Mythology is a body of stories told to explain the world and its mysteries. Such stories are known as myths. People have always tried to understand why certain things happen. For example, they have wanted to know why the sun rises and sets and what causes lightning. They have also wondered how Earth was created and how and where humanity first appeared. Today, people have scientific answers and theories for many such questions. But in earlier times—and in some parts of the world today—people lacked the knowledge to provide scientific answers. They therefore explained natural events using stories about gods, goddesses, and heroes. For example, the Greeks had a story to explain the existence of evil and trouble. They believed that at one time the world’s evils and troubles were kept in a box. They escaped when the container was opened by Pandora, the first woman.

In early times, every society developed its own myths, which played an important part in the society’s religious life. This religious significance has always separated myths from similar stories, such as folk tales and legends. The people of a society may tell folk tales and legends for amusement, without believing them. But they usually consider their myths sacred and completely true.

Most myths concern divinities (divine beings). These divinities have supernatural powers—powers far greater than any human being has. But in spite of their supernatural powers, many gods, goddesses, and heroes of mythology have human characteristics. They are guided by such emotions as love and jealousy, and they experience birth and death. A number of mythological figures even look like human beings. In many cases, the human qualities of the divinities reflect a society’s ideals. Good gods and goddesses have the qualities a society admires, and evil ones have the qualities it dislikes.

By studying myths, we can learn how different societies have answered basic questions about the world and the individual’s place in it. We study myths to learn how a people developed a particular social system with its many customs and ways of life. By examining myths, we can better understand the feelings and values that bind members of society into one group. We can compare the myths of various cultures to discover how these cultures differ and how they resemble one another. We can also study myths to try to understand why people behave as they do.

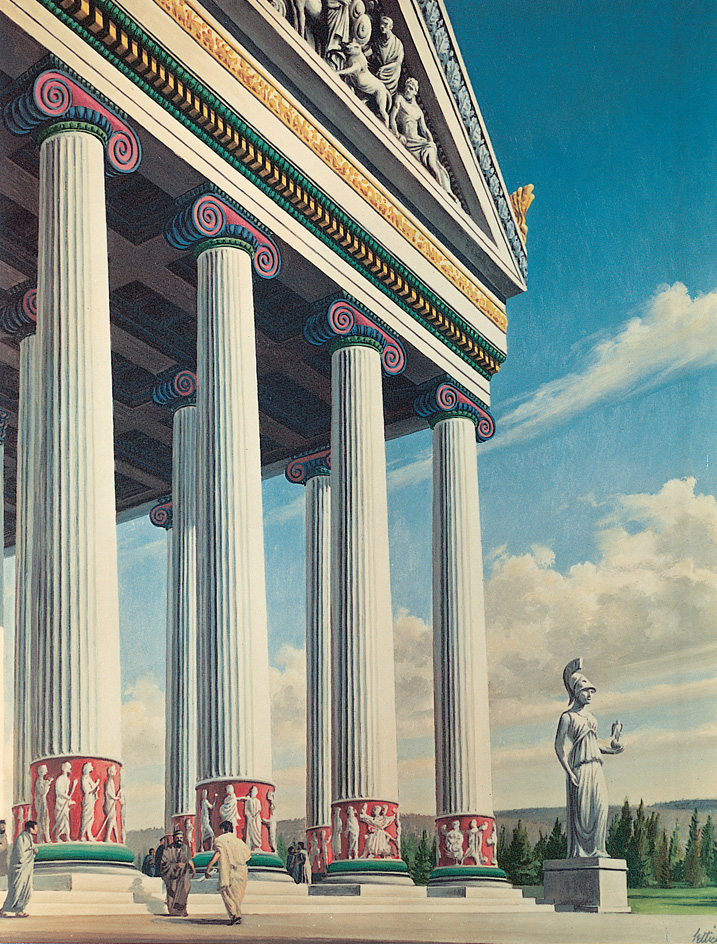

For thousands of years, mythology has provided inspiration for much of the world’s great art. Myths and mythological characters have inspired masterpieces of architecture, literature, music, painting, and sculpture.

Types of myths

Most myths can be divided into two groups—creation myths and explanatory myths. Creation myths try to explain the origin of the world, the creation of human beings, and the birth of gods and goddesses. All early societies developed creation myths.

Explanatory myths try to explain natural processes or events. The Norse, who lived in medieval Scandinavia, believed that the god Thor made thunder and lightning by throwing a hammer at his enemies. The ancient Greeks believed that the lightning bolt was a weapon used by the god Zeus. Many societies developed myths to explain the formation and characteristics of geographic features, such as rivers, lakes, and oceans.

Some explanatory myths deal with illness and death. Many ancient societies—and some present-day societies—believed that a person dies because of some act by a mythical being. The people of the Trobriand Islands in the Pacific Ocean believed that men and women were immortal when the world was new. When people began to age, they swam in a certain lagoon and shed their skin. They quickly grew new skin, renewing their youth. One day, a mother returned from the lagoon with her new skin. But her unexpected youthful appearance frightened her little daughter. To calm the child, the mother returned to the lagoon, found her old skin, and put it back on. From then on, according to this myth, people could not avoid death.

Some myths stress proper behavior through the actions of particular gods and heroes. The ancient Greeks strongly believed in moderation—that nothing be done in excess. They expressed this ideal in the behavior of Apollo, the god of purity, music, and poetry. Myths about national heroes also call attention to shared moral values. One example is the story about young George Washington’s confession that he had cut down his father’s cherry tree. The story has no basis in fact. Yet many people like the story because it emphasizes the quality of honesty.

Elements of myths

Myths tend to share several common elements. These include mythical beings, places, and symbols.

Mythical beings

fall into several groups. Many gods and goddesses resemble human beings, even though they have supernatural powers. These gods and goddesses are born, fall in love, fight with one another, and generally behave like the people who believe in them. Such divinities are called anthropomorphic, from Greek words meaning in the shape of man. Greek mythology has many anthropomorphic divinities, including Zeus, the most important Greek god.

Another group of mythical beings resemble animals. These characters are called theriomorphic, from Greek words meaning in the shape of an animal. Many theriomorphic beings appear in Egyptian mythology. For example, the Egyptians sometimes represented their god Anubis as a jackal or a dog.

A third group of mythical beings are neither fully human nor fully animal. An example is the famous sphinx of Egypt, which has a human head and a lion’s body.

Human beings play an important part in mythology. Many myths deal with the relationships between mortals and divine beings. Some mythical mortals have a divine father and a mortal mother. These human characters are called heroes, though they do not always act heroically in the modern sense. Most stories about heroes are called epics rather than myths, but the difference between the two is not always clear.

Mythical places.

Many myths describe places where demons, gods and goddesses, or the souls of the dead live. Often, the gods and goddesses live in the sky or on top of a high mountain. Their lofty dwelling place enables the divinities to see everything and puts them beyond the reach of mortals.

Mythical places exist in the mythologies of most peoples. Perhaps the most sacred place in Japanese mythology is Mount Fuji, the tallest mountain in Japan. During part of their history, the Greeks believed their divinities lived on a mythical Mount Olympus that was separate from the visible Mount Olympus in northern Greece.

The Greeks also believed in mythical places beneath the ground, such as Hades, where the souls of the dead lived. The Norse believed in Hel, an underground home for the souls of all dead people, except those killed in battle. The souls of slain warriors went to Valhalla, which was a great hall in the sky. The Inuit believe that their sea goddess, Sedna, lives in a world under the ocean.

Symbols

form an important part of mythology. The Greeks symbolized the sun as the flaming chariot of the god Helios. The Egyptians represented the sun as a boat.

In myths, animals, human beings, and plants have all stood for ideas and events. Some peoples adopted the serpent as a symbol of health because they believed that by shedding its skin, the serpent became young and well again. The Greeks portrayed Asclepius, the god of healing, holding a staff with a serpent coiled around it. The staff is often confused with the caduceus of the god Mercury, which has two snakes coiled around it. Today, both symbols are used as emblems of the medical profession. In Babylonian mythology, the hero Gilgamesh searched for a special herb that made anyone who ate it immortal. In the Bible, on the other hand, Adam and Eve lost their immortality by eating the forbidden fruit.

Comparing myths

Scholars often study the myths of various societies by comparing them with one another. Myths can be compared on the basis of generic relationships, genetic relationships, or historical relationships.

Generic relationships

result from similarities in the way people react to common features in their environment. For example, both the ancient Greeks and a Polynesian people of New Zealand called Māori had myths that described how the earth became separated from the sky.

Genetic relationships

occur in myths that descend from a common myth. For example, a large society may develop a particular myth. Then, for some reason, the society breaks up into several separate societies, each of which develops its own version of the myth. These myths have a genetic relationship.

Myths about the Greek god Zeus and the ancient Indian god Indra, for example, resemble each other in many ways. Each is a sky god, and each uses a lightning bolt as his chief weapon. These similarities can be explained by the fact that the ancient Greeks and the people of ancient India descended from a common culture, the Indo-European community. The Indo-Europeans lived several thousand years ago in the area north of the Black Sea, in southeastern Europe. This culture worshiped a warrior god who ruled the sky. One group of Indo-Europeans migrated westward to what is now Greece. There, they developed a sky god who became known as Zeus. Another group of Indo-Europeans, the Aryans, migrated southward into northern India. They developed the warlike sky god Indra. Myths about Zeus and Indra thus share a genetic relationship.

Historical relationships

occur when similar myths develop among cultures that share no common origin. For instance, many ancient Middle Eastern societies had a myth in which several generations of sons overthrew their fathers, who ruled as gods or kings. Variations of this myth appeared in Greece and Iran, among the Hittites in what is now Turkey, and among the Phoenicians, who lived mainly in what is now Lebanon. Many scholars believe all versions of the myth came from a Babylonian myth dating from about 2000 B.C. Historical relationships develop when common themes such as this one are spread among people of different cultures through trade and other cultural interaction.

Interweaving relationships

appear in many myths. Many examples can be seen in a long poem called the Theogony, written in the 700’s B.C. by the Greek poet Hesiod. The Theogony, one of the earliest sources of information about Greek religion, describes the origin of the world and the history of the Greek gods.

Scholars have observed that the myths in the Theogony share generic, genetic, and historical relationships with myths of other cultures, including all of the examples mentioned. The description of how the earth became separated from the sky in the Theogony is generically related to a similar Māori myth. Zeus, a major figure in the Theogony, genetically resembles the Indian god Indra. The Theogony also contains a description of how successive generations of Greek gods overthrew their fathers, which is historically related to similar myths in other cultures of the ancient Near and Middle East. The historical similarities in the myths suggest that the Greeks had cultural interactions with the peoples of the Middle East and borrowed and adapted themes from them in their own myths.

Middle Eastern mythology

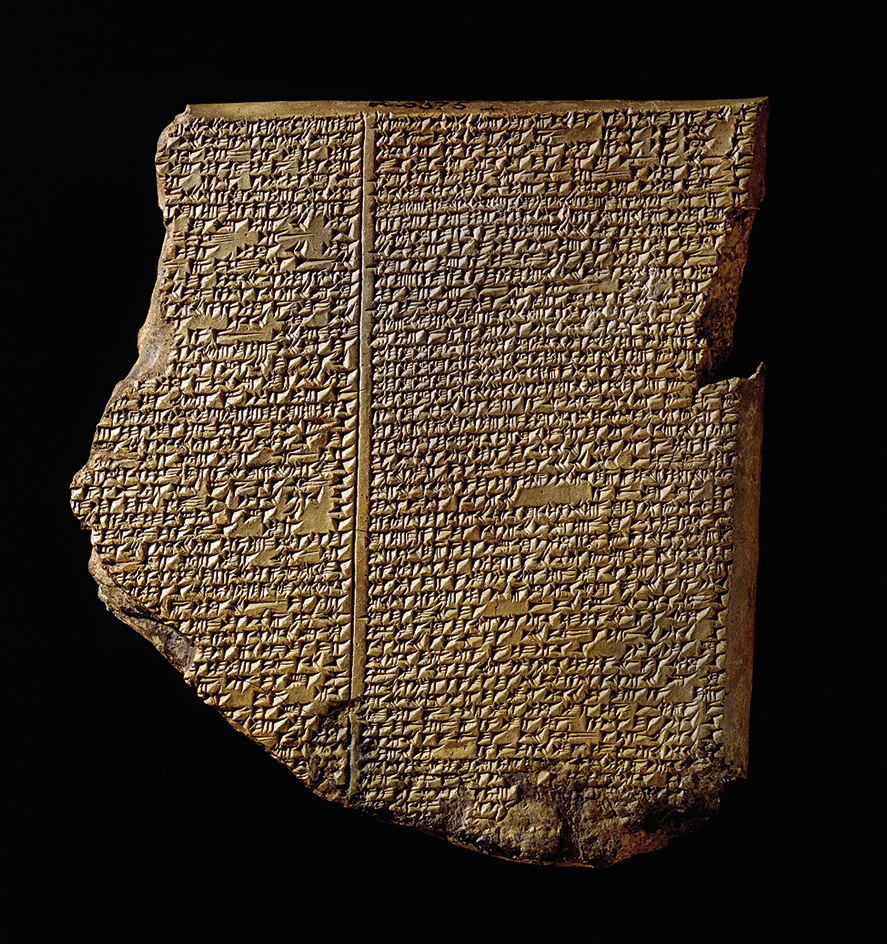

Some of the oldest surviving myths come from Mesopotamia, a region around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in what is now Iraq, eastern Syria, and southeastern Turkey. About 3500 B.C., people living in southern Mesopotamia built the world’s first cities. They invented the first system of writing about 3300 B.C. The term Sumerian came to refer to these people, and the region they inhabited was later called Sumer. Sumer was later conquered by nearby peoples, the Akkadians, the Assyrians, and finally the Babylonians. However, the conquerors adopted and spread the myths of the Sumerians.

Sumerian mythology.

The Sumerian creation myths are described in an epic poem known as the Enuma Elish. This poem was first written down around 1100 B.C., but it had existed for hundreds of years before as an oral tradition. The Sumerians believed that the universe emerged from a dark ocean, embodied in the goddess Nammu. She gave birth to the sky-father An and the earth-mother Ki << kee >>. Nammu also gave birth to Enki << ehn KEE >>, the god of wisdom. An and Ki, in turn, gave birth to Enlil << ehn LIHL >>, the god of air. Later, with the help of Enki, An and Ki created all of Earth’s plants and animals.

In addition to these four primary gods, Sumerian myths described many lesser gods. Some of them were responsible for elements of the natural world. These divinities included Ashan, the goddess of grain; Lahar, the goddess of cattle; and Ishkur, god of the winds. Other gods presided over the products of human technology. They included Enkimdu, god of canals and ditches, and Mushdamma, god of houses. Three other deities served as advisers to the four major deities. They were Nanna, god of the moon; Utu, god of the sun and justice; and Inanna (also called Ishtar), goddess of fertility, war, and civilization.

An and Enlil assigned the gods, goddesses, and kings their powers and regions of influence. Enki and Ki created seven human beings out of clay to serve the gods, but each was flawed in some way. Enlil assembled a series of divine laws called the me << may >> and gave them to Enki. Enki gave the me to humankind, and thus organized human civilization.

The influence of Sumerian mythology.

Elements of Sumerian myths persisted for hundreds of years in the Middle East. Many scholars see its influence in the Judaic, Islamic, and Christian traditions. For example, each of these traditions depicts the world emerging from a deep, empty space after divine action separates the heavens from the earth. All four traditions also have stories about a garden paradise. In the Sumerian tradition, this garden, called Dilmun, is described as pure, bright, and flowing with sweet water. In Dilmun, the god of wisdom Enki has sexual relations with an earth goddess called Ninhursag << NEEN hur sahg >>, which means Lady of the Mountain. In some versions of the story, Ninhursag is identified with the earth-mother Ki. Ninhursag buries Enki’s semen (fertilizing fluid) in the ground, where it sprouts into eight new plants. Enki eats the plants and is cursed for doing so. He is cured only after Ninhursag creates eight healing properties, one for each plant. Scholars have noted many parallels between the Sumerian myth and the story of Adam and Eve in the Bible, in which eating forbidden fruit brings with it a curse.

Another parallel with Christianity, Islam, and Judaism is found in the story of Ziusudra << zee oo SOO druh >>, a Sumerian king. In this story, the gods decide to destroy humanity with a great flood. Enki warns Ziusudra of the disaster. Ziusudra builds a boat and survives the deluge. After seven days, Utu, the sun-god, disperses the waters and Ziusudra and his wife step out onto dry land. Ziusudra and his wife make a sacrifice to the gods and are rewarded with eternal life. Ziusudra is sometimes called the “Sumerian Noah” because his story resembles the story of Noah in the Bible.

Babylonian mythology.

Babylon, a great city on the banks of the Euphrates River, served as the capital of the ancient region of Babylonia and as a major religious center of the ancient world from about 1894 B.C. until 539 B.C. The Babylonians combined old stories about Sumerian gods with newer stories.

One of the most famous of these Babylonian stories of mixed origin is the Epic of Gilgamesh. It describes the adventures of the hero Gilgamesh, who struggles with the problem of being mortal. The earliest verses were composed in southern Mesopotamia before about 2000 B.C. Fragments of the story appear in writings found in Syria and Turkey, showing that the tale was popular throughout the ancient Middle East. The Epic of Gilgamesh also includes an account of a flood that resembles the story of Noah’s ark in the Bible. Many scholars believe the Mesopotamian myths and Biblical accounts are related. See Gilgamesh, Epic of.

Babylonian creation myths differ from Sumerian creation stories. The Babylonians believed the universe arose from the fierce female sea monster called Tiamat << TEE ah maht >> , rather than from the gentle ocean goddess Nammu of Sumerian mythology. Scholars believe Tiamat may be the basis for Leviathan, a giant sea serpent described in the Bible, and also the inspiration for Typhon, a monster from Greek mythology. According to the Babylonian myth, the god Ea kills Tiamat’s mate, Apsu, leading Tiamat to wage war against all the gods. Marduk later defeats Tiamat and uses parts of her shattered body to create Earth.

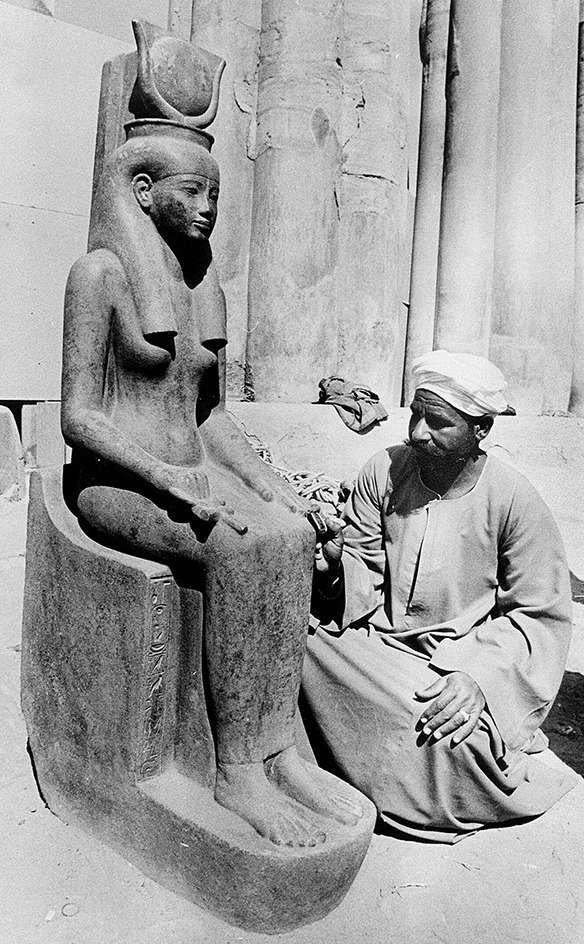

Egyptian mythology

The Nile River plays an important part in Egyptian mythology. As the Nile flows northward through Egypt, it creates a narrow ribbon of fertile land in the midst of a great desert. The sharp contrast between the fertility along the Nile and the wasteland of the desert became a basic theme of Egyptian mythology. The creatures that live in the Nile or along its banks became linked with many gods and goddesses.

The Great Ennead.

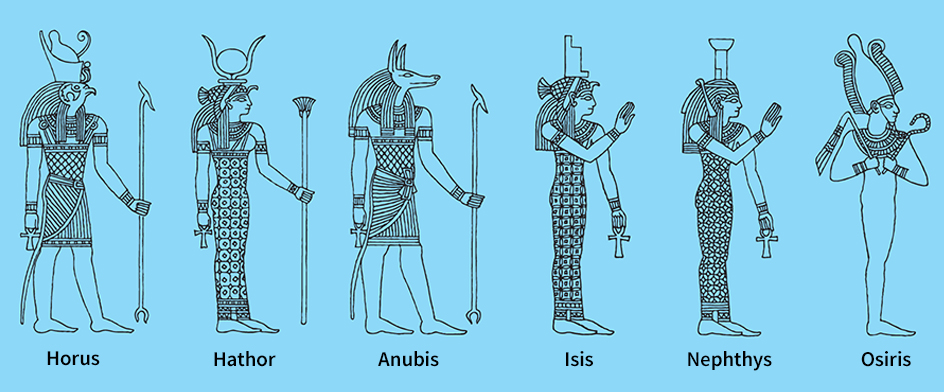

The earliest information scholars have about Egyptian mythology comes from hieroglyphics (picture writings) on the walls of tombs, such as the burial chambers in pyramids. These “pyramid texts” and other documents reveal that from about 3200 to 2250 B.C. the Egyptians believed in a family of nine gods. This family became known as the Great Ennead, from the Greek word ennea, meaning nine. The gods of the Great Ennead were Atum << AH tuhm >> , Shu << shoo >> , Tefnut << TEHF nuht >> , Geb << gehb >> , Nut << noot >> , Osiris << oh SY rihs >> , Isis << EYE sihs >> , Nephthys << NEHF thihs >>, and Horus << HOH ruhs >>.

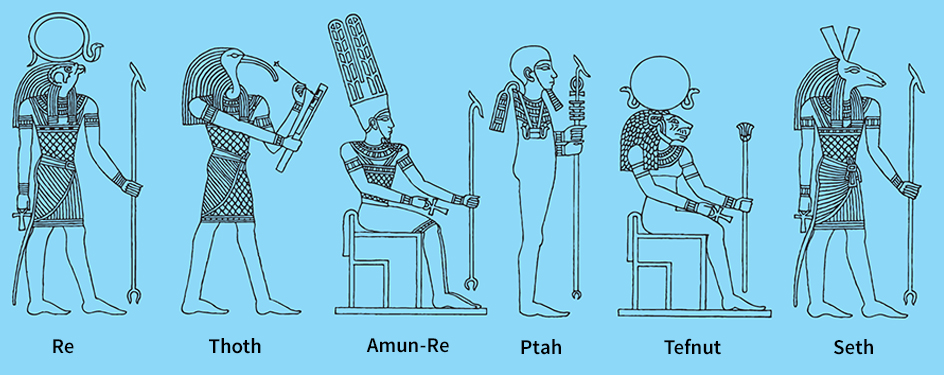

The term Ennead later came to include other deities as well. One of them was Nun << noon >> , who symbolized a great ocean that existed before the creation of the earth and the heavens. Another of these deities was the sun god, called Re or Ra. The Egyptians considered Re both the ruler of the world and the first divine pharaoh.

The first god of the Great Ennead was Atum. He was sometimes identified with the setting sun. Atum also represented the source of all gods and all living things. Re created a pair of twins, Shu and his sister, Tefnut. Shu was god of the air. Tefnut was goddess of the dew. Shu and Tefnut married and also produced twins, Geb and his sister, Nut. Geb was the earth god and the pharaoh of Egypt. Nut represented the heavens. Geb and Nut married, but the sun god Re opposed the match and ordered their father, Shu, to lift Nut away from Geb into the sky. Shu’s action separated the heavens from the earth. Nut had speckles on her body, and the speckles became the stars.

The Osiris myth.

In spite of their separation, Geb and Nut had several children. These included three of the most important divinities in Egyptian mythology—Osiris, Isis, and Seth.

Originally, Osiris may have been god of vegetation, especially of the plants that grew on the rich land along the Nile. The goddess Isis may have represented female fertility. Seth was god of the desert, where vegetation withers and dies from lack of water.

Seth had become pharaoh of Egypt after killing Osiris. But Horus, son of Osiris and Isis, then overthrew Seth and became pharaoh. Thus, the forces of vegetation and creation—symbolized by Osiris, Isis, and Horus—triumphed over the evil forces of the desert, symbolized by Seth. But more important, Osiris had cheated death. The Egyptians believed that if Osiris could triumph over death, so could human beings.

Other Egyptian divinities

included Hathor, Horus’s wife; Anubis << ah NOO bihs >> ; Ptah << puh TAH >> ; and Thoth. Hathor became the protector of everything feminine. Anubis escorted the dead to the entrance of the afterworld and helped restore Osiris to life. The Egyptians also believed that Anubis invented their elaborate funeral rituals and burial procedures. Ptah invented the arts. Thoth invented writing and magical rituals. He also helped bring Osiris back to life.

Many animals appear in Egyptian mythology. The falcon and the scarab, or dung beetle, were two animals that symbolized the sun god (see Scarab ). The Egyptians considered both the cat and the crocodile to be divine.

Between 1554 and 1070 B.C., various local divinities became well known throughout ancient Egypt. Some of them became as important as the gods and goddesses of the Ennead. The greatest of these gods was Amun. His cult (group of worshipers) originally centered in Thebes. In time, Amun became identified with Re and was frequently known as Amun-Re. Amun-Re became perhaps the most important Egyptian divinity.

The influence of Egyptian mythology.

The divinities of ancient Egypt and the myths about them had great influence on the mythologies of many later civilizations. Egyptian religious ideas may also have strongly affected the development of Judaism and Christianity.

During the 1300’s B.C., the pharaoh Amenhotep IV chose Aten as the only god of Egypt. Aten had been a little-known god worshiped in Thebes. Amenhotep was so devoted to the worship of Aten that he changed his own name to Akhenaten. The Egyptians stopped worshiping Aten after Akhenaten died. However, some scholars believe the worship of this one divinity lingered among the people of Israel, who had settled in Egypt. These scholars have suggested that the cult of Aten may have inspired the Jewish and Christian belief in one God. See Akhenaten.

Greek mythology

The earliest record of Greek mythology comes from clay tablets dating back to the Mycenaean civilization, which reached its peak between 1400 and 1200 B.C. This civilization consisted of several cities in Greece, including Mycenae. The clay tablets describe Poseidon as the chief Mycenaean god. Poseidon later reappeared as a major figure in Greek mythology. The god Zeus, who would become the chief god in Greek mythology, played a lesser part in Mycenaean myths.

About 1200 B.C., the Mycenaean civilization fell. In the 1100’s B.C., Dorians from northwestern Greece moved into lands that had been held by the Mycenaeans. In the next 400 years, the Dorian and Mycenaean mythologies combined, helping form classical Greek mythology. See Dorians.

The basic sources for classical Greek mythology are three works that date from about the 700’s B.C.: the Theogony by Hesiod and the Iliad and the Odyssey, attributed to Homer. Hesiod and Homer rank among the greatest poets of ancient Greece. The Theogony and the Iliad and Odyssey include most of the basic characters and themes of Greek mythology.

The Greek creation myth.

The Theogony includes the most important Greek myth—the myth that describes the origin and history of the gods. According to the Theogony, the universe began in a state of emptiness called Chaos. The divinity Gaea << JEE uh >> , or Earth, arose out of Chaos. She immediately gave birth to Uranus, who became king of the sky. Gaea mated with Uranus, producing children who were called the Titans.

Fearing his children, Uranus confined them within the huge body of Gaea. Gaea resented the imprisonment of her children. With Cronus, the youngest Titan, she plotted revenge. Using a sickle provided by Gaea, Cronus attacked Uranus and castrated him—that is, removed his sex organs. Cronus then freed the Titans from inside Gaea and became king of the gods. During his reign, the work of creating the world continued. Thousands of divinities were born, including the gods or goddesses of death, night, the rivers, and sleep.

Cronus married his sister Rhea, who bore him three daughters and three sons. But Cronus feared that he, like Uranus, would be deposed by his children. He therefore swallowed his first five children as soon as they were born. To save her sixth child, Zeus, Rhea tricked Cronus into swallowing a stone wrapped in baby clothes. Rhea then hid the infant on the island of Crete. After Zeus grew up, he returned to challenge his father. He tricked Cronus into drinking a substance that made him vomit his children. The children had grown into adults while inside their father. Zeus then led his brothers and sisters in a war against Cronus and the other Titans. This war, called the Titanomachy, lasted 10 years. Zeus and his followers finally won the war. They exiled the Titans in chains to Tartarus, a dark region deep within the earth.

The victorious gods and goddesses chose Zeus as their ruler and agreed to live with him on Mount Olympus. The divinities who lived on Olympus became known as Olympians. Gaea, upset that her grandchildren had imprisoned her children, sent an army of giants and monsters to battle the Olympians. In a fierce war called the Gigantomachy, Zeus defeated the giants with the help of his brothers, his sisters, and many of his children.

Greek divinities

Three important gods became associated with the 12 Olympians. They were Hades, ruler of the underworld and brother of Zeus; Dionysus, god of wine and wild behavior; and Pan, god of the forest and pastures.

There were several groups of minor divinities in Greek mythology. Beautiful lesser goddesses called nymphs guarded various parts of nature. Nymphs called Dryads lived in the forest, and nymphs called Nereids lived in the sea. Three goddesses called Fates controlled the destiny of everyone. The Muses were nine goddesses of various arts and sciences. All these divinities became the subjects of specific myths and folk tales.

Greek mythology also has a number of partly mortal, partly divine beings called demigods. Heracles (called Hercules by the Romans) probably ranked as the most important demigod. Heracles symbolized strength and physical endurance. Another demigod, Orpheus, became known for his beautiful singing.

Nearly all the Greek gods, goddesses, demigods, and other divinities became the subjects of cults. Many cults became associated with cities. People of Delphi especially worshiped Apollo. The city became famous for its oracle (prophet). People of Athens looked to Athena as their protector. Ephesus became the center of the cult of Artemis. The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (see Seven Wonders of the Ancient World ).

Greek heroes

became almost as important as the divinities in Greek mythology. Heroes were largely or entirely mortal. They were born, grew old, and died. But they still associated with the divinities. Many heroes claimed gods as their ancestors.

Most Greek heroes and heroines can be divided into two main groups. The first group came before the Trojan War, and the second group fought in the war.

The most famous heroes before the Trojan War include Jason, Theseus, and Oedipus. Jason led a band of heroes called the Argonauts on a search for the fabulous Golden Fleece, the pure gold wool of a sacred ram. Theseus killed the Minotaur, a monster with the body of a man and the head of a bull. Oedipus, the king of Thebes, unknowingly killed his father and married his mother. Oedipus’s story has been popular with artists and writers for more than 2,000 years.

The Greek heroes in the Trojan War included Agamemnon, the commander in chief; Menelaus, Helen’s husband; and Odysseus (Ulysses in Latin), the clever general whose plan finally led to Troy’s defeat. Achilles was the most famous Greek warrior, and the major Trojan heroes were Hector and Paris. The gods and goddesses participated in the war almost as much as the heroes. Nearly all the divinities sided with the Greeks. The major exception was the goddess of love, Aphrodite.

Roman mythology

To many people, Roman mythology largely seems a copy of Greek mythology. The Romans came into contact with Greek culture during the 700’s B.C., and afterward some of their divinities began to reflect the qualities of Greek gods and goddesses. But before that time, the Romans had developed their own mythology. In fact, many of the basic similarities between Roman and Greek mythology can be traced to the common Indo-European heritage shared by Rome and Greece.

Roman divinities.

Before the Romans came into contact with Greek culture, they worshiped three major gods—Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. These gods are known as the archaic triad, meaning old group of three. Jupiter ruled as god of the heavens and came to be identified with Zeus. Mars was god of war. He occupied a much more important place in Roman mythology than did Ares, the war god in Greek mythology. Quirinus apparently represented the common people. The Greeks had no similar god.

By the late 500’s B.C., the Romans began to replace the archaic triad with the Capitoline triad—Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. The triad’s name came from the Capitoline Hill in Rome, on which stood the main temple of Jupiter. In the new triad, Jupiter remained the Romans’ chief god. The Romans identified Juno with the Greek goddess Hera and Minerva with Athena.

Between the 500’s and 100’s B.C., additional Roman mythological figures appeared, nearly all based on Greek divinities. These Roman divinities, with their Greek names in parentheses, included Bacchus (Dionysus), Ceres (Demeter), Diana (Artemis), Mercury (Hermes), Neptune (Poseidon), Pluto (Hades), Venus (Aphrodite), and Vulcan (Hephaestus).

In addition to Greek-inspired divinities, the Romans worshiped many local gods and goddesses. These included Faunus, a nature spirit; Februus, a god of the underworld; Pomona, goddess of fruits and trees; Terminus, god of boundaries; and Tiberinus, god of the Tiber River.

Romulus and Remus.

In their mythology, the Romans—unlike the Greeks—tried to explain the founding and history of their nation. Thus, the Romans came to consider their divinities as historical persons. The best example of this historical emphasis is the story of Romulus and Remus, the mythical founders of Rome.

The ancient Romans believed that Romulus and Remus were twins born of a mortal mother and the war god, Mars. Soon after their birth, they were set afloat in a basket on the Tiber River. A she-wolf found the babies and cared for them. Finally, a shepherd discovered the twins and raised them to adulthood.

Romulus and Remus decided to build a city at the spot on the Tiber where the wolf had found them. In a quarrel, Romulus or one of Romulus’s followers killed Remus. Romulus then founded Rome, supposedly in 753 B.C. The Romans believed that Romulus became the city’s first king and established most of the Roman political institutions.

The seven kings.

According to Roman mythology, Romulus was the first of seven kings who ruled Rome from its founding until the early 500’s B.C. The kings after Romulus were Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius, and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus. The seven kings became known for various achievements. For example, Numa started many of Rome’s basic religious institutions. Tullus was a warlike king who conquered the Albans, an Italian tribe that lived southeast of Rome.

There is little evidence that the seven early kings of Rome ever existed or that any of the events connected with their reigns took place. Some scholars believe these kings probably originated as divinities, whom the Romans converted into historical figures. The kings and the gods have many similarities. For example, Romulus resembles Jupiter because both were primarily rulers, not military leaders. Tullus resembles Mars.

The

During the 200’s B.C., the Romans tried to relate the origins of their divinities to Greek myths. About the time of the birth of Christ, the Roman poet Virgil wrote an epic poem called the Aeneid. Virgil modeled the Aeneid on the Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer. Virgil tried to connect the origins of Rome to the events that followed the fiery destruction of Troy by the Greeks.

The Aeneid traces the wanderings of the Trojan hero Aeneas, who escaped unharmed from the burning city. He stopped for a time in the city of Carthage in northern Africa. There, he rejected the love of Dido, queen of Carthage. He then sailed for Italy and, in time, landed near the mouth of the Tiber River. After many adventures, Aeneas founded a town. Aeneas’s son Ascanius later moved the town to Alba Longa, where Romulus and Remus were born. Virgil thus connected the founding of Rome with the Trojan War, a significant event in Greek mythology. See Aeneid.

Mythology of the Pacific Islands

Many thousands of islands lie scattered throughout the Pacific Ocean. A rich tradition of myths and mythological figures flourished among the numerous cultures of the islands until the late 1800’s, when many of the people became Christians. Some non-Christian cultures retain their traditional mythologies. Some Christians also have kept parts of their traditional mythologies. See Pacific Islands.

Creation myths of the Pacific Islands.

Some cultures of the Pacific Islands believed that heaven and the earth always existed. These cultures therefore developed no myths about the creation of the world. Many cultures also assumed that the ocean, which plays such a vital part in Pacific Islands life, always existed.

Some island cultures believed that gods created the world. Other cultures thought the world developed slowly from a great emptiness. According to this myth, the earth and the sky first existed close together and then separated. Several versions of the myth explain how this separation occurred. One example comes from the Māori people of New Zealand. Māori have a myth in which the sky, Rangi, loved the earth, Papa. Rangi and Papa gave birth to many gods, who became crushed in the embrace of their parents. To survive, the gods separated the earth and the sky, so that life could exist between them.

Pacific Islands divinities.

Many similarities existed among the major divinities of the Pacific Islands cultures. Many islanders worshiped a god called Tangaroa. In the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), he and another divinity ruled the world jointly. In Tahiti, he was a human being who became a divinity.

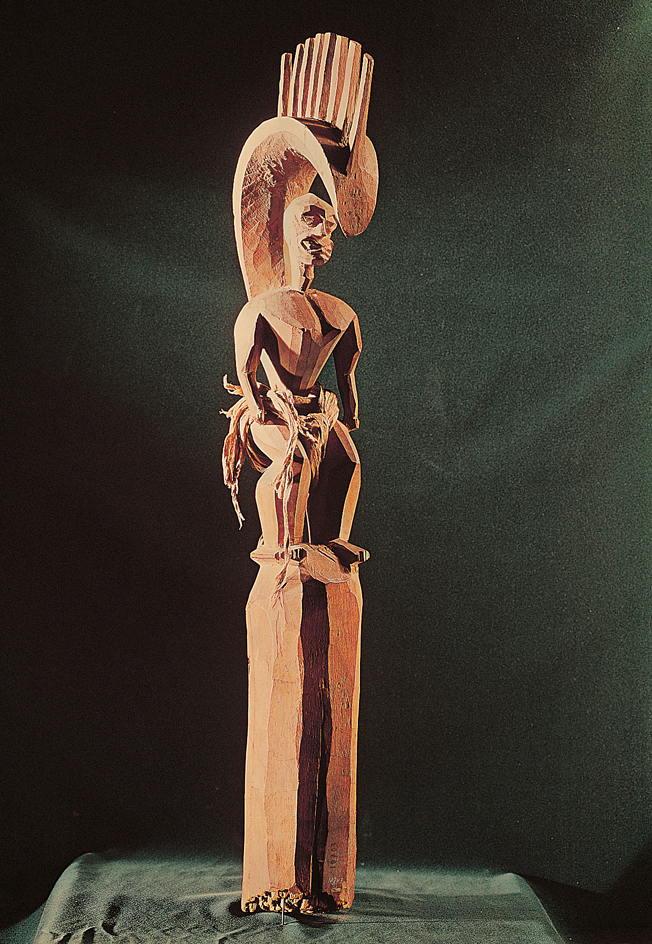

The most famous demigod among the islands of Polynesia was Maui. According to some myths, Maui created the Hawaiian Islands by fishing them up from the ocean. One of the Hawaiian Islands is named for him. The Polynesians also credited Maui with teaching human beings how to make fire and do other useful things.

The people of the Pacific Islands believed in the existence of little people similar to the dwarfs and elves of European folklore. The Hawaiians called these people the Menehune << meh neh HOO neh >> . Pacific Islanders believed the Menehune were responsible for events that could not otherwise be explained. For example, if a worker finished a job faster than expected, the Menehune got the credit for the worker’s unexplainable speed. If a wall was so old that nobody could remember who built it, the people decided the Menehune must have put it up.

Mana and taboo.

The idea of mana was important in Pacific Islands mythology. The islanders considered mana an impersonal, supernatural force that flowed through objects, persons, and places. A person who succeeded at a difficult task had a large amount of mana. However, a warrior’s defeat in battle showed that the warrior had lost mana. The islanders believed that certain animals, persons, and religious objects had so much mana that contact with them was dangerous for ordinary people. These mana-filled beings and objects were thus declared taboo (forbidden to touch). The islanders believed a person who touched a taboo object would suffer injury or even death. See Taboo.

Celtic mythology

The Celts were a diverse group of ancient peoples who shared a common language, religion, and culture. Their culture influenced most of northern and western Europe during the Iron Age, beginning about 700 B.C. From Europe, the Celts spread to England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. See Celts.

Much of our information on Celtic mythology concerns mythical characters and events in Ireland. During the Middle Ages, from about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s, Irish monks preserved many ancient Celtic myths in several collections of manuscripts. The most important collection of manuscripts is the Lebor Gabala (Book of Conquests), which traces the mythical history of Ireland. Another important collection of manuscripts, the Mabinogion << mahb ihn AWG ee uhn >> , comes from Wales. The first four stories in this collection are called the “Four Branches of the Mabinogi.” These stories describe the mythical history of Britain. The Welsh myths show a much stronger Christian influence than do the Irish myths. The Welsh myths also tend to emphasize human characters. The Irish myths deal more with divinities.

The Irish cycles.

A great deal of Irish Celtic mythology concerns three important cycles (series of related stories). These cycles are (1) the mythological cycle, (2) the Ulster cycle, and (3) the Fionn << fihn >> cycle.

The mythological cycle,

the oldest cycle, is preserved in the Lebor Gabala. The cycle describes the early settlement of Ireland through a succession of invasions by supernatural races. The most important race was the Tuatha Dé Danann << too AH hah day dah NAHN >> , or People of the Goddess Danu. The Tuatha De Danann defeated two other races, the Firbolgs << FEER buhl uhgz >> and the Fomorians << foh MAWR ee uhnz >> . The Tuatha De Danann were in turn defeated by the Sons of Mil, also called the Milesians. The Tuatha De Danann were the source of most of the divinities that the Irish people worshiped before Christianity arrived in the A.D. 400’s.

The Ulster cycle

centers on the court of King Conchobar << kahn KOH bahr >> at Ulster, probably about the time of Christ. The stories deal with the adventures of Cúchulainn << koo KUHL ihn >> , a great Irish hero who can also be considered a demigod. In some ways, he resembled the Greek hero Achilles. But unlike Achilles and other Greek heroes, Cuchulainn had many supernatural powers. For example, he could spit fire in battle. He was also a magician and poet.

Many stories about Cuchulainn appear in the Ulster cycle. Probably the best known is The Cattle Raid of Cooley. In this story, Queen Maeve of Connaught ordered a raid on Ulster to capture a famous brown bull. Cuchulainn single-handedly fought off the invaders until the queen’s forces finally captured the bull. However, the Ulster warriors led by King Conchobar came to Cuchulainn’s aid and drove the invaders out of the country. Queen Maeve plotted revenge against Cuchulainn and several years later used supernatural means to cause his death. See Cuchulainn .

The Fionn cycle,

also known as the Fenian cycle, describes the deeds of the hero Finn MacCool and his band of warriors, known as the Fianna. Finn and the Fianna were famous for their great size and strength. In addition, Finn was known for his generosity and wisdom. Although divine beings and supernatural events play a part in these stories, the central characters are human. Some scholars believe the events in the Fionn cycle may reflect the political and social conditions in Ireland during the A.D. 200’s.

The most famous story in the Fionn cycle is “The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Grainne.” In this story, Finn was to marry Gráinne << GRAWN yuh >> , the daughter of an Irish king. However, she fell in love with Diarmuid << DEER mihd >> , Finn’s friend and nephew, and persuaded Diarmuid to elope with her. Finn and his warriors pursued the lovers. Much of the story concerns the adventures of Diarmuid and Grainne as they fled. Finally, Finn caught Diarmuid and Grainne and indirectly caused the death of Diarmuid. At first, Grainne hated Finn, but he courted her until she became his wife. See Finn MacCool .

Welsh myths.

Two races of divinities appear in Welsh mythology—the Children of Don and the Children of Llyr << leer >> . Both races partly resemble the Tuatha De Danann in Irish mythology, possibly because the myths were carried from Britain to Ireland as the Celtic culture spread westward.

The most famous Welsh myths concern King Arthur and his knights. The mythical King Arthur was probably based on a powerful Celtic chief who lived in Wales during the A.D. 500’s. Some stories about Arthur and his knights can be traced to such early Welsh literature as the “Four Branches of the Mabinogi.” One of these stories tells of the knights’ search for the Holy Grail, the cup Christ used at the Last Supper. Some scholars say the Christian myth of the Holy Grail originated in this story.

Teutonic mythology

Teutonic mythology consists of the myths of Scandinavia and Germany. It is sometimes called Norse mythology, after the Norse people who lived in Scandinavia during the Middle Ages. The basic sources for Teutonic mythology are two works called Eddas. They were oral poems that were written down in the 1200’s (see Edda ). Other information on Teutonic mythology comes from legends about specific families and heroes and from German literary and historical works.

The creation of life.

According to the Eddas, two places existed before the creation of life—Muspellsheim, a land of fire, and Niflheim, a land of ice and mist. Between them lay Ginnungagap << gihn NAWNG ah gahp >> , a great emptiness where heat and ice met. Out of this emptiness came Ymir << EE mihr >> , a young giant and the first living thing. A second creature soon appeared, a cow named Audumla << aw DOOM lah >> .. Ymir lived on Audumla’s milk. As Ymir matured, he gave birth to three beings. He bore them from his armpits and from one leg. A divine race of giants was thus born.

Meanwhile, a second giant, Buri, was frozen in the ice of Niflheim. Audumla licked the ice off his body, freeing him. Buri created a son named Bor, who married the giantess Bestla. They had three sons—Odin, Ve << vay >> , and Vili << VIHL ee >> . The sons founded the first race of gods.

The construction of the world.

After Odin became an adult, he led his brothers in an attack on the giant Ymir and killed him. Odin then became supreme ruler of the world. The gods defeated the giants in battle, but the giants planned revenge on their conquerors.

Odin and his brothers constructed the world from Ymir’s body. Ymir’s blood became the oceans, his ribs the mountains, and his flesh the earth. The gods created the first man from an ash tree and the first woman from an elm tree. They also constructed Asgard, which became their heavenly home. Valhalla, a great hall in Asgard, was the home of warriors killed in battle.

Many divinities lived in Asgard. These divinities were called the Aesir << EYE seer >> , much like the leading Greek gods and goddesses were called the Olympians. The ruler of Asgard was Odin. Thor, Odin’s oldest son, was god of thunder and lightning. Balder, another of Odin’s sons, was god of goodness and harmony. Other divinities included Bragi, the god of poetry, and Loki, the evil son of a giant. The most important goddesses included Frigg, Odin’s wife; Freyja, goddess of love and beauty; and Hel, goddess of the underworld.

A giant ash tree known as Yggdrasil << IHG drah sihl >> supported all creation. In most accounts of Yggdrasil, the tree had three roots. One root reached into Niflheim. Another grew to Asgard. The third extended to Jotunheim, the land of the giants. Three sisters called Norns lived around the base of the tree. They controlled the past, present, and future. A giant serpent called Nidhoggr << neeth HOH guhr >> lived near the root in Niflheim. The serpent was loyal to the race of giants defeated by Odin. It continually gnawed at the root to bring the tree down, and the gods with it.

Teutonic heroes.

Sigurd the Dragon Slayer probably ranks as the most important hero in Teutonic mythology. He appears in a Scandinavian version of German myths about a royal family called the Volsungs. Sigurd became the model for the mythical German hero Siegfried, who appears in the Nibelungenlied, a famous German epic of the Middle Ages. Other heroes in Teutonic mythology include Starkad, who was a mortal friend of Odin’s, and the Danish warrior Hadding. See Nibelungenlied .

The end of the world.

Unlike many other major Western mythologies, Teutonic mythology includes an eschatology (account of the end of the world). According to Teutonic mythology, there will be a great battle called Ragnarok. This battle will be fought between the giants, led by Loki, and the gods and goddesses living in Asgard. All the gods, goddesses, and giants in the battle will be killed, and the earth will be destroyed by fire. After the battle, Balder will be reborn. With several sons of dead gods, he will form a new race of divinities. The human race will also be re-created. During Ragnarok, a man and woman will take refuge in a forest and sleep through the battle. After the earth again becomes fertile, the couple will awake and begin the new race of human beings. The new world, cleansed of evil and treachery, will endure forever.

Aztec mythology

The Aztec Indians of central Mexico developed one of the most interesting mythologies in the Americas. The Aztec established a highly advanced civilization that lasted from the A.D. 1300’s until it was conquered by the Spanish in 1521. Advanced cultures, such as the Toltec and Maya, had existed in Mexico before the Aztec came to power. The Aztec borrowed many of their divinities from these earlier Indian cultures. In addition, the Aztec conquered many of the neighboring Indian peoples. As these peoples became part of the Aztec Empire, many of their divinities became part of the Aztec mythology. The Aztec thus developed a complicated mythology, composed of gods of earlier Indian civilizations, their own gods, and gods of the peoples they had conquered.

The Aztec believed the universe had passed through four ages called suns and that they were living in the fifth sun. The gods had ended each previous sun with a worldwide disaster and then created a new world. At the end of the first sun, the world was destroyed by jaguars. At the end of the second sun, a hurricane destroyed the earth. At the end of the third sun, fire rained from the sky and destroyed the world. At the end of the fourth sun, the world ended with a flood. The Aztec believed they were living in the fifth sun and that the world would end with an earthquake.

The chief Aztec divinity was probably the war god, Huitzilopochtli << wee tsee loh PAHCH tlee >> . The Aztec worshiped Tezcatlipoca << tehs kah tlee POH kah >> , a sun god, under four forms, each identified with a specific color and direction. Almost every Indian civilization in Mexico worshiped the god Quetzalcoatl << keht sahl koh WAH tuhl >> . The Aztec associated him with the arts. Tláloc, the rain god, was probably the oldest god in Aztec mythology. His wife or sister, Chalchiuhtlicue << chahl chee wee TLEE kwah >> , was goddess of running water. She protected newborn children, marriage, and innocent love. Tlazoltéotl << tlah soh TEE ah tuhl >> was goddess of pleasure and guilty love. Farming was the basis of the Aztec economy, and so the people worshiped many agricultural divinities. The most important of these gods included Centéotl << sehn tay AHT uhl >> , the maize god; Chicomecóatl << chee koh may koh AHT uhl >> , the goddess of agricultural abundance; and Xipe Totec << SHEE pay TOH tehk >> , the god of vegetation.

In Aztec mythology, souls of the dead lived in separate places, depending on how death occurred. For example, a place called Tonatiuhichan << toh nah tee uh wee CHAHN >> was reserved for warriors and victims of religious sacrifices. Other places were reserved for people who had drowned or for women who had died in childbirth. Most souls passed to Mictlan, an underworld ruled by Mictlantecuhtli << mihk tlahn tay KUHT lee >> and his wife, Mictlancihuatl << mihk tlahn see KWAH tuhl >> .

Human sacrifice played an important role in Aztec religion. The Aztec held great ceremonies and festivals, during which they offered human hearts to Huitzilopochtli and the other major divinities. The Aztec slashed open the chests of their sacrificial victims and tore out their hearts. Most of the victims were prisoners of war. The Aztec considered the victims as representatives of the gods themselves. During the period up to their deaths, some victims were dressed in rich clothing, given many servants, and treated with great honor. The Aztec believed that the souls of the sacrificial victims flew immediately to Tonatiuhichan and lived there forever in happiness.

The study of myths

For more than 2,500 years, scholars have sought to understand myths. Some experts think that early people created myths to explain things that they could not understand, including natural occurrences, such as earthquakes and storms, and celestial phenomena, such as comets and eclipses. Other scholars theorize that myths are a form of philosophy, created to give shape to abstract ideas and to comment on morals and the human condition. Some scholars have investigated myths as a window into the hidden structures of language, culture, and the human mind. Still others view myths as the foundation of all literature, examining myths for basic literary themes and characters.

The imaginative power of myths can be seen in the rich variety of approaches to their study. No single scholarly approach fully explains what myths are or how they function in societies. Yet, each approach contributes to our overall understanding of mythology.

Allegorical approaches.

The formal study of myths began as a part of Greek philosophy. Early Greek philosophers were concerned with fundamental questions about the origin, nature, and purpose of the universe and of human beings. They sought rational, logically consistent answers to such questions and often rejected myths as mere stories. The early Greek philosophers tended to view myths as allegories. An allegory is a story with both a literal and a symbolic meaning. Objects, persons, and events in an allegory serve as symbols with meanings outside the story being told. Greek scholars thus examined myths to find symbolic references to natural occurrences, historical events, philosophical principles, or religious truth.

One of the earliest allegorical theories about myths was developed by Euhemerus of Messene, a Greek scholar who lived during the late 300’s and early 200’s B.C. He believed that myths originated as historical facts about actual persons and events. These stories became exaggerated and romanticized as people told and retold them over time. In his main work, Sacred History, Euhemerus claimed to have discovered inscriptions proving that the gods Kronos and Zeus were based on historical kings. Modern scholars usually lack enough historical evidence to determine whether a mythical figure ever existed. However, archaeologists occasionally discover evidence that a few myths have some basis in historical fact. For example, many experts believe that a site near Hisarlik, Turkey, includes the remains of the historical city of Troy described in Homer’s Iliad.

Myths were also viewed as allegories by the Stoic philosophers, who flourished in Greece and Rome from about 300 B.C. to A.D. 300. Rather than seeing myths as distorted history, however, the Stoics viewed myths as dramatizations of moral truth. To the Stoics, the gods in myths represented certain abstract qualities. For example, Athena embodied wisdom; Ares represented courage; and Aphrodite symbolized desire. Stoic scholars interpreted Greek myths to show how human affairs were influenced by powerful forces of desire, hatred, courage, and wisdom.

Later, Christian scholars borrowed this method, claiming that Greek and Roman myths were allegories of church teachings. Throughout the Middle Ages, teachers used handbooks featuring brief summaries of Greek and Roman myths to illustrate Christian moral lessons.

Comparative approaches.

In the 1700’s, European linguists made detailed comparisons of the languages of India, the Middle East, and Europe. They concluded that the similarities among these languages could only be explained by the existence of a common source language. Today, this presumed ancestor language is referred to as Proto-Indo-European. Linguists have since demonstrated that most languages spoken from India to Europe descended from this original source. Such studies inspired scholars to apply the same method to the study of myths.

In the 1800’s, two German language scholars, Franz Felix Adalbert Kuhn and Friedrich Max Müller, helped develop what became known as the Nature School in the study of mythology. These scholars combined the methods of comparative linguistics—the study of language as it varies from place to place and over time—with the allegorical approach. They collected texts of myths from around the world. By observing a number of recurrent themes in all myths, they concluded that the myths must have descended from a small handful of original ancestor myths. They also reasoned that these original stories were inspired by ancient people’s fear of natural occurrences.

Kuhn theorized that the world’s myths descended from a single original story that described a division between earth and sky. The story included a heroic character who traveled between these two realms, stealing a life-giving force from the gods and bestowing it upon human beings. The Greek myth of Prometheus is the best-known example of this type of story, but there are many others around the world (see Prometheus ). Kuhn saw this myth and its many variants as allegories of a rainstorm, which bestows rain and fire (in the form of lightning) from the heavens, making all life possible.

Müller proposed that all myths could be understood as reflecting ancient people’s fascination with the movements of the sun throughout the year. His theory, called the Solar Hypothesis, suggested that poetic descriptions of weather events, such as the sunrise or a thunderstorm, became distorted into the wide variety of deities, rituals, and superstitions found in myths of the world.

Two German brothers, Jakob Ludwig Grimm and Wilhelm Karl Grimm, collected folk tales from peasants in Germany from 1807 to 1814. The stories they collected became famous as Grimm’s Fairy Tales. The Grimms realized that similar versions of their tales existed throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. They identified common themes that probably existed in the ancestral tales. Such themes include divinities that embodied various ideas—such as death, war, and desire—or natural forces—such as the sun, moon, earth, and weather. Other common themes include the world being destroyed by a great flood and the death and resurrection of a divine character to explain the changing seasons and the return of life to the land each spring. Today, scholars continue to use the comparative approach to learn what can be revealed about different cultures by variations among myths.

Anthropological approaches.

The scholars who developed comparative approaches largely studied ancient texts in libraries, viewing myths as survivals from a distant past. Around 1870, in contrast, anthropologists began to investigate the functions of myths in living societies and their members.

By 1871, the English anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor proposed a theory to describe how European society evolved (transformed gradually) from a society thought to be backward and superstitious to the sophisticated and rational world in which he lived. Tylor believed that ancient people developed the concept of a soul and of spirits to explain dreams, visions, apparitions, and death. Later, he reasoned, people began to identify these spirits with various sacred places and material objects. This idea gave rise to the belief that all things in nature have souls, a belief now referred to as animism (see Animism ). Tylor considered animism the first step in the development of human thought—and the basis of myths.

According to Tylor, as societies continued to evolve, various spirits became associated with abstract moral qualities, such as good and evil. These associations fostered the primitive belief that gods reward those who are good and punish those who are evil. Tylor believed that from these ideas and the myths associated with them, all human cultures would eventually develop into societies where reason, ethics, and the rule of law shape human behavior.

Other anthropologists modified Tylor’s evolutionary model. As they collected detailed information about the religious practices, beliefs, and myths of the peoples they studied, the emphasis shifted away from the idea that all cultures evolve through a common set of stages. Instead, anthropologists undertook a more general examination of the differences between civilized societies and isolated, nonindustrial societies.

In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, the Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer developed important new ideas about myths. He began by trying to explain an ancient Italian ritual conducted at Nemi, near Rome. At Nemi, there was a sacred grove of trees. In the grove grew a huge oak tree associated with the goddess Diana. A priest presided over the grove and the oak tree. The process by which priests were replaced aroused Frazer’s curiosity and interest. To become the priest, a man had to kill the current priest with a branch taken from the tree, a “golden bough.” If the man succeeded, he proved that he had more vigor than the presiding priest and thus had earned the position. To explain how this unusual ritual arose and what it represented, Frazer searched myths from around the world for evidence of similar rituals.

Frazer’s study of the Nemi ritual developed into one of the most ambitious anthropological works on myths ever attempted, The Golden Bough (1890). In his study, Frazer saw a progression from simple magical rituals and beliefs to increasingly abstract forms of religious belief. He concluded that the Nemi ritual descended from much older and simpler rituals. Frazer presumed that strong, virile young men were the embodiment of the powers of fertility. In early societies, Frazer reasoned, priestly figures were ritually killed at the end of a term—or when their powers appeared to fail—and replaced by younger, more virile men. In this way, the vital force of the world was periodically renewed through a magically symbolic act. Frazer wrote that societies throughout the world sacrificed symbols of their gods to keep these gods—and thus the world—from decaying and dying. According to Frazer, this theme of the dying and reborn god appears in almost every ancient mythology, either directly or symbolically.

Bronisław Malinowski, a Polish-born British anthropologist of the early 1900’s, disagreed with Tylor’s and Frazer’s methods, although he shared their assumptions that societies evolve. Tylor and Frazer studied ancient texts. The two scholars often began with certain beliefs about culture and myths and then collected and reported data that supported their theories. In contrast, Malinowski emphasized fieldwork (studying other cultures through direct experience) to learn how myths function in living societies. He pointed out that field researchers could observe myths in the form of rituals and ceremonies. In the course of such fieldwork, Malinowski saw that myths serve as powerful expressions of religious ideas that affect every aspect of a society. Malinowski’s ideas have greatly influenced how anthropologists study myths. Today, the anthropological approach to myths continues to focus on how myths circulate in living societies, how they create and reinforce social customs, and how they influence the beliefs and behaviors of living people.

Psychological approaches

to the study of myths began with Sigmund Freud, an Austrian physician of the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Freud revolutionized ideas on how the human mind works. He established the theory that unconscious motives control much behavior. Freud divided the mind into three parts: (1) the id, (2) the ego, and (3) the superego. The id is the source of the most basic instincts. According to Freud, the id is the largest and most powerful aspect of mind, but it functions below the level of conscious awareness. The ego governs such areas as memory, voluntary movement, and decision making. The superego is a person’s conscience. It distinguishes right from wrong.

Freud believed that behind the literal surface of a myth lay hidden its true psychological meaning. His most important writings include The Interpretation of Dreams (1900), a work that examines dreams and also myths. Freud believed that the unconscious id is the true reality of the human mind. However, he believed the conscious mind censors the thoughts and impulses of the id because they are too dangerous to be recognized or acted upon. Freud considered dreams and myths as a way for the conscious mind to make understandable and safe the unconscious forces and conflicts of the id.

In the early 1900’s, the Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung, a student of Freud’s, developed a theory about how myths reflect a person’s attitudes and behavior. Freud believed that the unconscious mind served as a storage vessel for an individual’s repressed or forgotten thoughts, memories, and experiences. Jung suggested that everyone has both a personal unconscious and a collective unconscious. The personal unconscious is formed by the person’s experiences in the world as filtered through the senses. The collective unconscious is inherited and shared by all humankind.

Jung believed that the collective unconscious is organized into basic patterns that are represented in universal symbols, which he called archetypes. Jung believed that all mythologies have certain archetypes in common. He recognized such archetypes as the Miracle Child, the Wise Man, or the Unrelenting Father that often appear in myths in the form of such characters as gods and heroes. Other archetypes, such as the number four, lovers, or death by water, may appear as mythic themes, such as love or revenge, or the struggle for a throne. Likewise, certain archetypal places appear in myths throughout the world, such as a joyous home of the gods or a dismal underworld. Jung argued that these universal archetypes in myths stem from the collective unconscious, which is shared by human beings in every culture.

Literary approaches.

Toward the end of the 1800’s, many scholars began to apply methods of literary study to the study of mythology. In doing so, they developed a range of concepts for discussing myths in terms of literary characters, plots, symbols, and meaning. They also used ideas from other fields of study. Literary scholars emphasize that myths are stories, with unique features, narrative logic, appealing characters, vivid images, and powerful symbols. Myths, like all literature, can be enjoyed both for their entertainment value and for the insights they provide about human nature.

The American Joseph Campbell remains the best-known scholar in the literary study of myths. Both Freud and Jung influenced his work. In his book Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell examined myths from around the world. He noticed that many myths tell of an individual, usually a man, who leaves the ordinary world and enters the supernatural world. There he learns of his heroic destiny and receives charms or magical weapons. The man defeats the forces that oppose him and returns to the society from which he came with new knowledge and new powers. Campbell called this type of story the monomyth. Versions of the monomyth can be found in nearly every culture.

For Campbell, the hero’s story was more than an exciting tale of adventure. He believed that the monomyth expressed a universal life pattern through which all people can gain a sense of spiritual and social purpose.

Other important scholars who took a literary approach to the study of myths include Robert Graves, an English author, and Northrop Frye, a Canadian literary and social critic. Graves wrote The White Goddess (1948), a study of myths and the source of poetry in mythology. He also wrote The Greek Myths (1958), a two-volume collection of Greek mythology. In these works, he demonstrated how literary approaches can make ancient myths relevant to modern concerns. Frye developed his theory of literary criticism from his reading of classical Greek and Roman mythology and the Bible. In his most important book, Anatomy of Criticism (1957), Frye pointed out that all works of literature incorporate similar basic structures. He argued that myths are central to all societies and, therefore, to all literature.

Structuralist approaches.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, a French anthropologist, introduced another important approach to myths. He developed a method called structuralism used in the study of human culture. Lévi-Strauss examined the structural similarities among myths, rather than focusing on particular characters and events. According to Lévi-Strauss, myths of different cultures may appear to be different. But if they have the same structure, they may actually express the same idea.

Using ideas derived from linguistics, Lévi-Strauss argued that myths are composed of fundamental units that fit together according to certain rules. He called these basic units mythemes. He thought that mythemes are related to each other in contrasting pairs called binary oppositions. For example, when one hears the word black, one cannot help but also think of the opposite, white. Lévi-Strauss argued that the tension between binary oppositions imparts structure to myths.

Lévi-Strauss found patterns in binary oppositions that link the myths of all cultures. The binary opposition between natives and foreigners, for example, is found in many important myths. For example, the Greeks in the Iliad are foreigners on Trojan soil. The main characters of the Odyssey and the Aeneid are also wanderers who discover the deepest truths about themselves in foreign lands.

Lévi-Strauss’s most important work is his four-volume study of myths, Mythologiques (1964-1971). The first volume, Le Cru et le cuit (The Raw and the Cooked), begins with a single myth of the Bororo people of Brazil. From it, Lévi-Strauss goes on to examine nearly 200 myths from a variety of Native American cultures. He reduces these stories to their various mythemes and identifies the binary oppositions that exist among these myths.

One of Lévi-Strauss’s insights was that both individuals and societies instinctively seek to resolve the binary oppositions that occur in life. According to Lévi-Strauss, myths are important means to resolve these stark contradictions. He argued that the deep structures of myths are always present, regardless of plot, character, setting, and culture, and that these deep structures “speak themselves” through flesh-and-blood human beings in the form of various stories, legends, and myths.

Combined approaches.

Today, scholars specializing in the study of myths often combine different approaches to examine various aspects of myths. Modern scholars realize that there is no single or correct answer to the question of why myths have such enduring appeal. These seemingly simple stories will remain mysterious sources of spiritual inspiration, intellectual curiosity, and insight into the human condition for as long as there are people to read them and scholars to study them.