Mission life in America thrived for more than 250 years in a belt of North America known as the Spanish Borderlands. From the 1560’s to the 1820’s, Spanish missionaries established themselves among the region’s Indigenous (native) people, also called Native Americans or Indians. The Borderlands covered a vast area north of Spain’s colonial empire in Latin America. Missions developed in what are now Georgia, Florida, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. French missions arose in the Great Lakes area, and there were some villages of Indigenous converts to Christianity in New England. Christian missions were later established on United States Indian reservations. However, this article focuses on the development, the daily life, and the heritage of the Spanish missions.

In the 50 years after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492, Spain claimed most of North America and South America. The pope, as head of the Roman Catholic Church, granted the Spanish monarchs great authority over the church in the Americas. As a result, missions became agencies of the government. The Spanish government paid the missionaries’ expenses, hoping they could persuade Indigenous people to become loyal Spanish citizens, as well as Roman Catholics. Spain’s two chief interests—the protection of its empire and the conversion of Indigenous people—usually determined where and when missions would be established. Spanish soldiers and missionaries traveled to Florida from Cuba and the Caribbean. Other missionaries in the Spanish Borderlands traveled there by way of New Spain (now Mexico).

Development of the missions

Eastern missions.

In the Roman Catholic Church, missionary work had long been a specialty of certain groups known as orders. Jesuits, members of an order called the Society of Jesus, labored and died among the Indigenous peoples of the humid south Atlantic coast from 1566 to 1572. Most of the missionaries in the Spanish Borderlands, however, were Franciscans, members of the Order of Friars Minor.

Franciscans operated missions in what are now Florida and Georgia for almost 200 years. By 1655, there were 38 missions in the area. Because Indigenous people moved around a great deal to hunt, fish, and wage war, the missions often changed locations. At times, European diseases caused many deaths among the Indigenous people. After the founding of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1670, English settlers began to lure Indigenous people away from the missions with trade goods and guns. Some settlers attacked the Indigenous people, often enslaving or killing them. By 1708, only a few missions were left, and in 1763, Spain surrendered Florida to Great Britain (now part of the United Kingdom).

Western missions.

In 1598, Spain established a colony in the New Mexico area, where the Pueblo people had an advanced civilization. The group that settled there included Franciscan missionaries, who sought to control the colony in the 1600’s. Churches were built in about 50 Pueblo towns. In the early 1600’s, the friars claimed that their missions had about 35,000 inhabitants.

Indigenous groups sometimes challenged European colonization because it disrupted their ways of life. The bloodiest uprising took place in 1680, when the Pueblo drove the outnumbered Spaniards from the New Mexico colony and killed more than 400 of them. The surviving Spaniards retreated to the El Paso, Texas, area. Twelve years later, they recolonized in New Mexico.

In the 1680’s, Spaniards began occupying parts of what is now Texas. Spain relied on missions, presidios (forts), and other settlements to prevent the advance of French explorers and traders into the Texas area. Spain also hoped to befriend the powerful Indigenous groups of this region, including the Apache and Comanche. By the mid-1700’s, there were a few widely scattered clusters of missions that had survived invasions by Indigenous warriors. Some of the most memorable were the adobe and stone missions in the San Antonio area. These missions were known as the “Alamo chain.”

From 1691 to 1711, the Jesuit missionary Eusebio Francisco Kino led many expeditions in the area that is now Arizona. These expeditions created a demand for Spanish missionaries and goods throughout the region. The Franciscans replaced the Jesuits in the Arizona region in 1768. They rebuilt San Xavier del Bac, which Kino had founded near Tucson in 1700. The Franciscans remained in the region until the late 1820’s.

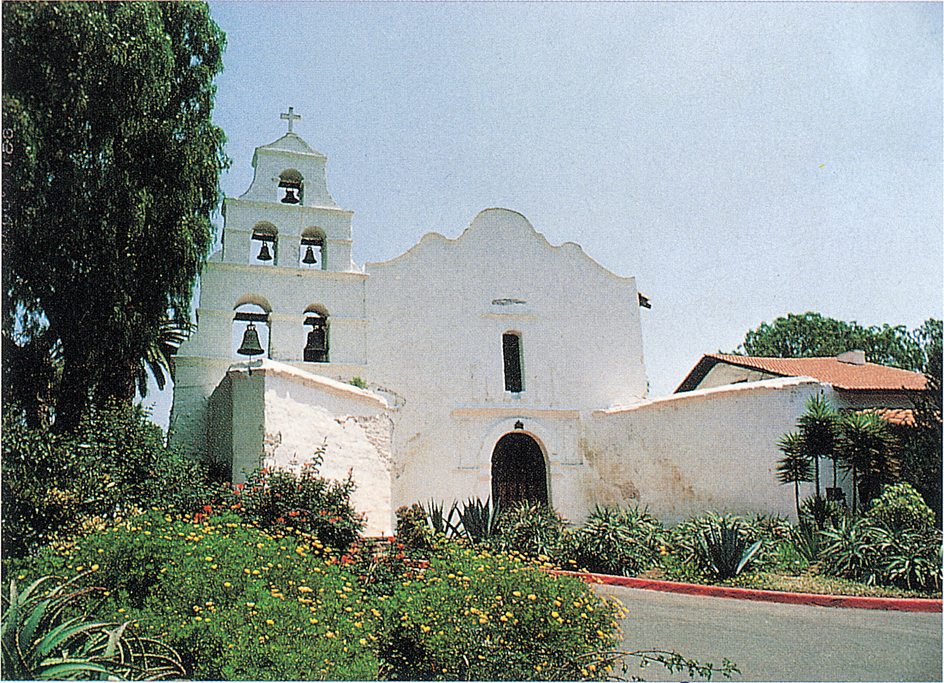

The Spanish settlement of California began in 1769. That year, soldier-settlers and missionaries took possession of the area that became the city of San Diego. The Franciscan missionary Junípero Serra founded the first California mission, known as San Diego de Alcalá, on this site. Serra went on to found 8 more of California’s 21 missions before his death in 1784. These missions became home to thousands of people from dozens of regional Indigenous groups. Some of the California missions developed into major agricultural and manufacturing centers.

From the beginning, Spain intended the mission system in California to be temporary. Missions were a way of securing New Spain’s northern frontiers while preparing the land and local populations for Spanish settlement. Missions were meant to establish pueblos (towns) and to develop agriculture and trade. An additional task was to convert Indigenous people to Christianity.

Under the Spanish, California was owned by a number of families and the Catholic Church. In 1821, California became part of newly independent Mexico. On Aug. 17, 1833, the Mexican Congress passed the Secularization Act, which made the church’s property available to private citizens, effectively ending the mission era.

Life at the missions

The Spanish missions fed, clothed, and often housed the Indigenous people who entered them. In return, the Indigenous people agreed to take instruction in Christianity, to observe Spanish customs, and to work for the mission.

Many Spanish missions included dining areas, schools, storerooms, and workshops, as well as living quarters and a church. In most cases, these structures were built of adobe or stone and arranged around a square courtyard. All the missions had farms, and many operated ranches. The California missions became especially productive. In 1834, Indigenous residents there herded a total of 396,000 cattle; 62,000 horses; and 321,000 sheep, goats, and pigs. They also harvested 123,000 bushels of grain.

In the mornings, Indigenous residents of missions attended religious services and received instruction in Catholicism. Some of them learned to read and write in Spanish. During the rest of the day, they worked, usually on the farms. Some Indigenous residents learned carpentry, metalworking, and other skills from the missionaries and from outside workers hired to supervise construction of the churches and other mission buildings.

At first, many Indigenous people welcomed the benefits of a more reliable and varied food supply, protection from enemies, and the rich ceremonies of Roman Catholicism. Later, various problems developed. Many Indigenous people objected to the highly structured mission routine and to the fact that they were forbidden to leave without permission. They resented the missionaries’ attacks on their former religions and traditions, and they feared the diseases that killed many of their family members. Some Indigenous people fled the missions. Others rebelled, often destroying churches and killing missionaries.

Missionaries were able to keep many Indigenous families under mission discipline for several generations. When the missionaries left or the missions closed, however, some Indigenous people returned to their former way of life. Discrimination and a lack of education prevented even skilled Indigenous workers from getting good jobs and receiving equal rights among white people.

A visitor’s guide

A number of Spanish missions have been maintained through the years, restored, or rebuilt. Following are brief descriptions of some of these Spanish missions.

La Purísima Concepción,

near Lompoc, California, is a state historic park. It was founded in 1787.

Nombre de Díos,

in St. Augustine, Florida, is the oldest U.S. mission. Its first Mass was celebrated in 1565.

Nuestra Señora del Monte Carmelo,

near El Paso, was founded by Franciscans in 1682 as a refuge from the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

San Antonio de Valero,

in San Antonio, is better known as the Alamo. It was the site of a famous battle in 1836, during the Texas Revolution.

San Esteban Rey de Acoma,

at Acoma, New Mexico, was constructed during the 1630’s. It is one of the few churches that survived the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. It stands atop an isolated mesa (tableland) 365 feet (111 meters) high.

San José,

in San Antonio, is part of San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. It was founded in 1720 by the Franciscan Antonio Margil de Jesús.

San Juan Capistrano,

in San Juan Capistrano, California, was established by the Franciscan missionary Junípero Serra in 1776. An earthquake destroyed most of it in 1812.

San Xavier del Bac,

near Tucson, Arizona, still serves local Tohono O’odham (also known as Papago) people. The Jesuit Eusebio Francisco Kino first visited the site in 1692 and founded a mission there in 1700.

Santa Barbara,

in Santa Barbara, California, has been called Queen of the California Missions because of its architectural beauty. Today, it is a Franciscan parish.