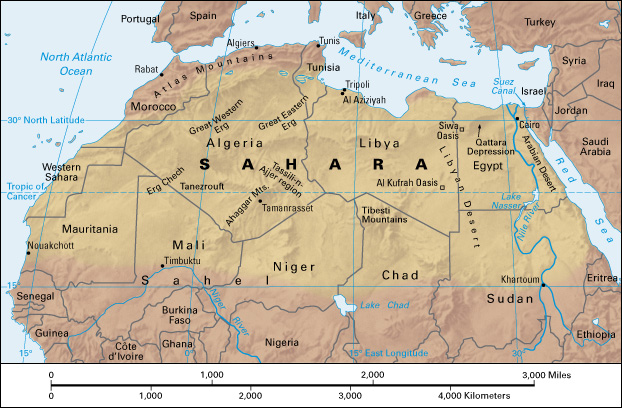

Mali << MAH lee >> is a large country in western Africa. The Sahara, Africa’s great desert, covers the northern half of the country. Rolling grassland spreads across most of the rest of Mali.

Mali is a poor, agricultural country. At times, droughts have led to large numbers of deaths of people and animals. Most of the people of Mali live in small rural villages and farm for a living. Many of the country’s farmers produce only enough food for their own families. Many others raise livestock on the edge of the desert. Fishing in the country’s rivers and lakes is also an important economic activity. Mali’s mineral and water resources are largely undeveloped. Manufacturing and mining contribute relatively little to the economy.

From about the A.D. 300’s to the late 1500’s, one or more of three powerful African empires—Ghana, Mali, and Songhai—thrived in what is now Mali. France ruled Mali from 1895 to 1959. Mali became an independent nation in 1960. Its name in French, the official language, is République du Mali (Republic of Mali). Bamako is Mali’s capital and largest city. See Bamako.

Government.

The president, Mali’s top government official, is elected by the people to a five-year term. The president may serve a maximum of two terms. The president appoints a prime minister, who in turn appoints other government ministers to carry out the day-to-day operations of the government. Mali has a 147-member legislature called the National Assembly. The members are elected directly by the people to five-year terms.

Mali’s court system includes a Supreme Court, a Constitutional Court, and lower courts. For purposes of local government, Mali is divided into ten regions and the District of Bamako.

People.

The Mandinka make up about half of Mali’s population. There are three major Mandinka subgroups—the Bambara, Malinke, and Soninke. The Fulani make up about 15 percent of the population. Other large ethnic groups in Mali include the Dogon, Songhai, and Voltaic peoples. Mali also has a small number of Tuareg and Moors.

About 80 percent of Mali’s people speak a language in the Mande language group. Bambara is the most common Mande language. In addition, the various ethnic groups speak their own local languages. The Fulani and a related people called the Toucouleur speak Fulani (also called Fula or Fulfulde). The Moors speak Arabic, and the Tuareg use a Berber language. French, the official language, is spoken in government offices and schools.

Loading the player...Malian contemporary music

The vast majority of Mali’s people are Muslims (followers of Islam). Others practice traditional African religions. A small percentage of the people are Christians.

Many of Mali’s people reside in small rural villages in southern Mali and grow crops for a living. They generally work on plots next to the villages. Many can raise only enough food for their own use. Their foods include cassava, corn, millet, rice, sorghum, and yams. Most Malian farmers cannot afford agricultural machinery, and so they use traditional methods for almost all their work. In Mandinka villages, related families live close together in round huts with cone-shaped thatched roofs.

A majority of Mali’s Fulani farm for a living. They live in round, earthen houses with thatched roofs, or sometimes in rectangular brick homes. Others raise cattle in the Sahel, a semidesert region, and in the southern grasslands. These herders live in dome-shaped huts made of branches covered with mats of grass or leaves.

Many of Mali’s Moors and Tuareg are nomads. The nomads herd cattle, goats, sheep, and donkeys back and forth across the Sahel and Sahara in search of water and pasture for grazing. They live in portable tents made of grass matting or animal skins. Their basic foods include dates and millet. They travel in groups led by marabouts (holy men), and they are strongly independent.

Women play a key role in farming in Mali. They help plant and harvest crops and raise livestock. The government has set up modern job training programs for women. But relatively few have enrolled because of their heavy workloads and family responsibilities.

Many of Mali’s people suffer from a lack of education. The majority of Mali’s adults cannot read and write, and many of the country’s school-age children do not attend school. The University of Mali provides higher education. But many Malian students prefer to pursue higher degrees and professional training in other nations, mainly France and Senegal.

Mali is also challenged by poor health conditions. Malaria is widespread in Mali and is a chief cause of death among children. Mali has only a few hundred doctors to serve its entire population. Most of them work in urban areas.

Land and climate.

Mali has three main land regions: the harsh Sahara in the north, the semidesert Sahel in central Mali, and rolling grasslands in the south. Mali has few mountains. Its highest point, Hombori Tondo, a mountain in the south, rises 3,789 feet (1,155 meters) above sea level.

The Senegal and Niger are Mali’s chief rivers. Most of the country’s people live in villages and urban areas along or near these rivers and their branches. The Senegal flows west from southwestern Mali to the Atlantic Ocean. The Niger enters Mali near Bamako and flows northeast into the interior delta, Mali’s most fertile area. It then makes a great turn called the Niger Bend and flows southeast into the country of Niger. It spreads out into a network of branches and lakes in Mali.

Mali has three seasons. Its weather is hot and dry from March to May, warm and rainy from June to October, and relatively cool and dry from November to February. Average annual temperatures are between 80 and 85 °F (27 and 29 °C) in much of the country. From March to July, temperatures often exceed 100 °F (38 °C). In the Sahara, they may rise to more than 110 °F (43 °C) during the day. But at night, Sahara temperatures may be as low as about 40 °F (4 °C).

Rainfall in Mali can vary greatly from year to year, and the country has experienced devastating droughts. The Sahara receives only tiny amounts of rain each year, while the Sahel receives between about 7 and 20 inches (18 and 51 centimeters). Southern Mali averages between about 20 and 60 inches (51 and 152 centimeters).

Animal and plant life.

Many wild animals are found in southern Mali. They include elephants, gazelles and other antelope, giraffes, hyenas, leopards, and lions. Crocodiles and hippopotamuses live in the river areas.

Mali has diverse plant life. Trees scattered throughout the southern grasslands include cailcedra, kapioka, karite, and nere. The Sahel has baobab, down palm, and palmyra trees. It also features acacia, cramcram, mimosa, and other short, thorny plants.

Economy.

Mali faces several economic problems. It is a poor country, and many of its people live in poverty. The country is heavily reliant on foreign aid. Remittances (money sent home) from Malians working abroad is important to the country’s economy.

Mali depends heavily on agriculture, but only a small amount of its land is fertile. Crop production has often suffered from below-normal rainfall. Severe droughts have destroyed crops and killed livestock. In addition, pasture for grazing has become increasingly scarce. Mali’s economy has also been troubled by sharp drops in world cotton prices. Mali’s limited industry and reliance on agriculture hinder economic progress. Malians are working to establish a more balanced economy to lessen the economic disasters caused by droughts and other agricultural problems.

Most of Mali’s workers farm or herd livestock for a living. Corn, millet, rice, and sorghum are the main food crops. Cotton and peanuts are important cash crops. Nomads raise large herds of cattle, goats, and sheep for both meat and milk. Much of the country’s agricultural production occurs near the Niger River. Fishing is also an important economic activity. The largest catches include catfish, perch, and tilapia. The fish come mainly from the Bani and Niger rivers and Lake Debo.

Service industries account for nearly half of Mali’s total economic production. Many people employed in service industries work in Bamako and other urban areas. Hotels, restaurants, and shops are helped by the increasing number of tourists who visit Mali each year. Many of these tourists visit from France, Spain, the United States, and other African countries.

Manufacturing plays a small role in Mali’s economy. The country’s factories produce beverages, cement, clothing, sugar and other food products, and textiles. The government once owned many industrial facilities but has sold many of them to private investors. Most of Mali’s largest industrial plants were built with foreign aid.

Mining is an expanding economic activity in Mali. Gold has become one of the country’s leading exports. The production of salt is another important mining activity. Mali also has deposits of bauxite, copper, iron ore, manganese, phosphates, and uranium.

Mali imports more than it exports. Leading imports include food, machinery, petroleum products, pharmaceuticals (medicinal drugs), and transportation equipment. The country exports cotton, gold, and livestock. Mali’s leading trade partners include China, Côte d’Ivoire, France, Senegal, and South Africa.

Most of the country’s roads are unpaved. The Niger River is navigable throughout its course in Mali. A railroad links Bamako and Dakar, Senegal. Bamako and Gao have international airports.

Mali has several daily newspapers and television stations, and many radio stations. The government publishes one of the newspapers and operates one each of the radio and TV stations. The rest are privately owned.

History.

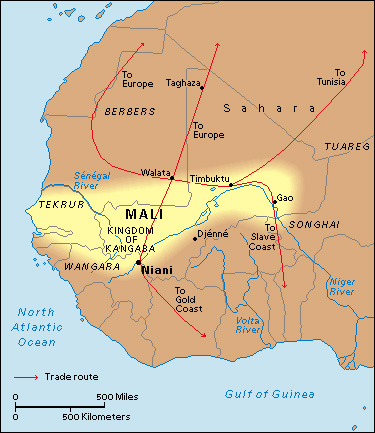

Mali has a rich cultural heritage. From about the A.D. 300’s to the late 1500’s, areas in what is now Mali formed part of one or more of three great African empires. These empires—Ghana, Mali, and Songhai—grew prosperous because they controlled important trade routes.

The Ghana Empire began as early as the 300’s and lasted until the mid-1000’s. It became known as “the land of gold” because traders brought gold there from fields farther south and exchanged it for salt and other goods from North Africa. See Ghana Empire.

The Mali Empire flourished from about 1240 to 1500. In the 1300’s, it ranked as the wealthiest and most powerful state in western Africa. Mansa Musa, its king from 1312 to about 1337, brought Muslim scholars to the empire, and the city of Timbuktu started to become a center of Muslim learning. See Mali Empire; Timbuktu.

The Songhai Empire began in the 700’s. The Malian city of Gao served as its capital. Under Askia Muhammad, who ruled the Songhai Empire from 1493 to 1528, Timbuktu reached its peak as a center of wealth and Muslim learning. Invaders from Morocco overran Songhai in 1591. Many small kingdoms later ruled the area. See Askia Muhammad; Songhai Empire.

During the mid-1800’s, France began attempts to set up a colony in what is now Mali. But French troops met strong resistance from ethnic African groups and did not gain control of the area until 1895. In 1904, the colony, then called French Sudan, became part of French West Africa. In 1946, France gave French Sudan the status of a territory in the French Union. See French West Africa.

In 1958, French Sudan became a self-governing republic within the French Community, an organization that linked France and its overseas territories. The next year, French Sudan and Senegal united to form the Federation of Mali. Modibo Keïta, a Malian leader, became head of the federation. The federation broke up in August 1960. On Sept. 22, 1960, French Sudan gained complete independence as the Republic of Mali.

Keïta became Mali’s first president. He tried to develop the economy, partly by establishing close ties with the Soviet Union and other Communist nations. However, worldwide inflation and an unsuccessful attempt to set up a new money system led Mali into debt.

In 1968, a group of Malian military leaders overthrew Keïta. Moussa Traoré, one of the leaders, took control of Mali’s government as head of a military committee.

In 1974, Malians approved a constitution that called for a gradual transition to an elected president and legislature. The first elections were held in 1979. All the candidates belonged to the Mali People’s Democratic Union. Traoré, who headed the party, was elected president.

In the 1970’s and early 1980’s, severe droughts struck the Sahel and brought widespread famine to Mali. Millions of cattle, goats, and sheep died. Thousands of Fulani and Tuareg herders, who depended on their livestock for meat and milk, died from malnutrition. The United Nations (UN) and a number of countries gave Mali food to prevent mass starvation.

In 1991, Malian government forces killed many people in a crackdown against antigovernment protests. Later that year, military leaders overthrew Traoré and formed a temporary government composed of military and civilian members. In 1992, a new constitution was adopted. It provided for a multiparty system and an elected government. A new civilian president, Alpha Oumar Konaré, was elected. A new National Assembly was also elected.

In 1993, former President Traoré was jailed for his role in the 1991 killing of antigovernment protesters. In 1999, he was also convicted of embezzlement. President Konaré later granted Traoré a full pardon for his crimes.

In 2002, Amadou Toumani Touré became president. Touré had helped lead the overthrow of Traoré in 1991. Touré was reelected in 2007, but in the spring of 2012, a military coup forced him from office. Soon after the coup, Tuareg and Islamist militants rebelled in northern Mali. The military installed a new government with Dioncounda Traoré, president of the National Assembly, as Mali’s interim president.

The rebellion in northern Mali worsened late in 2012. In 2013, French troops and warplanes began helping Malian forces fight the Islamist militants. Thousands of UN peacekeeping troops also arrived to help. Despite the ongoing turmoil, voters elected former prime minister Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta as the nation’s president.

In 2015, the Malian government signed a peace deal with Tuareg rebels, ending the rebellion. The deal did not include Islamist militants, who have since caused increasing violence, particularly in central Mali. In addition, armed local militias have carried out attacks on ethnic minority groups, killing many civilians.

Keïta was reelected president in 2018. However, in August 2020, soldiers overthrew Keïta in a military coup. Keïta resigned and dissolved the parliament. In September, a transitional government was established to lead the government to civilian rule over an 18-month period. The transitional government was itself overthrown in a military coup in May 2021 after disagreements over a Cabinet reshuffle. In June, a new military transitional government was formed. In 2022, France withdrew its military forces from Mali after Mali’s government began working with Russian military contractors.