Madison, James (1751-1836), the fourth president of the United States, is often called the Father of the Constitution. He played a leading role in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Madison helped design the system of separation of powers and the checks and balances that operate among Congress, the president, and the Supreme Court. He also helped create the U.S. federal system, which divides power between the central government and the states. Madison’s presidency lasted from 1809 to 1817.

Madison served his home state—Virginia—and the United States in many roles over his 40 years in public life. He was a close friend of Thomas Jefferson, who also was a Virginian. The two men worked together for American independence during the American Revolution (1775-1783). After the war, they continued to work for liberty and the principles of republicanism. Following the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Madison joined with statesmen Alexander Hamilton and John Jay to write a series of essays called The Federalist. Jefferson called the series “the best commentary on the principles of government ever written.”

During the 1790’s, Madison and Jefferson resisted efforts by Hamilton to establish a national bank. Hamilton, as secretary of the treasury, had wanted to provide government support to manufacturers. Madison and Jefferson, on the other hand, wanted the United States to remain a farming republic. They believed Hamilton’s measures would give the central government unnecessary and improper powers. In 1792, Madison and Jefferson organized people who opposed Hamilton’s policies into the Democratic-Republican Party. The party was the forerunner of today’s Democratic Party.

Before Madison became president in 1809, he served as secretary of state under President Jefferson. Both as secretary of state and as president, Madison tried to obtain fairer trade policies with Britain. He also tried to keep the United States from being drawn into conflicts between European countries. In 1812, however, President Madison led the United States into war against the United Kingdom after the British had interfered with U.S. shipping. During the War of 1812, British troops captured Washington, D.C., where they burned the Capitol, the White House, and other government buildings

Madison retired from the presidency in 1817. He and his wife Dolley then returned to their Virginia home in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Madison continued to study politics and host the many guests who came to visit the couple.

Early life

James Madison was born in the home of his mother’s parents on March 16, 1751 (March 5 by the calendar then in use). The home was at Port Conway, Virginia, about 12 miles (19 kilometers) from Fredericksburg. James was the eldest of 12 children. He grew up at Montpelier, the family estate near what is now Orange, Virginia. James would inherit many enslaved Black people who worked at Montpelier.

James, known to his friends as “Jemmy,” was a quiet child of slight build and frail health. He was filled with a lively passion for learning. As a youth, he studied with schoolmaster Donald Robertson. Robertson taught him grammar, arithmetic, algebra, geometry, geography, French, Italian, Latin, and some Greek. At the age of 18, Madison entered the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University). Madison studied hard and completed the regular course at the college in two years. He graduated in 1771.

Political and public career

Entry into politics.

Madison entered politics in 1774, when he was elected to the Committee of Safety in Orange County, Virginia. Committees of this kind provided local government in the days when the British colonial government was crumbling. In 1776, Madison helped draft a new Virginia constitution and the Virginia Declaration of Rights. Other colonies later drew upon these documents in writing their own constitutions.

Madison served in Virginia’s revolutionary assembly in 1776, when he met Thomas Jefferson. The two men soon began a lifelong friendship. In 1779, Madison was elected to the Continental Congress. Madison took his seat in the Congress in March 1780. In those days, the Congress had no power to raise taxes and found it difficult to collect debts. Madison favored increasing the powers of the Congress to bring about greater financial and political stability for the new nation. Madison’s fellow delegates recognized him as a conscientious and able legislator.

Virginia assemblyman.

Madison returned to his home state in 1783. He then served in the Virginia House of Delegates from 1784 to 1786. In this role, he continued a struggle for religious liberty that Jefferson had begun in Virginia. Madison opposed fellow assemblyman Patrick Henry, who favored government support for teachers of the Christian religion. Madison argued that religion “must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man.” In 1786, the assembly passed Virginia’s Statute of Religious Freedom. Madison wrote to Jefferson that the statute had “extinguished forever the ambitious hope of making laws for the human mind.”

During his time in the assembly, Madison argued in support of the gradual abolition of slavery. He also worked to defeat a bill that would have prohibited the manumission (freeing, by a slaveowner) of enslaved people.

In 1786, Madison attended the Annapolis Convention in Maryland. The meeting failed to resolve the nation’s problems dealing with interstate commerce. Instead, the attendees called for another convention to meet in Philadelphia the following year to discuss amending the Articles of Confederation. The Articles had served as the basic law of the United States since 1781.

Constitutional Convention.

Madison represented Virginia at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Although only 36 years old, he took a leading role in the debates. Madison had prepared for the convention for months. He studied the history, politics, and structures of ancient and modern republics and confederations. He hoped to find a remedy to the problems that had destroyed popular governments throughout the ages.

Madison drafted the Virginia Plan for the union. This plan, also called the Randolph Plan, foreshadowed the Constitution that the convention eventually adopted. It called for a strong central government and a bicameral (two-house) legislature based on population.

Madison’s work at the convention won him great respect. Georgia delegate William Pierce observed that “every Person seems to acknowledge his greatness. He blends together the profound politician, with the Scholar.” Madison also kept a more complete record of the convention’s debates than did anyone else in attendance. During the long, hot Philadelphia summer of 1787, Madison never missed a day at the convention.

The Constitutional Convention’s delegates agreed that each state should hold a special convention to discuss and vote on the Constitution. Madison served as a member of the convention that was called in Virginia. He also joined Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in writing The Federalist, a series of letters in favor of ratification. Scholars still consider these letters the most authoritative explanation of the American constitutional system.

During the debates over the Constitution, Madison expressed concerns with the emergence of factions—political groups that, he believed, united for unjust goals. Madison described how factions had contributed to the destruction of past governments. He supported a system of separation of powers and checks and balances to protect citizens from factions within the government.

Congressman.

Madison’s efforts on behalf of the Constitution cost him the support of Virginians who opposed a stronger union. In 1788, united opposition in the Virginia legislature kept him from winning a seat in the first United States Senate. Early the next year, however, Madison defeated James Monroe in an election for the U.S. House of Representatives.

As a congressman, Madison proposed resolutions for organizing the Departments of State, Treasury, and War. He also drafted much of the first tariff act, which set up U.S. taxes on imports. Most important, Madison was largely responsible for drafting the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, the Bill of Rights (see Bill of rights).

At first, Madison supported many policies of President George Washington’s administration. But he gradually came to oppose the financial plans of Washington’s treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton. Madison believed that Hamilton’s plans favored the wealthy few at the expense of ordinary citizens and farmers. He also believed that Hamilton was not following the Constitution as it was understood by the American people who had ratified it. As a result, Madison argued strongly against Hamilton’s economic and political policies. In the early 1790’s, Madison and Jefferson formed a movement that became the Democratic-Republican Party, in opposition to the Hamilton-led Federalists.

In Philadelphia in 1794, Madison met and married Dolley Payne Todd, a young widow. By 1797, he had become weary of politics and retired to his estate. But in 1798, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, a series of laws intended to silence opposition to an expected war with France (see Alien and Sedition Acts). Madison was outraged. He drafted the Virginia Resolutions of 1798, calling upon the states to oppose the acts and declare them unconstitutional. Madison was elected to the Virginia legislature in 1799 and 1800 and led the fight against what he considered Federalist efforts to undermine basic human rights.

Secretary of state.

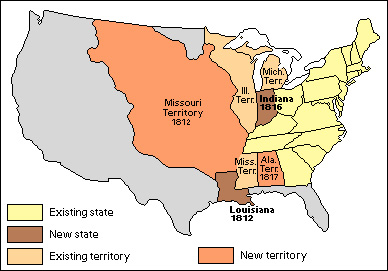

Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801, and Jefferson appointed Madison secretary of state. The purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France was the most important success in foreign relations during Jefferson’s presidency (see Louisiana Purchase). The United States went to war with the Barbary States, along the coast of northern Africa, between 1801 and 1805. The Barbary States had licensed sea raiders to attack U.S. and other ships in the Mediterranean Sea (see Barbary States).

Relations with the United Kingdom and France were also a chief concern. Madison and Jefferson struggled to make the two countries respect the rights of Americans on the high seas. The British and French were fighting each other in the Napoleonic wars, and each had blockaded the other’s coast. American ships that tried to trade with either country were stopped by warships of the other. Many American seamen were seized and forced to serve on British or French warships. Jefferson and Madison supported the Embargo Act of 1807, which prohibited all ships from entering or leaving American ports. The act was intended to protect American interests and to avoid war. Ultimately, however, the embargo hurt Americans economically and was repealed in 1809. Congress then passed the Non-Intercourse Act, which opened trade with all countries except the United Kingdom and France

As Jefferson neared the end of his presidency, he favored Madison to succeed him. In the presidential election of 1808, Madison received 122 electoral votes to 47 for the Federalist candidate, former minister to France Charles Cotesworth Pinckney. For votes by states, see Electoral College (table). Madison’s running mate was George Clinton of New York.

Madison’s first administration (1809-1813)

Events leading to war.

When Madison became president, trade issues with the United Kingdom and France remained the government’s chief concern. In 1810, Congress passed a bill that reopened trade with the two countries. The law stated that if either the United Kingdom or France ended its attacks on U.S. ships, the United States would stop trading with the other country.

French Emperor Napoleon I announced that France would comply, so Madison halted trade with the United Kingdom. But Napoleon issued secret orders that maintained the French blockade against American shipping. At the same time, the British were stirring up Indigenous (native) tribes to fight Americans in the West. The British also continued to seize American seamen and ship cargoes.

In Congress, a group of young people known as the “War Hawks” pressured Madison to take military action. The group included Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

“Mr. Madison’s War.”

Madison knew the United States was unprepared for war. He also knew that New England merchants worried that war would destroy trade. But Madison felt that people outside New England wanted action, and that the nation could tolerate no more insults from the British. He finally recommended war, and Congress approved it on June 18, 1812. The Federalists opposed the War of 1812. They called it “Mr. Madison’s War.”

A few months after the start of the war, Madison was reelected president. He received 128 electoral votes to 89 for Mayor DeWitt Clinton of New York City. Madison’s running mate was Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts.

Madison’s second administration (1813-1817)

Progress of the war.

At the start of the war, the British Navy clamped on a blockade that the small U.S. Navy could not break. In 1812, American land forces attacked Canada—at that time a British possession—but were unsuccessful. The fight for Canada continued for two years, with no decisive victories on either side. By 1814, Napoleon was defeated in Europe. The United Kingdom then sent experienced troops to Canada, ending American hopes for conquest.

In the summer of 1814, American forces under General Winfield Scott fought the British to a standstill at Chippewa and Lundy’s Lane in southern Ontario. On August 24, British troops burned the Capitol, the White House, and other public buildings in Washington, D.C. Only heroic resistance at Fort McHenry kept the British from capturing Baltimore.

In September 1814, American forces stopped an invasion of British troops moving south down the western shore of Lake Champlain. Early in 1815, General Andrew Jackson won a stunning victory at New Orleans. The War of 1812 ended with the Treaty of Ghent, which went into effect in February 1815. It settled none of the problems that had caused the war, but it preserved American territorial integrity. (see Ghent, Treaty of; War of 1812).

In 1814 and early 1815, before the end of the war, New England Federalists had held a closed meeting known as the Hartford Convention. The convention passed resolutions against the war. It also proposed making New England more independent of the federal government. Many people believed that the convention was planning secession of the New England states. As a result, the Federalist Party was branded as unpatriotic. It fell apart as a national organization shortly after the election of 1816.

The growth of nationalism.

Albert Gallatin, Madison’s first secretary of the treasury, believed that the War of 1812 had “renewed and reinstated the national feeling of character which the Revolution had given and which was daily lessening.” He said the people “are more American; they feel and act more as a nation.” The end of the war ushered in “the era of good feeling.” With the end of the Federalist Party, political conflicts were submerged within the Democratic-Republican Party.

During the two years after the war, trade expanded, and the country experienced great economic growth. In 1816, Madison signed a bill that created the country’s second national bank. The first such bank had operated from 1791 to 1811. Changes in federal policy also made it easier for settlers to buy frontier land, and the rate of westward migration increased. In addition, Madison approved the tariff of 1816, which aimed to protect American industries.

Life in the White House.

During the early years of Madison’s presidency, Dolley Madison hosted extravagant parties. She served elaborate dinners and would surprise her guests with delicacies.

The British invasion of the capital and the burning of the White House drove the Madisons from Washington. When they returned, they established a new residence in the Octagon House, a private home just west of the White House. In 1815, they moved to a house on the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 19th Street. Dolley Madison resumed her busy social life but longed to reoccupy the White House. However, reconstruction work proceeded slowly. The Executive Mansion was not ready for occupancy until nine months after Madison left office in 1817.

Later years

In retirement, Madison busied himself with the affairs of his estate. Many visitors came to Montpelier to share in Madison’s company and conversation. One of these visitors was Madison’s dear friend Thomas Jefferson. Madison honored a request from Jefferson to look after Jefferson’s reputation after he died. Following Jefferson’s death in 1826, Madison became rector (president) of the University of Virginia, which Jefferson had founded. In 1829, Madison attended the Virginia Constitutional Convention, a meeting to revise the state’s constitution.

Madison continued to speak out about the principles of liberty and self-government. Many of Madison’s comments came in response to the views of John C. Calhoun, who was vice president from 1825 to 1832. Madison especially opposed Calhoun’s ideas on states’ rights—particularly the idea that a state should be able to nullify (declare illegal) acts of the federal government. Madison also promoted a just understanding of human rights and criticized the institution of slavery.

Madison died at Montpelier on June 28, 1836. Late in his life, he had penned a short piece called “Advice to My Country,” to be read after his death. “The advice nearest to my heart and deepest in my convictions,” Madison wrote, “is that the Union of the States be cherished and perpetuated. Let the open enemy to it be regarded as a Pandora with her box opened; and the disguised one, as the Serpent creeping with his deadly wiles into Paradise.”

Dolley Madison returned to Washington, where she lived until her death in 1849. The Madisons are buried in a family plot near Montpelier.