Nuremberg << NOO ruhm `behrg` >> Trials were legal proceedings against Nazi Germany’s former leaders for crimes committed before and during World War II (1939-1945). The trials took place from 1945 to 1949 in Nuremberg, Germany, where Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party had once held its political rallies. The trials were the first successful war crimes trials conducted against senior national officials. The four countries that had defeated and then occupied Germany—France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States—organized the first trial.

The trials.

The defendants were charged with four kinds of crimes—conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Conspiracy is the act of planning crimes in advance. This legal concept allowed the prosecutors to try the Nazi government’s pre-war acts. Crimes against peace included launching a war in violation of international agreements. War crimes covered such acts as the mistreatment of prisoners of war, the plunder of occupied areas, and crimes on the high seas (areas of the oceans that lie outside the authority of any nation). Crimes against humanity involved the persecution and murder of people based on their political beliefs, race, or religions. A charter signed by the Allies before the trials established, for the first time, an international legal definition of crimes against humanity. This definition included acts committed before or during the war.

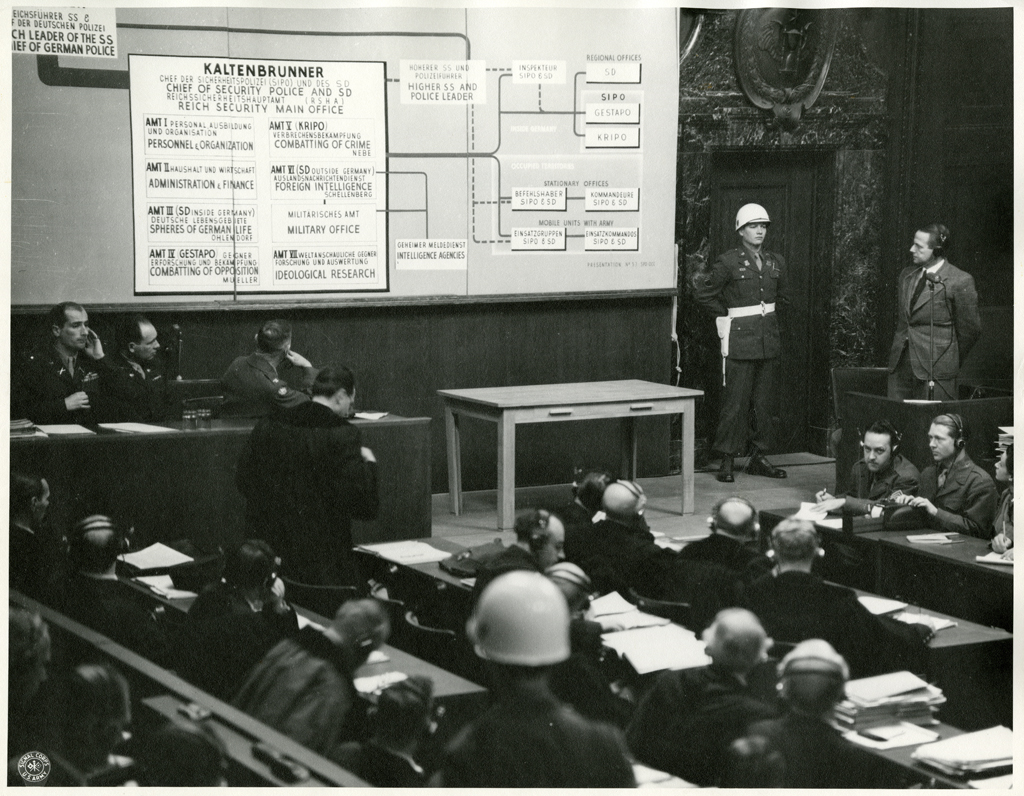

The first trial ran from November 1945 to October 1946. The International Military Tribunal, made up of British, French, Soviet, and U.S. judges and prosecutors, conducted the trial. The tribunal tried 22 high-ranking German leaders, including top Nazis Hermann Göring and Rudolf Hess; military leaders such as Wilhelm Keitel and Karl Dönitz; foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop; minister of armaments Albert Speer; and Ernst Kaltenbrunner, second in command of the elite Nazi Party guard known as the SS (Schutzstaffel). Twelve defendants received death sentences, seven received prison sentences, and three were found not guilty.

Individual countries conducted later trials of Nazi officials. At Nuremberg, U.S military tribunals held 12 trials from 1946 to 1949. Each trial examined a different set of crimes. For example, one trial focused on Nazi doctors who conducted experiments on concentration camp prisoners. Another involved the leaders of SS forces that had committed mass killings of Jews. Of the 185 defendants involved in the U.S. trials, 24 received death sentences, 107 received prison sentences, 35 were found not guilty, and 19 were released on other grounds.

Reaction.

The Nuremberg Trials triggered some criticism. The sentences were harsh, and no procedure existed for appealing the judgments. In addition, the Soviets, who participated in the International Military Tribunal, had engaged in war crimes themselves. Such charges as crimes against peace and humanity were new. As a result, some critics argued that the German defendants had violated moral rules but had not committed legal violations. Despite these criticisms, the Nuremberg Trials had far-reaching effects. They carefully documented Nazi actions, from launching World War II to murdering millions of European Jews. They also set the legal example, later adopted by the United Nations, that leaders can stand trial for crimes committed against their own citizens.