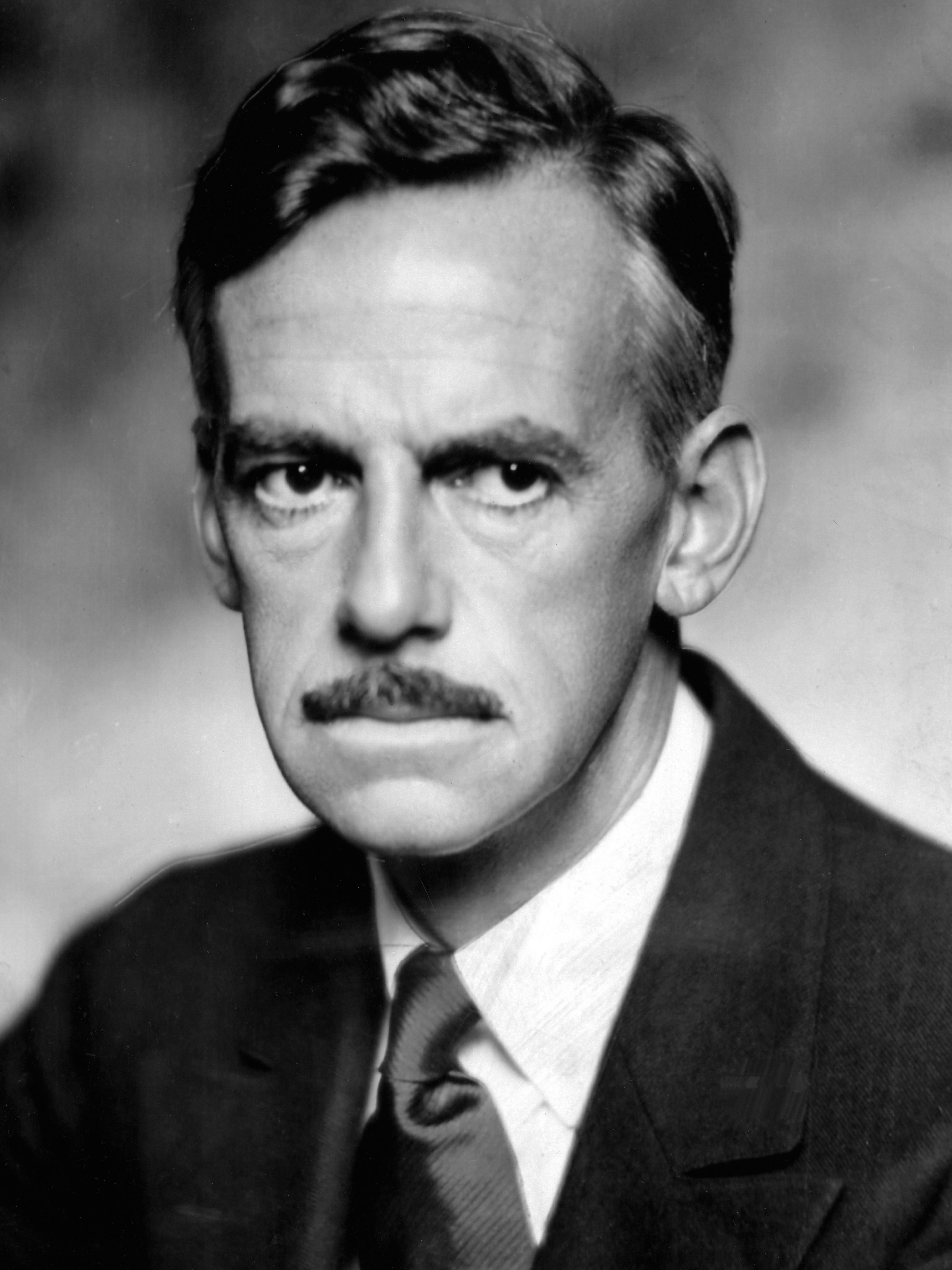

O’Neill, Eugene (1888-1953), is regarded as America’s greatest playwright. In 1936, O’Neill received the Nobel Prize in literature. Four of his plays won Pulitzer Prizes—Beyond the Horizon in 1920; Anna Christie in 1922; Strange Interlude in 1928; and Long Day’s Journey into Night in 1957, after his death.

O’Neill’s plays show his fascination with philosophy and religion and his intense self-examination. By incorporating experimental techniques of European theater into his plays, O’Neill is credited with raising the previously narrow and insubstantial American drama into an art form that gained worldwide respect.

His life.

Eugene Gladstone O’Neill was born in New York City on Oct. 16, 1888. His father, James O’Neill, was one of America’s most popular actors. Between national tours, the family spent the summers in New London, Connecticut. Their home provided the setting for two of O’Neill’s greatest plays—Ah, Wilderness! (1933) and Long Day’s Journey into Night (written from 1939 to 1941 and first performed in 1956). In New London, O’Neill discovered his mother’s addiction to morphine and rebelled against his father’s theatrical conservatism. O’Neill was raised a Roman Catholic, but he rejected religion. He married in 1909 but was divorced within three years. By 1912, O’Neill had worked as a gold prospector in Honduras and a seaman and had become a frequenter of cheap saloons and flophouses in New York City. That year, he returned to New London and became ill with tuberculosis.

O’Neill’s reading while recovering at a sanitarium inspired him to become a playwright. In 1914, he studied drama with George Pierce Baker at Harvard University. In 1916, O’Neill joined the Provincetown Players, an experimental theater group on Cape Cod in Massachusetts. In July, the group presented Bound East for Cardiff, the first staging of an O’Neill play.

O’Neill’s second marriage, to writer Agnes Boulton, in 1918 ended in divorce in 1929. Later that year, he married actress Carlotta Monterey. He wrote until the mid-1940’s, when a muscular disease resembling Parkinson disease prevented further work. O’Neill died on Nov. 27, 1953, largely forgotten. But in 1956, a revival of The Iceman Cometh (written in 1939) and the premiere of Long Day’s Journey into Night aroused a renewed interest in his plays.

His plays.

O’Neill’s career consisted of two periods of Realism divided by a middle period of experimentation. He first wrote one-act plays that utilized his youthful experiences, especially at sea. The best of these plays include four Realistic works that trace the changing relationships among seamen of the S.S. Glencairn amid the tensions of World War I (1914-1918).

In the early 1920’s, O’Neill rejected Realism and determined to capture on stage the “force behind” human life. He was influenced by the ideas of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, the Austrian psychologist Sigmund Freud, the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung, and the Swedish playwright August Strindberg.

In The Emperor Jones (1920), an Expressionistic play, O’Neill traced the personal and racial past of a Black porter who becomes a Caribbean dictator. The Hairy Ape (1922) blends Realistic and Expressionistic elements in the story of an alienated man’s attempts to belong in modern society. Desire Under the Elms (1924) transplants the Greek myth of Phaedra and Hippolytus and elements of other myths to a New England farm.

In The Great God Brown (1926), the characters wear masks that express or hide their inner natures. In the nine-act Strange Interlude (1928), characters voice inner thoughts that frequently contradict their public utterances. Mourning Becomes Electra (1931) is a trilogy that shifts the Greek tragic trilogy the Oresteia to America immediately after the Civil War (1861-1865). The gods and Furies of Greek mythology are replaced by the workings of the subconscious mind.

O’Neill’s final period was his best as he returned to Realism and the more open acknowledgment of a lifelong impulse to write autobiographical plays. The Iceman Cometh immortalizes the unrealistic “pipe dreams” of the friends from the flophouses and Greenwich Village. The play’s characters shield themselves from the bitter truth of failure through their mutually supportive illusions. A Touch of the Poet, written from 1935 to 1942 and first staged in 1957, is the only complete drama of a planned 11-play cycle. O’Neill intended the cycle to trace the life of an Irish American family and the spiritual decline of America from the early 1800’s. In his greatest play, Long Day’s Journey into Night, the Tyrone family is clearly based on O’Neill’s own family in 1912. A Moon for the Misbegotten (written from 1941 to 1943 and first performed in 1957) is a sequel that portrays the last days of O’Neill’s alcoholic brother, Jamie. In 1988, the Library of America published an authoritative three-volume edition of O’Neill’s Complete Plays (1913-1943).

See also Long Day’s Journey into Night.