Opera is a drama in which the characters sing, rather than speak, all or most of their lines. Opera is one of the more complex of all art forms. It combines acting, singing, orchestral music, costumes, scenery, and often ballet or some other form of dance.

In telling a story, opera uses the enormous power of music to communicate feeling and to express emotions. Singers, accompanied by an orchestra, may bring a dramatic situation to life more vividly than actors with spoken dialogue. Vocal and orchestral music can also tell an audience much about a character and his or her state of mind.

Because music expresses emotions so forcefully, most opera composers base their works on highly emotional stories. An opera, more than a spoken play, is likely to emphasize passionate scenes of anger, cruelty, jealousy, joy, love, revenge, sadness, or triumph. Music can also add excitement to scenes portraying spectacle. Some of the most stirring music in opera accompanies colorful crowd scenes, such as a coronation or a military parade.

Opera differs in several ways from other kinds of plays that have music. For example, William Shakespeare’s comedy A Midsummer Night’s Dream has scenes that call for music. Such music is called incidental music because the play is dramatically complete without it. Different productions of the same play may use incidental music by different composers.

Musical comedies and operettas resemble opera, but most of them have much more dialogue than an opera has, and their music is lighter. Compositions called oratorios also share certain features with opera. Like an opera, an oratorio has music for soloists, chorus, and orchestra. It may also tell a story. But unlike operas, almost all oratorios are performed in a concert hall and without acting, costumes, or scenery.

Organizations called opera companies produce most operas. Most companies are repertory theaters—that is, they present several operas alternately during a season. The operas a company presents are called its repertoire.

Operas are usually performed in specially designed theaters called opera houses. Most opera houses seat many more people than do theaters reserved for spoken drama. An opera house also has special facilities and equipment to provide the elaborate staging required by many operas. All modern opera houses have an orchestra pit between the stage and the seats of the auditorium. From the pit, the orchestra, led by the conductor, accompanies the singers onstage.

Most opera houses built in the 1700’s and 1800’s, and some modern ones, have rows of boxes arranged in the auditorium. Originally, the boxes were owned by the nobility who patronized the opera and were occupied by their families and guests. Because it is difficult to get a good view of the stage from many box seats, modern opera houses rarely feature this arrangement.

Opera, as we know it today, began in Italy in the late 1500’s. Through the years, Italian composers, singers, and conductors have played a leading role in the development of opera. By the end of the 1600’s, opera had spread from Italy to other European countries. Today, opera can be enjoyed in many parts of the world.

The best-known companies in Europe include those that perform at the Teatro alla Scala (La Scala) in Milan, Italy; the Opera House in Rome; the Opera de la Bastille and the Opera-Comique in Paris; the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in London; the State Opera in Vienna; and the Festival Opera House in Bayreuth, Germany.

The most famous opera company in the United States is the Metropolitan Opera Association, which performs in New York City. The Boston Opera Company, the Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco Opera Company are also famous. Other important American companies include the Greater Miami Opera, the Houston Grand Opera, the Seattle Opera, and the Washington (D.C.) Opera. Every summer, the Santa Fe Opera Company performs in an outdoor theater in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

The elements of opera

An opera has two basic elements: (1) the libretto and (2) the music. The libretto, which means little book in Italian, consists of the words, or text, of an opera. The music, which is also called the score, consists of both vocal and instrumental music. To translate the libretto and music into a performance, an opera must have singers, a conductor, and an orchestra.

The libretto

To enjoy an opera fully, an operagoer should read the libretto or a summary of the action beforehand. It is especially important to read a translation of the libretto or a summary if an opera is sung in an unfamiliar language. Some public libraries have librettos. Most of them have books that contain summaries of the action in individual operas. Generally, an opera house provides a program that has a summary of the plot. Most American opera houses provide translations on a screen above the stage.

The libretto of most operas is shorter than the text of a spoken play because it takes longer to sing a given number of words than to speak them and because some words and phrases may be repeated for emphasis. Librettos may also be shorter than the script of a spoken play because a few measures of music can often express emotions more vividly than many lines of spoken dialogue can. Because a libretto has to be relatively short, the story of an opera is likely to be simpler than that of a spoken play, with fewer characters and fewer secondary plots.

Many operas have been criticized for their poor librettos. Such operas give the impression that the composer used the text merely as an excuse for the music. Many people do attend the opera mainly to hear beautiful music sung by beautiful voices. Other people, however, feel that a good opera must also be a good drama. And in fact, some librettos are excellent works of literature. These librettos include those that the Austrian poet Hugo von Hofmannsthal wrote for the operas of Richard Strauss and adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays that composer-poet Arrigo Boito made for two operas by Giuseppe Verdi..

The definition of good drama in opera has changed over the years. Numerous subjects that were popular in operas of the 1600’s, 1700’s, or 1800’s are now out of fashion. Yet modern operagoers can still enjoy these older operas if they learn something about the customs in drama and music that influenced their composition.

Recitative and arias.

Certain parts of the libretto simply provide information for the audience. For example, one character may tell another about something that has happened. In some operas, the characters speak these portions of the text. But in many operas, including nearly all Italian operas, the characters sing them in a simple, speechlike style called recitative. Most recitatives are written in everyday language—that is, they do not rhyme. Recitatives were especially popular in operas of the 1700’s and early 1800’s.

The most emotional parts of the libretto are solo numbers called arias. They usually express a character’s feelings or thoughts. Most arias are written in rhythmical, rhymed verse. They are also set to far more elaborate music than are recitatives. In fact, arias provide the most beautiful and dramatic music in many operas.

Spoken dialogue or recitative carries the action forward. At intervals, the action stops and the characters sing arias to express their feelings. An example of the use of recitative and aria appears in the following passage from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni. In the passage, a character sings several lines of recitative, ending with:

Every means must be sought to discover the truth … I shall avenge her!

He then sings an aria that begins with these lines:

My peace depends on hers; that which pleases her gives life to me. …

The recitative above tells the audience about the character’s future actions. The aria expresses his state of mind. The original Italian text for this aria was written in rhymed poetry.

Ensembles.

In many operas, the libretto calls for two or more singers to engage in a musical dialogue, called an ensemble. The most common ensembles are duets, trios, quartets, and quintets. Some ensembles require several characters to sing at the same time and express their thoughts and feelings. They may sing the same words, showing agreement. Or they may sing different words and melodies, expressing conflicting feelings and thoughts.

The music

The singers.

In an opera, each role calls for a singer with a specific voice range. Opera singers are therefore classified according to the range of their voices.

The basic vocal classifications for women, from highest to lowest range, are soprano, mezzo-soprano, and contralto. Each of these classifications can be divided into more specialized groups. For example, sopranos can be divided into coloratura sopranos, lyric sopranos, and dramatic sopranos. Coloratura sopranos have a very high range and can sing with great agility. Lyric sopranos have a light, graceful voice appropriate to youthful roles. Dramatic sopranos have a rich, strong voice suited to highly emotional parts.

The chief voice classifications for men, from highest to lowest range, are tenor, baritone, and bass. Each classification can be divided into more specialized groups. For example, tenors can be divided into lyric tenors and dramatic, or heroic, tenors. A lyric tenor has a light, high voice. A dramatic tenor, often called by the German word Heldentenor, has a rich, powerful voice with a lower range than a lyric tenor. Such voices are needed for the heroic roles in operas by Richard Wagner. Bass voices are classified as basso cantante, basso buffo, or basso profundo. A basso cantante has the highest bass voice, with a character similar to that of a lyric tenor. A basso buffo has a deeper, flexible voice and sings comic roles. A basso profundo has an especially low voice and usually sings majestic, serious roles.

Choral singing.

Most operas include choral singing as well as arias, recitatives, and ensembles. The function and importance of the chorus vary from opera to opera and even within an opera. A chorus may provide only visual background for a scene. For example, it might portray a crowd at a festival. Or a chorus may be required merely to shout an exclamation, such as “Hail to our great king!” But in some works, the chorus plays a leading part in the story and sings complicated music.

Acting in opera.

For a successful career in opera, a singer must have acting skill in addition to an outstanding voice. Most young singers who plan a career in opera take several years of acting lessons.

Opera acting presents special problems because it is difficult to act and sing at the same time. Sudden movements, walking, running, and twisted body positions may all interfere with the production of a beautiful, clear, and steady tone. For this reason, opera acting tends to be less lively and less realistic than acting in other forms of drama.

The conductor

plays a key role in opera. Throughout a performance, the conductor must keep the singers and orchestra together. The beat must be clearly seen by singers far from the conductor and by musicians sitting in the dim light at the ends of the orchestra pit. Although the conductor sets the tempo, he or she must be able to react to unexpected circumstances. If a soloist begins to sing faster, for example, the conductor may have to adjust the orchestra’s tempo. Because of all these special demands, opera conducting requires greater skills than does any other kind of conducting.

Some operas call for scenes in which musicians and singers perform offstage. In such instances, an assistant conductor directs the offstage music. In some modern opera houses, the assistant conductor directs the off-stage music while following the conductor’s beat over closed-circuit television.

The orchestra.

The number and kinds of instruments in the orchestra depend on the opera being performed. The instruments needed for Italian operas composed in the late 1700’s differ greatly from those needed for operas written by Wagner in the late 1800’s.

The particular opera being performed also determines the orchestra’s function. In most operas, the orchestra’s basic job is to accompany the singers. The accompaniment may be simple, providing only enough harmonic and rhythmic background to keep the singers on pitch and in time. But the orchestra may also serve a more important role. For example, it might play music that introduces the general emotional quality of an aria before a note has been sung. The orchestra may even emphasize a passage in the text. For example, a heavily rhythmic beat might accompany the words “my heart pounds faster.”

In some scenes, one or more characters may be alone a long time without singing or speaking. During that period, the orchestral music expresses their feelings. This kind of characterization through music is one of the strengths of opera and is impossible in spoken plays.

In many operas, the orchestra often repeats a melody or short theme from an earlier scene. This melody or theme, without singing or spoken words, is called a leitmotif. Composers repeat the leitmotif to remind listeners of some action, character, or idea previously introduced in the opera. Composers of the 1800’s, notably Wagner, used the leitmotif most effectively.

Pieces of orchestral music called interludes are sometimes used to connect scenes. Interludes provide time for scenery changes or for new characters to enter. Interludes also may indicate shifts in the emotional atmosphere in an opera. Occasionally, orchestral music imitates the sounds of nature. In Wagner’s Siegfried, the orchestra imitates the sounds in a forest.

Most operas begin with an orchestral overture. Some overtures merely indicate that the performance is about to begin. But others have a more important function. Some introduce the opera’s principal melodies. Others set the mood for the opening scene or for the opera in general. In some older operas, the overture is uncomplicated and brief. A number of overtures of the 1800’s are elaborate pieces that run 10 minutes or longer.

Musicians occasionally perform onstage in costume and participate in the action of the opera. For example, musicians may take part in such onstage activities as a military parade or a religious procession.

Producing an opera

An opera company produces several operas in a season. In selecting each work for production, the company must consider several factors. These factors include the estimated cost of presenting the opera and whether the work will attract a large audience. Most opera companies attempt to balance their season with both comic and tragic operas. They also try to select works by a variety of composers and from different historical periods.

The people behind the scenes

During an opera performance, the audience sees only the conductor, orchestra, and performers. But an opera production also requires the skills of many other people. These people include (1) the general manager, (2) the stage director, (3) costume and set designers, (4) the members of the technical staff, and (5) the stage manager. All these specialists perform about the same work for an opera as they would for a spoken play. But opera requires that they coordinate all parts of the production with the music.

The general manager

supervises the overall artistic and business policy of the opera company. This person plays a major part in choosing the repertoire and in hiring singers, conductors, and stage managers. The general manager follows each production through the planning and rehearsal stages to make sure it is progressing satisfactorily. Some companies have a music director or artistic director who controls the hiring of singers and conductors.

The stage director

is responsible for the visual aspects of an opera production, just as the conductor is responsible for the music. The stage director must coordinate every action on the stage with the music. The director helps singers interpret their roles, works with the designers on ideas for costumes and sets, and helps determine the lighting. See Theater (The director).

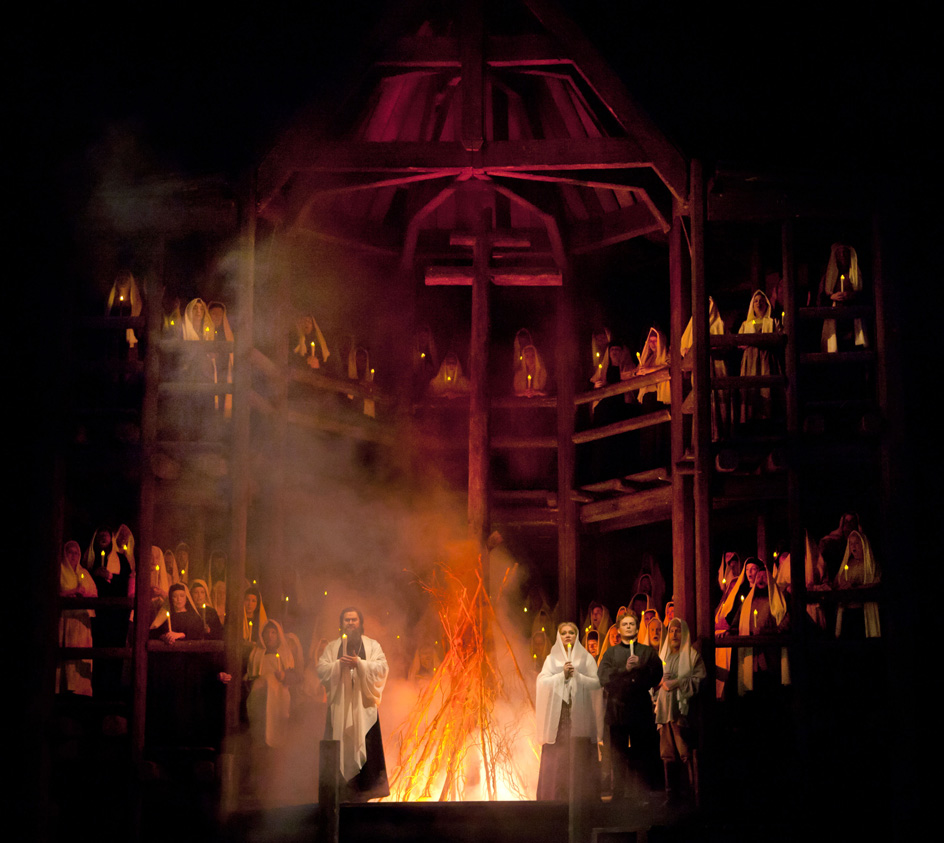

The stage director faces one of the greatest challenges in handling choral scenes. The chorus should not simply stand still and look at the conductor while singing. All dramatic illusion would be lost. The director must assign all members of the chorus some activity so they will appear natural on the stage. Some operas have scenes in which the chorus takes part in vigorous action while singing. One such scene takes place near the end of Act II of Wagner’s opera The Mastersingers of Nuremberg. A riot breaks out among a crowd of angry townspeople played by the chorus. In such scenes, the chorus must act convincingly while singing and following the conductor. The stage director has to plan choral scenes like these carefully and then rehearse the scenes frequently.

Sometimes, a stage director may create a new interpretation of an opera. Because the repertoire of opera companies consists chiefly of a few dozen works performed repeatedly, audiences may welcome a production that presents a familiar opera in a fresh way. But some directors have been criticized for taking too many liberties with an opera, for example, by setting it in a different historical period.

The designers.

The story of most operas in the standard repertoire takes place before the 1900’s. Therefore, the costume and set designers must generally research the particular period of the story so their designs accurately reflect the time and place of the action. In Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida, for example, the costumes and sets should realistically portray ancient Egypt.

The costumes and sets should be designed so that the performers can move about freely. In addition, the set designer always has to consider the requirements of the music. For example, the music may allow a singer a certain amount of time to move from a door to a table and begin an aria. The designer must arrange the set so the singer can move naturally and still arrive at the table at the precise moment in the music when the aria begins. The set designer may also have to plan the sets to provide space for large choral or dance scenes. See Theater (Scene design) (Costumes and makeup).

The technical staff.

Many technicians work with the stage director in planning and carrying out the visual aspects of the production. The electricians are especially important members of the technical staff. They operate the complicated lighting equipment that is used to illuminate parts or all of the stage and to provide atmosphere. Some stage directors rely on lighting, rather than on realistic sets, to express an opera’s mood. See Theater (Lighting and sound).

During an opera performance, the various crews of technicians and stagehands must work quickly, quietly, and efficiently backstage. One crew changes the scenery between acts or scenes. Another crew adds the small objects, called props, that the performers use in the action. A third crew sets up and adjusts the lights. For changing scenery, some opera houses use revolving stages or stages that can be raised or lowered by elevator. Special technicians operate the machinery that moves these stages. See Theater (Changing scenery).

The stage manager

has charge of all backstage activity during a performance. He or she sees that all the props needed for a scene are on the stage and in the correct place. The stage manager calls the performers from their dressing rooms at specific times so they can make their entrances on schedule. The stage manager also gives the electricians cues to change the lighting during the performance.

Preparing a production

Planning a production.

After a company selects an opera, the general manager and the management staff establish the production’s budget. They also choose the cast and assign a stage director and conductor to the production. Most companies employ a resident group of singers, conductors, and directors for an entire season. However, nearly all companies also hire guest singers to take the leading roles for a single production. In addition, companies frequently use guest conductors, stage directors, and designers.

In some cases, the most important consideration in selecting an opera is whether a company can hire a particular guest singer. Sometimes a company wants a certain singer so much it will let the artist choose the opera. In casting the leading parts, the opera company first of all seeks singers who have outstanding voices. But the performers should also act well and, preferably, have the physical appearance suited to the characters they are to portray.

During the early stages of a production, the key personnel hold many conferences. The stage director, for example, meets frequently with the costume and set designers. Sketches of the designs must be approved early to allow enough time for the costumes and sets to be made. The costumes and sets may be manufactured in the opera house workshops or by outside firms. Sometimes, sets and costumes are borrowed or rented from another opera company.

Rehearsing a production.

After many months of planning the production, rehearsals begin. At first, the singers, chorus, and orchestra rehearse separately in rehearsal rooms. If the opera calls for dancing, the dancers also practice by themselves.

The stage director rehearses the principal singers to work out stage movements and establish interpretations of the roles. The chorus rehearses under the direction of a chorus master. A choreographer (dance creator) supervises dance rehearsals. The conductor and the conductor’s assistants rehearse the orchestra.

A few weeks before the opera is to open, rehearsals move from separate facilities to the main stage. These rehearsals take place with piano accompaniment only.

Meanwhile, the stage director and the chief electrician hold lighting rehearsals. In most operas, directors use elaborate lighting that is changed frequently during the performance. Lighting rehearsals develop the best ways to achieve desired effects. The rehearsals also set the timing for the various lighting changes.

As the opening nears, the orchestra rehearses with the entire cast on the main stage. Because of the central function of the music, the conductor takes charge of these rehearsals.

A few days before opening night, the performers and orchestra stage a dress rehearsal. A dress rehearsal is presented like an actual performance, with costumes, makeup, and sets. By this time, the production should move with split-second timing. The music sets the pace for the action and should not have to be sped up or slowed down to adjust to what happens onstage.

The development of opera

The first operas were composed and performed in the 1590’s in Florence, Italy. There, a group of noblemen, musicians, and poets had become interested in the culture of ancient Greece, especially Greek drama. This group, called the Camerata, believed that the Greeks sang rather than spoke their tragedies. The Camerata attempted to re-create the spirit of ancient Greek tragedy in music. They took most of their subjects from Greek and Roman history and mythology. The Camerata called their compositions dramma per musica (drama for music) or opera in musica (musical work). The term opera comes from the shortened form of opera in musica. Jacopo Peri, a member of the Camerata, composed what is generally considered to be the first opera, La Dafne (1597).

Baroque opera

Opera emerged as an art form in western Europe during the Baroque period in music history. This period began about 1600 and ended about 1750. Baroque music was elaborate and emotional. Italians composed the earliest Baroque operas, and Italian-style opera dominated most of the period.

Early Baroque opera.

The first Baroque operas consisted of recitatives, sung by soloists, and choral passages. A small orchestra accompanied the singers.

During the 1600’s, the aria gradually emerged and developed as a separate function from that of the recitative. The recitative served to carry the plot of the opera forward. The arias became pauses in the action in which characters expressed their thoughts and feelings. Singers often used arias for showing off their vocal skills rather than for dramatic expression. A very common form of presentation called simple recitative developed in the 1600’s. In it, the singers were accompanied by only a harpsichord—or by a harpsichord and cello or other bass instrument—rather than by the full orchestra.

Claudio Monteverdi, the first great composer of Baroque opera, wrote the first opera masterpiece, Orfeo (1607). Later, Monteverdi worked in Venice and helped make the city the center of opera by the mid-1600’s. The world’s first public opera house, the Teatro San Cassiano, opened in Venice in 1637.

By the late 1600’s, operas were being written and performed in a number of European countries outside Italy, especially in England, France, and Germany. Italian opera was the accepted style, and many non-Italian composers wrote operas in the Italian manner and to Italian librettos.

Opera seria and opera buffa.

Italian opera of the early 1700’s developed into two basic types—(1) opera seria (serious opera) and (2) opera buffa (comic opera). Both types consisted of a succession of recitatives and arias.

Opera seria.

Composers of opera seria based their works on stories of ancient heroes and heroines. In the 1600’s, similar stories had included both comic and serious characters. They had provided spectacular stage effects, such as earthquakes and floods and big coronation or battle scenes. But comic scenes and spectacle were eliminated from serious opera in the 1700’s. Emphasis fell instead on the skills of the principal singers. By the 1800’s, many singers were trained in a vocal style called bel canto, which emphasized technical skill and beauty of tone. The da capo aria became a major feature of opera seria. It had three parts, the third being a repetition of the first. In the repeated part, the singer was expected to add difficult passages and other ornamentation not included in the score.

Opera buffa

began as comic skits, called intermezzi, performed in front of the curtain between the acts of an opera seria. The characters in opera buffa were common people, unlike the characters in opera seria. Characters in opera buffa represented the professions and social classes of the time, including doctors, farmers, merchants, servants, and soldiers. The typical opera buffa dealt with humorous situations from everyday life. Many characters in opera buffa sang in dialects (local forms) of Italian rather than the formal Italian of opera seria. A very successful intermezzo was La serva padrona (1733) by Giovanni Pergolesi.

Italian opera seria and opera buffa were extremely popular. Hundreds of them were written, often in a short time. Most of these works were performed for one season and then forgotten. Because of the constant demand for new operas, composers used the same librettos over and over again. By today’s standards, many librettos have unconvincing plots and unbelievable characters. Although some operagoers complained about the weak librettos of many Italian operas, most audiences of the 1600’s and early 1700’s enjoyed the works, chiefly for their music.

French opera.

A distinctly French style of opera appeared in the 1670’s. Before that time, the French showed little interest in opera. The few operas performed in the country were written in the Italian style. Jean-Baptiste Lully, though born in Italy, established a French form of opera. In the mid-1700’s, Jean-Philippe Rameau became the leading composer of French opera.

French opera composers avoided the rapid recitatives and showy arias of Italian opera. Instead they preferred expressive melodies or simple songs. The recitatives were accompanied by a full orchestra and closely followed the rhythms of the French language. Ballet played an important part in French opera during the Baroque period, as well as later.

In France, royalty became the chief patrons of opera. Lully acquired his fame at the court of King Louis XIV. The nobility in France and other countries competed with one another in maintaining large opera companies. To impress audiences with their wealth, the nobility sponsored productions noted for expensive scenic effects, such as gods riding chariots in the sky.

Classical opera

Dissatisfaction with Italian opera began to spread among operagoers during the mid-1700’s. Attacks centered on the increasingly long and dramatically weak arias, which served only to glorify the singers. The reaction against Italian opera led to a series of reforms early in the Classical period. The Classical period began about 1750 and lasted about 70 years. The first important Classical opera composer was Christoph Willibald Gluck, a German. The greatest Classical composer was Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, an Austrian.

Loading the player...Opera: Classical

Gluck and opera reform.

Gluck believed drama and music should be unified in opera. By integrating the music with the story in Orpheus and Eurydice (1762) and other works, he put his beliefs into practice.

Gluck rejected improbable plots and emphasis on showy arias. In his operas, the music served the story. Gluck simplified the action to make the stories and characters appear more natural. He also was one of the first composers to supervise all aspects of a production.

Mozart,

like Gluck, felt that the music in an opera should help make the story and characters believable. Mozart achieved this goal by carefully relating the instrumental and vocal music to the action. He showed particular skill in using music to create characterization—that is, to develop the personality of a character. Mozart did this in ensemble scenes and in arias.

Mozart composed operas in both Italian and German. His best-known Italian operas are The Marriage of Figaro (1786), Don Giovanni (1787), and Cosi Fan Tutte (1790). His notable German operas include The Abduction from the Seraglio (1782) and The Magic Flute (1791). Both of these works contain elements of Singspiel (sung play). Singspiel is a form of German opera that has spoken dialogue rather than recitative. Most stories are comic. The melodies often are simple and resemble the style of German folk and popular songs.

Opera in the 1800’s

Romanticism

was a movement from the late 1700’s to the mid-1800’s that emphasized emotionalism in the arts, including opera. The typical Romantic opera had a setting in nature, a theme based on folklore or the supernatural, and colorful music. Carl Maria von Weber, a German, wrote one of the earliest and greatest Romantic operas, Der Freischutz (1821). The story is set in Germany’s Black Forest, and most of the chief characters are simple countrypeople. The orchestra has an important part in portraying many of the sounds of nature as well as supernatural forces.

Loading the player...Opera: Romanticism

Several Italians also created a Romantic style of opera. The most successful of these composers were Vincenzo Bellini and Gaetano Donizetti. Many of their operas require voices trained in the bel canto style.

Grand opera

became popular in the early 1800’s, especially in France. Composers of grand opera favored heroic episodes from history, in which they could use crowd scenes, spectacular stage effects, and complicated and elaborate vocal and instrumental music. Giacomo Meyerbeer, a German, became the leading composer of French grand opera with such works as Les Huguenots (1836) and Le Prophete (1849). Gioachino Rossini, an Italian-born composer living in France, also wrote a famous grand opera, William Tell (1829).

Loading the player...Opera: Grand opera

Giuseppe Verdi

dominated Italian opera during the mid- and late 1800’s. He is still perhaps the most popular opera composer in history. Verdi’s best-known works include Rigoletto (1851), Il Trovatore (1853), La Traviata (1853), and Aida (1871). All are noted for their emotional power, which is expressed through eloquent vocal music. Aida is also an example of grand opera.

Opera: Verdi

Verdi wrote his last two operas—Otello (1887) and Falstaff (1893)—when he was in his 70’s. Both works demonstrate that old age did not diminish but rather refined his genius. The operas are masterpieces of characterization through music, and they show complete fluidity of vocal and instrumental writing.

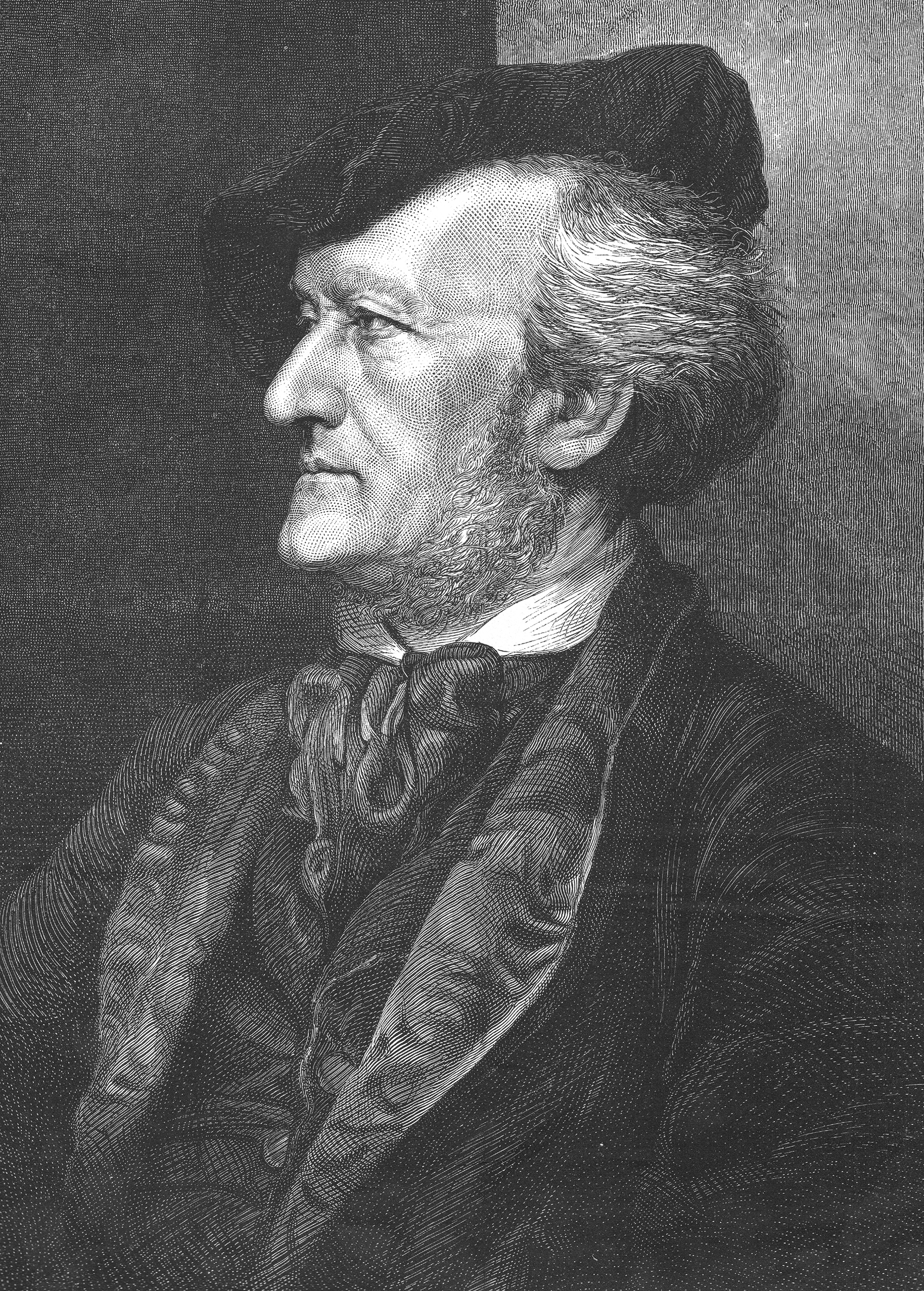

Richard Wagner

was the most important German opera composer of the 1800’s. Wagner believed that all the parts of an opera production—acting, costumes, drama, orchestral music, singing, and staging—should have equal value. He wrote his own librettos and, whenever possible, supervised the staging of a production. Wagner departed from tradition by making the orchestra as important as the singers. In many of Wagner’s late works, instruments perform the main melodies.

As a young man, Wagner was greatly impressed by Weber’s Romantic opera Der Freischutz. The Flying Dutchman (1843), one of Wagner’s early works, shows similar Romantic qualities. These qualities include the supernatural aspects of the plot and the musical representation of the forces of nature, such as the wind and the sea. In The Flying Dutchman, Wagner first used musical themes to identify certain characters, places, or ideas each time they appear in the drama. Wagner expanded this leitmotif technique greatly in his later operas. Tristan and Isolde (1865) and the four works called The Ring of the Nibelung (1876) represent Wagner’s fully developed personal style.

Nationalism

influenced many composers throughout Europe during the 1800’s. These composers based much of their work on the folk music of their nation or region. Czech nationalism, for example, dominates the operas of Antonín Dvorák and Bedrich Smetana. The Bartered Bride (1866) by Smetana and Rusalka (1901) by Dvorák are outstanding examples of nationalistic operas. Russian composers of nationalistic operas include Modest Mussorgsky with Boris Godunov (1874) and Alexander Borodin with Prince Igor (1890).

Loading the player...Opera: Nationalism

Verismo opera.

In the late 1800’s, some Italian composers began to write grimly realistic operas. These Verismo (meaning true or realistic) operas focused on violent emotions and actions. The earliest and best-known Verismo operas are Cavalleria Rusticana (1890) by Pietro Mascagni and Pagliacci (1892) by Ruggero Leoncavallo, both one-act works usually performed together.

Loading the player...Opera: Verismo

The 1900’s

Giacomo Puccini

was the most popular Italian opera composer of the early 1900’s. His operas are noted for their melodic and sometimes sentimental music and for their theatrically effective librettos. Puccini first gained widespread attention in the 1890’s with Manon Lescaut (1893) and La Boheme (1896). He followed these works with Tosca (1900), a Verismo opera. His other notable operas include Madama Butterfly (1904) and Turandot (produced in 1926, after his death).

Richard Strauss

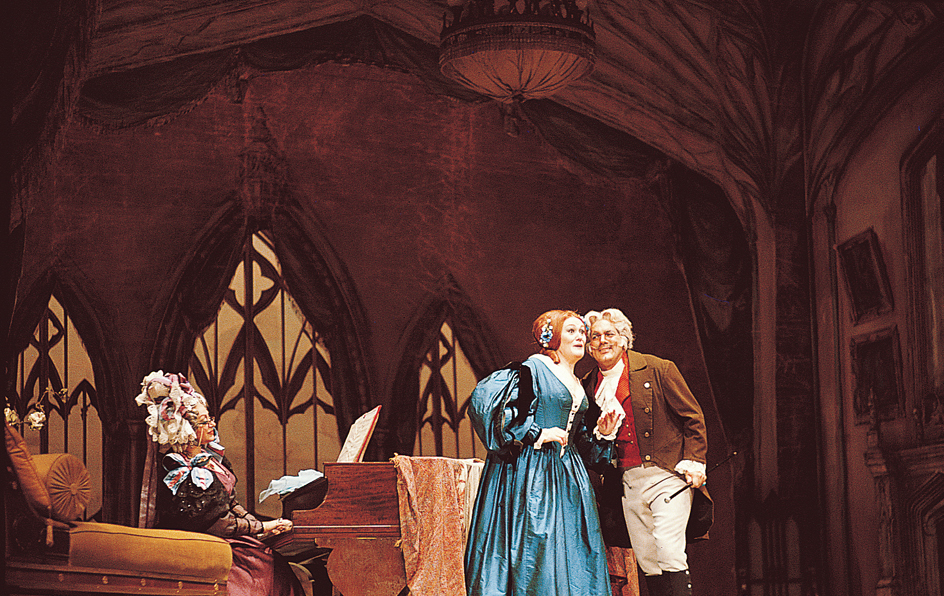

became the most important and successful German opera composer after Wagner. Strauss wrote operas that require singers with great vocal power. He is best known for three early operas—Salome (1905), Elektra (1909), and Der Rosenkavalier (1911). Salome and Elektra originally caused much controversy among operagoers because of their brutal action and harsh music. Der Rosenkavalier, however, is entirely different in mood and theme. In this opera, Strauss and the librettist, Hugo von Hofmannsthal, created an affectionate portrait of aristocratic society in Vienna in the 1700’s.

The search for new forms.

After World War I (1914-1918), many composers began to search for new forms of operatic expression. Some composers included elements of American jazz in their operas. Ernst Krenek, an Austrian, used jazz in his opera Jonny spielt auf (1927). The German composer Kurt Weill wrote The Threepenny Opera (1928) in the style of the music heard in German cabarets (nightclubs).

Meanwhile, a movement called Expressionism had developed in the arts. Expressionism aimed at exploring the subconscious and became especially important in drama and painting. But Expressionist qualities also appeared in several operas. Such operas had a brooding, nightmarish atmosphere, reinforced by dissonant music and symbolic and violent actions.

Strauss’s Salome was an early example of the Expressionist style. But Alban Berg, an Austrian composer, ranks as the leading opera composer in the movement. Berg wrote Wozzeck (1925), the most successful Expressionistic opera. Other operas related to Expressionism include Duke Bluebeard’s Castle (completed 1911, first performed 1918) by the Hungarian composer Béla Bartók and From the House of the Dead (1930) by the Czech composer Leoš Janáček.

Some of the most successful and theatrically effective operas of the 1900’s were written by the British composer Benjamin Britten. His opera Peter Grimes (1945) is a brooding but lyrical portrait of social alienation.

American opera.

American composers wrote no important operas until the 1900’s. George Gershwin wrote a highly original and popular American opera, Porgy and Bess (1935). The work describes life among blacks in Charleston, South Carolina, in the 1920’s. Porgy and Bess has been acclaimed worldwide as a genuine American folk opera.

The most successful opera composer in the United States is Gian Carlo Menotti. He composed in a traditional style that shows the influence of Puccini. Menotti wrote an opera for radio, The Old Maid and the Thief (1939), and an opera for television, Amahl and the Night Visitors (1951). His best-known stage operas include two tense dramas, The Medium (1946) and The Consul (1950).

Since World War II (1939-1945), the best operas have been written by more tradition-minded composers. They include Douglas Moore’s folk-inspired The Ballad of Baby Doe (1956) and Virgil Thomson’s The Mother of Us All (1947). The text for The Mother of Us All was written by American author Gertrude Stein.

Opera has played only a minor role in modern American experimental music. Some Americans associated with the Minimalist movement have written several important operas. The Minimalist style uses repeated short patterns of music with complex rhythmic variations but simple harmonies. Operas in this style include Philip Glass’s Einstein on the Beach (1975), which draws on rock music, and John Adams’s Nixon in China (1987).

Opera today

The experimentation in opera that began after World War I continues today. Some composers have explored new dramatic and musical techniques, including the use of electronic sounds, motion pictures, and color slides. Aniara (1959), a science-fiction opera by the Swedish composer Karl-Birger Blomdahl, takes place in a space ship and uses taped and electronic sounds. Bomarzo (1967) by the Argentine composer Alberto Ginastera also features unconventional sound effects, especially in fantastic, dreamlike scenes.

Operagoers today, however, still prefer older, traditional works. Only a few operas composed since the end of World War I receive frequent productions. But many changes have occurred in the way older operas are staged. For example, stage directors often try to create desired moods through lighting effects made possible by modern lighting equipment.

Meanwhile, artistic and economic problems trouble all major opera companies. Before the development of fast, convenient air travel, leading singers remained with one company an entire season. But jet travel enables singers to appear as guest artists in many opera houses in a season. Artists earn more money as guests, and audiences can see and hear many famous singers. However, traveling artists often follow a tight, exhausting schedule that leaves too little time for rehearsal. As a result, audiences often attend performances that show a lack of adequate preparation.

The cost of producing opera has risen steadily. Even if an opera house sells every ticket for an entire season, it cannot meet expenses. In the United States and Europe, ticket sales seldom provide more than half the income needed to operate an opera company. American companies rely on contributions from individuals, corporations, and foundations to make up losses. Many European countries, cities, and states support opera with public funds. Numerous people in the United States believe the national government or local governments should help support opera and the other arts, as governments do in Europe.

Most U.S. colleges and universities have opera workshops. They provide training and experience for young singers and also present performances for the general public. Some colleges and universities have staged revivals of worthwhile but little-known works.

The opera repertoire

Opera companies today present mainly works that were composed between the late 1700’s and the early 1900’s. Almost all the operas in this standard repertoire were written by Austrian, French, German, Italian, and Russian composers. This section describes some of the most popular operas in the standard repertoire. Some of the recommended books that are listed at the end of this article provide more detailed discussions of the repertoire.

Aida,

a tragic opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi. Libretto in Italian by Verdi and Antonio Ghislanzoni. First performed in Cairo, Egypt, in 1871.

The khedive (ruler) of Egypt asked Verdi to write Aida to help celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal and the Cairo opera house. The story takes place in ancient Egypt and concerns the tragic love affair between Aida, an Ethiopian slave, and Radames, an Egyptian military officer. Aida is grand opera and so requires a large cast. The work has impressive crowd scenes, featuring choruses of soldiers, slaves, and priests, and an elaborate ballet. In Act I, Radames expresses his love for Aida in a beautiful aria, “Celeste Aida.” Act II includes the stirring “Triumphal March,” in which the Egyptian king reviews his victorious army.

Aida: Triumphal March

Barber of Seville, The

(Il Barbiere di Siviglia), a comic opera in two acts by Gioachino Rossini. Libretto in Italian by Cesare Sterbini, based on the French play The Barber of Seville by Pierre de Beaumarchais. First performed in Rome in 1816.

The story of The Barber of Seville takes place in Seville, Spain, in the 1600’s. This work is a good example of Italian comic opera, or opera buffa. The libretto has many characters and situations typical of this style. The characters include an old man called Doctor Bartolo who is interested in a beautiful and rich young woman named Rosina. He jealously watches over her but cannot prevent a dashing young nobleman (Count Almaviva) from meeting and finally marrying her. Other traditional characters include a drunken soldier, who is really the count in disguise, and an irritable housekeeper. Figaro, the barber in the opera’s title, helps the count win Rosina.

In Act I, Rosina’s aria “Una voce poco fa” provides opportunities for brilliant singing. Also in Act I, Figaro makes his first appearance singing a popular comic aria, “Largo al factotum,” in which he boasts how clever he is. The opera also has a lively overture, which Rossini had used in two earlier operas.

Loading the player...The Barber of Seville: Una voce poco fa

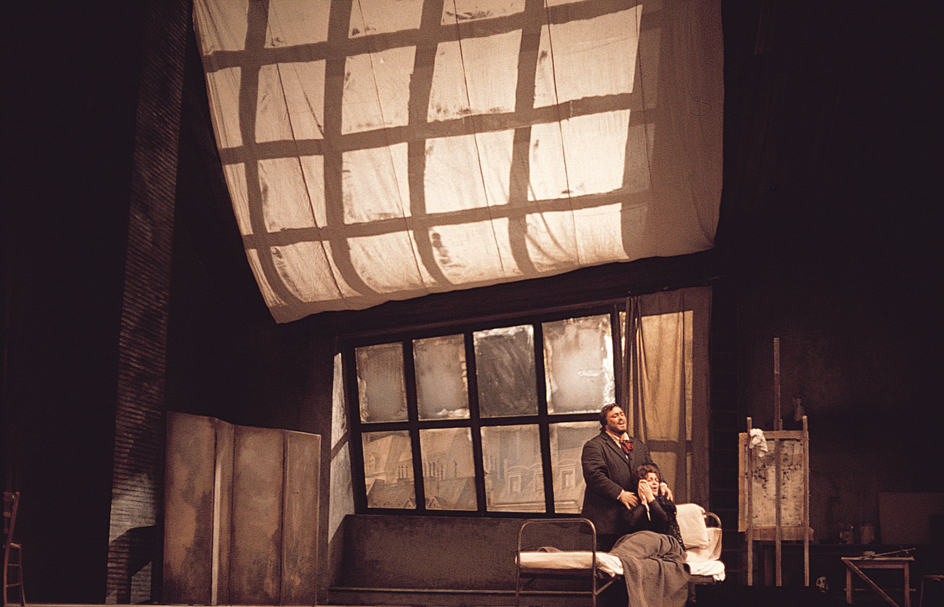

Boheme, La

(The Bohemian), a tragic opera in four acts by Giacomo Puccini. Libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on the French novel Scenes from Bohemian Life by Henri Murger. First performed in Turin, Italy, in 1896.

Four poor but carefree young men are living a bohemian life together in an attic in Paris about 1830. They are Rodolfo, a poet; Marcello, a painter; Schaunard, a musician; and Colline, a philosopher. Mimi, a frail young girl in poor health, is their neighbor. She and Rodolfo meet and fall in love. But at the end of the opera, Mimi dies. The main secondary plot deals with a stormy love affair between Marcello and a young woman named Musetta.

Although La Boheme ends tragically, it has many humorous and sentimental moments. The opera also has a number of Puccini’s most beloved melodies. One of these melodies is “O soave fanciulla,” a love duet between Rodolfo and Mimi that ends Act I. Perhaps the opera’s most familiar melody is the aria “Musetta’s Waltz” in Act II.

Loading the player...La Bohème

Boris Godunov,

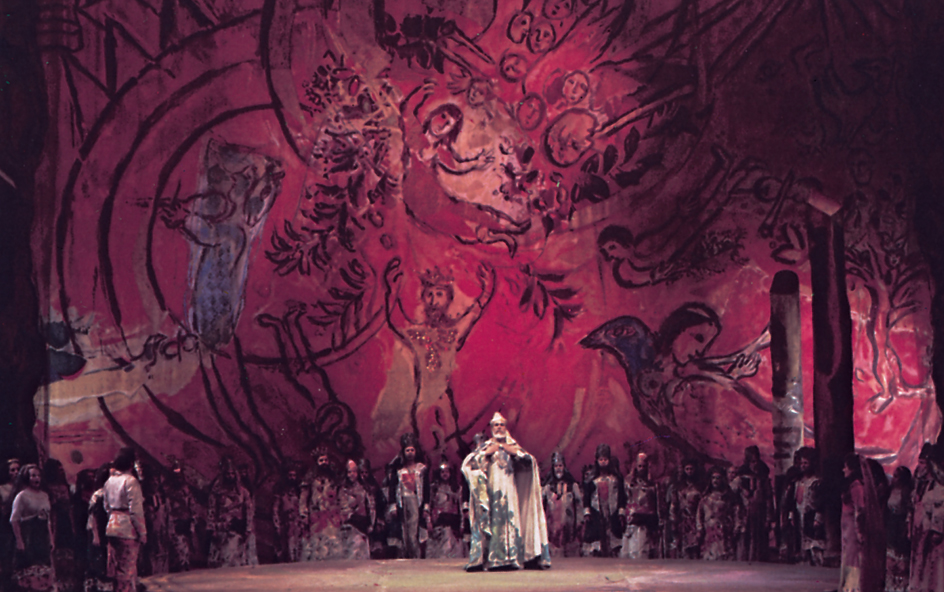

a tragic opera in a prologue and four acts by Modest Mussorgsky. Libretto in Russian by the composer, based primarily on the Russian play Boris Godunov by Alexander Pushkin. First performed in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1874.

The opera takes place in Russia and Poland from 1598 to 1605 and concerns Russian historical figures. Boris Godunov, an adviser to the czar, has the czar’s young heir murdered. After the czar dies, Boris takes the throne. But in time, his feelings of guilt cause him to have visions of the murdered heir, and he finally collapses and dies. The “hero” of the opera is the Russian people, portrayed by the chorus. The chorus takes part in many scenes, including an impressive coronation.

Many musicians in Mussorgsky’s time considered the music for Boris Godunov too harsh and crude. After Mussorgsky’s death, his friend and fellow Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov revised the orchestration for the opera. Rimsky-Korsakov’s version is often performed today.

Carmen,

a tragic opera in four acts by Georges Bizet. Libretto in French by Ludovic Halevy and Henri Meilhac, based on the French story “Carmen” by Prosper Merimee. First performed in Paris in 1875.

The action of Carmen is set in and near Seville, Spain, about 1820. Carmen is a beautiful Gypsy dedicated to a life of unrestrained freedom. While working in a cigarette factory in Seville, she meets Don Jose, a soldier, and has a love affair with him. Later, she leaves Don Jose for Escamillo, a bullfighter. At the end of the opera, Don Jose pleads with Carmen to return to him. After she scornfully refuses, Don Jose stabs her to death in a jealous rage.

Loading the player...Carmen

The exciting plot, colorful Spanish setting, and stirring music have made Carmen one of the most popular works in the repertoire. Many of the opera’s melodies have become almost as familiar as popular songs. They include Carmen’s dancelike arias “Habanera” and “Seguidilla” in Act I and Don Jose’s “Flower Song” and Escamillo’s “Toreador Song” in Act II. The opera also has rousing choral and dance numbers.

Cavalleria Rusticana

(Rustic Chivalry), a tragic opera in one act by Pietro Mascagni. Libretto in Italian by Guido Menasci and Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti, based on the Italian story and play Cavalleria Rusticana by Giovanni Verga. First performed in Rome in 1890.

Traditionally, Cavalleria Rusticana is performed with Ruggero Leoncavallo’s two-act opera, Pagliacci. The passion, realism, and violence of both works make them major examples of Verismo opera.

The action in Cavalleria Rusticana takes place in a Sicilian village in the 1800’s. There, Lola, a married woman, has a love affair with Turiddu, a young soldier. The title of the opera refers to the villagers’ code of honor. According to this code, Alfio, Lola’s husband, must seek revenge. He challenges Turiddu to a duel and kills him.

The composer and librettists used several effective dramatic devices. Halfway through the opera, the villagers are in church, and the stage is empty. During this interval, the orchestra plays the “Intermezzo.” This gentle, melodic instrumental piece provides relief from the tense, highly emotional atmosphere of the opera. In another dramatic device, Turiddu’s death takes place offstage. The opera audience learns of the outcome of the duel through the horrified reactions of the villagers onstage.

Don Giovanni,

a comic opera with serious elements in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Libretto in Italian by Lorenzo da Ponte. First performed in Prague, Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), in 1787.

Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni has become the best-known version of the legend about Don Juan, the Spanish rogue. The action takes place in and near Seville, Spain, in the 1600’s. In the opening scene, Don Giovanni (Don Juan) flees from the home of Donna Anna after trying to seduce her, and then he kills her father in a duel. Several later episodes further show Giovanni’s immoral nature. At the end of the opera, the marble statue of Donna Anna’s slain father visits Giovanni and urges him to abandon his sinful ways. Giovanni refuses. The scene is then enveloped in smoke and fire as he disappears into hell, dragged off by a chorus of demons.

Loading the player...Don Giovanni

The mixture of comic and serious qualities of Don Giovanni has always fascinated audiences. Leporello, Giovanni’s servant, provides most of the comedy. The most serious figure is Donna Anna. In addition to many beautiful arias, Don Giovanni has highly dramatic recitatives and long, complicated ensembles. In one scene in Act I, three orchestras onstage perform three different dance numbers at the same time during a party given by Don Giovanni. While the three onstage orchestras play, the opera orchestra in the pit accompanies the singers.

Faust,

a tragic opera in five acts by Charles Gounod. Libretto in French by Jules Barbier and Michel Carre, based on part I of the German play Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. First performed in Paris in 1859.

The story of Faust takes place in Germany in the 1500’s. Faust is an old philosopher who yearns for his lost youth. Mephistopheles, the Devil, appears to Faust and grants him youth. Faust, in return, agrees that after he dies, he will serve the Devil in hell. The opera centers on the love story between the now young Faust and Marguerite, a beautiful village girl. At the end of the opera, Marguerite dies and a chorus of angels escorts her to heaven. The Devil then drags Faust down to hell.

In the 1800’s, the German composers Louis Spohr and Heinrich Zollner and the Italian composer Arrigo Boito also wrote operas based on the story of Faust and his agreement with the Devil. But Gounod’s version has become the most popular. The 1859 version had spoken dialogue. Gounod substituted recitative in a production first given in 1869, and that version is performed today. In Act III, Marguerite sings the beautiful “Jewel Song.” The lively “Soldiers’ Chorus” in Act IV is one of the best-known choral numbers in the entire repertoire.

Lucia di Lammermoor,

a tragic opera in three acts by Gaetano Donizetti. Libretto in Italian by Salvatore Cammarano, based on the Scottish novel The Bride of Lammermoor by Sir Walter Scott. First performed in Naples, Italy, in 1835.

Donizetti wrote Lucia di Lammermoor in the melodramatic style typical of Italian Romantic opera of the early 1800’s. The story takes place in Scotland in the late 1600’s. It concerns a doomed love affair between Lucia Ashton and Edgardo di Ravenswood. Enrico Ashton, Lucia’s brother, wrongfully holds Edgardo’s estate. To prevent Lucia and Edgardo from marrying, Enrico tricks Lucia into wedding another man. Lucia goes insane, kills her husband, and then dies. Edgardo hears of Lucia’s death and stabs himself to death.

The opera has one of the most dramatic ensembles in the repertoire, the sextet “Chi mi frena.” It is sung in Act II at Lucia’s wedding. But the opera is probably best known for the “Mad Scene” in Act III, in which the insane Lucia sings of an imaginary wedding between herself and Edgardo. This scene is considered one of the greatest challenges for a coloratura soprano in all opera.

Madama Butterfly,

a tragic opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini. Libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on the American play Madame Butterfly by David Belasco, from a story by John Luther Long. First performed in Milan, Italy, in 1904.

The story of Madama Butterfly takes place in Nagasaki, Japan, about 1900. Cio-Cio-San (Madame Butterfly) is a geisha (young Japanese woman trained to entertain men) who falls in love with an American naval officer, B. F. Pinkerton. They marry in a Japanese ceremony. According to Japanese law, either the husband or the wife may cancel the marriage on a month’s notice. Pinkerton must leave Japan with his ship. After he has left, the young woman gives birth to his child. Three years later, Pinkerton sends a letter saying that he has married an American. Shortly after the letter arrives, Pinkerton appears with his American wife. The heartbroken Cio-Cio-San agrees to give them the child. She then commits suicide.

Puccini tried to give Madama Butterfly an Oriental flavor by basing some of his score on Japanese music. He also included a passage from “The Star-Spangled Banner” in one of Pinkerton’s numbers. The opera’s best-known aria is the exquisite “Un bel di” in Act II. In it, Cio-Cio-San describes the happiness she will feel when Pinkerton returns.

Loading the player...Madama Butterfly: Un bel di

Magic Flute, The

(Die Zauberflote), a fairy-tale opera in two acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Libretto in German by Emanuel Schikaneder. First performed in Vienna, Austria, in 1791.

Mozart and Schikaneder were both members of a secret society called the Masons, and much of The Magic Flute deals symbolically with Masonic beliefs and rituals. However, the opera can be enjoyed as a fairy tale about two lovers, Tamino and Pamina. The opera takes its name from a magic flute that protects Tamino from danger.

Loading the player...The Magic Flute Overture

The opera has spoken dialogue instead of recitative. Some of the music resembles simple folk songs, though several of the arias are dramatic and solemn. The Queen of the Night, Pamina’s mother, sings two arias that are showpieces for a coloratura soprano. The arias have very hard passages and high notes. The overture is often performed as a separate work in concerts.

Marriage of Figaro, The

(Le Nozze di Figaro), a comic opera in four acts by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Libretto in Italian by Lorenzo da Ponte, based on the French play The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre de Beaumarchais. First performed in Vienna in 1786.

Beaumarchais wrote The Barber of Seville before The Marriage of Figaro. Mozart selected the second play for his opera. The Italian composer Giovanni Paisiello had already composed an opera based on The Barber of Seville. The same principal characters appear in both works. The plot of The Marriage of Figaro follows the action begun in The Barber of Seville. Mozart’s opera describes the problems that develop when Figaro, servant to Count Almaviva, tries to marry Susanna, Countess Almaviva’s maid. The Count wants Susanna for himself, but a final scene of multiple disguises brings him back to his wife.

Operagoers have praised The Marriage of Figaro for its vivid, realistic characters. Unlike many opera composers of the time, Mozart relied far more on ensembles than on arias to develop his characters.

Pagliacci

(The Players), a tragic opera in a prologue and two acts by Ruggero Leoncavallo. Libretto in Italian by the composer. First performed in Milan, Italy, in 1892.

A short Verismo opera, Pagliacci deals with life among members of a traveling company of actors in Italy in the 1860’s. The story concerns the jealousy of Canio, the leader of the players. The opera opens with a prologue sung in front of the curtain by Tonio, who plays a clown. The prologue announces the theme of the drama.

Early in Act I, Canio learns that Nedda, his wife, is unfaithful. He discovers she is having a love affair, but he does not know the identity of the man. Canio sings one of the great tenor arias in all opera, “Vesti la giubba,” which expresses his tragic fate of playing a clown while his heart is breaking. During a performance of a play, Canio learns that his wife’s lover is Silvio, a peasant who lives in the village where the actors are performing. Canio then stabs Nedda and Silvio as the opera ends.

Porgy and Bess,

a folk opera in three acts by George Gershwin. Libretto in English by Gershwin’s brother Ira and DuBose Heyward, based on Heyward’s novel Porgy. First performed in Boston in 1935.

Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess is one of the few American operas that has achieved worldwide fame. The opera portrays life among black people in Charleston, S.C., in the 1920’s. It specifically deals with the love of the crippled Porgy for the beautiful Bess. The story is colorful and highly dramatic, and it has considerable humor. In his score, Gershwin captured the flavor of the songs sung by black people of the Southeastern United States.

The opera consists largely of individual songs and choral scenes, connected by recitative. Only the white characters have spoken dialogue. Some of the songs, including “Summertime,” “I Got Plenty o’ Nuttin’,” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So,” have become popular hits.

Rigoletto,

a tragic opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi. Libretto in Italian by Francesco Maria Piave, based on the French play Le Roi s’amuse (The King Is Amused) by Victor Hugo. First performed in Venice, Italy, in 1851.

The opera tells a story of treachery and revenge in the court of an Italian nobleman, the Duke of Mantua, in the 1500’s. The chief characters include the duke; Rigoletto, a hunchback who is the duke’s jester; and Gilda, Rigoletto’s daughter. Through intrigue and deceit, Rigoletto’s beloved daughter is murdered.

For Rigoletto, Verdi composed some of his most glorious melodies. In Act I, Gilda sings the beautiful aria “Caro nome,” in which she expresses her love for the duke, who is disguised as a student. In Act III, the duke sings one of the most popular arias in the repertoire, “La donna e mobile.” The aria is an ironic comment by the faithless duke on how changeable women are in their affections. The emotional and melodic quartet “Bella figlia dell’ amore” is sung later in Act III.

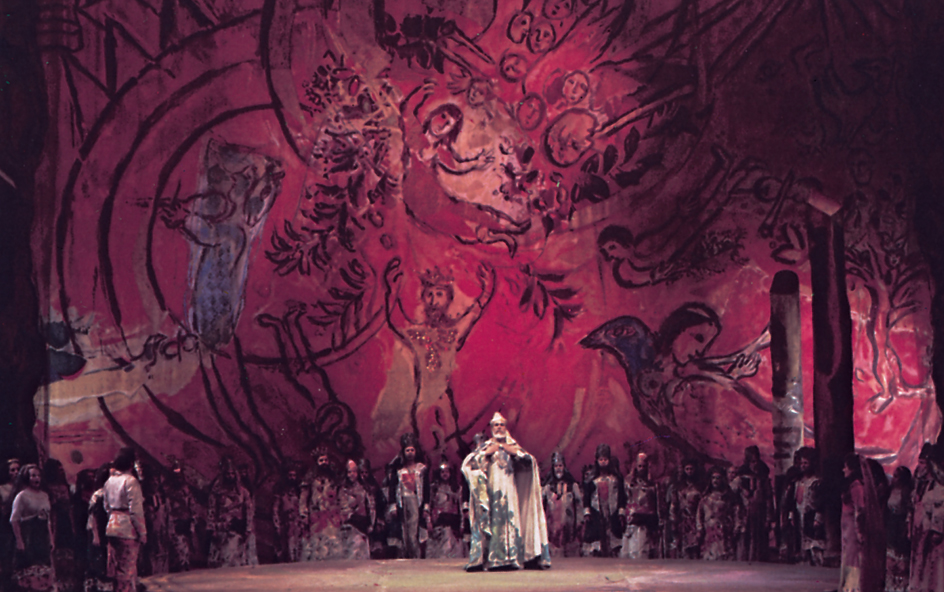

Ring of the Nibelung, The

(Der Ring des Nibelungen), a cycle of four operas by Richard Wagner. Libretto in German by the composer. The three main parts are Die Walkure (The Valkyrie, 1870); Siegfried (1876); and Gotterdammerung (Twilight of the Gods, 1876). Wagner called the fourth work, Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold, 1869), the prologue to the other three. However, it is a complete opera. All four works were first performed as a cycle at the opening of the Festival Opera House in Bayreuth, Germany, in 1876.

The four operas have a continuous plot based on ancient German and Icelandic legends. The Rhinemaidens guard a treasure of gold on the bottom of the Rhine River. Alberich, one of a group of dwarfs called Nibelungs, steals the Rhine gold and makes a ring from it. The ring gives magic powers to whoever possesses it. After the ring is stolen from Alberich, he puts a curse on it. The ring changes owners several times during the four operas.

Loading the player...The Ring of the Nibelung: The Valkyrie

Many gods and goddesses take part in the action, including Wotan, their chief; and Fricka, his wife. Other important characters include Brunnhilde, one of several female warriors called Valkyries; Siegmund, a mortal son of Wotan; Siegfried, Siegmund’s son; and Sieglinde, Siegmund’s sister. The Ring cycle deals with the decline and downfall of the gods, brought about by their greed and lust for power as represented by the ring.

Rosenkavalier, Der

(The Cavalier of the Rose), a partly comic, partly serious opera in three acts by Richard Strauss. Libretto in German by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. First performed in Dresden, Germany, in 1911.

Unlike most opera texts, the libretto for Der Rosenkavalier is an outstanding work of literature. It glamorously portrays life among the aristocracy in Vienna in the 1700’s. In most productions, the sets for the first two acts are spectacular, representing luxurious Viennese palaces. The work also calls for magnificent costumes.

The opera describes the love affairs of four chief characters: Princess von Werdenberg, called the Marschallin; Octavian, a young nobleman; Sophie, a beautiful girl; and Baron Ochs, a coarse and comic country nobleman. Strauss wrote the role of Octavian to be played by a female, and a mezzo-soprano sings the part.

Strauss composed many brilliant ensemble scenes for Der Rosenkavalier. One of the most impressive takes place in Act I when the Marschallin receives many visitors. The composer emphasized the lighthearted Viennese quality of the opera in a number of lilting waltzes. These waltzes are sometimes performed separately in concerts.

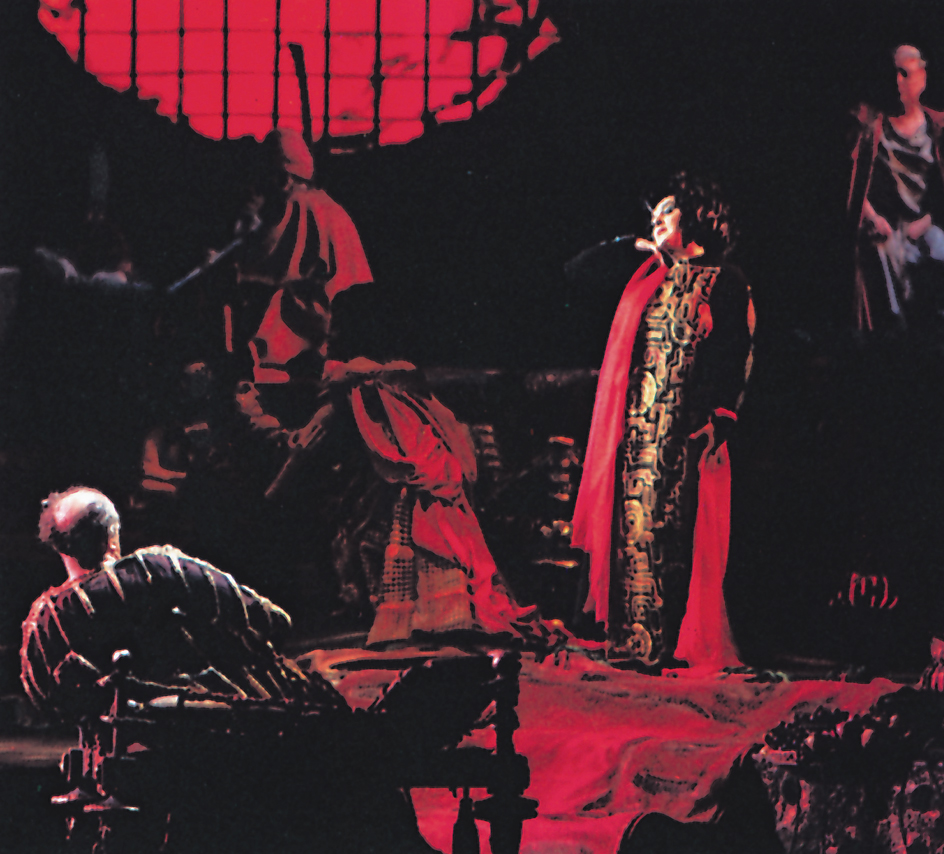

Salome,

a tragic opera in one act by Richard Strauss. Libretto in German by Hedwig Lachmann; a translation of a play in French, Salome, by the Irish-born author Oscar Wilde. First performed in Dresden, Germany, in 1905.

Wilde based his play on the story of Salome in the New Testament, but he invented many details that shocked audiences of his time. In Wilde’s play, Salome, a 15-year-old girl, is attracted to the religious prophet Jochanaan (John the Baptist). After Jochanaan rejects her advances, she decides to take revenge. Salome’s stepfather, King Herod, asks her to dance for him and, in return, promises her anything she wishes. Salome performs the famous “Dance of the Seven Veils” and then asks Herod for Jochanaan’s head on a silver dish. Herod, though horrified, keeps his promise and has Jochanaan beheaded. Salome kisses the head of the prophet, an act that audiences of the early 1900’s considered especially objectionable.

Strauss’s score captures perfectly the mood of Wilde’s gruesome story. The music is often violent and harsh. At other times, it is vigorous and passionate. The orchestral music especially helps create the rich Oriental atmosphere of the opera. The role of Salome is one of the most difficult in the repertoire. The performer must not only sing extremely complicated music, but she must also act and dance well. In addition, she should look young and beautiful.

Tosca,

a tragic opera in three acts by Giacomo Puccini. Libretto in Italian by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on the French play La Tosca by Victorien Sardou. First performed in Rome in 1900.

The story of Tosca takes place in Rome in 1800, when the city is torn by political intrigue. The chief characters are Floria Tosca, a famous singer; Mario, a painter and Tosca’s lover; and Baron Scarpia, the villainous chief of police. In the story, Cesare Angelotti, an escaped political prisoner, has fled from Scarpia. Both Tosca and Mario know Angelotti’s hiding place. Much of the action concerns Scarpia’s attempts to force Tosca and Mario to reveal where Angelotti is hiding. Scarpia also wants to make Tosca his mistress. Tosca kills Scarpia and then commits suicide after she watches a firing squad execute Mario.

Puccini’s music powerfully expresses the passion and violence of the plot. The work also has several beautiful melodies, including Tosca’s “Vissi d’ arte” in Act II and Mario’s “E lucevan le stelle” in Act III.

Traviata, La

(The Wayward Woman), a tragic opera in three acts by Giuseppe Verdi. Libretto in Italian by Francesco Maria Piave, based on the French play The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas the Younger. First performed in Venice, Italy, in 1853.

Although La Traviata failed dismally at its premiere, it has become one of the most frequently performed works in the repertoire. Verdi set the action in and near Paris in the mid-1800’s. The opera shocked many people during the mid-1800’s because Violetta, its heroine, leads an immoral life.

Unlike many earlier operas, La Traviata has realistic characters with complicated emotions. Their thoughts and feelings seem especially convincing because of Verdi’s theatrically effective music. For example, in Act I, Violetta tries to decide whether to fall in love with Alfredo, who loves her. The music clearly reflects her indecision. In Act III, she sings one of the opera’s most haunting arias, “Addio del passato,” in which she bids farewell to the happy days of the past.

Loading the player...Addio del passato from La Traviata

Trovatore, Il

(The Troubadour), a tragic opera in four acts by Giuseppe Verdi. Libretto in Italian by Salvatore Cammarano, based on the Spanish play El Trovador by Antonio Garcia Gutierrez. First performed in Rome in 1853.

Like most Verdi operas, Il Trovatore tells a gloomy and violent story filled with passion. The action takes place in Spain in the 1400’s. The principal characters include Manrico, a troubadour (poet-musician); Leonora, a noblewoman; Azucena, a Gypsy; and the Count di Luna. Manrico and Leonora are lovers, but the count also loves Leonora. In addition, di Luna and Manrico are brothers, though only Azucena knows it. Azucena seeks revenge against the count because his father had her mother burned at the stake. By the opera’s end, Leonora has committed suicide and the count has executed Manrico. After Manrico’s death, Azucena tells the count he has killed his brother, and she thus has her revenge.

Despite a frequently confusing plot, Il Trovatore is brilliantly effective theater. The opera also has some of Verdi’s most memorable music. In Act II, a band of Gypsies in their mountain camp sings what is perhaps the most familiar choral number in all opera, the stirring “Anvil Chorus.”

Loading the player...Anvil Chorus from Il Trovatore

Wozzeck,

a tragic opera in three acts by Alban Berg. Libretto in German by the composer, based on the German play Woyzeck by Georg Buchner. First performed in Berlin in 1925.

Wozzeck is a private in the Austrian army about 1830. His superiors abuse and ridicule him. Even worse, Marie, the woman he loves, deceives him with another man. Driven almost insane by jealousy, Wozzeck stabs and kills Marie. Later, he throws the knife into a pond. Finally, he drowns while searching for the knife.

Much of the text for Wozzeck is set in an intensely emotional vocal style midway between spoken dialogue and singing. This style is known by the German term Sprechstimme (speaking voice). Most of the music is atonal—that is, it does not fall into the traditional keys.

Although Wozzeck is difficult to sing and play, it has been performed in many countries. Some people consider the music jarring and too hard to understand. But others feel that it powerfully expresses a great variety of emotions.