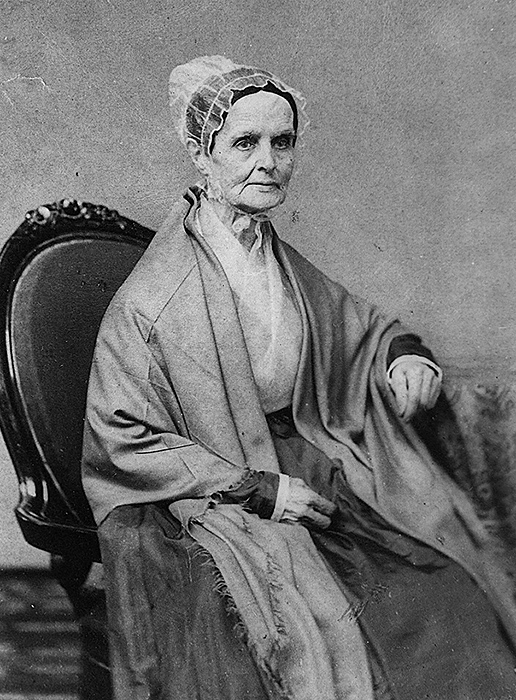

Mott, Lucretia, << loo KREE shuh, >> Coffin (1793-1880), was a leader of the abolitionist and women’s rights movements in the United States. Mott helped establish two antislavery groups, and she and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, another reformer, organized the nation’s first women’s rights meeting.

Mott was born on Jan. 3, 1793, in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Her family were Quakers, and she taught at a Quaker school near Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1808 and 1809. She moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1809. Mott became a Quaker minister in 1821 and, like many other Quakers, was active in the abolitionist movement. She became known for her eloquent speeches against slavery. In 1833, Mott helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She helped organize the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women in 1837.

In 1840, Mott went to London as a delegate to the World Anti-Slavery Convention. However, the men who controlled the meeting refused to seat her and the other women delegates. Mott met Stanton, who was attending the meeting with her husband. The two women were angered by the convention’s action and pledged to work for women’s rights.

In 1848, Mott and Stanton called a women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, where the Stantons lived. The men and women at this meeting passed a Declaration of Sentiments. This series of resolutions demanded more rights for women, including better educational and job opportunities and the right to vote.

After 1848, Mott began to speak widely for both abolition and women’s rights. She also wrote a book, Discourse on Woman (1850). It discussed the economic, educational, and political restrictions on women in the United States and other Western nations. After slavery was abolished in the United States in 1865, Mott supported the movement to give blacks the right to vote. In 1864, she and other Quakers had founded Swarthmore College. Mott died on Nov. 11, 1880.