Magellan << muh JEHL uhn >>, Ferdinand (1480?-1521), was a Portuguese sea captain who led the first expedition that sailed around the world. He was the first European to cross the Pacific Ocean, Earth’s largest ocean. Magellan did not live to complete the voyage around the world, but his leadership made the entire expedition possible. Many scholars consider it the greatest navigational feat in history.

Early life

Magellan was born about 1480 in northern Portugal. His name in Portuguese was Fernao de Magalhaes. His parents, who were members of the nobility, died when he was about 10 years old. At the age of 12, Magellan became a page to Queen Leonor. Such a position commonly served as a means of education for sons of the Portuguese nobility. At the royal court, Magellan learned about the voyages of Vasco da Gama of Portugal and other explorers.

Magellan first went to sea in 1505, when he sailed to India with the fleet of Francisco de Almeida, Portugal’s first viceroy to that country. In 1506, Magellan went on an expedition sent by Almeida to the east coast of Africa to strengthen Portuguese bases there. The next year, he returned to India, where he participated in trade and in several naval battles against Turkish fleets.

In 1509, Magellan sailed with a Portuguese fleet to Melaka, a port city in what is now Malaysia. The Malays attacked the Portuguese who went ashore, and Magellan helped rescue his comrades.

In 1511, Magellan took part in an expedition that conquered Melaka. Following the conquest, a Portuguese fleet continued on to the Spice Islands (also known as the Molucca Islands), which lay east of Melaka. Portugal then began trading with the islands. Although Magellan did not sail to the Moluccas, his close personal friend Francisco Serrao went along on the voyage. He wrote to Magellan, describing the route and the island of Ternate. Serrao’s letters helped establish in Magellan’s mind the location of the Spice Islands, which later became the destination of his great voyage.

Magellan returned to Portugal in 1513. He then joined a military expedition to Morocco. On this expedition, Magellan suffered a wound that made him walk with a limp for the rest of his life.

Voyage around the world

Planning the expedition.

After returning to Portugal from Morocco, Magellan studied astronomy and navigation for about two years in Porto, in northern Portugal. There, he met Ruy Faleiro, an astronomer and geographer who strongly influenced his ideas. Magellan’s studies convinced him that he could reach the Spice Islands by sailing west around the southern tip of South America. He believed such a route would be shorter than the eastward voyage around the southern tip of Africa and across the Indian Ocean.

Magellan sought the support of King Manuel I of Portugal for his westward voyage. But Manuel refused to support the proposed journey. Magellan and Faleiro had concluded from their studies that the Spice Islands lay in territory that had been awarded to Spain in 1494 (see Line of Demarcation). Therefore, Magellan decided to seek support for his plans from the king of Spain.

In 1517, Magellan and Faleiro traveled to Spain. There, they presented to King Charles I their idea of sailing westward to reach the Spice Islands. The next year, Magellan persuaded the king to support such a voyage. The Spanish had not yet explored the region in which the Spice Islands lay, and Spain would profit if Magellan were to prove that the Moluccas lay in Spanish waters. Charles promised Magellan one-fifth of the profits from the voyage to the Spice Islands, plus a salary.

Preparations for the expedition took more than a year. The Spaniards became suspicious of Magellan because he was Portuguese and recruited many Portuguese sailors. As a result, the king forced Magellan to replace most of the Portuguese with Spaniards and crewmen of various other nationalities.

The voyage begins.

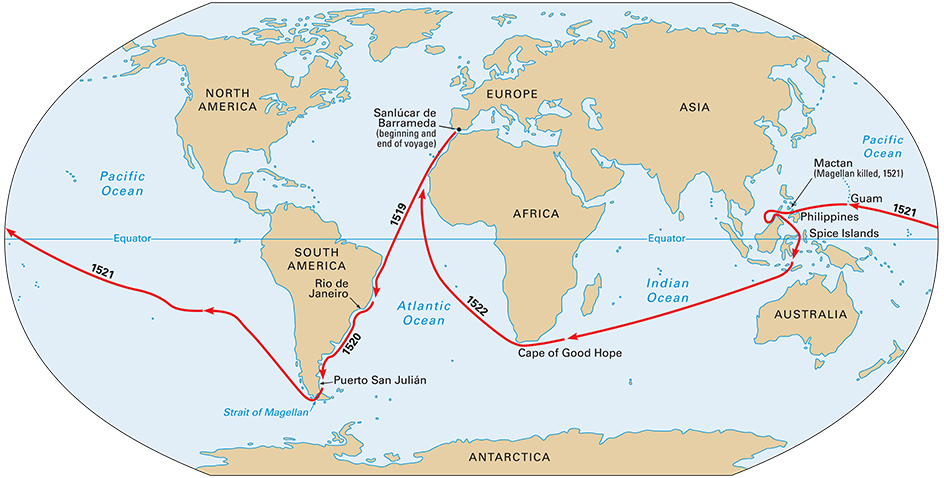

The fleet sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to the coast of Brazil. The ships then followed the South American coast to the bay where Rio de Janeiro now stands. They remained there for two weeks and then sailed south in search of a passage to the Pacific Ocean. However, the ships could not find a passage before the end of summer in the Southern Hemisphere. In late March 1520, Magellan’s fleet anchored for the winter at Puerto San Julian, in what is now southern Argentina.

During the winter, a storm destroyed the Santiago. In addition, a mutiny broke out shortly after the men set up their winter quarters. Magellan and loyal crew members put down the mutiny and executed the leader. They also marooned two other mutineers when the fleet sailed again.

Magellan and his crew resumed their voyage on Oct. 18, 1520. Three days later, they discovered the passage to the Pacific—a passage known ever since as the Strait of Magellan. As the fleet sailed through the strait, the crew of the San Antonio mutinied and returned to Spain. On November 28, the three remaining ships sailed out of the strait and into the ocean. Magellan named the ocean the Pacific, which means peaceful, because it appeared calm compared with the stormy strait.

Sailing across the Pacific

involved great hardship for Magellan and his crew. No Europeans had sailed across the Pacific before them. Consequently, the islands in the Pacific had no established stations at which they could resupply their ships. They sailed for 98 days without seeing any land except two uninhabited islands. Their food gave out, and their water supply became contaminated. They ate rats, oxhides, and sawdust to avoid starvation. Most of the crew suffered from scurvy, a disease caused by the lack of vitamin C in their diet. Nineteen men died before the fleet reached Guam on March 6, 1521.

Conflicts with the people of Guam and the nearby island of Rota prevented Magellan from fully resupplying his ships. But the crew seized enough food and water to continue on to the Philippines.

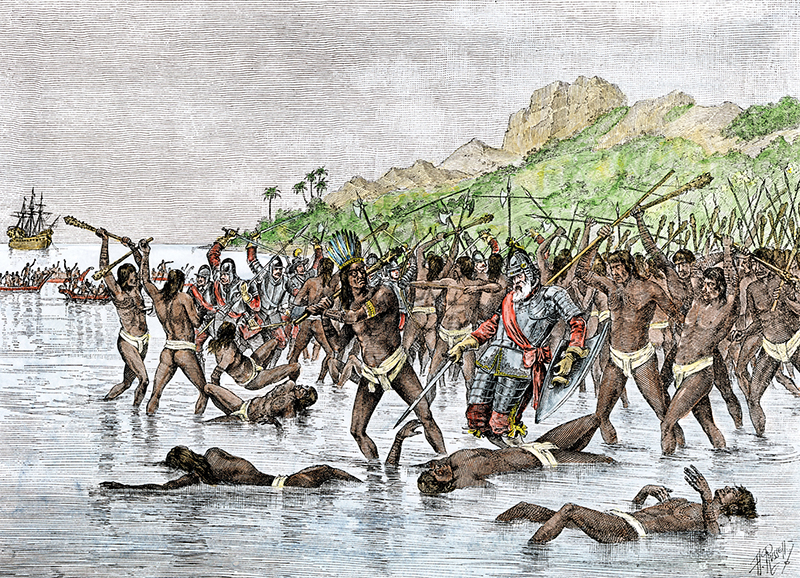

Magellan and his crew remained in the Philippines for several weeks, and close relations developed between them and the islanders. Magellan took special pride in converting many of the people to Christianity. On April 27, 1521, Magellan was killed when he took part in a battle between rival Filipino groups on the island of Mactan.

The end of the voyage.

After the battle on Mactan, only about 110 of the original crew members remained—too few to man three ships. Therefore, the men abandoned the Concepción, and the two remaining vessels sailed southward to the Spice Islands. There, the ships were loaded with spices. The leaders of the fleet then decided that the two ships should make separate return voyages.

The Trinidad, under the command of Gonzalo Gomez de Espinosa, tried to sail eastward across the Pacific to the Isthmus of Panama. Bad weather and disease disrupted the voyage, and more than half of the crew of the Trinidad died. The surviving members of the crew were forced to return to the Spice Islands, where the Portuguese imprisoned them.

Only the Victoria, commanded by Juan Sebastián de Elcano, successfully continued its westward voyage back to Spain. Like the Trinidad, the Victoria experienced great hardship, and many of the crew died of malnutrition and starvation. The Victoria finally reached Sanlucar de Barrameda on Sept. 6, 1522, nearly three years after the voyage had begun. Only de Elcano and 17 other survivors returned with the ship.

Results of the voyage.

One of the crew members who returned with de Elcano was an Italian named Antonio Pigafetta. He had faithfully written down the events of the voyage, and his journal is the chief source of information about the expedition. Pigafetta praised Magellan for his courage and navigational skill. However, nearly everyone else at the time gave de Elcano the credit for the voyage. The Portuguese considered Magellan a traitor, and the Spanish resented him.

Magellan proved that it was possible to reach the Spice Islands by sailing westward. The discovery of the Strait of Magellan led to future European voyages across the Pacific and around the world. Magellan also proved that the Spice Islands actually lay in Spanish waters. As a result, Portugal had to pay Spain a large sum of money to keep the islands in Portuguese possession.

See also Exploration (Magellan’s globe-circling expedition).