. The company was paid 300,000 pounds (about $11/2 million) and 5 percent of the land south of the North Saskatchewan River. But the Metis (persons of mixed white and Indian descent) in the purchased territory rebelled. They were led by Louis Riel. They feared that an onrush of settlers would deprive them of their lands. Many Canadians also thought the United States might annex this land. Parliament passed the Manitoba Act in 1870, and in July 1870, Manitoba became Canada’s fifth province and the first province to be added to the Dominion of Canada (see Red River Rebellion ). British Columbia became the sixth province in 1871, and Prince Edward Island the seventh in 1873.

In 1871, delegates from the United Kingdom and the United States held a conference in Washington, D.C. Macdonald attended the meeting as the Canadian member of the British delegation. He tried to obtain a trade agreement with the United States, but was not successful. Nevertheless, Macdonald signed the Treaty of Washington. Among other points, this treaty granted the United States extensive fishing rights in Canadian waters. Macdonald felt that refusal to sign the treaty might encourage the United States to use force to win its demands. He was always careful not to endanger the young Canadian nation. See Washington, Treaty of .

The Pacific Scandal.

Next, Macdonald turned to the issue of building a transcontinental railroad to unify Canada. The construction of such a railroad had been one of the terms of British Columbia’s entry into the Confederation.

Two financial groups competed with each other to build the line. Then, in 1873, it was learned that Sir Hugh Allan, head of one of the groups, had contributed a large sum of money to help reelect Macdonald’s government in the 1872 election. Some Liberal members of Parliament charged there had been an “understanding” between Allan and the government. They accused the government of giving Allan a charter to build the railroad because he had contributed to the Conservatives’ election fund.

The incident became known as the Pacific Scandal. Macdonald claimed that he was innocent. But evidence showed that he and some of his associates had received a large sum of money from Allan and spent it illegally during the 1872 election. Macdonald resigned as prime minister. He offered to resign as head of the Conservative Party, but his supporters persuaded him to remain in that post. The Conservative Party lost the 1874 election, although Macdonald won reelection to Parliament from Kingston. Alexander Mackenzie, the leader of the Liberal Party, succeeded Macdonald as prime minister.

The National Policy.

After the 1874 election, Macdonald led the opposition party in the House of Commons. He began to rebuild the Conservative Party. Macdonald favored a program of economic nationalism that he called the National Policy. This program called for developing Canada by protecting its industries against competing products from other countries.

The idea appealed to Canadians, especially because a depression had begun in 1873. On the strength of the National Policy, the Conservatives defeated the Liberals in the 1878 election. They returned to power with an election victory in almost every province.

Macdonald’s second administration (1878-1891)

National prosperity.

Macdonald began another term as prime minister on Oct. 17, 1878. In 1879, the government began putting the National Policy into effect by placing tariffs on a variety of goods. Macdonald again began to push for construction of a transcontinental railroad. With government support, a new company was formed. By November 1885, the Canadian Pacific Railway had been completed to the Pacific Ocean. Macdonald had achieved his program of western expansion, railway construction, and economic nationalism.

Threats to Canadian unity.

Macdonald had worked long and hard to build a unified Canadian nation. But beginning in 1885, a number of political developments seriously threatened this unity.

In 1885, Louis Riel led the Metis of northwest Canada in a second rebellion. When Riel finally surrendered, he was found guilty of treason and sentenced to hang. The sentence caused severe bad feeling between French-Canadians and English-Canadians. For a time, the issue threatened to split the confederation. However, Macdonald refused to give in to Riel’s supporters. “He shall die though every dog in Quebec bark in his favour,” Macdonald is said to have declared. Riel was hanged in November 1885. See North West Rebellion .

Macdonald next faced an attack by the provincial premiers against his program for a strong central government. In 1887, five of the premiers met at a conference in Quebec. They proposed changes in the British North America Act that would decentralize the Canadian government. Neither the Canadian government nor British authorities seriously considered the premiers’ demands. However, the conference showed the growing strength of provincial resistance to federal centralization.

Still another blow to Macdonald was the depression of 1883. The National Policy had not produced all the expected results. In 1886 and 1887, a demand arose for a change in Canada’s financial policy. Some people favored Imperial Federation with the United Kingdom. Supporters of this philosophy believed that Canada and other members of the British Empire should formally agree to trade with and defend one another. Others spoke of a commercial union with the United States. Macdonald opposed both proposals.

In the 1891 election, the Liberals adopted a party platform calling for unrestricted reciprocal trade with the United States (see Reciprocal trade agreement ). The 76-year-old Macdonald fought this proposal with all the strength he could muster.

“Shall we endanger our possession of the great heritage bequeathed to us by our fathers,” he asked the Canadian people, “and submit ourselves to direct taxation for the privilege of having our tariffs fixed at Washington, with the prospect of ultimately becoming a portion of the American Union? … As for myself, my course is clear. A British subject I was born, a British subject I will die.” With this appeal, Macdonald won his last election.

Death.

The strain of campaigning proved severe for Macdonald. He suffered a stroke on May 29, 1891, and died on June 6 in Ottawa. Macdonald was buried near his mother in Kingston, Ontario.