New Deal was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s program to pull the United States out of the Great Depression in the 1930’s. The New Deal did not end the Depression. However, it relieved much economic hardship and gave Americans faith in the democratic system at a time when other nations hit by the Depression turned to dictators. Roosevelt first used the term new deal when he accepted the Democratic presidential nomination in 1932. “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people,” he said.

When Roosevelt became president on March 4, 1933, business was at a standstill, the banking system was near collapse, and a feeling of panic had gripped the nation. The stock market crash in October 1929 had shattered the prosperity most Americans enjoyed during the 1920’s. The Depression grew worse during the early 1930’s, as banks, small businesses, and factories closed. Workers lost their homes and farmers lost their farms because they could not meet mortgage payments. By 1933, an estimated 12 to 15 million Americans—1 out of 4 workers—had no jobs. The Depression struck minority groups especially hard. In the African American community, unemployment rates hovered near 50 percent.

In his inaugural address, Roosevelt expressed confidence that the nation could solve its problems. “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” he said.

The Hundred Days

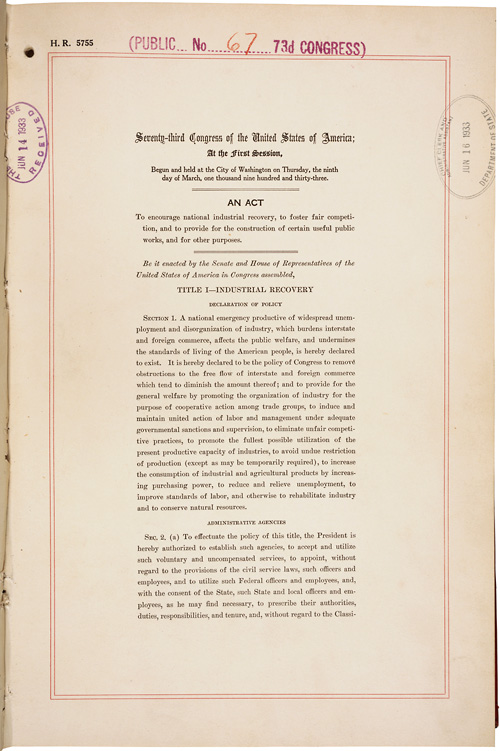

Roosevelt called Congress into special session on March 5, 1933. From March 9 to June 16, Congress passed a series of laws aimed at speeding economic recovery, providing relief for victims of the Depression, and reforming financial, business, agricultural, and industrial practices. Most laws passed swiftly and with little opposition. Never before had Congress approved so many important laws so quickly. The session became known as the Hundred Days. Many historians would later refer to this period as the First New Deal.

The programs and policies that made up the New Deal did not come from one person. Roosevelt, his presidential advisers (also known as the “Brain Trust”), and congressional leaders all proposed ideas. Some programs conflicted with each other. For example, the Economy Act cut the salaries of federal employees while the Public Works Administration increased government spending. But Roosevelt was willing to experiment and tried the ideas of one group and then another.

Helping savers and investors.

Roosevelt’s first goal was to end the banking crisis. A wave of bank failures in February had frightened the public. Depositors rushed to withdraw their money before their banks failed. Roosevelt declared a “bank holiday,” closing all banks on March 6. On March 9, Congress passed the Emergency Banking Act. The new law allowed government inspectors to check each bank’s records and to reopen only those banks that were in strong financial condition. Within a few days, half the nation’s banks reopened. These banks held 90 percent of the country’s total deposits. This action did much to end the nation’s panic.

The Glass-Steagall Banking Act of June 1933 provided further protection for investors. It gave the Federal Reserve Board more power to regulate loans made by banks and created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which first insured bank deposits up to $2,500 and later, in July 1934, up to $5,000.

Congress passed the Securities Act of 1933, also called the Truth-in-Securities Act, in May 1933. This law required firms issuing new stocks to give investors full and accurate financial information. Congress created the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 1934 to regulate the stock market.

Helping the farmers.

The Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), created in May 1933, was a centerpiece of the Hundred Days. It sought to raise farm prices by limiting production. The AAA gave farmers “benefit payments” if they agreed not to produce as much as they had before. The plan increased farm income, but critics argued that farmers should not cut food and cotton production at a time when people were hungry and needed clothing. In addition, tenants and sharecroppers, many of whom were African American, rarely received any portion of the benefit payment given to the landowner. In fact, the measure encouraged landowners to evict tenants and sharecroppers because landowners had fewer acres to cultivate.

In United States v. Butler (1936), the Supreme Court of the United States declared the AAA unconstitutional. The government then paid farmers to leave some land vacant as part of new soil conservation programs.

Helping industry and labor.

The National Industrial Recovery Act of June 1933 was another centerpiece of the Hundred Days. This act created the National Recovery Administration (NRA) to enforce codes of fair practices for business and industry. Representatives of firms within each industry wrote the codes, which allowed the firms to set quality standards and minimum prices. The codes primarily aided business.

The industrial codes set minimum wages and maximum hours, and supported the right of workers to join unions. However, some unions refused to admit African Americans. Many industries also refused to include black workers in the NRA protections and paid them less than whites. Some African Americans referred to the NRA as “Negro Run Around” or “Negroes Ruined Again.” The Supreme Court declared the National Industrial Recovery Act unconstitutional in 1935, and the NRA was abolished (see Schechter v. United States ).

Helping the needy.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) launched the New Deal relief program. The CCC put young men from needy families to work at useful conservation projects, such as planting trees and building dams. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration provided the states with money for the needy. The Public Works Administration (PWA) created jobs for large numbers of people. It built thousands of schools, courthouses, bridges, dams, and other projects. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) built dams to control floods and to provide electricity for residents of the Tennessee River Valley.

The Second Hundred Days

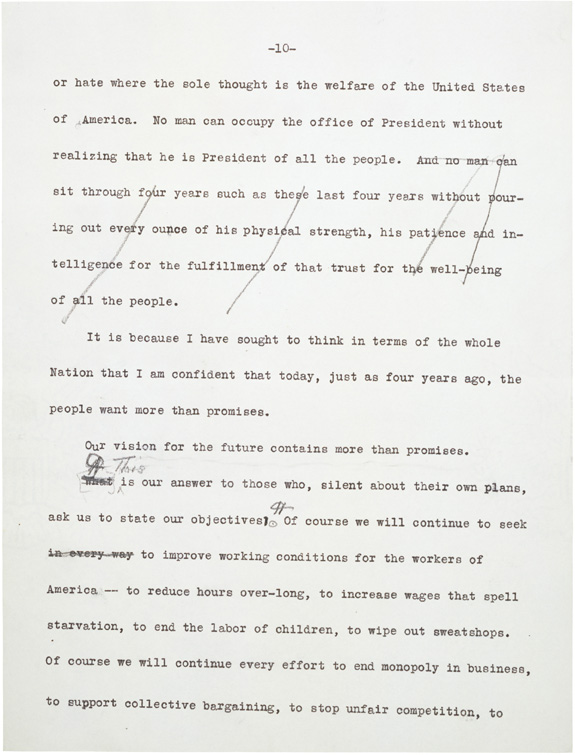

Congress approved several important relief and reform measures in 1935. These laws, which tended to emphasize economic security, became the heart of the lasting achievements of the New Deal. Most of these new laws were passed during the summer, and some historians call this period the Second Hundred Days, or the Second New Deal. The most important new measures included the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the National Labor Relations Act, and the Social Security Act.

Works Progress Administration

provided jobs building highways, streets, bridges, parks, and other projects intended to have long-range value. It also created work for artists, writers, and performers. The WPA provided some work for about 8 1/2 million people. It was renamed the Work Projects Administration in 1939.

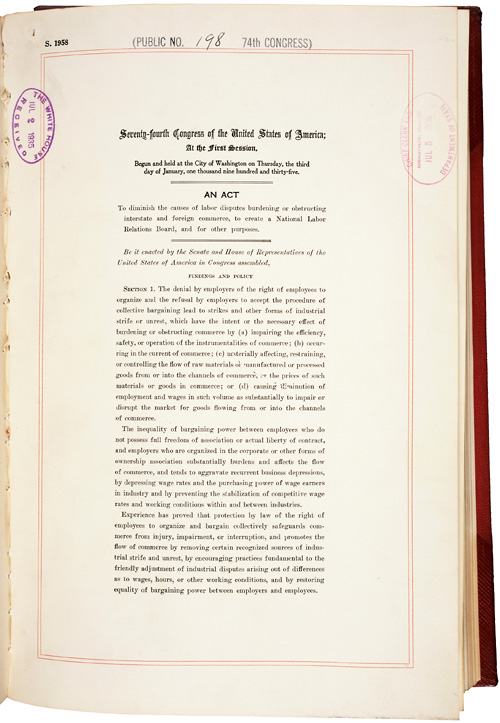

The National Labor Relations Act

guaranteed workers the right to organize unions. During the next few years, the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) enrolled millions of workers in labor unions.

The Social Security Act

provided pensions for the aged and insurance for the jobless. The law also provided payments for people with disabilities and for needy children (see Social security ). However, by exempting farm and domestic workers, the law excluded two-thirds of the African American labor force from benefits.

The final measures

In its final and least successful phase, the New Deal aimed to expand the government’s capacity to provide services to the people. Some historians call this period the Third New Deal.

In 1937, Roosevelt proposed a plan to add justices to the Supreme Court. Critics charged that he was trying to “pack” the court with judges who favored the New Deal. Roosevelt’s plan divided the Democrats and cost him his solid support in Congress (see Roosevelt, Franklin Delano (The Supreme Court) ). Congress passed only two other important reform measures after 1936. The first was the United States Housing Act of 1937, which provided money for more public housing projects. The second was the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938, which set a minimum wage of 25 cents an hour and a maximum workweek of 44 hours, with extra pay for extra hours. The act also banned child labor. However, the FLSA excluded farm and domestic workers.

The economy faltered late in 1937. Farm prices dropped, and the number of jobless people rose from about 5 million in September 1937 to almost 11 million in May 1938. The Democrats retained majorities in both houses of Congress in the 1938 elections, but Republicans gained back seats for the first time since 1928. Strong opposition in Congress forced Roosevelt to avoid further reforms, and he soon became occupied primarily with the growing threat of Nazi Germany.

Results of the New Deal

Most scholars agree that the New Deal relieved much economic distress and brought about a measure of recovery. But about 8 million Americans still had no jobs in 1940. Military spending for World War II (1939-1945), rather than the New Deal, brought back prosperity.

The New Deal caused major political changes. The Democratic Party, generally a minority party since the American Civil War (1861-1865), became the largest political party. Its main strength shifted from the rural South to the urban North. Minorities, immigrants, union members, urban intellectuals, and reformers became more prominent in the party.

Most scholars agree that the New Deal preserved the essentials of the U.S. free enterprise system. Profits and competition continued to play a leading part in the system. But the program added new features. The federal government became responsible for the economic security of the people and the economic growth of the nation. After the New Deal, the government’s role in public welfare and banking grew steadily, and organized labor became a key force in national affairs.