Bacteria are simple organisms that consist of one cell. They rank among the smallest living things. Most bacteria measure from 0.3 to 2.0 microns in diameter and can be seen only through a microscope. A micron equals 0.001 millimeter or 1/25,400 inch. Most scientists classify bacteria in the domain Bacteria, a group that also includes the algaelike cyanobacteria. All members of this domain have prokaryotic cells that lack a nucleus. Scientists call such organisms prokaryotes (see Prokaryote).

Bacteria exist almost everywhere. There are thousands of species (kinds) of bacteria, most of which are harmless to human beings. Large numbers of bacteria live in the human body but cause no harm. Some species cause diseases, but many others are helpful.

The importance of bacteria

Helpful bacteria.

Certain kinds of bacteria live in the intestines of human beings and other animals. These bacteria help in digestion and in destroying harmful organisms. Intestinal bacteria also produce some vitamins needed by the body.

Bacteria in soil and water play a vital role in recycling carbon, nitrogen, sulfur, and other chemical elements used by living things. Many bacteria help decompose (break down) dead organisms and animal wastes into simpler chemical compounds. Other bacteria help change chemical elements into forms that can be used by plants and animals. For example, certain kinds of bacteria convert nitrogen in the air and soil into nitrogen compounds used by plants (see Nitrogen cycle).

Various bacteria cause a chemical process called fermentation. People use fermentation to make alcoholic beverages and cheese and many other foods. Sewage treatment plants use bacteria to purify water. Bacteria also are used in making some drugs.

Bacterial cells resemble the cells of other living things in many ways, and so scientists study bacteria to learn about more complex organisms. For example, the study of bacteria has helped researchers understand how certain characteristics are inherited. Most types of bacteria reproduce quickly. This rapid reproduction enables scientists to grow large quantities for research.

Harmful bacteria.

Some bacteria cause diseases in human beings. These diseases include cholera, gonorrhea, leprosy (Hansen’s disease), pneumonia, syphilis, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and whooping cough. Air, food, and water can carry bacteria from one person to another. The bacteria enter a human body through its natural openings, such as the nose or mouth, or through breaks in the skin. In addition, air, food, and water carry bacteria from one person to another. Harmful bacteria prevent the body from functioning properly by destroying healthy cells.

Certain bacteria produce toxins (poisons) that cause such diseases as diphtheria, scarlet fever, and tetanus. Some toxins are produced by living bacteria, but others are released only after a bacterium dies. A form of food poisoning called botulism is caused by toxins from bacteria in improperly canned foods.

Bacteria that usually live harmlessly in the body may cause infections when a person’s resistance to disease is low. For example, if bacteria in the throat reproduce faster than the body can dispose of them, a person may get a sore throat.

Bacteria also cause diseases in other animals and in plants. Anthrax is a bacterial disease that infects many animals, especially cattle and sheep. Plant diseases caused by bacteria include fire blight, which occurs in apple and pear trees, and soft rot, which decays some fruits and vegetables. Bacteria also cause growths called crown galls, which attack various plants.

Protection against harmful bacteria.

Many bacteria live on the skin and in the mouth, intestines, and breathing passages. But the rest of the body tissues are normally free of bacteria. The skin, and the membranes that line the digestive and respiratory systems, prevent most harmful bacteria from entering the rest of the body. When harmful bacteria do enter the body, white blood cells surround and attack them. Also, the blood produces antibodies, substances that kill or weaken the invaders. Toxins are neutralized by certain antibodies called antitoxins. Sometimes the body cannot make its own antitoxins fast enough. In such cases, a physician may inject an antitoxin from an animal, such as a horse or rabbit, or from another person.

Dead or weakened bacteria are used in making drugs called vaccines, which can prevent the diseases caused by those bacteria. Vaccines are injected into the body, causing the blood to produce antibodies that attack the bacteria. Some vaccines protect the body from infection for several years or longer. Drugs called antibiotics are made by certain microorganisms that inhabit air, soil, and water. Antibiotics can kill or weaken other bacteria, including those that cause disease. But inappropriate use of antibiotics may favor the spread of bacteria resistant to the drugs. The drugs then become ineffective.

People use chemicals called antiseptics to prevent bacteria from growing on living tissues. Other chemicals, known as disinfectants, are used to destroy bacteria in water and on such items as clothing and utensils. Bacteria can also be killed by heat, and so heat is often used to sterilize food and utensils.

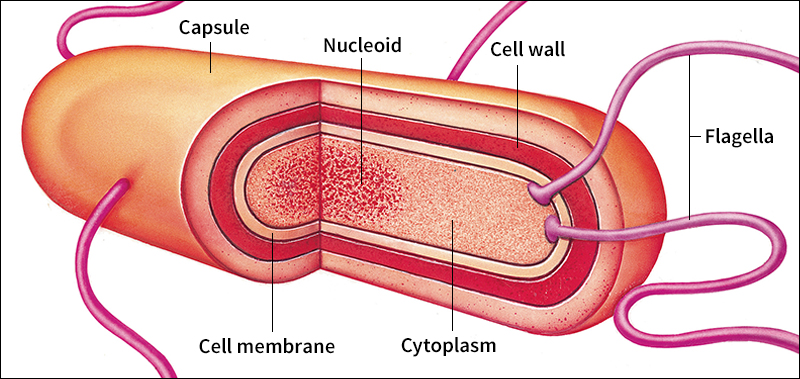

The structure of bacteria

Nearly all bacteria are enclosed by a tough protective layer called a cell wall. The cell wall gives the bacterium its shape and enables it to live in a wide range of habitats. Some species are further enclosed by a capsule, a slimy layer outside the cell wall. The capsule makes the cell resistant to destructive chemicals. All bacteria have a cell membrane, an elastic, baglike structure just inside the cell wall. The membrane prevents most harmful molecules from passing in and out of the cell. Inside the membrane is the cytoplasm, a soft, jellylike substance. The cytoplasm contains chemicals called enzymes, which help break down food and build cell parts.

Like the cells of all living things, bacterial cells contain DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid). DNA controls a cell’s growth, reproduction, and all other activities. The DNA of a bacterial cell forms an area of the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. Cells of animals, plants, and most other organisms contain a nucleus instead of a nucleoid. A nucleus is separated from the cytoplasm by a membrane.

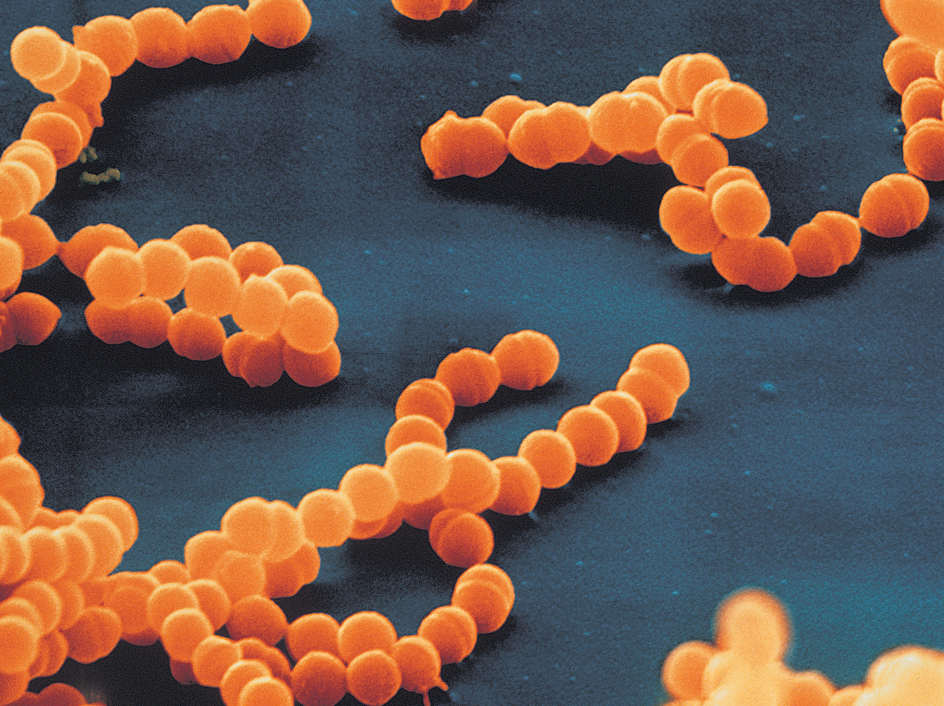

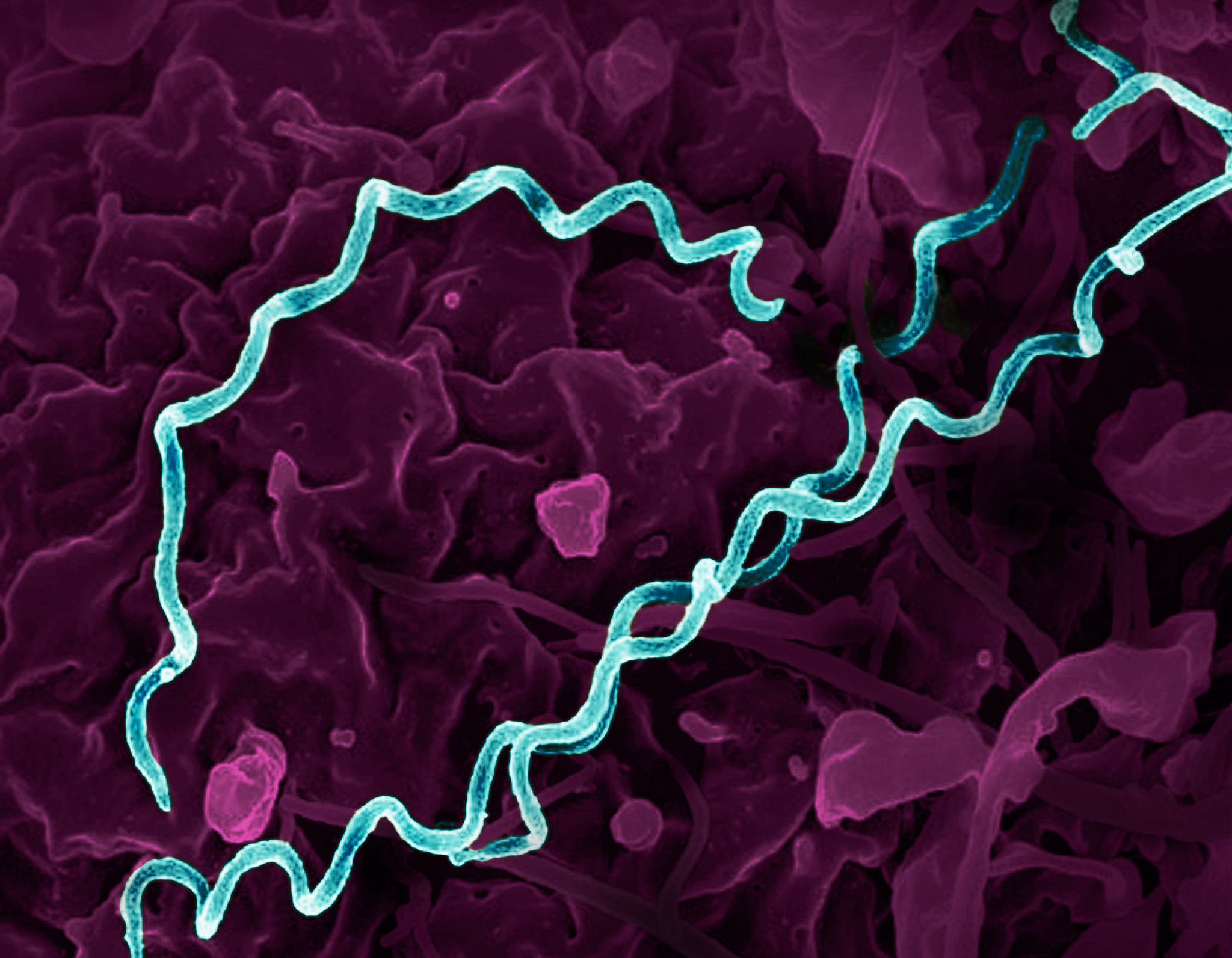

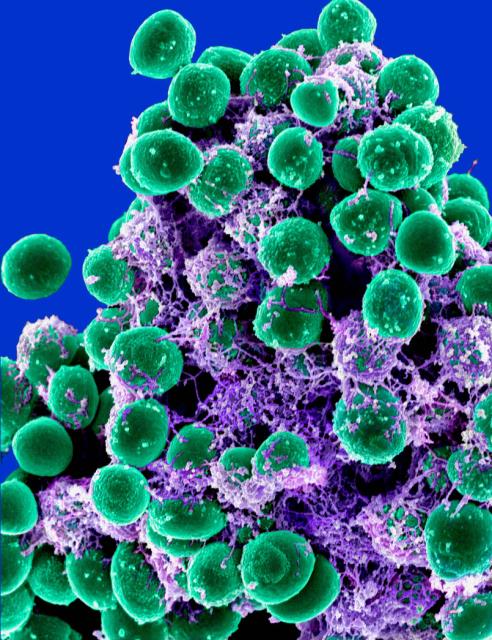

Scientists often name bacteria according to their shape. Round bacteria are called cocci, and rod-shaped ones are bacilli. Bacteria that look like bent rods are vibrios. There are two spiral-shaped bacteria, spirilla and spirochetes. Two or more bacteria linked together may be described by the prefixes diplo- (pair), staphylo- (cluster), or strepto- (chain). For example, streptococci are a type of round bacteria linked together in chains.

The life of bacteria

Where bacteria live.

Bacteria live almost everywhere, even in places where other forms of life cannot survive. The air, water, and upper layers of soil contain many bacteria. Bacteria are always present in the digestive and respiratory systems and on the skin of human beings and other animals. Such bacteria often occur in colonies of microorganisms called biofilms.

Certain bacteria, called aerobes, require oxygen to live, but others, known as anaerobes, can survive without it. Some anaerobes can exist either with or without oxygen. Other anaerobes cannot live with even a trace of oxygen in their environment.

Some bacteria protect themselves against a lack of food, oxygen, or water by forming a new, thicker cell membrane inside the old one. When the cell material surrounding the new membrane dies, the remaining organism, called a bacterial spore, becomes inactive. Bacterial spores may live for decades or even longer because they can resist extremely high or low temperatures and other harsh conditions. If food, oxygen, and water again become available, the spores change back into active bacteria.

How bacteria move.

Bacteria travel long distances on air and water currents. Clothing, utensils, and other objects also carry the organisms. Many bacteria have flagella (thin hairlike parts) that help them swim. Some species that lack flagella move by wriggling. Certain types have flagellalike parts called pili, which attach to other bacteria. In a process called twitching, they move by throwing out and attaching these pili to other bacteria and then pulling themselves toward the others.

How bacteria obtain food.

Some kinds of bacteria, called autotrophic bacteria, make their own food. For example, photosynthetic bacteria make food from carbon dioxide, sunlight, and water. Other types, known as heterotrophic bacteria, feed on molecules produced by other organisms. Some heterotrophic bacteria are parasites and may cause disease. But many others live in beneficial relationships with various organisms. Certain bacteria may be autotrophic or heterotrophic, depending on the food available.

How bacteria reproduce.

Most bacteria reproduce asexually—that is, each cell simply divides into two identical cells by a process called binary fission. Most bacteria also reproduce quickly, and some species double their number every 20 minutes. If one of these cells were given enough food, over a billion bacteria would be produced in 10 hours. Industrial and laboratory processes often produce such enormous numbers of bacteria. But in nature, bacteria lack an adequate food supply to maintain such a high rate of reproduction.

When bacteria reproduce by binary fission, the DNA in each of the two resulting cells is identical to the DNA in the original bacterium. Some bacteria can exchange DNA by a kind of simple sexual process called conjugation. Conjugation involves the direct transfer of DNA from one type of bacterial cell, called a male, to another type, called a female. DNA also may be transferred by viruses. In addition, bacteria may pick up fragments of DNA from dead bacterial cells. By transferring DNA, bacterial cells transfer individual traits. For example, bacterial cells that are resistant to certain antibiotics sometimes transfer this characteristic to nonresistant bacterial cells.

Scientists have developed techniques that enable them to isolate fragments of DNA responsible for particular traits. Inserting these fragments into different bacteria, called recombinant DNA technology, produces useful new kinds of bacteria. For example, some of these bacteria chemically break down oil and also help clean up oil spills. Others are used to make substances with medical applications, including insulin (see Insulin).

History

The first living things on Earth probably included bacteria. The oldest known fossils are those of bacteria that lived about 31/2 billion years ago. Some scientists believe certain bacteria gradually developed into the ancestors of the plants and animals of today.

Bacteria were first described in the mid-1670’s by Anton van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch amateur scientist. For many years, scientists believed that bacteria could spontaneously arise from nonliving matter in days or even hours. But in the late 1800’s, the French chemist Louis Pasteur showed that only living things can produce living things. Pasteur and Robert Koch, a German physician, helped develop the science of bacteriology (the study of bacteria). See Bacteriology.