Nationality, in law, is a person’s status as a member of a certain country. Usually, a person’s citizenship is the same as his or her nationality. But the terms do not mean exactly the same thing. For example, before the Philippine Islands became independent in 1946, their people were nationals of the United States. They owed allegiance to the United States but were not U.S. citizens.

Nationality is acquired at birth according to either of two principles. The first is the jus sanguinis, or right of blood, which gives to a child the nationality of one of the parents, usually the father. The second, called jus soli, or right of the place of one’s birth, makes a person a national of the country in which he or she is born. Most countries use both principles. Every country has the right to determine who its nationals shall be.

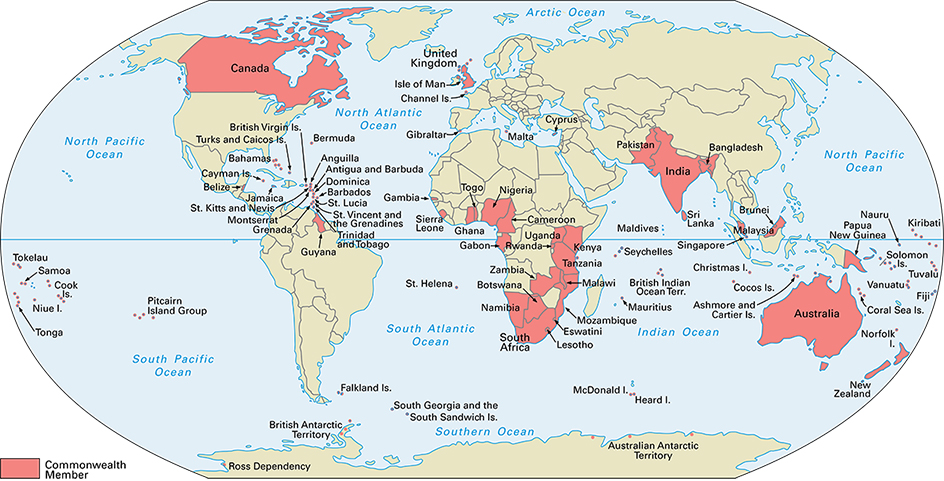

In the Commonwealth of Nations,

the difference between nationality and citizenship was once important. The Commonwealth is an association of mainly independent countries formerly under British rule. All people living in the Commonwealth were considered to be both British subjects and citizens of their own countries. Today, however, citizens of Commonwealth nations are not considered British subjects. A British subject also may be a citizen of a Commonwealth nation if he or she meets that nation’s citizenship requirements.

Nationality groups.

Nationality also refers to the fact that many people continue the habits, the customs, and even the language of their native land when they go to live elsewhere. Many groups of people in U.S. cities try to keep alive the customs and traditions of other countries. Some of these people were born outside the country. But in some cases, every member of the group was born in the United States.