Miranda, << muh RAN duh, >> v. Arizona was a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States limited the power of police to question suspects. The court ruled in 1966 that nothing arrested persons say can be used against them in their trial unless they have been told they have certain rights. For example, suspects must be told they have the right to remain silent, and that anything they say can be held against them. They also must be told they can have a lawyer present during questioning, and, if they cannot afford one, the court will appoint one. If a suspect requests an attorney, the questioning must cease until an attorney is present.

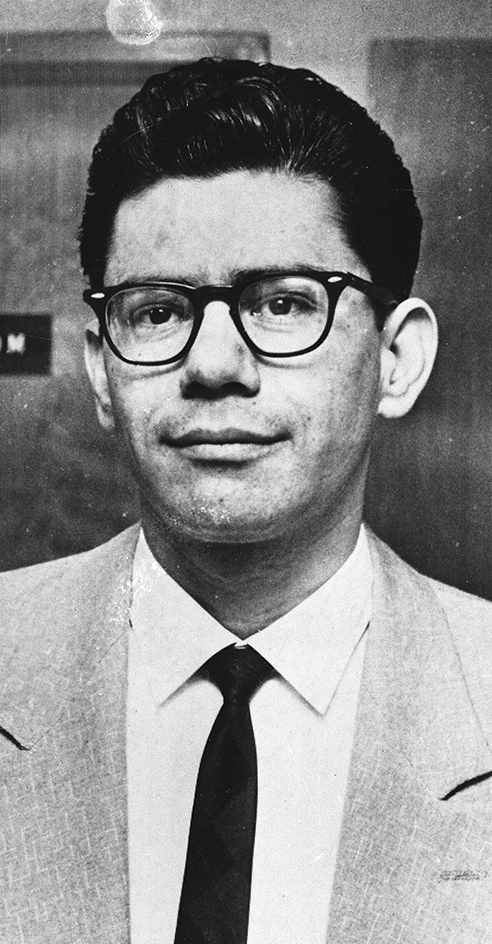

The court’s decision reversed the conviction of Ernesto A. Miranda, a Phoenix warehouse worker, on charges of kidnapping and rape. Miranda had confessed to the charges, and his confession was used as evidence against him. But Miranda had not been told of his right to remain silent and had been denied the right to consult a lawyer.

The Supreme Court based its decision on the Fifth and Sixth amendments to the United States Constitution. The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution protects persons from being forced to testify against themselves. The Sixth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees a defendant’s right to a lawyer.

Several later Supreme Court decisions limited the scope of the ruling in Miranda v. Arizona. In 1971, for example, the court ruled that a confession obtained in violation of the Miranda decision can be used at a trial to prove the defendant is lying. In 2000 and 2004, however, the court upheld the main rulings in the original Miranda decision.

See also Escobedo v. Illinois .