Babylonia was an ancient region in what is now southern Iraq. It was bounded roughly by the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the Persian Gulf, and the ancient city of Babylon, which stood about 60 miles (97 kilometers) south of present-day Baghdad, Iraq. From 2000 B.C. to the 200’s B.C., Babylonia was the site of several kingdoms and empires ruled by dynasties (series of rulers from one family).

The Babylonians continued the political and cultural forms developed by the Sumerian civilization, which had begun about 3500 B.C. in southern Mesopotamia (now southeastern Iraq). They produced law codes, mathematical studies, astronomical observations, and literary works in cuneiform, a Sumerian writing system. Great leaders of Babylonia included Hammurabi, Nebuchadnezzar II, and Alexander the Great.

Way of life

Babylonians lived in cities and villages, and in tribal groups. Scholars know the most about urban society, which was based on membership in great households (palaces and temples) and private households. An elite group of wealthy city dwellers headed the various households. They included government officials, priests, large landowners, and some traders. Clerks, craftworkers, and other skilled workers made up a small class of commoners. Slaves, village farmers, and animal herders belonged to the lowest class.

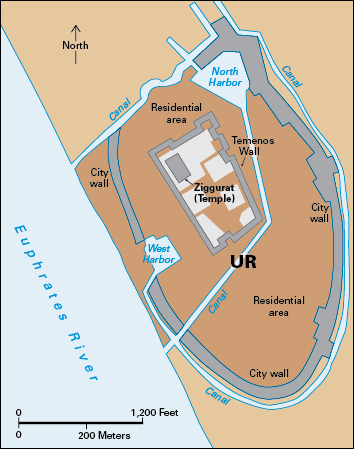

The Babylonian economy depended chiefly on grain farming. Farmers also cultivated fruits and vegetables. The people consumed some dairy products, but meat was a relative rarity. The amount of land owned by the state and by great households varied over time, but the landscape always included some large, institutional estates that belonged to the king, nobles, and urban temples. The people built canals to carry water from the Tigris and Euphrates to the fields.

Industry and trade were well developed during periods when Babylonia was united under strong central rule. The Babylonians exported manufactured goods, mainly textiles, to many parts of the Middle East. Traders brought back metal, wood, and stone—materials lacking in Babylonia—from as far away as what are now India, Bahrain, and Oman. Mud brick, an unfired brick made of clay or mud, was the chief building material for most structures.

The ziggurats (temple towers) that stood in the important cities were the most impressive buildings. The Babylonians discovered many technical devices to erect buildings. They paid careful attention to drainage, used slightly curved lines in high walls to keep them from appearing top-heavy, and developed mathematical measuring techniques.

Language and literature.

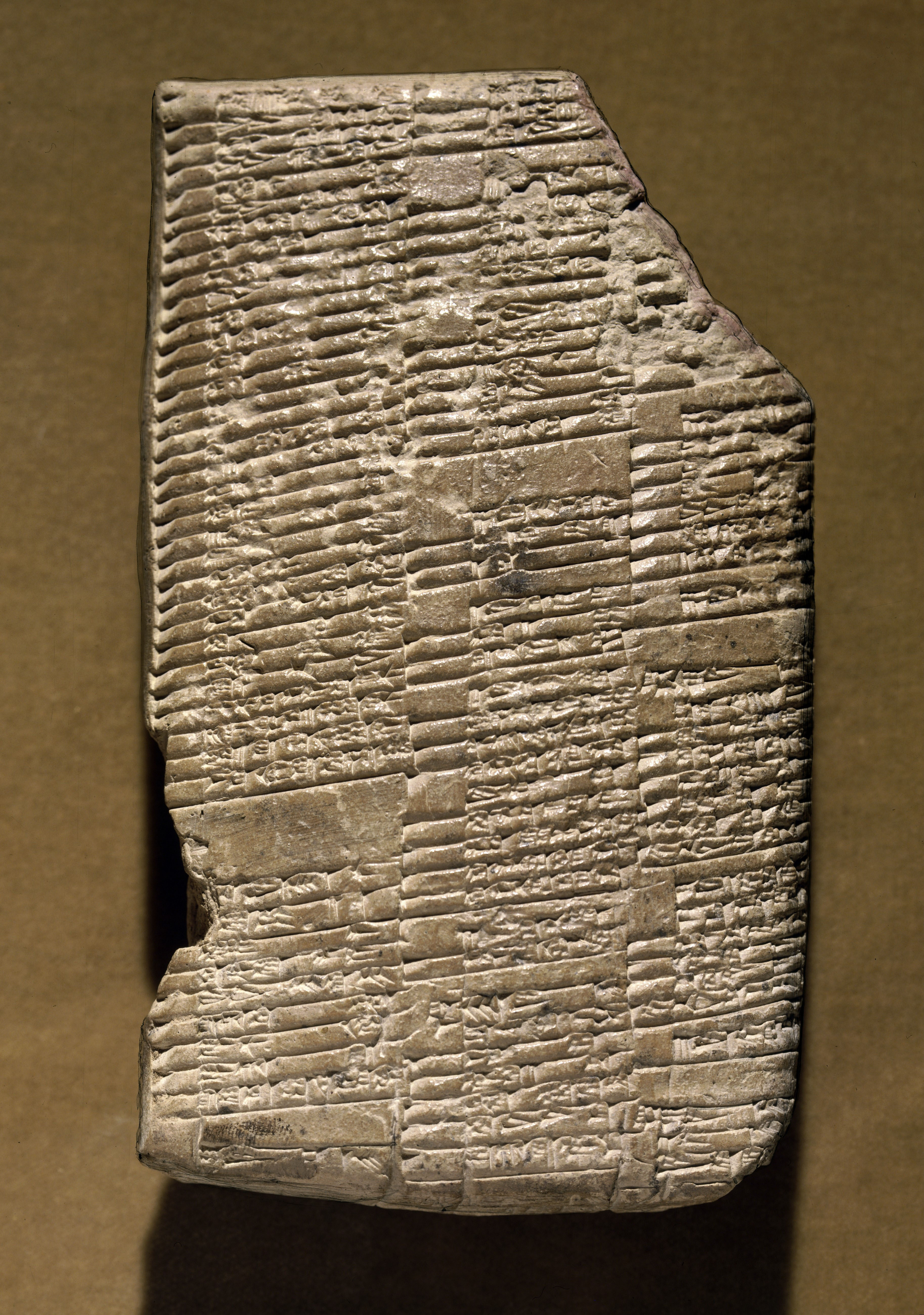

The Babylonians spoke different dialects of Akkadian, a Semitic language related to Hebrew and Aramaic. They adopted the cuneiform writing system of the Sumerians to express their own language. Archaeologists have discovered nearly half a million cuneiform tablets produced by the Babylonians.

Business documents make up the majority of the known texts. They record private and institutional business transactions as well as a sophisticated system of credit. There was no money. The Babylonians routinely valued goods by their weight in silver or grain.

Babylonian literature usually came from the upper classes. Royal literature included law codes, accounts of military campaigns and building projects, hymns praising royalty, and historical chronicles. Babylonian mythology combined old stories about Sumerian deities (gods and goddesses) with newer Babylonian stories. The most famous of these accounts are the Creation Story, which tells how the god Marduk created the world, and the Epic of Gilgamesh, the tale of a great hero who struggles with the problem of being mortal. The story of Gilgamesh includes an account of a flood that resembles the story of Noah’s ark in the Bible.

Religious and ritual texts are relatively few, but they provide clues about religious practices in the temples. More numerous are the thousands of literary-scientific texts, which combine scientific and ritual-magical modes of knowledge. The Babylonians believed that everything in the visible world held a particular meaning.

Mathematical and astronomical texts show that the Babylonians developed complex systems to compute algebraic and geometric functions. They understood such ideas as fractions, squares, and square roots. They could predict solar and lunar eclipses and the rising of planets and stars.

Religion.

The Babylonians adopted the major deities of ancient Sumer, sometimes giving them new names. Eventually, they worshiped thousands of major and minor gods. Various deities were associated with major cities, natural forces, heavenly bodies, and a variety of professional arts. It was important for kings to secure the support of individual city temples, whose resident gods were said to bless them and justify their rule.

A hierarchy of priests cared for deities believed to live in the temples. The priests clothed and bathed statues of the deities and gave them food.

Temple priests distributed barley to hundreds and thousands of people, making the temples centers of large economic communities. Some temples also housed writing centers that produced literature and scientific observations.

Art.

The finest Babylonian artwork—jewel-encrusted statues of deities—has not survived to the present day. Letters from several periods document other lost craftworks, such as exotic wood furniture, gold and silver decorative vessels, and jewelry. Business records indicate that Babylonian textiles were commercially important, but no examples of these textiles remain.

Babylonian pottery developed in several distinct styles over the centuries. The production of carved cylindrical seals, used to seal documents and storerooms, was another important craft. The Babylonians rolled the seals in wet clay to produce an imprint.

History

The first settlers in southern Babylonia probably arrived about 5000 B.C. They most likely came from communities of farmers and herders who had lived in the surrounding foothills since around 9000 B.C.

Sumerian city-states.

The Sumerians were among the earliest people of the area later called Babylonia. Small, independent city-states (cities and their surrounding territory) existed in the area as early as about 4000 B.C. By 3300 B.C., these included several large cities that shared common cultural elements, such as writing technologies and architecture. For the next several hundred years, Uruk, Ur, Kish, Umma, Lagash, and other cities waged local wars, each occasionally ruling neighboring areas. Sometimes, they acted together for purposes of trade and mutual defense. Lagash was perhaps the most aggressive in its local conquests. But it was overthrown along with the other Sumerian cities around 2350 B.C. by the new Semitic-speaking Akkadian dynasty.

The Akkadian and Neo-Sumerian periods.

The first in a series of Semitic-speaking dynasties took over Babylonia when Sargon of Akkad conquered the region in the 2300’s B.C. Later legends celebrated Sargon’s heroic feats of leading his army north to Anatolia and west to the Mediterranean Sea. The Akkadians controlled Babylonia for about 140 years, during which time the Sumerian cities carried out many revolts against them.

The Akkadian empire collapsed sometime after 2200 B.C. Historians later blamed its downfall on tribes of mountain people called Gutians. After about 60 years, a new Sumerian-style dynasty arose at the city of Ur. It controlled Sumer and lands to the east for a century.

The dynasties of Babylon.

Ur collapsed in 2004 B.C. A series of Babylonian dynasties and periods of disorder followed. The First Dynasty of Babylon flourished from about 1900 to 1600 B.C. It reached its height under King Hammurabi, who reigned from 1792 to 1750 B.C. The dynasty’s territory had already been reduced to a fraction of its size when a Hittite army conquered it in 1595 B.C. Sometime after 1595 B.C., a people called the Kassites took control of Babylonia. After the Kassites, several kings ruled Babylonia for short periods. During this time, the power of the monarchy was limited.

Babylon, the capital of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, threw off Assyrian domination in 626 B.C. By 539 B.C., Babylonia had taken over most Assyrian lands. King Nebuchadnezzar II, who reigned from 605 to 562 B.C., rebuilt Babylon on a grand scale. Babylonia was part of the Persian Empire from 539 B.C. until Alexander the Great took over the region in 331 B.C. Significant occupation of Babylon had ended by about 100 B.C.