Adams, John Quincy (1767-1848), was the first son of a president of the United States to also become president. The second was George W. Bush, who became president in 2001. John Quincy Adams, like his father, John Adams, failed to win a second term. But soon afterward, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. This pleased him more, he said, than his election as president.

Before entering the presidency, Adams held several important diplomatic posts. He took part in the negotiations that ended the War of 1812. As secretary of state, he helped develop the Monroe Doctrine. Quarrels within his party hampered Adams as president, and he made little progress with his ambitious legislative program. His years in the White House were perhaps the unhappiest period of Adams’s life.

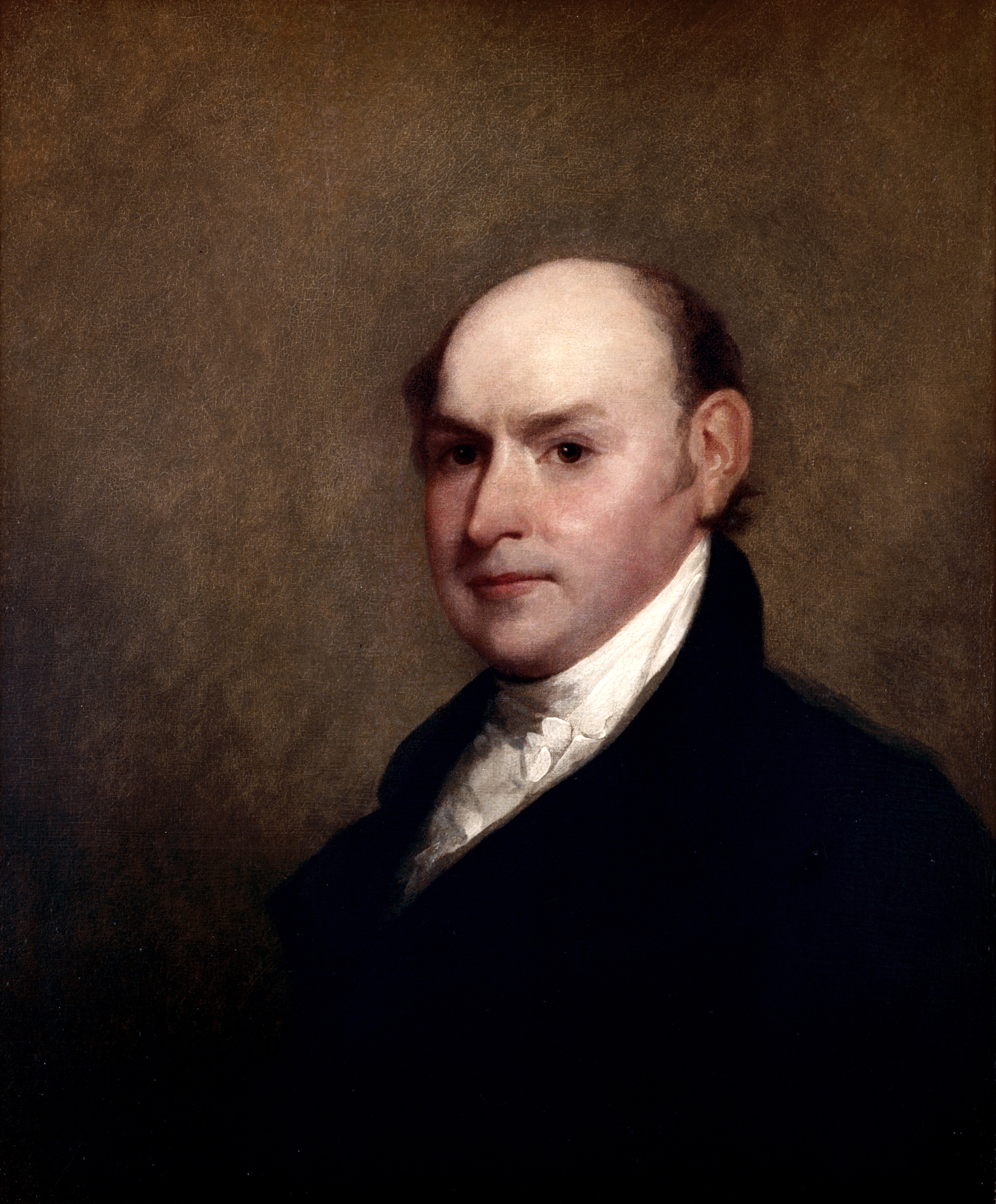

Adams was short and stout, and his shrill voice often broke when he became excited. Yet he spoke so well that he was nicknamed “Old Man Eloquent.” Adams was affectionate with close friends, but more reserved toward others. He once referred to himself as “an unsocial savage.”

During Adams’s administration, Noah Webster brought out his two-volume American Dictionary of the English Language, and James Fenimore Cooper published his famous novel The Last of the Mohicans. The American labor movement began in Philadelphia.

Early life

Childhood.

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, in the family home in Braintree (now Quincy), Massachusetts. He was the second child and eldest son of the second president of the United States. During the 1770’s, his father was away much of the time serving in the Continental Congresses. John Quincy had to help his mother manage a large farm. In February 1778, Congress sent his father to France. John Quincy, although not yet 11, pleaded to go along on the dangerous voyage. His father proudly wrote in his diary: “Mr. Johnny’s behavior gave me a satisfaction I cannot express. Fully sensible of our danger, he was constantly endeavoring to bear it with a manly patience, very attentive to me, and his thoughts constantly running in a serious vein.”

Education.

Adams attended schools in Paris, Amsterdam, and Leiden as his father moved from one diplomatic assignment to another. At 14, he went to St. Petersburg as private secretary to Francis Dana, the first American minister to Russia. The boy rejoined his father in 1783 and served as his private secretary.

When the elder Adams became minister to the United Kingdom in 1785, young John returned home and entered Harvard College. He said later: “By remaining much longer in Europe I saw the danger of an alienation from my own country.” His previous studies enabled him to join the junior class at Harvard, and he graduated in 1787.

Lawyer and writer.

Adams read law for three years and began his own practice in 1790. But he had few clients and soon turned to political journalism.

In 1791, Thomas Paine published the first part of Rights of Man. Adams considered Paine’s ideas too radical and replied with 11 articles that he signed with the name “Publicola.” A second series, signed “Marcellus,” defended President George Washington’s policy of neutrality. A third series, signed “Columbus,” attacked French minister Edmond Genet, who wanted America to join France in a war against the United Kingdom.

Political and public career

Diplomat.

In 1794, Washington appointed Adams minister to the Netherlands. The French invaded the country three days after Adams arrived and overthrew the Dutch Republic. On a special assignment in London, Adams met his future wife, Louisa Catherine Johnson (Feb. 12, 1775-May 15, 1852), the daughter of a merchant who became the American consul general to London.

In 1796, Washington appointed Adams minister to Portugal. Just before he left for Lisbon, his father was elected president. Both men felt it would be undesirable for the son to hold such a post during his father’s administration. But Washington urged that the younger Adams stay on, calling him “the most valuable public character now abroad.” President Adams followed this recommendation and named his son minister to Prussia.

Adams’s family.

John Quincy married Louisa Catherine in 1797, just before leaving for Berlin. He served there more than four years. Adams and his wife had four children. Their only daughter, Louisa Catherine, died in infancy. George Washington Adams, the eldest son, died in 1829, at the close of his father’s presidency. John, who was named for his grandfather, died five years later. The youngest son, Charles Francis, served as minister to the United Kingdom during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

U.S. senator.

Thomas Jefferson became president in 1801. John Quincy Adams soon returned home, and he was elected to the Massachusetts Senate in 1802. Adams soon displayed the independence that marked his entire career. Fisher Ames, the Federalist leader in Massachusetts, described him as “too unmanageable.”

In 1803, the Federalists chose Adams to fill a vacant seat in the United States Senate. Although a Federalist, he often voted with the Democratic-Republicans. He broke with his party completely in 1807, when Congress passed the Embargo Act. The Federalists in New England wanted to trade with the British, but Adams supported the embargo, believing that it benefited the nation as a whole.

Federalist leaders in Massachusetts felt that Adams had betrayed them. They elected another man to his Senate seat several months before the 1808 elections. Adams resigned immediately and prepared for a career as professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard.

Again a diplomat.

Adams intended to stay out of public life permanently. But in 1809, President James Madison persuaded him to accept an appointment as minister to Russia. From mid-1814 to early 1815, Adams served as one of the American commissioners who negotiated the Treaty of Ghent with the British, ending the War of 1812. The negotiations gained respect for the United States, as well as for Adams as a diplomat.

Madison next appointed Adams as minister to the United Kingdom, a post once held by his father. While in London, Adams began discussions that led to improved relations along the U.S.-Canadian border. The United Kingdom and the United States agreed to stop using forts and warships in the Great Lakes region, leaving the frontiers of the two countries unguarded and open.

Secretary of state.

In 1817, President James Monroe called Adams home to serve as secretary of state. Adams made an agreement with the United Kingdom for joint occupation of the Oregon region. He negotiated a treaty that quieted Spanish claims to territory in the northwest and also acquired Florida. But his most important achievement as secretary of state was to help develop the Monroe Doctrine.

Austria, Prussia, and Russia had formed the Holy Alliance in 1815, after the fall of Napoleon. During and after the Napoleonic Wars, the countries of Central and South America had revolted against Spanish rule. When King Ferdinand VII regained the Spanish throne in 1823, many people feared that the Holy Alliance might help Spain reconquer its former colonies. British Foreign Minister George Canning asked the United States to join in a declaration against any such move. But Adams insisted that the United States should make its own policy. He declared that America must not “come in as a cockboat (small rowboat) in the wake of the British man-of-war.”

Adams made the first declaration of this policy in July 1823. He told the Russian minister that “the American continents are no longer subjects for any new European colonial establishments.” President Monroe followed Adams’s advice, and the Monroe Doctrine became a part of U.S. foreign policy. See Monroe Doctrine.

Election of 1824.

Many Americans believed Adams should follow Monroe as president. Both Madison and Monroe became president after serving as secretary of state. Adams felt he also should be elected but did little to attract votes. Three Democratic-Republicans opposed him: Henry Clay, William H. Crawford, and Andrew Jackson. John C. Calhoun was the running mate for both Adams and Jackson, and was elected vice president. Crawford, the secretary of the treasury, had appeared to be the leading candidate, but he suffered a stroke during the campaign. Jackson received 99 electoral votes; Adams, 84; Crawford, 41; and Clay, 37. None had a majority, so the House of Representatives had to choose one of the first three men. Clay, the speaker of the House, then threw his support to Adams, who was elected in February 1825.

Adams’s administration (1825-1829)

Democratic-Republican Party split.

Even before the House elected Adams, followers of Jackson accused Adams of promising Clay a Cabinet post in return for his support. When Adams named Clay secretary of state, Jackson’s powerful supporters charged that the two men had made a “corrupt bargain.” This split the Democratic-Republican Party, and Adams’s group became known as the National Republicans. Jackson’s group fought Adams for the next four years.

Rebuff by Congress.

Adams delivered his inaugural address in the Senate chamber of the unfinished Capitol. In this address, and in his first message to Congress, he recommended an ambitious program of national improvements. This program included the construction of highways, canals, weather stations, and a national university. He argued that if Congress did not use the powers of government for the benefit of all the people, it “would be treachery to the most sacred of trusts.” But the majority in Congress disagreed. Adams’s hopes for a partnership of government and science were not to be realized until after his lifetime.

The “tariff of abominations.”

By 1828, manufacturing had replaced farming as the chief activity in most New England states. These states favored high tariffs on imported goods. But high tariffs would make farmers in the South pay more for imported products. Southern leaders wanted a low tariff or free trade.

Jackson’s supporters in Congress wrote a tariff bill that put high duties on manufactured goods. They hoped to make the duties so high that even New Englanders would oppose the bill. To everyone’s surprise, enough New Englanders voted for the bill to pass it. The “tariff of abominations,” as it became known, aroused bitter anger in the South.

Life in the White House.

Adams threw all his energies into the presidency from the day he took office. Each day, he conferred with a steady procession of congressmen and department heads in his upstairs study in the White House. The president wrote in his diary: “I can scarcely conceive a more harassing, wearying, teasing condition of existence.” He felt a lack of exercise, in spite of daily walks. In warm weather, Adams liked to swim in the Potomac River.

Mrs. Adams suffered ill health during her husband’s term as president, but she overcame her sickness to serve as White House hostess. She was responsible for a brilliant series of parties during the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1825.

Election of 1828.

Adams had never been popular, chiefly because of his aloof manner. He had not even tried to defend himself against the attacks of Jackson and his followers, feeling it was below the dignity of the president to engage in political debate. At the same time, Jackson gained great popularity. In the election of 1828, Jackson won a popular vote proportionately larger than any other presidential candidate received during the rest of the 1800’s. He and his running mate, Vice President Calhoun, won 178 electoral votes. Adams and Secretary of the Treasury Richard Rush had 83.

Back to Congress

Election to the House.

Adams then retired to the family home in Quincy. But the people of Quincy asked him to run for Congress in 1830. He defeated two other candidates by large majorities and wrote in his diary: “My election as president of the United States was not half so gratifying.” He took his seat in the House of Representatives in 1831 and served for 17 years.

Adams served at times as chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee and of the Committee on Manufactures. But he remained independent of party politics. He fought President Jackson’s opposition to the second Bank of the United States. He also opposed Jackson’s policy of recognizing the independence of Texas. But Adams supported Jackson’s foreign policy and stern resistance to nullification (see Nullification ).

The Gag Rules.

Adams’s greatest public role may have occurred during debates about slavery. Abolitionists sent many petitions to Congress urging that slavery be abolished in the District of Columbia and in new territories. These petitions took much of the lawmakers’ time. In 1836, the House adopted the first of a series of resolutions called the Gag Rules to keep the petitions from being read on the floor. Adams believed these rules violated the constitutional rights of free speech and petition. He was strongly criticized in the House for opposing the Gag Rules, but he finally succeeded in having them abolished in 1844.

Adams became the first congressman to assert the right of the government to free slaves during time of war. President Abraham Lincoln based the Emancipation Proclamation on Adams’s arguments.

The Amistad Rebellion.

In 1841, Adams again publicly showed his opposition to slavery when he defended the Amistad rebels before the Supreme Court of the United States. The rebels were black Africans who had been captured and enslaved by whites. In 1839, they attacked their captors while on a ship called La Amistad in the Caribbean Sea. They killed two whites and took control of the vessel. They were later arrested in the United States for the killings and mutiny. Their case ended up in the Supreme Court. There, Adams strongly defended the rebels, arguing that every person has the right to freedom. The rebels were found not guilty. For more details, see Amistad Rebellion.

Death.

On Feb. 21, 1848, he suffered a stroke at his House desk. Too ill to be moved from the building, he was carried to the Speaker’s room. He died there two days later. Adams was buried in the churchyard of the First Unitarian Church in Quincy, Massachusetts. His wife died on May 15, 1852, and was buried at his side. Their remains were later moved to the church crypt.