Paint is a substance that colors and protects a wide variety of surfaces. It is used on the inside and outside walls of buildings, on automobiles, on furniture and household appliances, and on many machines and machine parts. Most paints go on as liquids and then dry to form a thin solid film. A typical coat of paint is about 3/1,000 inch (0.08 millimeter) thick.

Paint consists of one or more finely ground pigments and a liquid vehicle. Pigments determine the color of the paint and provide it with certain other properties. Pigments commonly used for their color include titanium dioxide (white), iron oxide (yellow or red), phthalocyanine (blue or green), and toluidine (bright red). Manufacturers often add clay, mica, and talc to paint to increase its resistance to wear. These semitransparent materials are called extenders or inert pigments. Such pigments as zinc phosphate and barium metaborate help paint protect metal surfaces against rust. Pigments composed of fine metal powders give surfaces a metallic finish.

A paint’s vehicle carries the pigment and binds it to a surface. Paint vehicles are composed of one or more resins and a solvent. Resins are sticky substances obtained from plants or manufactured through chemical processes. They are the main ingredient in paint. People often refer to paints by their resin type. Resins include acrylics, alkyds, epoxies, and polyurethanes. Resins largely determine the adhesive quality, drying time, gloss, and hardness of paints. Most are nearly colorless.

The solvent is the ingredient that makes paint a liquid. The solvent depends on the resins used. Most household paints, and an increasing number of industrial paints, use water as a solvent. Other commonly used solvents include mineral spirits, ketones, glycol ethers, and xylene. Solvents are sometimes called paint thinners. Vapors given off by some solvents can threaten a user’s health, contribute to air pollution, and even play a part in the thinning of the protective layer of ozone in the upper atmosphere. The governments of many countries regulate the use of solvents in paints.

Kinds of paint

There are many kinds of paint. Chemists often classify paints according to the way they cure (dry and harden). For example, some paints cure simply through the evaporation of the solvent, which is accompanied by the hardening of the resin. Others form a solid film only after a chemical called a catalyst has triggered a reaction to bond the resin particles together. This reaction follows the evaporation of most of the solvent.

Paints are also grouped according to their use. For example, household paints decorate and protect houses, office buildings, and other structures. Industrial paints are used on a wide variety of consumer products and industrial equipment.

Household

paints include paints for the walls, ceilings, floors, and exteriors of buildings. They are sometimes called architectural paints.

Most household paints are latex paints. Latex (natural rubber) was emulsified (evenly distributed) and used as the resin in early water-based paints—that is, paints that use water as a solvent. Polyvinyl acetate or acrylic resins have replaced latex in such paints, but these coverings continue to be called latex paints. Latex paints cure by coalescence. In this process, the resin molecules bond together to form a dry paint film. This bonding occurs as the water evaporates from the painted surface.

Latex paints are not flammable and have little odor. They dry to a film that can be easily cleaned with soap and water. Interior latex wall paints can tolerate repeated washings, but they are not durable enough for surfaces exposed to the weather. Sunlight can fade paint. Wind, rain, and extremely hot or cold temperatures can cause paint to crack, chip, blister, and peel. As a result, exterior house paints have been developed with resins that provide increased resistance to weathering.

Most exterior house paints are latex paints. But some are oil-based—that is, they contain resins and solvents obtained from petroleum products, vegetable oils, or linseed or other seed oils. Oil-based paints cure by oxidation. After most of the solvent has evaporated, the resins combine chemically with oxygen in the air to form a hard film.

Special paints called primers, sealers, or undercoaters are used when painting such porous surfaces as bare wood or plaster. Primers are applied as the first coat to form a smooth base for the final coat of paint.

The United States government restricts the content of lead pigments in household paint to 0.06 percent by weight of the dried film. This restriction was first applied in 1977, after the discovery that some children had developed lead poisoning after being exposed to paint with a high lead content. The affected children ate chips of dried paint with a high lead content, or swallowed or inhaled dust containing particles of this paint.

Industrial paints

are used on such consumer products as automobiles, furniture, and household appliances. They also include coatings that protect machinery and other industrial equipment against moisture, strong chemicals, rust, and extremely high temperatures.

Most automobile manufacturers paint their cars with highly specialized coatings that contain acrylic resins and cure when they are baked on. Many kitchen and laundry appliances also have baked-on finishes. Such coatings produce an extremely hard surface that is resistant to harsh chemicals and does not dull or fade easily.

Manufacturers of wooden furniture often use wood stains on their products. The pigments in wood stains are highly transparent. They are dissolved in a vehicle that enables the stain to soak into the wood rather than stick to its surface as a film. Stains darken the color of wood but allow the wood grain to show through. After staining wood, manufacturers apply a clear, protective finish, often using lacquer or shellac. These finishes cure by solvent evaporation—that is, the resins solidify into a hard coat as the solvent evaporates. These finishes dry quickly and produce a shiny surface. After they have hardened, such finishes can be redissolved with the same solvents originally used in the vehicle. Manufacturers finish some wood products with varnish, a clear, oil-based coating that dries by oxidation.

Iron and steel may rust if they come in contact with moisture and oxygen. For this reason, manufacturers coat many products made of iron or steel with special rustproof primers and finish coats. Metal primers have high proportions of rust-resistant pigments. Some of these paints contain ingredients that penetrate rust to drive out oxygen and moisture. Finish coats cover the metal primer and seal it. In general, the primer protects the metal and the finish coat protects the primer. Manufacturers cover some metal products with enamels, which contain alkyd resins and dry by oxidation.

The most durable coatings available are generally used on machinery and other industrial equipment. They are often based on epoxy or polyurethane resins, which cure by chemical reaction. The chemical industry uses a number of such paints to protect the surfaces of pipes and containers that are used to store or carry harsh chemicals. Chemical companies have developed special heat-resistant coatings for high-speed aircraft, space vehicles, and equipment used in certain industrial processes. Some of these special paints can withstand temperatures as high as 1200 °F (650 °C).

How paint is made

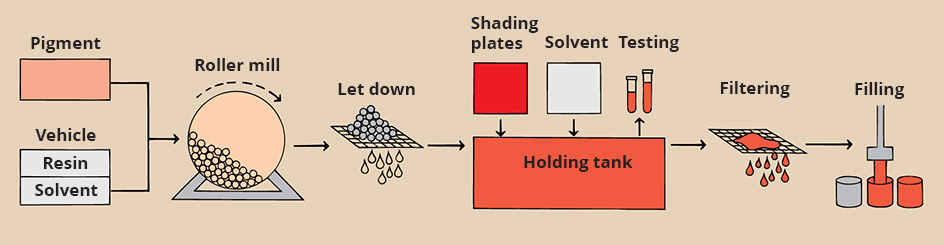

All paints are manufactured according to a similar process. The basic steps of this process are (1) grinding, (2) let down, (3) shading, and (4) thinning.

Grinding.

Batches of paint vary in size, but many batches are as large as 1,500 gallons (5,700 liters). To produce a batch of paint, manufacturers first load an appropriate amount of pigment, resin, and liquid chemicals into one of several types of grinding mills. The mill grinds the liquid and dry ingredients into a fine, uniform material called mill paste.

Manufacturers choose a mill according to the hardness of the pigments and the fineness of grind required for the paint. Latex house paints are usually prepared in a mill called a high-speed disperser. This mill has circular blades with saw-toothed edges. The blades rotate at high speeds, causing the pigment particles to collide with one another and break into smaller pieces.

Other mills have a large, rotating steel cylinder partly filled with pellets or particles called grinding media. Ball mills contain steel balls that measure about 5/8 inch (1.6 centimeters) in diameter. Pebble mills contain flattened ceramic balls about 13/8 inches (3.5 centimeters) in diameter. As the mill turns, the grinding media tumble against one another, crushing the pigment between them. Most of these mills rotate at about 16 revolutions per minute. The grinding process may last 24 hours.

Sand mills or bead mills can produce fine grinds faster than other mills. These mills shoot tiny glass beads through the pigment at high speeds. The mills can supply finely ground paste continuously or in batches.

Let down.

After grinding the pigment, the paint maker adds more resin to the paste in the mill, along with a small amount of solvent. The paste is then “let down”—that is, it is pumped out of the mill through a strainer to a holding tank. The strainer removes the grinding media or other foreign matter from the paste. Workers rinse the mill with more solvent, which is then mixed with the rest of the material in the holding tank.

Shading,

also called tinting, probably requires more care than any other step in the manufacturing process. In this step, paint producers compare samples of the material in the holding tank with color standards they keep on file. They then add small amounts of shading paste to the batch to adjust its color to the standard. Shading pastes are highly concentrated blends of ground pigments and a vehicle.

Thinning.

After the batch has been shaded to specification, the paint maker thins it to the desired viscosity (thickness) by carefully adding solvent to it. Manufacturers then test the final product for quality. Finally, they filter the paint and pour it into containers for shipment.

How to use household paint

Selecting the paint.

Household paint comes in flat, semigloss, and gloss finishes, and in a wide variety of colors. The nature of the surface to be covered plays an important role in choosing the finish and color of paint. For example, a single coat of paint is often sufficient when covering a similar color. But two or more coats may be required when painting over a different color. Flat paints, also called dull or matte paints, help hide flaws on surfaces. Gloss finishes, on the other hand, are smooth and shiny, and they readily show any surface defects. However, gloss paints are more durable than flat paints. Paints with intermediate levels of gloss are often called eggshell, satin, or velvet.

Preparing the surface.

Poor surface preparation is the most common cause of paint failure. For paint to stick properly, the surface to be painted must be free of dirt, dust, grease, loose paint, moisture, oil, and wax. Often, washing a surface with soap and water is sufficient. But some surfaces may require scraping, brushing with a wire brush, or sanding. Others may also have cracks or holes that should be filled and sealed.

Stirring and filtering.

Paint often settles. Always stir paint before applying it to ensure that it has a uniform consistency. One of the best methods is to stir in a figure-eight motion with a paint paddle. Lift the paddle occasionally to raise heavy pigments from the bottom of the can. Before painting, many people strain paint through a special paint filter, a fine screen, or a nylon stocking. This procedure is especially helpful when using old or leftover paint, which might contain dirt, rust from the can, or pieces of dried paint film.

Applying the paint.

Paint may be applied with brushes, spray equipment, rollers, or paint pads. Small objects and irregular surfaces can best be painted with brushes or sprayers. Large, flat surfaces can be painted faster with sprayers, rollers, or paint pads.

Brushes are made of hog bristles or synthetic fibers. Hog-bristle brushes are used to apply oil-based paints. Synthetic-fiber brushes may be used to apply either oil-based or latex paints. To prevent streaking, spread the paint on a dry area and then brush it toward the wet edge of a previously painted area.

Spray painting produces a smooth coat of paint. Spray-painting equipment causes thinned paint to form droplets under pressure. When spraying paint, wear filter masks to avoid inhaling paint mist and vapor. Cover all surfaces that are not to be painted to protect them from the fine spray.

Rollers hold paint in fibers, the length of which determines the nap of the applicators. Rollers with short naps are suitable for applying thin paints on smooth surfaces. Long-napped rollers work better for thicker paints and textured surfaces. To produce an even coat, roll paint onto the surface in crisscross and up-and-down strokes. Each rolled strip of paint should overlap the wet edge of the previously painted area to avoid streaks.

Paint pads are made of foam, mohair, or synthetic fibers. They hold a large amount of paint and apply smooth coats of paint.

The history of paint

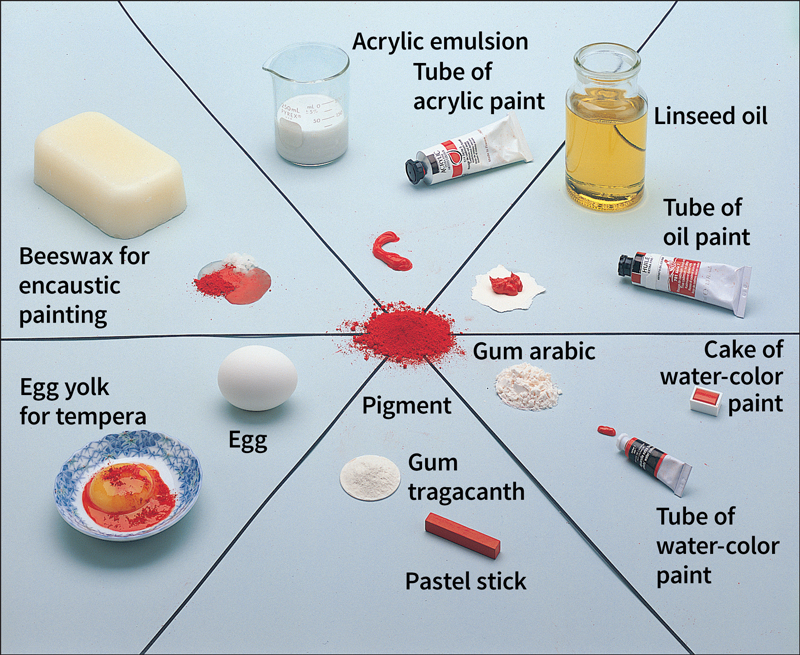

Prehistoric people made paints by mixing vegetable and earth pigments with water or animal fat. They painted on cave walls, on tombs, and on their bodies. Some caves in western Europe have walls that were painted about 30,000 years ago.

By 2000 B.C., the Egyptians painted tombs with materials similar to paints made today. These paints were made of crudely refined pigments, natural resins, and drying oils. The Egyptians imported pigments from as far away as India. By 1500 B.C., painting and paint making had become known in Crete and Greece.

The Romans learned how to make paints from the Egyptians. After the fall of the Roman Empire in the A.D. 400’s, paint making became a lost art until the English began making paints near the end of the Middle Ages. They used paints chiefly on churches at first, and later on public buildings and the homes of wealthy people.

During the 1400’s and 1500’s, Italian artists and craftworkers developed their own paint-making processes. Unfortunately, they kept their formulas secret, and so the process of making a particular paint often died with its inventor.

The commercial manufacture of paints began in Europe and the United States during the 1700’s. The early manufacturers of paint ground their pigments on a stone table with a round stone. The American colonists made their own paints using such materials as eggs, coffee grounds, and skim milk. They thinned these paints with water. In the late 1800’s, grinding and mixing machines were developed that enabled manufacturers to produce large volumes of paint.

Improvements in paint technology closely paralleled advances in chemistry during the 1900’s. Chemical companies developed many synthetic resins and a number of new pigments. Paints became increasingly specialized to meet the specific demands of industry.