Oyster is a type of shellfish that people harvest for food and pearls. The soft, edible body of an oyster is protected inside a hard, two-piece shell. The shell is usually irregular in shape. An oyster spends all except the first few weeks of its life attached to hard surfaces on the seabed. Oysters live in relatively calm waters of mild to tropical coastal oceans. They often form large reefs.

People began eating oysters thousands of years ago. About 100 B.C., the ancient Romans raised oysters on “farms” along the coast of Italy. Today, oysters are farmed along coasts of the United States, Europe, and East Asia.

Oysters—like clams, scallops, and some other shellfish—are a type of mollusk, a group of soft-bodied animals that have no bones. Oysters are called bivalve (two valve) mollusks because their shell is made up of two parts called valves.

There are several different groups of oysters. One group includes pearl oysters, which produce high-quality pearls. The oysters most often eaten by people are known as true oysters. They are the most abundant and well-known group. This article chiefly deals with true oysters.

The body of an oyster

Shell.

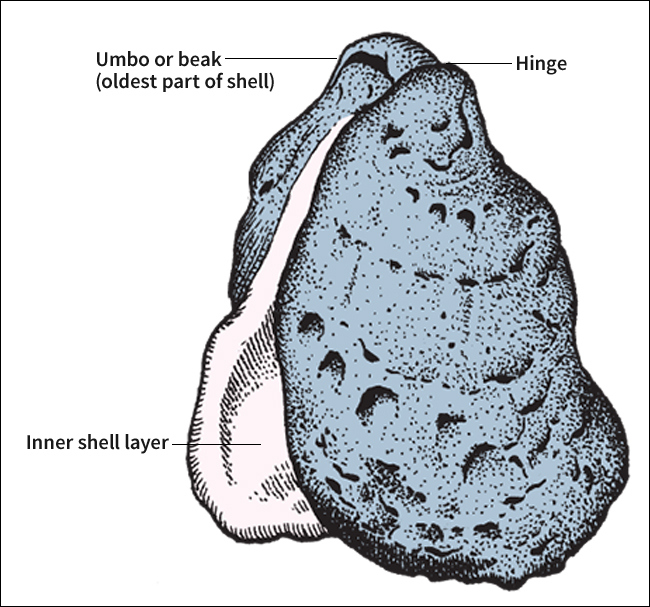

The valves of an oyster’s shell are held together at the hinge by an elastic ligament. A ligament is a band of stringy fibers. One valve is deeper, larger, and thicker than the other. This large valve is the one that the animal normally fastens to the ocean bottom.

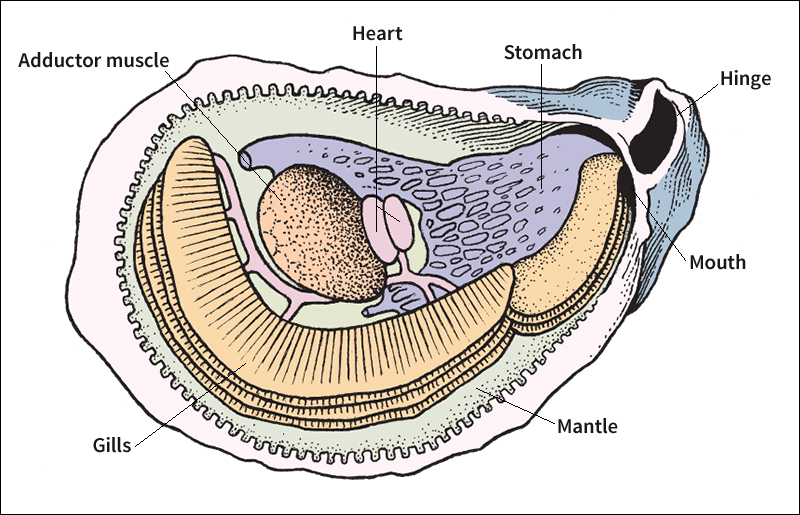

The elastic ligament usually keeps the valves slightly apart. A strong muscle called an adductor closes the shell. When threatened or during long periods out of the water, oysters close their valves tightly. They can live with their shell closed for several weeks.

An oyster’s shell is made of a hard, chalky material called calcium carbonate. The shell is produced by a skinlike organ called the mantle, which lines the inside of the shell. The mantle takes minerals from food the oyster eats and directly from seawater. It uses these minerals to produce the shell. Because the mantle makes shell in cycles, periods without shell growth leave a line. Shell lines can be used like the rings of a tree to estimate the age of an oyster. The shell grows as long as the oyster’s body grows.

The inside of the shell is white with colored highlights. The shell of a pearl oyster is lined with a smooth, shiny substance called mother-of-pearl. A scar inside the shell indicates where the adductor muscle was attached.

Sometimes a piece of grit or other substance becomes caught between the mantle and the shell, irritating the mantle. The irritation stimulates the production of a pearl. Shell material is evenly laid down around the particle to stop the irritation. In this way, a pearl is formed. Pearl oysters can produce high-quality pearls and are the primary source of pearls. True oysters rarely produce pearls. When they do, the pearls are dull in color, irregular in shape, and of little value.

Body organs.

An oyster, like all bivalves, does not have a head. A pair of W-shaped gills is located beneath the mantle. The oyster uses its gills to breathe. Also, the gills are covered by fine, hairlike cilia. Water flow created by the cilia brings single-celled plantlike organisms called phytoplankton toward the gills. The cilia direct the food to the mouth. The food then moves into the oyster’s stomach. The oyster’s heart pumps blood to the parts of its body. A pair of kidneys removes wastes.

An oyster has a simple nervous system made up of a few nerve bundles and connecting nerves. An oyster does not have eyes. However, it does have two rows of sensitive tentacles (feelers) along the mantle edge that can sense changes in light, chemicals in the water, and water currents. Any change will cause the tentacles to contract (become smaller). In response, the adductor muscle quickly closes the shell against possible danger.

The life of an oyster

Many kinds of oysters are hermaphrodites << hur MAF ruh dyts >>—that is, animals with both male and female reproductive organs. Certain oysters begin their life as males but later develop into females. Other kinds alternate between male and female several times during their lives. During the female stage, various oysters can produce more than 100 million eggs each year. Male oysters release sperm, which fertilize the eggs. In many oysters, the eggs are fertilized after the female releases them into the water. In others, the sperm enter the female’s body to fertilize the eggs.

Young.

An oyster begins life drifting as part of the mass of tiny organisms called plankton. An oyster larva develops from the fertilized egg. After a day, the larva is called a veliger << VEE luh juhr >>. Veligers use their cilia to move. A tiny bivalve shell is visible.

Veligers swim in the water for about two weeks. During this time, the animal continues to develop and forms a muscular “foot” that extends between the valves. The animal is now called a pediveliger << `pehd` uh VEE luh juhr >>. The foot is used to test different surfaces as the oyster searches for an appropriate site to settle. An oyster usually chooses a hard surface, such as a rock or the shell of another animal. It then attaches itself permanently to the surface using cement produced by its body. Most pediveligers settle with adult oysters, and together they often form crowded beds (groups) in coastal waters. They sometimes form large reefs.

Young oysters lose their foot shortly after they settle. A month-old oyster is about the size of a pea. A year-old oyster is approximately 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) in diameter. Oysters usually grow at a rate of an inch per year for three or four years. After this time, their growth rate slows. Some oysters grow as large as 14 inches (36 centimeters). Most oysters live about 6 years, but some can survive more than 20 years.

Predators.

Many predators (hunting animals) feed on oysters. Also, diseases caused by various viruses and protozoa (single-celled organisms) can kill millions of oysters in a single year.

Most newly hatched oysters are eaten by predators, including fish and comb jellyfish. Once settled, even adult oysters fall prey to many animals. Starfish use their tube feet to pull at the oyster’s valves, which eventually causes the shell to open slightly. The starfish then eats the soft oyster meat. Some crabs with powerful claws can crack the shells of small oysters, as can some fish with strong jaws. An oyster-drill snail uses secretions and its filelike tongue to make a hole in an oyster’s shell. The snail then sucks out the oyster meat. Such birds as the oystercatcher can pry an oyster’s shell apart with their strong beaks.

People are the greatest predators of oysters. They collect and eat millions of oysters each year. Overfishing and pollution have reduced the stock of oysters.

Oysters and ecosystems

Oysters may form large reefs. These reefs are made up of several generations of oysters attached one on top of another. Oyster reefs can rise above the seabed for 10 to 12 feet (3 to 4 meters). They may cover several acres or hectares. These reefs are important to many ecosystems. An ecosystem includes the things that live in an area as well as their relationships with one another and their environment. Oyster reefs were once much larger than they are today. But they have diminished as a result of human activities, including overfishing and pollution.

Oyster reefs and biodiversity.

Oyster reefs provide habitat for many marine organisms. Barnacles, anemones, sea squirts, and other animals attach to the shells of living oysters. Several kinds of fish use empty oyster shells as nesting sites. Some animals hide from predators on oyster reefs. Others come to oyster reefs to feed. The result is that oyster reefs support biodiversity—that is, the variety of living things.

Water quality.

Oysters filter large volumes of water to remove phytoplankton for food. In the process, they remove nutrients from the water. In many areas, coastal waters are polluted by excess nutrients. This pollution results mainly from human activities, especially agriculture. Water filtration by oysters and other bivalves helps to reduce this pollution. This filtration also makes the water clearer, allowing sunlight to reach greater depths. In this way, oysters improve the quality of the water for other living things.

Reef conservation and restoration.

Overfishing and pollution have severely damaged many oyster reefs. As much as 85 percent of natural oyster reef habitat has been destroyed by human activities in about the last 150 years. Scientists and conservation groups are working to restore oyster reefs in many areas.

The oyster industry

Oyster farming.

The popularity of oysters as food—and the threat to their natural populations—has led to the growth of oyster farming. Most oyster farms are established in shallow, quiet coastal waters where there is a firm ocean bottom. Shifting sand or mud can cover and smother oysters. Floats mark a farmed area. Oyster farmers place old shells or tiles on the bottom or suspended in the water. These materials act as cultch, a surface to which the young oysters can attach themselves. In areas where oysters do not settle naturally, farmers often buy seed oysters to “plant” in the farming areas. Some oyster farmers spawn oysters and grow the veligers in tanks of seawater. Following settlement, the juvenile oysters are grown in flowing seawater for several weeks. Then, they are planted in coastal waters to finish growing. Workers harvest the crop when the oysters are 2 to 4 years old and 2 to 4 inches (5 to 10 centimeters) in diameter.

Many oysters raised for market come from commercial oyster farms. Large oyster-farming centers include those along the southwest coast of France and the west coast of the United States. China, South Korea, Japan, the United States, and France are the leading oyster-producing countries.

Oyster harvesting

is heaviest during fall and winter in most regions. Farmers use long tongs to collect oysters in shallow waters. In deeper waters, they gather the oysters with dredges, which are nets attached to metal frames. The dredges are attached to a boat by a line and dragged along the bottom.

Oyster meat.

People eat oysters fried, broiled, scalloped (baked in sauce), and prepared many other ways. Oysters are rich in protein and in several minerals and vitamins. But the U.S. Food and Drug Administration advises that people with diabetes, weakened immune systems, or other medical conditions should avoid eating raw oysters. People once believed that oysters were unsafe to eat during months without an r in their name—that is, from May to August. Scientists now know that oysters spawn (produce eggs) during summer. Oysters are less tasty when they are spawning, but they are safe to eat.