Mammal is an animal that feeds its young on the mother’s milk. There are more than 4,500 species (kinds) of mammals, and they make up one of the classes of vertebrates (animals with backbones). Many mammals are among the most familiar of all animals. Cats and dogs are mammals. So are such farm animals as cattle, goats, hogs, and horses. Mammals also include such fascinating animals as anteaters, apes, giraffes, hippopotamuses, and kangaroos. And human beings, too, are mammals.

Mammals live almost everywhere. Such mammals as monkeys and elephants dwell in tropical regions. Arctic foxes, polar bears, and many other mammals make their home in polar regions. Such mammals as camels and kangaroo rats live in deserts. Certain others, including seals and whales, swim in the oceans. One group of mammals, the bats, can fly.

The largest animal that has ever lived, the blue whale, is a mammal. It can measure more than 100 feet (30 meters) long and weigh more than 150 tons (135 metric tons). The smallest mammal is the Kitti’s hog-nosed bat of Thailand. It is about the size of a bumble bee and weighs only about 1/14 ounce (2 grams).

Some mammals live a long time. Elephants, for example, live about 60 years, and some human beings reach the age of 100 years or more. On the other hand, many mice and shrews live less than a year.

Mammals differ from all or most other animals in five major ways. (1) Mammals nurse their babies—that is, they feed them on the mother’s milk. No other animals do this. (2) Only mammals have true hair. All mammals have hair at some point in their life, though in certain whales it is present only before birth. Other living things, including bees and some plants, have hairlike coverings on their bodies. But these coverings are not true hair. (3) Mammals are warm-blooded—that is, their body temperature remains about the same all the time, even though the temperature of their surroundings may change. Birds are also warm-blooded, but nearly all other animals are not. (4) Mammals have a larger, more well-developed brain than do other animals. Some mammals, such as chimpanzees, dolphins, and especially human beings, are highly intelligent. (5) Most mammals give their young more protection and training than do other animals. Aside from these five major differences, other unusual characteristics of mammals include a four-chambered heart, a lower jaw with a single bone on each side, and an outer ear.

Several hundred separate World Book articles give details on specific kinds of mammals. Readers can find these articles by consulting the general articles listed in the Related articles with this article.

The importance of mammals

How people use mammals.

Since the earliest times, human beings have hunted other mammals. Prehistoric people ate the flesh of wild mammals, used their skins for clothing, and made tools and ornaments from their bones, teeth, horns, and hoofs.

More than 10,000 years ago, people learned they could domesticate (tame and raise) certain useful mammals. Hunters tamed wolves and from them bred dogs, the first domestic animals, to guard homes and track and bring down game. People later domesticated the wild ancestors of today’s cattle, goats, hogs, and sheep. Since then, these mammals have provided meat, leather, and other products. Horses and oxen have long been used to carry people or their goods. Camels, elephants, goats, llamas, reindeer, and even dogs have also been used for transportation.

Some mammals, especially cats, dogs, hamsters, and rabbits, are popular pets. Certain mammals are used in scientific research. For example, new drugs are tested on domestic mice and rats and on dogs, guinea pigs, monkeys, and rabbits.

Although domestic mammals provide many products, people still hunt wild mammals. They hunt such mammals as antelopes, deer, rabbits, and squirrels for their flesh or hides. Whales are killed for their meat and oil, and seals for their skins. Beavers, muskrats, otters, and other wild mammals that have thick coats are trapped for their fur. Elephants, hippopotamuses, and walruses are killed for their tusks, which consist of ivory. Rhinoceroses are killed for their horns.

Loading the player...Otters

Wild mammals are also a source of enjoyment. Many people travel to national parks to delight in viewing bears, deer, moose, and other mammals in their natural environments. Other people visit zoos, where they can see interesting mammals from many countries. Even in the largest cities, people can still find some wild mammals, such as the gray squirrel and the chipmunk.

Mammals in the balance of nature.

Mammals are important not only to people but also to the whole system of life on Earth. Many mammals help plants grow. For example, animals that eat plants leave seeds in their droppings (body wastes). Many of these seeds sprout into plants. Similarly, many of the nuts that squirrels bury for a food supply grow into trees. Gophers, prairie dogs, and other burrowing mammals dig up the soil. This activity mixes the soil with air, water, and decaying leaves, which promotes the growth of plants.

Flesh-eating mammals also help maintain the balance of nature by feeding on plant-eating animals. If such flesh-eaters as wolves, mongooses, and weasels did not control the number of plant-eaters, certain species of plants in an area could be drastically reduced or even wiped out. Other mammals help keep the insect population under control. For example, aardvarks, giant anteaters, and pangolins eat millions of ants and termites at each meal. Every night, bats eat great numbers of insects. Scavenger mammals, such as coyotes, hyenas, and jackals, clean up the remains of large animals that have been killed or that died naturally.

Even the wastes and dead bodies of mammals are important to the balance of nature. Mammal droppings are a valuable fertilizer. The bones of dead mammals break down into chemicals that are needed by animals and plants. Rodents often chew on mammal bones and antlers that deer have shed because these remains are important sources of calcium and other minerals. For more information, see Balance of nature.

The bodies of mammals

Mammals have many ways of life, and each species has a body adapted to its particular way of life. However, all mammals share some basic body characteristics. These characteristics include certain features of their (1) skin and hair, (2) skeleton, and (3) internal organ systems.

Skin and hair

cover the body of mammals. Skin consists of an inner layer, the dermis, and an outer layer, the epidermis. The dermis contains the arteries and veins that supply the skin with blood. The epidermis, which has no blood vessels, protects the dermis. It also produces special skin structures, including hair, horns, claws, nails, and hoofs.

The skin of mammals has a rich supply of glands. Mammary glands produce the milk that female mammals use to nurse their young. Sebaceous glands give off oil that lubricates the hair and skin. Sweat glands eliminate small amounts of liquid wastes, but their main purpose is to help mammals cool off. As sweat evaporates from the skin, it cools the surface. Many mammals, such as dogs and skunks, also have scent glands. Dogs use their scent glands for communication and identification. Skunks spray a bad-smelling liquid from their scent glands as a means of self-defense.

Many mammals have two types of hairs. The underhair consists of soft, fine hairs that form a thick, warm coat. The outer guard hair consists of longer, slightly stiffened hairs that give shape to a mammal’s coat and protect the underhair. Many mammals have long, stiff hairs about the mouth or other parts of the head. These hairs, called vibrissae or tactile hairs, serve as highly sensitive touch organs. The whiskers of cats and mice are examples of such hairs.

Hair serves many purposes. The hair color of many mammals blends with the animals’ surroundings and so helps them hide from their enemies or prey. Some mammals have specialized guard hairs, such as the quills on a porcupine, that provide protection against enemies. But the main purpose of hair is to keep the animal warm. Dolphins and whales, which lack body hair, have a thick layer of fat that provides warmth. Other mammals with little hair, such as elephants and rhinoceroses, live in warm climates. See Skin; Hair.

Skeleton

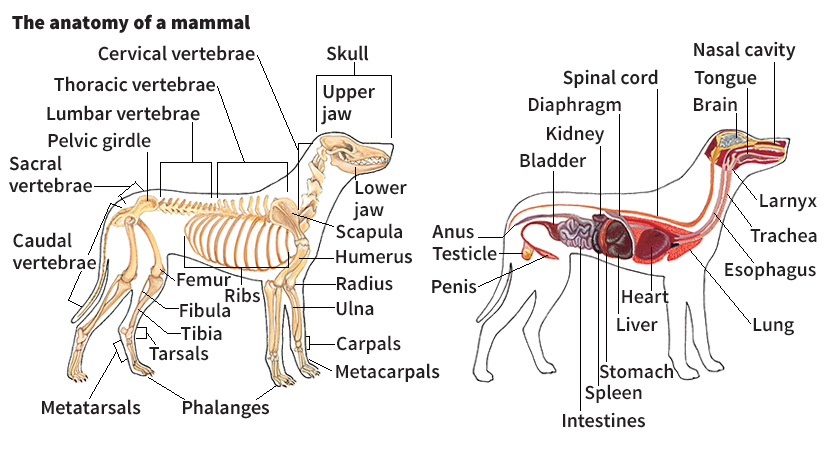

of mammals provides a framework for the body and protects vital organs. In addition, the muscles that enable a mammal to move are attached to the skeleton. The skeleton of all adult mammals—whether blue whales or shrews—consists of more than 200 bones. Some of these bones are fused (united) and so form a single structure. The skeleton has two main parts: (1) the axial skeleton and (2) the appendicular skeleton.

The axial skeleton

consists of three regions. These regions are the skull, the vertebral column, and the thoracic basket.

The skull houses the brain in a bony box called the cranium. The skull also includes the jaws and teeth and areas for the organs of hearing, sight, and smell. Some mammals have bony growths from the skull, such as the antlers on deer.

The vertebral column, or spine, consists of five kinds of vertebrae (spinal bones): (1) cervical, in the neck; (2) thoracic, in the chest; (3) lumbar, in the lower back; (4) sacral, in the hip; and (5) caudal, in the tail. All mammals, except manatees and sloths, have seven cervical vertebrae. The number of each of the other kinds of vertebrae varies with the species of mammal.

The thoracic basket is made up of the ribs, which are attached to the thoracic vertebrae. Most of the ribs also are joined to the breastbone. The thoracic basket forms a bony cage that protects the heart, lungs, and other vital organs.

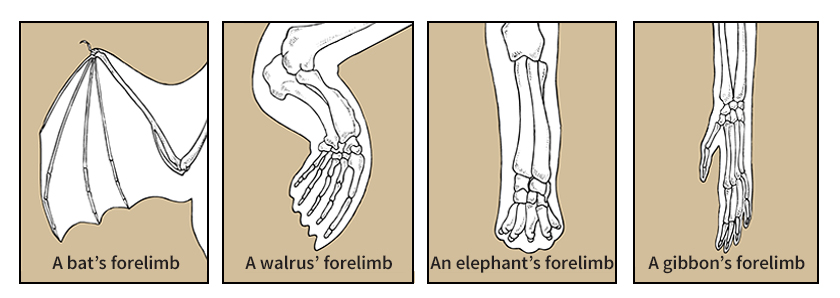

The appendicular skeleton

is made up of the limbs and their supports. The forelimbs are attached to the axial skeleton by the shoulder girdle, which consists of a broad shoulder blade and, in most species, a narrow collarbone. The hindlimbs are attached to the sacral vertebrae by a hip girdle consisting of three bones. In many mammals, the three bones of the hip girdle are fused to one another and to the sacral vertebrae.

A single bone forms the upper portion of each limb. In most mammals, the lower part of each limb has two bones. These bones are fused in some mammals. The wrist, palm, ankle, and sole consist of several small bones. The number of these depends on how many fingers or toes the mammal has. See Skeleton.

Internal organ systems

are groups of organs that serve a particular function. The major systems of mammals include (1) the circulatory system, (2) the digestive system, (3) the nervous system, and (4) the respiratory system.

The circulatory system

consists of the heart and blood vessels. Mammals have an extremely efficient four-chambered heart, which pumps blood to all parts of the body. The blood carries food and oxygen to the body tissues, where they are burned to release energy. The red blood cells of mammals can carry more oxygen than can the cells of all other animals except birds. The circulatory system’s high efficiency is associated with warm-bloodedness. Mammals must burn large amounts of food to maintain a high body temperature. See Blood; Circulatory system; Heart (Birds and mammals).

The digestive system

absorbs nourishing substances from food. It consists basically of a long tube that is formed by the mouth, the esophagus, the stomach, and the intestines. The digestive system of mammals varies according to the kind of food an animal eats. Mammals that eat flesh, which is easy to digest, have a fairly simple stomach and short intestines. Most mammals that eat plants, however, have a complicated stomach and long intestines. For example, cows and sheep have a four-chambered stomach. Each chamber helps break down the coarse grasses that the animals eat. See Digestive system; Ruminant.

The nervous system

regulates most body activities. It consists mainly of the brain and spinal cord and their associated nerves. Most kinds of mammals have a larger brain than do other animals of similar size. In addition, mammalian brains have an extremely well-developed cerebral cortex. This part of the brain serves as the center for learning and gives mammals superior intelligence. See Brain; Nervous system.

The respiratory system

enables mammals to breathe. It is made up of two lungs and various tubes that lead to the nostrils. A muscular sheet called the diaphragm divides the chest cavity from the abdominal cavity and aids in breathing. Only mammals have a muscular diaphragm. In most mammals, the nostrils are at the end of the snout or nose. Dolphins and whales have their nostrils, called blowholes, at the top of the head. Dolphins and some whales have one nostril. Other whales have two. See Lung; Respiration.

Loading the player...Dolphins

Other organ systems

of mammals include the endocrine, excretory, and reproductive systems. The endocrine system consists of glands that produce hormones, substances which help regulate body functions. The excretory system eliminates wastes from the body by means of the kidneys. For information on these two systems, see the articles Hormone and Kidney. For a discussion of the reproductive system, see the section of this article titled How mammals reproduce.

The senses and intelligence of mammals

Senses.

Mammals rely on various senses to inform them of happenings in their environment. The major senses of mammals are (1) smell, (2) taste, (3) hearing, (4) sight, and (5) touch. However, the senses are not equally developed in each species of mammal. In fact, some species do not have all the senses.

Smell

is the most important sense among the majority of mammals. Most species have large nasal cavities lined with nerves that are sensitive to odors. These animals rely heavily on smell to find food and to detect the presence of enemies. In many species, the members communicate with one another through the odors produced by various skin glands and body wastes. For example, a dog urinates on trees and other objects to tell other dogs it has been there. A few species of mammals, especially human beings, apes, and monkeys, have a poorly developed sense of smell. Dolphins and whales seem to lack the sense entirely. See Smell.

Taste

helps mammals identify foods and so decide what foods to eat. This sense is mainly in taste buds on the tongue. However, much of the sense of taste is strongly affected by the odor of food. See Taste.

Hearing

is well developed in most mammals. Most species have an outer ear, which collects sound waves and channels them into the middle and inner ear. Only mammals have an outer ear. See Ear for a description of the human ear, a typical mammalian ear.

Some mammals use their sense of hearing to find food and avoid obstacles in the dark. Many bats, for example, produce short, high-pitched sounds that bounce off surrounding objects. Bats can use these sounds and their echoes to navigate and even to detect tiny flying insects. Dolphins, porpoises, and some whales also use this system, called echolocation, to navigate, find food, and avoid objects underwater. However, most of the sounds they make are pitched much lower than are the sounds of bats. Other echolocating mammals include shrews and some seals.

Sight

is the most important sense among the higher primates (apes, monkeys, and people). The structure and function of the eye is similar in all mammals. However, the eyes of the higher primates have more cones than do those of most other mammals. These structures give apes, monkeys, and people sharp daytime vision and the ability to tell colors apart. A few other mammals that are active during the day have some color vision, but most mammals are color-blind. Many species of mammals that are active at night have large eyes with a reflector at the rear. This reflector, called the tapetum lucidum, helps the animal see in the dark. It produces the eyeshine a person sees when light strikes the eyes of a cat or a deer at night. See Eye.

Touch.

Most mammals have a good sense of touch. Tactile nerves—that is, nerves that respond to touch—are found all over a mammal’s body. But some areas have an especially large number of these nerves and are extremely sensitive to touch. The whiskers of such mammals as cats, dogs, and mice have many tactile nerves at their base. These whiskers help the animals feel their way in the dark. Moles and pocket gophers have a highly sensitive tail, which aids them when backing up in their dark, narrow tunnels. Primates’ fingers have many tactile nerves, as do the paws of raccoons.

Intelligence

is related to the ability to learn. Through learning, an animal stores information in its memory and then later uses this information to act in appropriate ways. Mammals, with their highly developed cerebral cortex, can learn more than other kinds of animals.

Intelligence is difficult to measure, even in human beings. The size of the surface area of the brain, especially of the cerebral cortex, generally indicates an animal’s learning ability. In the more intelligent mammals, such as chimpanzees and dolphins, the cerebral cortex is fairly large and has many folds, which further increase its surface area. Human beings have the most highly developed cerebral cortex.

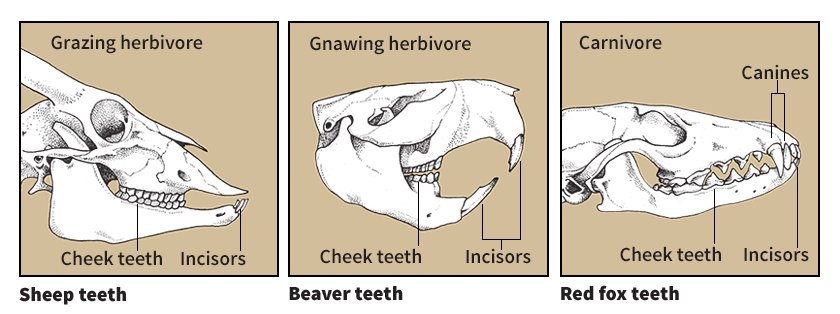

What mammals eat

Most mammals are herbivorous—that is, they eat plants. Plant food is generally tough and so tends to wear teeth down. Herbivorous mammals have special teeth that help counteract such wear. Many plant-eating mammals, including cattle, elephants, and horses, have high-crowned teeth that wear down slowly. The incisors (front teeth) of such mammals as rodents and rabbits grow continuously to keep up with the wear caused by chewing.

Some mammals are carnivorous. They eat animal flesh. Many of them are speedy hunters that catch, hold, and pierce their prey with long, pointed canine teeth. Such mammals, which include leopards, lions, and wolves, do not thoroughly chew their food. They swallow chunks of it whole. Dolphins, seals, and other fish-eating mammals also use their teeth to grasp prey, which they swallow whole. Some carnivorous mammals commonly feed on the remains of dead animals, instead of hunting and killing fresh prey. Hyenas are especially adapted to such a diet and have extremely powerful jaws that can crush even large bones.

Some mammals eat both plants and animals. These omnivorous mammals have teeth that can grind up plants and tear off flesh. They include bears, hogs, opossums, raccoons, and human beings. Some omnivorous mammals change their diet with the seasons. For example, spotted skunks feed mostly on fruits, seeds, and insects in summer. In winter, they eat mainly mice and rats.

How mammals move

On land.

Most mammals live on the ground. The majority of these terrestrial animals move about on four legs. They walk by lifting one foot at a time—first one forefoot, then the opposite hindfoot, next the other forefoot, and then the opposite hindfoot. At faster speeds, most four-legged mammals trot, lifting one forefoot and the opposite hindfoot at the same time. A few species, including camels and giraffes, pace rather than trot. Pacing involves lifting both feet on one side of the body at the same time. At their fastest speed, most terrestrial mammals gallop. While galloping, the animal usually has only one foot on the ground at a time. At some point during the gallop, all four feet are in the air.

Loading the player...Giraffe

Jerboas, kangaroos, and kangaroo rats are terrestrial mammals that move by hopping. These animals have powerful hind legs. They also have a long tail that is used for balance.

In trees.

Many mammals that live in forested areas spend most of their time in the trees. These arboreal animals have a number of special body features that help them move through the trees. Monkeys, for example, can use their hands and feet to grasp tree branches. Many monkeys of Central and South America also have a prehensile (grasping) tail, which they can wrap around branches for support. Other arboreal mammals with a prehensile tail include kinkajous, opossums, and phalangers. Some species of anteaters, pangolins, and Central and South American porcupines also have such a tail. Squirrels and tree shrews have sharp, curved claws that aid them in climbing trees. The claws of tree sloths are so long and curved that the animals cannot walk erect on the ground. These mammals spend most of their life hanging upside down from branches.

Loading the player...Gibbon

In water.

Dolphins, porpoises, manatees, and whales are mammals that live their entire life in water. They have a streamlined body and a powerful tail, which they move up and down to propel themselves through the water. Their forelimbs are paddlelike flippers, used for balance and steering. They have no hindlimbs.

Loading the player...Whale

Many other mammals spend much, but not all, of their time in water. Some of these animals, such as capybaras, hippopotamuses, and walruses, swim by moving their forelimbs and their hindlimbs. Other species use mainly their forelimbs. Such swimmers include platypuses, polar bears, and fur seals and sea lions. Still other mammals use only their hindlimbs to swim. These animals include beavers and hair seals.

In the air.

Bats are the only mammals that can fly. Their wings consist of thin skin stretched over the bones of the forelimbs. Bats fly by beating their wings forward and downward, then upward and backward.

Loading the player...Bats

The so-called flying lemurs, flying phalangers, and flying squirrels cannot actually fly. These mammals have a fold of skin between the forelimb and hindlimb on each side of the body. Instead of flapping these “wings,” the animals stretch them out and glide from tree to tree.

Underground.

Pocket gophers, moles, and certain other mammals spend almost all their life underground. Most of these fossorial mammals have strong claws and powerful forelimbs. Many of them have poor vision, and some are blind. The forelimbs of moles are turned so that the broad palms face out and backward. Strong chest muscles attached to the forelimbs enable moles to “swim” through the soil, much as a person swims when doing the breaststroke.

How mammals reproduce

All mammals reproduce sexually. In sexual reproduction, a sperm (male sex cell) unites with an egg (female sex cell) in a process called fertilization. The fertilized egg develops into a new individual. In all species of mammals, the eggs are fertilized inside the female’s body. Male mammals have a special organ, the penis, which releases sperm into the female during copulation (sexual intercourse).

Mating

occurs among most mammals only when the female is in estrus, also called heat. At this time, the female is sexually receptive and will permit copulation. See Estrous cycle.

The time of the estrous period varies with different species. Among many mammals, especially those that live where the climate is constant the year around, the females may come into heat at any time. Such polyestrous (many-estrous) mammals include elephants and giraffes. Among species that live in regions with distinct seasons, all the females may come into heat at a particular time of year. This breeding season, also called the rutting season, is so timed that the offspring will be born when conditions are best for their survival. Some seasonal breeders have one heat period a year. Such monestrous (one-estrous) species include certain bats, bears, and deer. Other species, such as cottontail rabbits, have several heat periods during their breeding season. These mammals are seasonally polyestrous.

Most smaller mammals are promiscuous in their mating behavior. No lasting bond forms between the mates. They remain together only long enough to copulate. Some other species are polygamous. The males of such species, which include American elks and fur seals, gather a harem (group of females) just before and during the mating season. The male tries to mate with each member of his harem. The association between the male and his harem ends after the breeding season. Among many kinds of mammals, the males and females remain together for some time after mating. However, only a few species of mammals seem to take one mate for life. Zoologists believe that such monogamous species include beavers, wolves, and an antelope called a dik-dik.

Reproduction.

Mammals can be divided into three groups according to the way in which new individuals develop from the fertilized eggs. These groups are (1) placentals, (2) marsupials, and (3) monotremes.

Placentals

give birth to fairly well-developed offspring. The vast majority of mammals are placentals. After fertilization occurs, a placental mammal begins to develop in the uterus, a hollow organ in the mother’s abdomen. Another organ, called the placenta, attaches the developing mammal, called an embryo, to the uterus wall. The embryo receives nourishment from the mother through the placenta.

The time during which the unborn young develops in the uterus is called the gestation period. Among placental mammals, the gestation period ranges from about 16 days in golden hamsters to about 650 days in elephants. Most species with a short gestation period give birth to young that are generally helpless and may be blind and hairless. Most species with a long gestation period bear young that are alert soon after birth. The newborns may also be fully haired, and some can even walk or run almost immediately.

Marsupials

give birth to tiny, poorly developed offspring. Immediately after birth, the young attach themselves to the mother’s nipples. The babies remain attached until they develop more completely. The nipples of most female marsupials are in a pouch, called the marsupium, on the stomach. Marsupials are often known as pouched mammals. However, not all female marsupials have a pouch. Certain kinds of opossums, for example, lack this feature.

There are about 270 species of marsupials. About two-thirds of them live in Australia and on nearby islands. Australian marsupials include kangaroos, koala bears, and wombats. About 70 kinds of opossums, which are marsupials, live in Central and South America. One species lives in the United States and southern Canada.

Monotremes,

unlike all other kinds of mammals, do not give birth to live young. Instead, they lay eggs that have a leathery shell. After an incubation period, the eggs hatch. The only monotremes are the echidnas and the platypus. They live in Australia, New Guinea, and Tasmania.

Care of the young.

All baby mammals feed on milk from their mother’s mammary glands. Baby placentals and marsupials suck the milk from the mother’s nipples. Female monotremes do not have nipples. The milk is released through pores on the mother’s abdomen, and the young lap it up. The nursing period lasts only a few weeks in mice, hares, and many other species. But among some mammals, such as elephants and rhinoceroses, the young may nurse for several years before they are weaned–that is, taken off the mother’s milk. In most species, the young can eat solid food long before they are weaned.

Young mammals must learn many of the skills they need to survive. Much of this learning occurs during the nursing period, when the young are taught how to obtain food and how to avoid dangers. Among most kinds of mammals, the mother alone raises the young. However, the males of some species help care for their offspring. For example, male mice of certain species aid in nest building. Male coyotes and African hunting dogs bring back food for the mother and puppies. Male lions help protect the mother and cubs from attacks by hyenas and other lions.

Among many smaller mammals, such as mice and shrews, the young leave the parental nest or den as soon as they are weaned. But among cheetahs, elephants, wolves, and many other species, the young stay with their parents long after the nursing period ends.

Ways of life

Group life.

Many mammals live in social groups of several individuals. The simplest social group consists of an adult male and female and their offspring. Beavers and certain species of monkeys form such family groups. A larger social group, such as a wolf pack, may have a number of adult and young animals of both sexes. Zebra herds, which consist of an adult male and several females and their young, make up another kind of social group.

Among many social species, the group members are ranked according to a dominance hierarchy. The dominant (controlling) members of the group get first choice of food and mates. They may establish their dominance at first by winning fights. Thereafter, they keep their position mostly by threats. See Dominance.

Group life offers several advantages. Killer whales, lions, wolves, and other predators (hunters) that live in groups cooperate in surrounding and bringing down prey. However, prey species can also profit from group life. If one white-tailed deer senses danger, for example, it can warn the entire herd by flashing the white underside of its tail. Among some prey species, such as baboons and musk oxen, the group assembles into a defensive formation for protection against predators.

Some mammals spend most of their life alone. Such solitary mammals include leopards, tigers, and most other cats except lions. However, even solitary mammals spend some time with members of their species. For example, adult males and females get together to mate, and a mother remains with her young at least until they are weaned.

Solitary mammals have several advantages over social species. They do not have to share available food and shelter. In addition, a solitary predator can hunt its prey more silently than can a group. Among prey species, a solitary animal attracts less attention than a group does, and it can hide more easily.

Territoriality

is a form of behavior in which an animal or group of animals claims and defends a particular area. Other members of the species are kept out of the territory. Many species of mammals establish territories only during the breeding season. For example, a male fur seal claims a territory before mating. He drives all other males from his territory, while he tries to herd as many females as possible into the area. Other mammals, such as gibbons and howlers, claim a territory to help ensure the group of an adequate food supply.

Mammals mark the boundaries of their territories in various ways. For example, hyenas leave solid body wastes and scents produced by special glands to indicate their territorial borders. Wolf packs mark their territories with urine. Such markers serve as “No Trespassing” signs to other members of the species.

Mammals usually defend their territories by threats rather than by actually fighting. A group of howlers, for instance, keeps other howlers out of its territory by shouting at them.

Many mammals are not territorial. But most species, including those that do not claim a territory, have a home range. A mammal wanders over its home range during the daily activities of feeding, drinking, and seeking shelter. Unlike a territory, a home range is not defended against members of the same species. See Territoriality.

Migration.

Some mammals migrate to an area to give birth or to mate. Every fall, for example, gray whales swim from their Arctic feeding waters to the warmer seas off the northwest coast of Mexico. These waters provide little or no food for the whales. The animals make the journey to give birth because newborn whales could not survive in the cold Arctic waters. See Migration.

Hibernation.

Some kinds of mammals hibernate to avoid winter food shortages. During hibernation, an animal goes into torpor, a type of sleep from which it cannot be awakened quickly. The body temperature of a hibernating mammal is lower than normal. In fact, the temperature of most hibernators drops to nearly that of the surrounding air. The heartbeat and breathing slow down greatly. A hibernating mammal does not eat. It lives off the fat in its body. Some hibernating mammals pass in and out of torpor all winter.

Mammals that hibernate include many kinds of bats; echidnas; and chipmunks, woodchucks, and some other rodents. Most of these animals become extremely fat before they go into hibernation. They usually spend the winter in a den or some other protected place where the temperature is not likely to fall below freezing.

Some bears also enter into a sleeplike state during much of the winter. Many scientists believe that a bear’s winter sleep can be classified as hibernation. However, many other scientists do not consider bears to be true hibernators because their body temperature falls only slightly during winter sleep.

A few kinds of mammals estivate—that is, they become inactive during the hottest, driest part of the summer. Estivation is most common in certain kinds of bats, rodents, and other small mammals. See Estivation; Hibernation.

Methods of attack and defense.

Mammals that hunt rely mainly on their sharp teeth to catch and kill prey. Most of these predators also have sharp claws, which they use to grab and hold their victims. Solitary predators generally stalk their prey by slinking and hiding, and many of these hunters have coats that blend with their surroundings. After a predator has sneaked up on its prey, it makes a final dash at high speed to catch the animal before it can escape. Group hunters, such as African hunting dogs and wolves, usually take turns in the chase until they have worn the prey out.

The evolution of mammals

The ancestors of mammals.

Mammals evolved (developed gradually) from a group of tetrapods (four-legged animals) called the amniotes. Amniotes were the first animals to produce eggs with leathery shells that would not dry out on land. The amniotes gave rise to two major groups, called sauropsids and synapsids. Certain sauropsids became the ancestors of reptiles and related animals, and certain synapsids became the ancestors of mammals.

The synapsids arose during the Pennsylvanian Period (about 323 million to 299 million years ago). By the middle of the Permian Period (299 million to 252 million years ago), a branch of the synapsids called the therapsids had appeared. Over tens of millions of years, the therapsids developed many features that would later be associated with mammals. One group of therapsids, the cynodonts, developed especially mammallike teeth, skulls, and limbs. Most scientists believe that the first mammals evolved from the cynodonts.

The first mammals

probably split off from the cynodonts late in the Triassic Period (252 million to 201 million years ago). Numerous fossils from this period might be either early mammals or cynodonts. Scientists cannot be sure because many characteristics of mammals—such as hair, the mammary glands that produce milk, and warm-bloodedness—are not preserved in the fossil record.

By the start of the Jurassic Period (201 million to about 145 million years ago), mammals had definitely evolved. They were tiny, shrewlike animals that probably ate insects and worms. Mammals remained fairly small throughout the Jurassic Period and the Cretaceous Period (about 145 million to 66 million years ago). Dinosaurs ruled the land during these periods. But many primitive groups of mammals developed in Jurassic times. Most scientists believe that one of these early groups led directly to modern monotremes, though the fossil record of egg-laying mammals is extremely incomplete. Many other early groups died out in the Cretaceous Period. But one group, the pantotheres, probably gave rise to marsupials and placentals by the middle of the period.

The Age of Mammals

began with the extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of Cretaceous times. During the Cenozoic Era (66 million years ago to the present), mammals became the dominant land vertebrates. By the end of the Eocene Epoch (56 million to 34 million years ago), all the modern orders (main groups) of mammals had developed. The modern families of mammals appeared during the Oligocene Epoch (34 million to 23 million years ago).

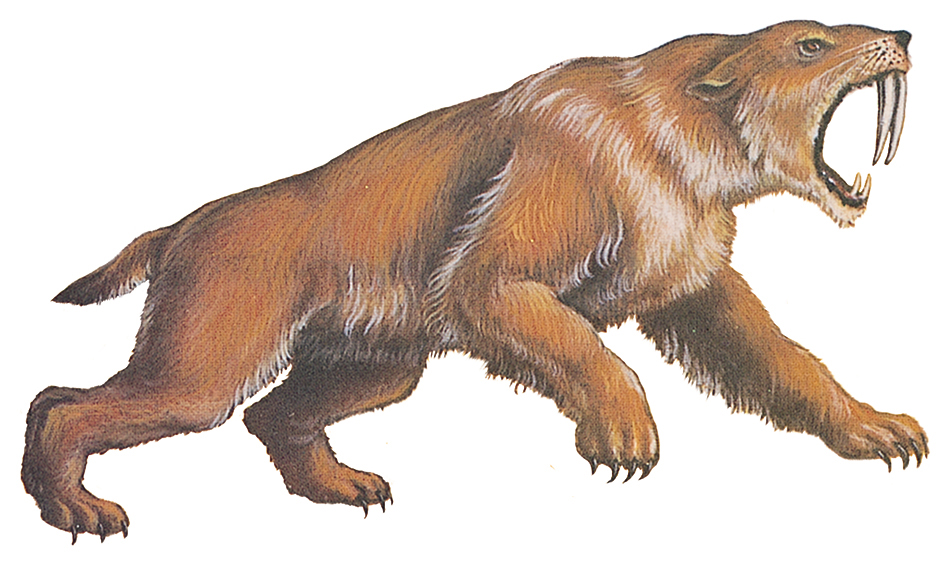

Mammals reached their greatest variety during the Miocene Epoch (23 million to 5.3 million years ago). The number of mammalian species began to decline during the Pliocene Epoch (5.3 million to 2.6 million years ago). The Pleistocene Epoch, which began 2.6 million years ago, brought enormous changes in climate. Several waves of glaciers advanced over much of the land. Many mammals—including ground sloths, mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and woolly rhinoceroses—died out. Most of these extinctions were probably due to the changes in climate. But some might have been caused by a group of new, skillful predators—human beings.

The future of mammals.

Although extinctions are a normal part of evolution, human beings have caused an increasingly rapid decline in the number of wild mammals. Human hunters have exterminated such mammals as the blaubok, also called the bluebuck, of Africa; the zebralike quagga; and Steller’s sea cow. Human beings have also reduced the population of orangutans, rhinoceroses, tigers, and many other mammals to a size so low that these species might not survive in the wild.

Most large wild mammals are now few in number and confined to parks, some of which provide little protection or insufficient living space. Other large mammals are still hunted. Every year, people turn more and more wild lands into farms and towns, and so increasingly deprive mammals of living space. The survival of many wild mammals will depend on the establishment and careful management of large nature preserves and parks.