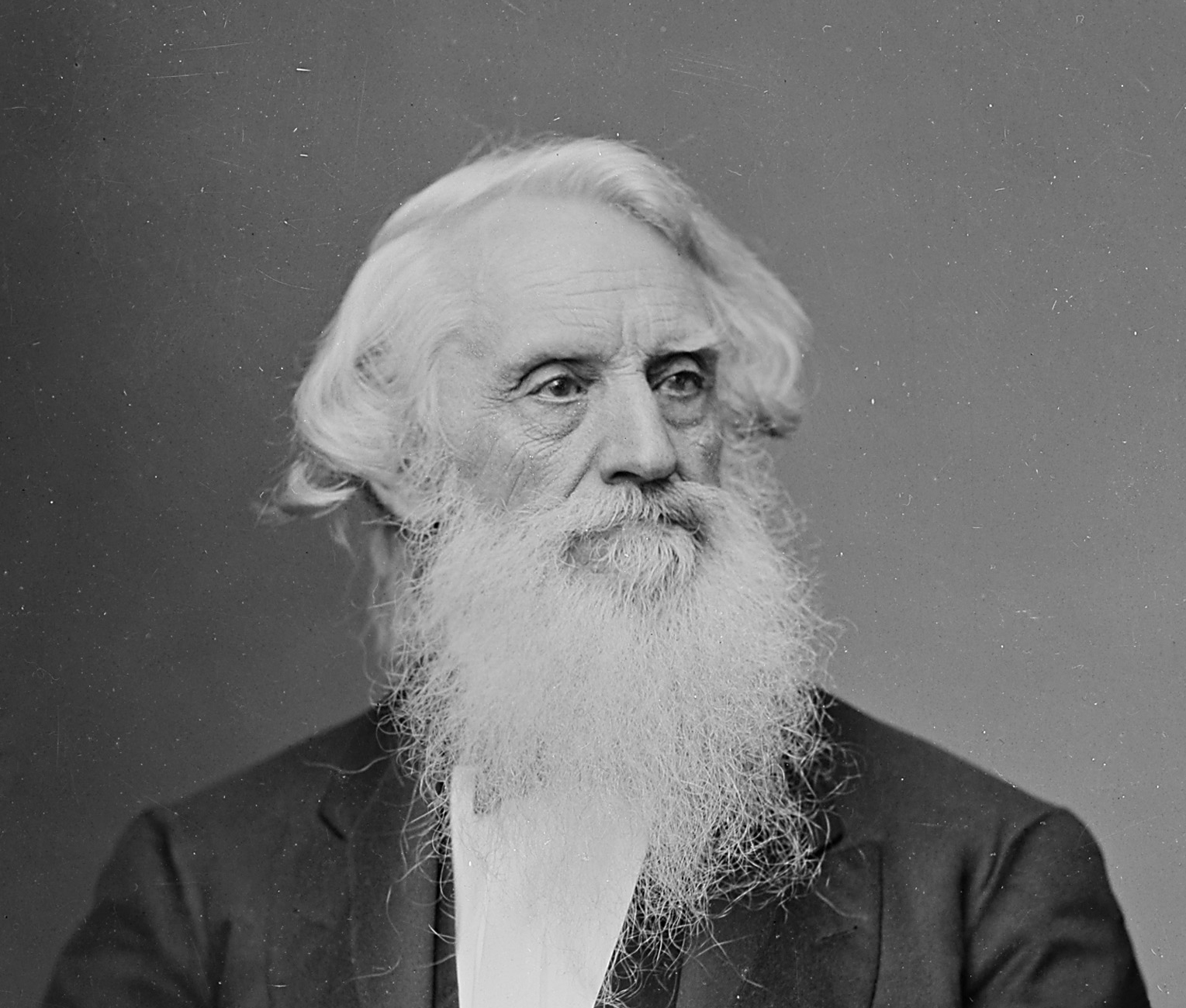

Morse, Samuel Finley Breese (1791-1872), was a famous American inventor and painter. He received the patent for the first successful electric telegraph in the United States. He also invented the Morse code, used for many years to send telegraphic messages (see Morse code ). Morse helped found the National Academy of Design and served as its first president.

Early years.

Morse was born on April 27, 1791, in Charlestown, Massachusetts. His family was devoutly Calvinist, and its conservative religious beliefs influenced Morse throughout his life.

Morse attended Yale University. While there, he studied chemistry with Benjamin Silliman and natural philosophy with Benjamin Day. Both men also lectured on the new science of electricity. From Silliman, Morse learned about batteries and constructed several of his own. However, Morse was an indifferent student. His real passion was art.

Morse graduated from Yale in 1810. The following year, he obtained reluctant permission from his parents to study art abroad. He studied in London with two American-born masters—Washington Allston and Benjamin West. He also studied at the Royal Academy of Arts, where he learned the “Grand Style” of art, which featured themes from history and mythology. In 1813, his first and only sculpture, a figure of the dying Hercules, won critical acclaim and a gold medal in the Adelphi Society of Arts competition. In 1815, having spent all the funds his parents could spare, Morse regretfully returned home.

Morse as artist.

Back in the United States, Morse was unable to secure an income from the historical painting he regarded as his true calling. To earn money, he began painting portraits of members of fashionable society. He considered such painting to be inferior to true art, but he became successful at it. Among his famous subjects were President James Monroe, the poet William Cullen Bryant, and the inventor Eli Whitney. Morse’s portrait of the French soldier and statesman Marquis de Lafayette became his best known painting.

Despite his success as a portrait painter, Morse continued to struggle financially. In 1822, he finished work on a painting that depicted the House of Representatives in session with recognizable portraits of more than 80 members. He planned to charge admission for viewing it, but the public was largely indifferent. Several years later, Morse made another attempt with an elaborate painting of the interior of the Louvre museum in Paris. But this scheme met with the same disappointing result.

In 1826, Morse and 30 other American artists founded the National Academy of Design. Morse was chosen president, an office he held continuously until 1845.

From 1829 to 1832, Morse traveled in Europe, perfecting his artistic technique. In 1832, he was appointed professor of painting and sculpture at the University of the City of New York (now New York University). He later became professor of the literature of the arts of design there. About this time, Morse began his involvement in the nativist movement. This movement regarded immigration and Roman Catholicism as threats against an authentic American republic. Morse wrote a number of passionate articles supporting these positions. In 1836, he ran for mayor of New York City on the Native American ticket but lost the election.

In the mid-1830’s, Morse was denied an important commission he had hoped to obtain to paint historical murals for the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, D.C. Frustrated once again in his dream of devoting himself to art, Morse shifted his attention to the telegraph. After 1837, he did not paint again.

Morse as inventor.

Morse diligently pursued a number of schemes in an effort to acquire an independent livelihood that would enable him to support himself as a serious artist. Among these projects were the invention of a pump for fire engines and a marble-cutting machine to reproduce statues mechanically. The most successful of these efforts, however, was the telegraph.

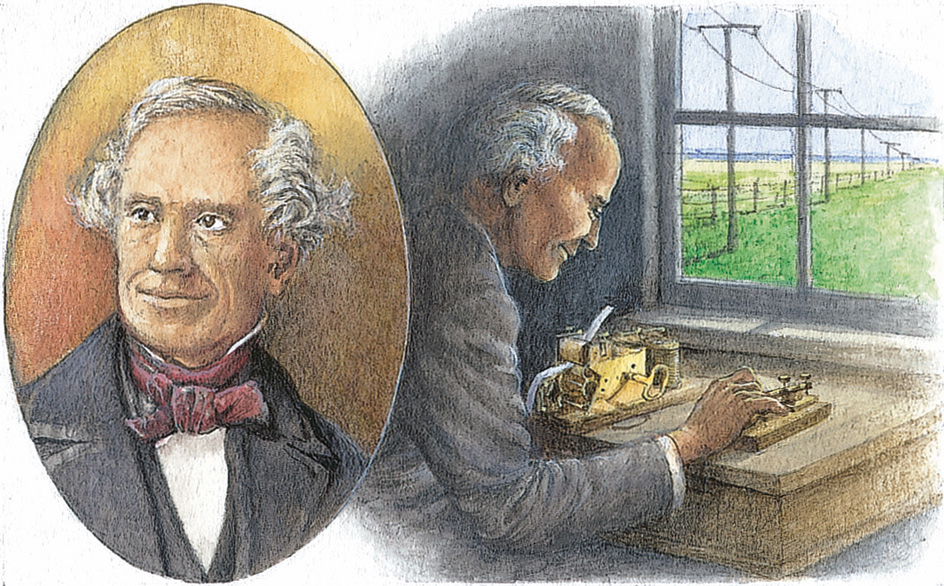

Morse had been interested in electricity since his student days at Yale. In 1827, for example, he attended a series of lectures on electricity given at Columbia University by the American chemist James Freeman Dana. Then, during his return voyage from Europe aboard the ship Sully in 1832, Morse discussed with several other passengers the possibility of communicating at a distance by electricity. He theorized in his diary that transmission could be based on a single circuit using underground wires. He also improvised possible codes.

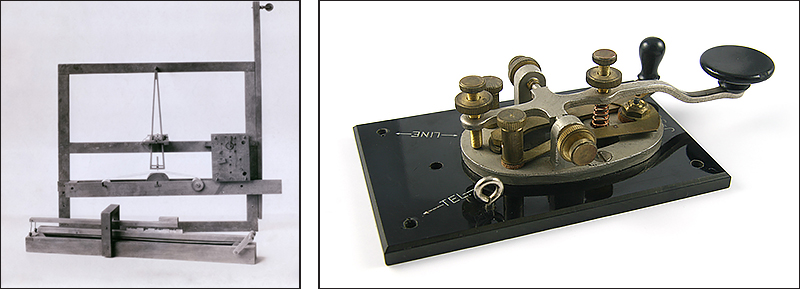

Work on the telegraph went slowly. As a university professor, Morse had little time or money to devote to the telegraph. Using art equipment and parts from old clocks, he finally produced a crude telegraph instrument by early 1846. But this instrument could not send a telegraph signal farther than 40 feet (121 meters).

Morse lacked the scientific background and technical skills to perfect the telegraph on his own. In early 1836, he began to work jointly on the telegraph with Leonard Gale, who taught chemistry at the University of the City of New York. Gale alerted Morse to the work of Joseph Henry, a physicist at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), who had developed electromagnets suitable for use in long-distance signaling. By the end of 1837, Morse and Gale had built an electromagnetic telegraph based on Henry’s work. This device could send messages 10 miles (16 kilometers) on wire strung around Morse’s workroom.

Another key collaborator on the project was Alfred Vail, a skilled mechanic with access to a machine shop. He had approached Morse and offered him funds and assistance. Morse promptly made him a partner.

In 1837, Congress sought proposals for a telegraph system to connect New York City and New Orleans. Only Morse proposed an electric system, but Congress would not advance funds for a small experimental line. In 1840, Morse received a U.S. patent for his telegraph. In its 1841-1842 session, Congress once more failed to act on Morse’s telegraph bill.

Finally, in 1843, Congress granted Morse $30,000 to build a test line between Baltimore and Washington, D.C. On May 24, 1844, Morse formally opened the line by tapping out the famous message, “What hath God wrought!” Morse earned national praise for his device, but, though he wished it, the government did not buy his patents or sponsor a national telegraph.

Over the next decade, Morse and his business associates established a national telegraph network. During the same period, Morse became entangled in several bitter business and legal disputes. One of the most serious disputes pitted Morse against Joseph Henry. In order to protect his patent rights, Morse refused to acknowledge Henry’s key theoretical contributions. In 1859, with his telegraph patent soon to expire, an exhausted Morse retired from the industry he had created.

Later life.

After gaining recognition at home and abroad for developing the telegraph, Morse focused his attention on politics. He continued his support of the nativist movement. He was also an ardent antiabolitionist, believing that slavery had been ordained by the Bible. He was active in the Democratic Party. He ran for Congress in 1854 but lost the election.

By the 1860’s, Morse had finally achieved a degree of financial security. He became a vice president of the new Metropolitan Museum of Art and a trustee of Vassar College. He also made donations to Yale and to various religious and moral societies. In 1871, the telegraph industry honored him with a statue in Central Park in New York City. Morse died on April 2, 1872.

See also Telegraph .