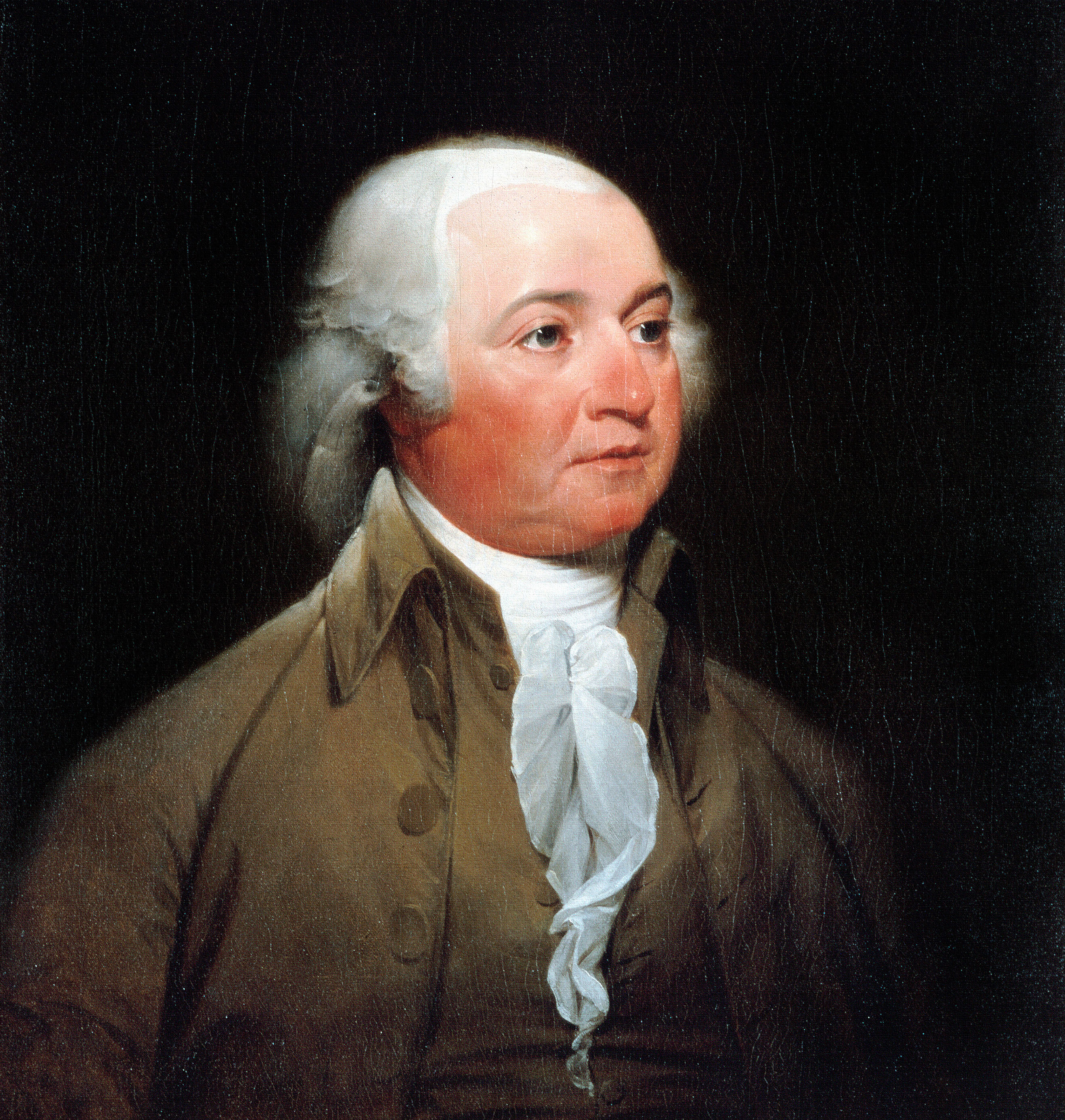

Adams, John (1735-1826), guided the young United States through some of its most serious troubles. He served under George Washington as the first vice president, and followed him as the second president. The United States government moved from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., during Adams’s administration, and he became the first president to live in the White House. Adams was the first chief executive whose son also served as president.

Adams played a leading role in the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, and was a signer of the historic document. He had spoken out boldly for separation from Great Britain (now called the United Kingdom) at a time when most colonial leaders still hoped to settle their differences with the British. As president, Adams fought a split in his own party over his determination to avoid war with France. He kept the peace, but in the process he lost a second term as president. Adams was succeeded by Thomas Jefferson.

In appearance, Adams was short and stout, with a ruddy complexion. He seldom achieved popularity during his long political career. Those close to him loved him, but his bluntness, impatience, and vanity made more enemies than friends. On most great decisions of his public career, history has proved him right and his opponents wrong. But his clumsiness in human relations often caused him to be misunderstood. Few people knew about another part of Adams’s personality. His diary and personal letters show his pleasant, affectionate, and often playful nature.

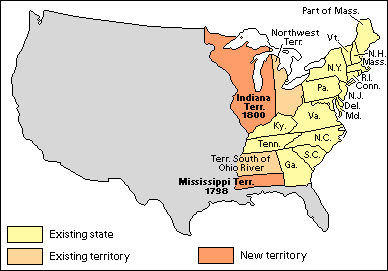

During Adams’s term, the United States took its first steps toward industrialization. The first woolen mills began operating in Massachusetts, and Congress established the Department of the Navy and the Marine Corps. Americans enjoyed such songs as “The Wearing of the Green” and “The Blue Bells of Scotland.” People read and admired The Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington by Mason Locke Weems. On the frontier, Johnny Appleseed began wandering through Ohio and Indiana, planting apple seeds and teaching the Bible.

Early life

Childhood.

John Adams was born in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts, on Oct. 30, 1735. (The date was October 19 by the calendar then in use.) His father, also named John Adams, was a farmer, a deacon of the First Parish of Braintree, and a militia officer. His mother, Susanna Boylston Adams, came from a leading family of Brookline and Boston merchants and physicians.

The Adams farm lay at the foot of Penn’s Hill. The National Park Service preserves as a memorial the house in which John Adams was born. It stands close to the place where his great-great-grandfather, Henry Adams, settled before 1640. Henry Adams had sailed from Somerset, England, along with thousands of other Puritans, to escape the religious persecution found in his homeland.

Young John helped with the chores on the farm. He studied hard in the village school, but did not particularly enjoy books.

Education.

Adams graduated from Harvard College in 1755, ranking 14th in a class of 24. In those days, the rank of a student indicated social position, not scholarship, and Adams was one of the best scholars in his class.

After teaching school for a short time, Adams studied law in the office of James Putnam in Worcester, Massachusetts. He began to practice law in Braintree in 1758. He became a leading attorney of the Massachusetts colony.

Adams’s family.

In 1764, Adams married Abigail Smith (Nov. 22, 1744-Oct. 28, 1818), the daughter of a minister in Weymouth, Massachusetts. (Her birth date was November 11 by the calendar then in use.)

Like most women of her time, Abigail Adams had received little formal schooling. But she read widely, and became one of the best-informed women of the day. She wrote delightful letters to Adams during his absences from home. Mrs. Adams was a lively observer of people and events, and her letters provide colorful pictures of colonial life.

The Adamses’ eldest child, Abigail, became the wife of Colonel William Stephens Smith, the secretary to the United States legation in London. The Adamses’ eldest son, John Quincy, became the sixth president of the United States the year before his father died. The third child, Susanna, died in infancy. The fourth child, Charles, died while his father was president. Thomas, the youngest child, became a lawyer and a judge.

Political and public career

In New England.

Adams took a leading part in opposing British colonial policies in America. The year 1765, when the British Parliament passed the Stamp Act, was a turning point in his life. This law taxed newspapers, legal papers, and other items. It hit Adams hard as a lawyer. He wrote: “This tax was set on foot for my ruin as well as that of Americans in general.”

Adams wrote resolutions against the tax which were adopted by the Braintree town meeting. More than 40 other Massachusetts towns adopted these resolutions. The Boston town meeting appointed Adams to a committee to present a petition against the tax to the British governor. Adams argued that the tax was illegal because the people had not consented to it. This amounted to saying that Parliament could not tax the colonies at all. Britain repealed the Stamp Act in 1766. See Stamp Act.

Adams rejoiced at every expression of popular opposition to the British. But the treatment of British soldiers who had taken part in the Boston Massacre distressed him (see Boston Massacre ). His sense of justice led him to defend Captain Thomas Preston and the British soldiers charged with manslaughter. He felt that the soldiers should be freed, because the mob had provoked them to fire. Adams feared his viewpoint would cost him popularity. Instead, his prestige rose. In 1770, the people of Boston chose him as one of their representatives in the colonial legislature. There, with the help of his cousin, Samuel Adams, he led the fight against British colonial policies.

The British tax on tea enraged Adams and most of his fellow colonists. When a band of patriots dumped large quantities of tea into Boston Harbor on Dec. 16, 1773, Adams called this act “the most magnificent movement of all.” See Boston Tea Party.

National politics.

In 1774, in response to the Tea Party, the British government passed several laws that became known as the Intolerable Acts (see Intolerable Acts ). Under these laws, the British shut down the port of Boston and suspended the Massachusetts government. Massachusetts called for representatives from each colony to meet in Philadelphia. Adams was one of the four Massachusetts delegates at this meeting, later called the First Continental Congress. He and a few other men wanted to seek independence from Britain, but he knew it was too early to propose such drastic action.

Adams’s influence had grown by the time the Second Continental Congress met in 1775. By this time, war had begun, and Adams argued forcefully that the colonies should be independent. He persuaded Congress to organize the 16,000 militiamen of New England as the Continental Army. He also helped bring about the appointment of George Washington as commander in chief.

Beginning in 1776, Adams served as chairman of the Continental Board of War and Ordnance. He also worked on a committee appointed to draft a plan for treaties with European powers, especially with France. Adams later wrote: “I was incessantly employed through the whole fall, winter, and spring of 1775 and 1776, in Congress during their sittings, and on committees in the mornings and evenings, and unquestionably did more business than any other member of the house.”

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a resolution to Congress declaring that “these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States.” Adams seconded the resolution. Congress chose him to be a member of the committee to prepare a declaration of independence. Adams urged Thomas Jefferson to draft the document. Adams defended the Declaration in the stormy debate that followed in Congress.

Diplomat.

Early in 1778, Congress sent Adams to Paris to help Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee strengthen American ties with France and other European nations. Adams arrived in Paris to find that treaties had already been signed with France. He noted that friction had developed among the American ministers, and wrote to Congress proposing that one person take charge of affairs in France. Congress chose Franklin, and Adams sailed home in 1779.

Upon his return to Massachusetts, the people of Braintree elected Adams to the convention that framed a state constitution. Adams wrote almost all the constitution, which had a detailed bill of rights. The document also included a separation of powers that divided the government into three branches—the governor, the legislature, and the courts. In such a system, each branch can use its powers to check and balance (exercise control over) the other two. It would be a “government of laws, and not of men,” Adams wrote. Many other states, and later, the United States, adopted features of this Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. It is the oldest still-functioning written constitution in the world.

During the Massachusetts constitutional convention, Congress appointed Adams to negotiate treaties of peace and trade with Great Britain. He sailed for Paris, and arrived in February 1780. But the British were not prepared to negotiate. Adams then went to the Netherlands to seek diplomatic and commercial support for the American war effort. After two years of hard work, he obtained recognition of the United States as a sovereign (independent) power. He also obtained a loan of about $1,400,000 for the United States. Adams’s mission to the Netherlands ranks among his greatest diplomatic achievements.

In the fall of 1782, Adams joined John Jay and Benjamin Franklin in Paris to meet British and French representatives and arrange a peace treaty. Adams and Jay distrusted the French foreign minister, Count de Vergennes. They feared he would sacrifice American interests to gain advantages for France and its ally, Spain. As a result, the Americans departed from their instructions and negotiated with the British without informing Vergennes of each step taken. Franklin smoothed over affairs with France after the British and Americans had agreed on peace terms.

British and American commissioners signed a preliminary peace treaty on Nov. 30, 1782. The document was signed again in Paris on Sept. 3, 1783, as the final peace treaty. Adams made sure that the United States kept fishing rights in North Atlantic waters. He also arranged provisions recommending amnesty (a general pardon) for Americans who had remained loyal to the British. During the next two years, Adams negotiated another Dutch loan and served in Paris on a commission to negotiate trade treaties with many European governments. He was proud when the French called him “the Washington of negotiations.”

In 1785, Congress named Adams the first U.S. minister to Great Britain. He hoped to negotiate treaties that would encourage trade with Britain. But the British treated Adams coolly, and they made it clear that they would not relax their harsh trade policies. Adams eventually asked to be recalled, and returned home in 1788 after almost 10 years abroad.

Vice president.

Adams had been home only a few months when he was elected vice president. At that time, every elector voted for two men for the presidency. The man who ran second became vice president. Each of the 69 electors voted for George Washington, and 34 gave their second vote to Adams.

Adams later wrote that the vice presidency was “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” Washington relied on others for policy advice, and Adams was left to a vice president’s duties—presiding over Senate debates in which he could not participate. Adams proposed giving the president what he thought was a more suitable title—”His High Mightiness, the President of the United States and Defender of their Liberties”—which earned him ridicule and raised suspicions that Adams favored a monarchy.

The French Revolution, which lasted from 1789 to 1799, divided Americans. Many saw the French pursuit of liberty, equality, and fraternity as an extension of the American Revolution. Others feared the overthrow of established order and the anarchy (lawlessness) that might result. In reaction to the events in France, Adams wrote a series of newspaper articles called Discourses on Davila. Many readers thought these articles indicated that he had become much more conservative in his political views. Old friends, such as Thomas Jefferson, felt he had become too fond of kingly rule and too distrustful of popular government.

Washington and Adams were reelected to second terms as president and vice president, returning to office in 1793. Two political groups began to form in response to the French Revolution, and to Washington’s policies. Adams and Alexander Hamilton led a group that favored a strong federal government. This group, known as the Federalists, supported Washington’s policies. James Madison and Thomas Jefferson led the Democratic-Republicans (called Republicans at the time, though later to become the Democratic Party) in fighting for strong states’ rights. Jefferson resigned as secretary of state in 1793 because he disapproved of the growing dominance of Hamilton in the Cabinet.

By the time Washington refused in 1796 to seek a third term, the two parties had become well defined. The Federalists supported Adams for the presidency, and the Democratic-Republicans nominated Jefferson. Adams received only three more votes than Jefferson did, and the two rivals thus became president and vice president.

Adams’s administration (1797-1801)

The Federalist split.

During Adams’s four years as president, the government faced many problems at home. Relations with European nations were also unsettled. To make his task more difficult, Adams could not count on the support of his party or his Cabinet. Disagreement over foreign policy split the Federalist Party into two groups. Adams led the more moderate of these groups. The other was led by Alexander Hamilton, who had left the Cabinet and returned to private life before Adams became president.

Difficulties with France.

The French Revolution caused most of the problems that faced Adams. President Washington had insisted that neutrality was the best policy in case of a war in Europe. But, in the wars following the French Revolution, European warships attacked American ships. France and Great Britain claimed the right to seize American vessels. The United States was forced to protect itself, and the government launched several new warships, including the Constitution (“Old Ironsides”).

The United States also became involved in the European wars on philosophical grounds. Jefferson believed that the French Revolution was a people’s movement, like the American Revolution. His party sympathized with the French people, and wanted to aid them. But Hamilton led many Federalists in demanding a war against France. Adams was determined to keep the United States neutral, and deplored the policy of Hamilton and his followers. The split in the Federalist Party became irreparable.

One of Adams’s first acts as president was to call a special session of Congress to consider ways of keeping peace. He sent ministers to France to work out a treaty. Three French diplomats offered to negotiate a pact if the United States would bribe Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, the French foreign minister. This episode became known as the XYZ Affair, because the French diplomats were referred to by these initials instead of their names (see XYZ Affair ). The Americans ended the negotiations late in 1797.

The XYZ Affair caused great anger in the United States. People rallied to the cry of “Millions for defense, but not one cent for tribute!” Congress began preparing for war with France. It established the Department of the Navy, ordered the construction of more warships, and summoned George Washington to command the Army. Neither nation declared war, but American and French ships fought many battles.

The Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Federalists faced bitter criticism because of their opposition to France. Most of the criticism came from American citizens, but some of the critics were French. In 1798, the Federalists passed laws designed to limit this criticism. Two Alien Acts gave the president authority to banish or imprison foreigners. The Sedition Act made it a crime to criticize the government, the president, or Congress. Adams never used the Alien Acts, but a number of journalists who supported Jefferson were arrested for violation of the Sedition Act. See Alien and Sedition Acts.

These laws caused a storm of disapproval. Many people claimed they violated the guarantees of freedom of speech and of the press. Jefferson wrote the resolutions adopted by the Kentucky legislature declaring the Alien and Sedition Acts unconstitutional (see Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions ). Historians agree that the acts were unwise.

Adams and peace.

Adams was still determined to keep peace. He again asked Talleyrand for a treaty. This time, Talleyrand was eager to negotiate, because he feared that the United States might join forces with Great Britain. Without consulting Congress, Adams sent a second commission to France. This act was the boldest of his career as president, and it lost him support in his own party. But he believed that avoiding war was the most important achievement of his administration.

Election of 1800.

Hamilton strongly criticized Adams for not fighting France. This argument influenced many Federalist voters. The Democratic-Republicans denounced Adams for the Alien and Sedition Acts, and for hostility toward France. The Democratic-Republican presidential candidates, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, received 73 electoral votes each. Adams received 65 electoral votes. Because Jefferson and Burr had tied, the House of Representatives chose the president. It selected Jefferson.

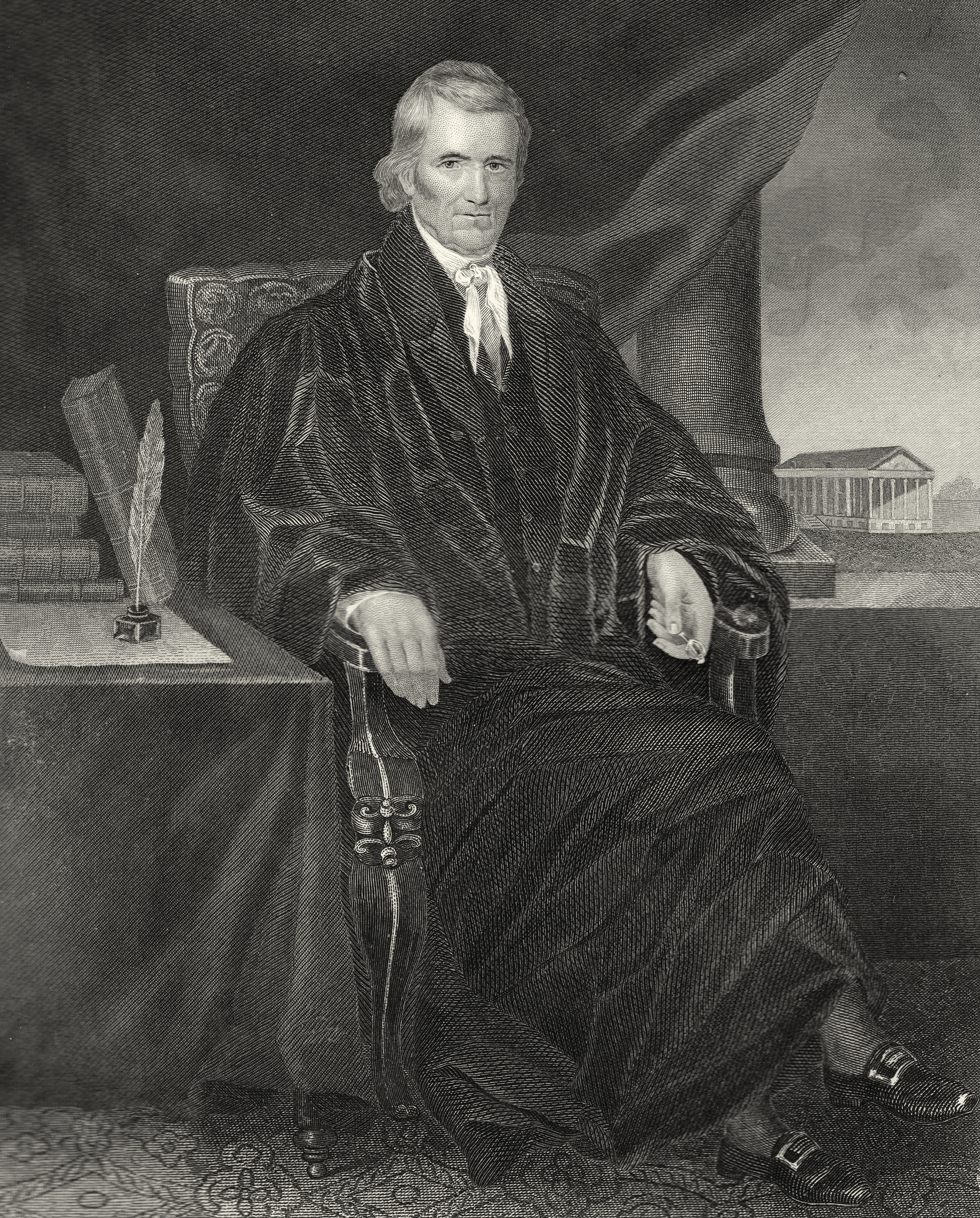

Late in 1800, the government had moved from Philadelphia to the new capital in Washington, D.C. Adams made appointments to government offices until his last day in office. One of his most important appointments was that of John Marshall as chief justice of the United States (see Marshall, John ).

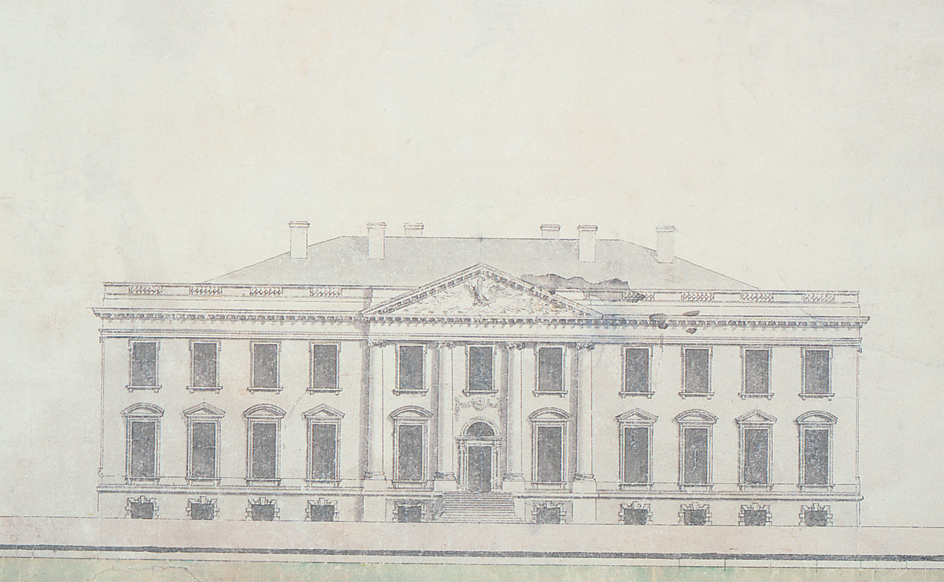

Life in the White House.

President Adams moved into the White House just a few months before the end of his administration. In one of his first letters from the White House, John wrote to Abigail, “I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof.”

The unfinished Executive Mansion stood in isolated splendor amid a dismal, swampy landscape. Abigail Adams wrote to her sister: “As I expected to find it a new country, with houses scattered over a space of 10 miles, and trees and stumps in plenty with a castle of a house—so I found it.” Only half a dozen rooms of the White House were finished. Mrs. Adams had to dry the laundry in the East Room, because no drying yard had been provided.

The unfinished condition of the White House made it hard to carry on official social functions. But John Adams and his wife worked to overcome their difficulties. As the first residents of the White House, they felt they should set a social tone appropriate to the home of the president. Mrs. Adams admired the courtly entertainments of Martha Washington and tried to follow her example.

Later years

John Adams was nearly 66 years old when he left the White House. His defeat, and the death of his son Charles, grieved him so much that he refused to stay in Washington for Jefferson’s inauguration. He hurried off for his home in Quincy on the morning of March 4, 1801. Adams devoted himself to farming, and to studying history, philosophy, and religion.

After Jefferson left office, he and Adams renewed their friendship. These two great Americans from North and South had met in Congress in 1775. Their friendship cooled steadily after about 1790, because they differed on the meaning of the French Revolution. But they forgot their political quarrels after retiring from public life.

By a remarkable coincidence, both men died on July 4, 1826. Adams died less than four months before his 91st birthday. His last words were: “Thomas Jefferson still survives.” Adams was buried in Quincy, Massachusetts.