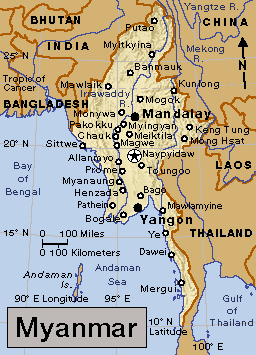

Myanmar << myahn MAHR >>, also called Burma, is a country in Southeast Asia. It is bordered by Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, Thailand, and the Bay of Bengal. Mountains in the west, north, and east of Myanmar enclose the Irrawaddy River Valley. The Irrawaddy River empties into the Bay of Bengal through many mouths, forming a delta. Yangon (also spelled Rangoon), Myanmar’s largest city, lies on the delta. Naypyidaw, in central Myanmar, is the capital.

The people of Myanmar are called the Burmese. The great majority of them are Buddhists and live in villages on the delta and in the Irrawaddy Valley. They make a bare living farming the land.

People have lived in what is now Myanmar since prehistoric times. Several kingdoms arose and fell in the region from the A.D. 1000’s to the 1800’s, when the United Kingdom conquered the country. The nation won its independence with the name Burma in 1948. In 1989, the military government announced that it had changed the official name of the country from the Union of Burma to the Union of Myanmar. In 2010, the name changed again, to the Republic of the Union of Myanmar. The United States and the United Kingdom opposed the military regime and still refer to the country as Burma.

Government

National government.

For many years, the military controlled Myanmar’s government. A council of generals came to power through a coup (military takeover) in 1988. A military group that comes to power in this way is called a junta. In the first decade of the 2000’s, the junta gradually relaxed its control over the country. An elected civilian government took power in 2011. In February 2021, however, the military staged another coup and again took control. To govern the nation, it installed a State Administrative Council headed by the commander in chief, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The council later named Min Aung Hlaing as prime minister.

Myanmar’s Constitution, which was adopted in 2008, guarantees the military a leading role in the government. The Constitution provides for a two-house legislature called the Union Assembly. The two houses are the People’s Assembly and the National Assembly. Members of both houses serve five-year terms. About one-fourth of the seats in both houses are reserved for military officers. Voters elect the remaining members of both houses. The legislature selects the country’s president.

In 2016, human rights activist Aung San Suu Kyi became the unofficial head of the Burmese government. The Constitution bars anyone whose children are citizens of another country from serving as Myanmar’s president, and her children are British citizens. Her National League for Democracy (NLD) won a controlling majority in legislative elections held in 2015. In 2016, the new government appointed Aung San Suu Kyi to serve as state counselor, a role above that of the president created specifically for her. On Feb. 1, 2021, the military seized control of the government and arrested many of the nation’s government officials, including the president and Aung San Suu Kyi.

Local government.

Myanmar is divided into 15 administrative units. They consist of 7 regions, 7 states, and the capital city of Naypyidaw. The regions are inhabited chiefly by Myanmar’s largest ethnic group, the Burmans. Other ethnic groups live mainly in the states. The regions and states are divided into many smaller units.

Armed forces.

Myanmar has an army, navy, and air force. Most members of the military serve in the army. Myanmar also has a large national police force that is a branch of the armed forces.

People

Ancestry.

Most Burmese are descendants of various peoples who moved into the region from central Asia. The Burmans, Myanmar’s largest ethnic group, make up about two-thirds of the population. Other ethnic groups include the Karen, Shan, Rakhine (also called Arakanese), Chin, Kachin, Mon, Naga, and Wa. Most members of these groups live in the hills and mountains bordering Myanmar. Each of these hill peoples seeks to preserve its own culture. Since 1948, several groups have fought against the government to obtain more rights. Some Chinese and Indian people live in Myanmar’s cities and towns.

Languages.

Burmese is the official language of Myanmar. It is related to Tibetan. Nearly all the people speak Burmese, and many of them also speak English. In addition, many hill peoples have languages of their own.

Religion.

About 90 percent of Myanmar’s people belong to the Theravada school of Buddhism. Buddhism, which teaches that people can find happiness only by freeing themselves of worldly desires, strongly influences family and community life. Other religious groups in Myanmar include Christians, Hindus, and Muslims.

Way of life.

The majority of Myanmar’s people live in farm villages. Most villages consist of about 50 to 100 bamboo houses with thatch roofs. The houses are built on poles above the ground for protection against floods and wild animals. Most villages have a Buddhist monastery, which is the center of much social as well as religious activity. Boys spend from a few days to several months in the monastery after an adulthood ceremony called shin-pyu. In the ceremony, the boys’ heads are shaved to symbolize their temporary rejection of the world. Girls mark their entry into adulthood with an earlobe-piercing ceremony called nahtwin, after which they receive their first pair of earrings.

In towns and cities, many people live in small brick or concrete buildings and work for the government or in trade or industry. City life has more leisure and cultural activities than rural life and moves at a faster pace. But most city people keep close ties with their family and ethnic group, and religion remains important to them.

In both rural and urban areas, men and women usually wear a longyi, a long, tightly wrapped skirt made from a cylinder of cotton cloth. Women’s longyis have bright colors and patterns and are bound at the side. Men’s longyis often have a checked pattern and are bound in front. With the longyi, women wear a blouse, and men wear a shirt. On special occasions, men may wear a silk jacket and a gaungbaung, a small headdress made of cloth wrapped around a wicker frame.

Burmese women have more rights than do women in some other Asian countries. In Myanmar, a woman keeps her name after marriage and owns property equally with her husband. In most Burmese families, the mother manages finances and runs the household. Many of the women work outside the home, and some of them own or manage a business.

Food.

The people of Myanmar eat rice with almost every meal. The rice is often flavored with chili peppers. Fish or vegetables may also be added. The Burmese like fish, shrimp, and chicken but rarely eat beef or other red meats. Seafood and meat seasonings include onions, garlic, ginger, and ngapi, a sharp paste made from preserved fish or shrimp. The Burmese also like bananas, citrus fruits, and Southeast Asian fruits called durians.

Recreation.

Popular spectator sports include soccer and a form of boxing that allows hitting with any part of the body. The favorite participant sport is chinlon, in which a ball of woven cane is passed from player to player by hitting it with the feet, knees, or head.

The Burmese people enjoy many festivals. The most popular one is held for three days before the Buddhist New Year begins, usually in April during the hot, dry season. People dump water on one another in a rowdy celebration that leaves everyone soaked. The New Year festival and many others include a pwe, an all-night performance by actors, dancers, singers, and clowns. Loading the player...

Burmese traditional drama music

Education.

Most of Myanmar’s people aged 15 or older can read and write. Myanmar law requires children from 5 through 10 years old to attend school. The government claims to offer free education from kindergarten through the university level, but education beyond elementary school is available only in the larger towns and cities. Major universities are in Yangon and Mandalay. Myanmar also has numerous colleges and technical schools.

The arts.

The best-known Burmese works of art are the thousands of pagodas (towerlike temples) found throughout the country. The most famous pagoda is the Shwe Dagon pagoda in Yangon. The golden-domed structure rises 326 feet (99 meters) above a marble platform on a hilltop. The ancient city of Pagan (also spelled Bagan) has hundreds of pagodas. Burmese craftworkers are known for their woodcarving, lacquerware, and jewelry.

The land and climate

Land regions.

Myanmar has three main land regions. They are (1) the Eastern Mountain System, (2) the Western Mountain Belt, and (3) the Central Belt.

The Eastern Mountain System

separates Myanmar from Thailand, Laos, and China. The region includes the long, narrow Tenasserim Coast bordering the Andaman Sea and the hilly Shan Plateau to the north. Some of the world’s finest jade and rubies come from the region. The area also has deposits of silver, lead, and zinc.

The Western Mountain Belt

is a region of thick forests along the border between Myanmar and India. A group of low mountains called the Arakan Yoma forms the southern part of the region and extends to the Bay of Bengal. A narrow plain of rich farmland borders the bay.

The Central Belt

lies between the eastern and western mountain regions. It includes Myanmar’s highest mountains in the far north. Hkakabo Razi, the tallest peak, rises 19,296 feet (5,881 meters) above sea level. The Central Belt consists chiefly of the Irrawaddy and Sittang river valleys. The Irrawaddy River flows about 1,250 miles (2,010 kilometers) down the middle of the country to the Bay of Bengal. It is Myanmar’s major transportation route. The 350-mile (563-kilometer) Sittang River lies east of the Irrawaddy. Farmers use water from the rivers to irrigate their rice fields.

Climate.

Most of Myanmar has a tropical climate. Temperatures in Mandalay, in central Myanmar, average 68 °F (20 °C) in January and 85 °F (29 °C) in July. Temperatures in Yangon, on the delta, average 77 °F (25 °C) in January and 80 °F (27 °C) in July. Myanmar has three seasons: (1) rainy, (2) cool, and (3) hot.

The rainy season,

during which Myanmar receives nearly all its rain, lasts from late May to October. Rainfall varies greatly in each region. For example, the Mandalay area receives only about 30 inches (76 centimeters) of rain a year. The Tenasserim Coast, however, is drenched with over 200 inches (510 centimeters). The heavy rainfall is brought by seasonal winds called monsoons, which sweep northeastward from the Indian Ocean.

The cool season

lasts from late October to mid-February. Temperatures are lowest at this time, though the climate remains tropical throughout most of Myanmar.

The hot season

lasts from late February to about mid-May. During this season, temperatures often top 100 °F (38 °C) in many parts of Myanmar.

Economy

Myanmar’s economy is based mainly on agriculture. For many years, a military government ruled Myanmar. This government owned all the land, and government factories produced most of the industrial output. In 2010, an elected civilian government took power and began relaxing economic constraints.

Agriculture, forestry, and fishing.

Rice is Myanmar’s chief crop, and rice fields cover about half the farmland. Much of the rice is exported. Other crops include beans, corn, cotton, fruits, peanuts, rubber, sesame seeds, sugar cane, and vegetables. Most crops are raised on small family farms. Farmers also raise beef and dairy cattle, chickens, and hogs.

Forests cover about half of Myanmar. Much of the world’s teakwood grows there. Fish and shellfish are caught in Myanmar’s rivers and coastal waters. Many people also raise fish in village ponds.

Manufacturing.

Manufacturing plays a growing role in Myanmar’s economy. Manufactured products include cement, clothing, fertilizer, pharmaceuticals (medicinal drugs), processed foods, and wood products. Yangon is the chief industrial center.

Mining.

Myanmar has a wealth of mined products, including copper, lead, natural gas, tin, tungsten, and zinc. It is also rich in jade and such precious stones as rubies and sapphires. But much of Myanmar’s mineral wealth is undeveloped.

Service industries.

Many service industries workers are government administrators. Others work for schools, hospitals, and other institutions that provide community services. Hotels, restaurants, and shops benefit from the hundreds of thousands of tourists who visit Myanmar each year. These tourists travel from China, France, Japan, Thailand, and other countries.

Trade.

Clothing, food products, and natural gas account for much of Myanmar’s export income. In addition, there are extensive illegal exports of gems and opium. The nation’s leading imports include many kinds of consumer goods as well as machinery, petroleum products, and transportation equipment. Myanmar’s leading trade partners include China, Japan, Singapore, and Thailand.

Transportation.

Freight travels by riverboats on Myanmar’s inland waterways, and by railroads and trucks. Most roads are unpaved. Few people own an automobile. Many travel between cities on boats. Oxcarts are common in rural areas. Myanmar’s chief seaports include Moulmein, Sittwe, and Yangon. Mandalay is a major inland port and transportation center. Mandalay, Naypyidaw, and Yangon have international airports.

Communication.

The government of Myanmar controls much of the mass communication. It publishes daily newspapers in Burmese and English. In 2013, the government allowed privately owned newspapers to be published. Government radio and television programs are broadcast in Burmese, English, and local languages.

History

Early days.

The first known people to live in what is now Myanmar were the Mon. They shared a culture with the Khmer, a people who lived in what is now Cambodia. The Mon moved into the Myanmar region as early as 3000 B.C. and settled near the mouths of the Salween and Sittang rivers. The peoples who came later migrated from an area in central Asia that is now southwestern China. The Pyu arrived in the A.D. 600’s. The Burmans, Chin, Kachin, Karen, and Shan came during the 800’s. Most of these peoples lived apart from one another and kept their own cultures.

In 1044, a Burman ruler named Anawrahta united the region and founded a kingdom that lasted nearly 250 years. The kingdom’s capital, Pagan, lay on the Irrawaddy River in the central part of the country. The Burmans adopted features of the Mon and Pyu cultures, including Theravada Buddhism. Mongol invaders led by Kublai Khan captured Pagan in 1287, shattering the kingdom. A new Burman kingdom arose at Toungoo during the 1500’s. It was brought down by a Mon rebellion in 1752.

British conquest and rule.

The last Burman kingdom was founded by Alaungpaya after the Mon rebellion. Three wars with the British—triggered by Burmese resistance to the United Kingdom’s commercial and territorial ambitions—led to the kingdom’s collapse. The first war was fought from 1824 to 1826, the second in 1852, and the third in 1885. In these wars, the British gradually conquered all of what was then called Burma.

After the third war with the United Kingdom, Burma became a province of India, which the British ruled. Under British control, Burma’s population and economy grew rapidly. But educated Burmese called for Burma’s separation from India and eventual independence. The Burmese protests led the United Kingdom to set up a legislature in the 1920’s that gave the people a small role in the government.

Protests against British rule continued, however. During the early 1930’s, a former Buddhist monk named Saya San led thousands of peasants in an unsuccessful rebellion. At the same time, university students founded the All-Burma Students’ Union to work for independence. The students called one another Thakin (Master), a title of respect that had been used before only in addressing the British. Leaders of the movement included Thakin Nu and Thakin Aung San. They organized a student strike in 1936. The United Kingdom separated Burma from India in 1937 and gave the Burmese partial self-government. But the struggle for full independence continued.

World War II (1939-1945).

In 1942, Japan conquered Burma. The Thakins had formed the Burma Independence Army, which helped the Japanese drive the British out of Burma. The Japanese declared Burma independent in 1943, but they actually controlled the government. The Burmese disliked Japanese rule even more than British rule. To fight the Japanese, the Thakins formed the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL), led by General Aung San. The AFPFL helped the United Kingdom and other Allied powers regain Burma in 1945.

Independence.

Following Japan’s defeat, the British returned to power in Burma. The AFPFL had become a strong political party, however, and it challenged British control. The British could not govern the country without AFPFL support. They decided in 1947 to name AFPFL President Aung San prime minister of Burma, but he was assassinated before independence came. U Nu , who had been vice president of the AFPFL, became the party’s president, and the British appointed him prime minister. Burma won full independence on Jan. 4, 1948.

The new Burmese government faced many problems. Some Communists rebelled against the government in 1948. Various ethnic groups also fought the new government. U Nu’s leadership won the support of most Burmese, however. The AFPFL overwhelmingly won elections in 1951 and 1956, though Communist and rebel ethnic groups continued to fight the government.

In 1958, a split developed between U Nu’s followers and another AFPFL group. The split threatened to plunge Burma into a deeper civil war. U Nu asked General Ne Win to set up a military government temporarily. Ne Win restored order. He ruled until elections were held in 1960. U Nu’s faction won a landslide victory, and he again became prime minister. But he could not control the political and ethnic disputes.

To hold Burma together, Ne Win seized the government in a bloodless take-over in March 1962. He suspended the Constitution and set up a Revolutionary Council of military leaders to rule Burma.

Socialist republic.

Ne Win and his Revolutionary Council wanted to make Burma a socialist nation. They explained their ideas in The Burmese Way to Socialism, a document that guided many of the government’s plans. In July 1962, Ne Win and the council founded the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP). Until 1988, the BSPP was the only political party allowed in Burma. The government began to take strict control of the economy. For several years thereafter, farm production fell, and consumer goods disappeared into the black market. The government rejected most foreign aid and restricted visits by foreign reporters and tourists. It also closed or took over all privately owned newspapers and schools. Student strikes were ended by army gunfire.

On March 2, 1974, the country adopted a new Constitution that officially created the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma, with Ne Win as president. The Constitution reestablished elections, but the BSPP still held all power. The government removed some restrictions on agriculture and began to accept more foreign aid. Ne Win resigned as president in 1981 but remained head of the BSPP and Burma’s most powerful leader.

Military rule.

In 1988, many Burmese demonstrated against one-party rule. Ne Win resigned as head of the BSPP in July. He suggested that economic reforms and multiparty elections might solve the nation’s problems. But protests continued into September. The army then overthrew the government, replacing it with the newly established State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). Before and after the coup, troops killed thousands of protesters.

In 1989, the SLORC changed the country’s name to the Union of Myanmar. It also arrested the leader of the National League for Democracy (NLD), Aung San Suu Kyi, the daughter of independence leader Aung San. She was placed under house arrest (confined to her home).

The SLORC allowed multiparty elections in 1990. The NLD won 60 percent of the vote and 80 percent of the seats in the legislature. But many of the elected representatives were imprisoned. The SLORC said it would not allow a transfer of power until a new constitution was written and approved, with a leading role for the military.

Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for her nonviolent struggle for democracy and human rights. The SLORC freed her from house arrest in 1995 but still restricted her travel.

The SLORC changed its name to the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) in 1997. Economic reforms opened the country to foreign and private businesses, but the economy still suffered from inflation and slow growth. Major nations withheld economic aid because of the SPDC’s human rights violations and its failure to open talks with the NLD. The United Nations and its Commission on Human Rights repeatedly criticized Myanmar on these issues.

During much of the late 1900’s, rebel groups fought the government and each other. Myanmar’s military rulers reached cease-fire agreements with most rebels in the 1990’s, but fighting continued with several of the largest groups.

The SPDC confined Aung San Suu Kyi to her home again from September 2000 to May 2002. In May 2003, after a violent clash between her supporters and pro-government militants, the SPDC took her into custody. She was allowed to return home in September but was kept under house arrest until 2010.

In November 2005, the Myanmar government began moving government offices to a new capital in the center of the country. By March 2006, most major government offices had moved there, though the city was still under construction. The government named the new capital Naypyidaw.

Beginning in August 2007, Buddhist monks led tens of thousands of people in mass protests against the government. The pro-democracy protests began after the government raised fuel prices. In September, the government banned gatherings and imposed a curfew in Yangon and Mandalay. In October, the government lifted the curfews.

In May 2008, Cyclone Nargis hit the coast of Myanmar near Yangon, causing massive amounts of damage. The cyclone killed about 140,000 people. The international community severely criticized Myanmar’s government for its slow response to the disaster and its unwillingness to accept foreign aid.

Recent developments.

In 2010, the government announced new election laws banning anyone with a criminal conviction from belonging to a political party. The government also required all active political parties to re-register. The NLD refused to obey, claiming the government’s new laws were undemocratic. The party was forced to disband. Myanmar held parliamentary elections in November 2010 under a new constitution. The elections were intended to serve as a transition to more democratic rule. The Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), a new party backed by the junta and including many former junta members, won the most seats. The new parliament elected former Prime Minister Thein Sein as president.

Following the election, the government released Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest. In 2011, the new government was sworn in, and the State Peace and Development Council was dissolved. That year, the NLD also was allowed to re-register as an official political party. Aung San Suu Kyi was elected to Myanmar’s parliament in a 2012 by-election (special election to fill a vacant seat).

The new government relaxed many of the country’s political and economic restrictions. As a result, many countries and international aid organizations eased sanctions against Myanmar. However, many human rights advocates remained critical of the country’s record, especially for its treatment of the country’s Rohingya Muslim minority. Many Rohingya families had lived in Myanmar for decades, but the government considered them illegal immigrants and limited their rights. In 2012, violent clashes erupted between Buddhists and Rohingya. In the following years, Myanmar’s government further restricted the rights of the Rohingya, leading an increasing number to attempt to flee the country.

Under the leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, the NLD won a controlling majority in parliamentary elections held in 2015. However, because of constitutional changes made by the USDP government, she was not eligible to serve as Myanmar’s president. The new parliament elected Htin Kyaw, one of her closest allies, as president. It created the position of state counselor, a role above that of the president, and appointed Aung San Suu Kyi to the role in 2016. In 2018, Htin Kyaw resigned. The parliament elected Win Myint, former speaker of the lower house of parliament and another close ally of Aung San Suu Kyi, as president.

In 2017, violence between Rohingya militants and government forces, including military attacks on Rohingya villages, caused hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. In 2019, the International Court of Justice, the highest court of the United Nations, began a hearing into accusations that Myanmar’s military had committed genocide in its campaign against the Rohingya. Aung San Suu Kyi was widely criticized by the international community for defending Myanmar’s actions before the court. In 2020, the court called on Myanmar to protect the Rohingya during the proceedings.

The NLD won a large majority of the seats in the 2020 parliamentary elections. However, the USDP and the military objected to the election results. On Feb. 1, 2021, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, the nation’s commander in chief, led a military coup that seized control of the government. The military arrested Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, and a number of other government officials. Vice President Myint Swe, a former general, was appointed acting president. He declared a one-year state of emergency and turned over control of all branches of the government to the commander in chief. The next day, a State Administrative Council was formed to run the government, with Min Aung Hlaing as its chairman.

In the following weeks, hundreds of thousands of Myanmar’s citizens participated in protests against the military takeover. The military’s security forces began to use violence against peaceful protesters. They also arrested thousands of people suspected of opposing the government. In June, the United Nations General Assembly called for an end to the military takeover and for the release of the imprisoned civilian leaders. It also called for an international embargo (restriction) on the sale of weapons to Myanmar.

In late July 2021, Myanmar’s State Administrative Council officially canceled the results of the 2020 election. The next month, it extended the state of emergency for another two years and announced the formation of a caretaker government with Min Aung Hlaing as prime minister.

Meanwhile, the violence spread into the countryside as armed groups began to form to oppose the military takeover of the government. In April 2023, an air strike by Myanmar’s air force killed over 150 people—including women and children—in the village of Pazigyi, in rebel-held territory. In October 2023, militant organizations from three ethnic minority groups—the Rakhine, the Kokang, and the Ta’ang—launched a major military offensive against Myanmar’s government. The rebel forces, known as the Brotherhood Alliance, seized several towns and military posts.