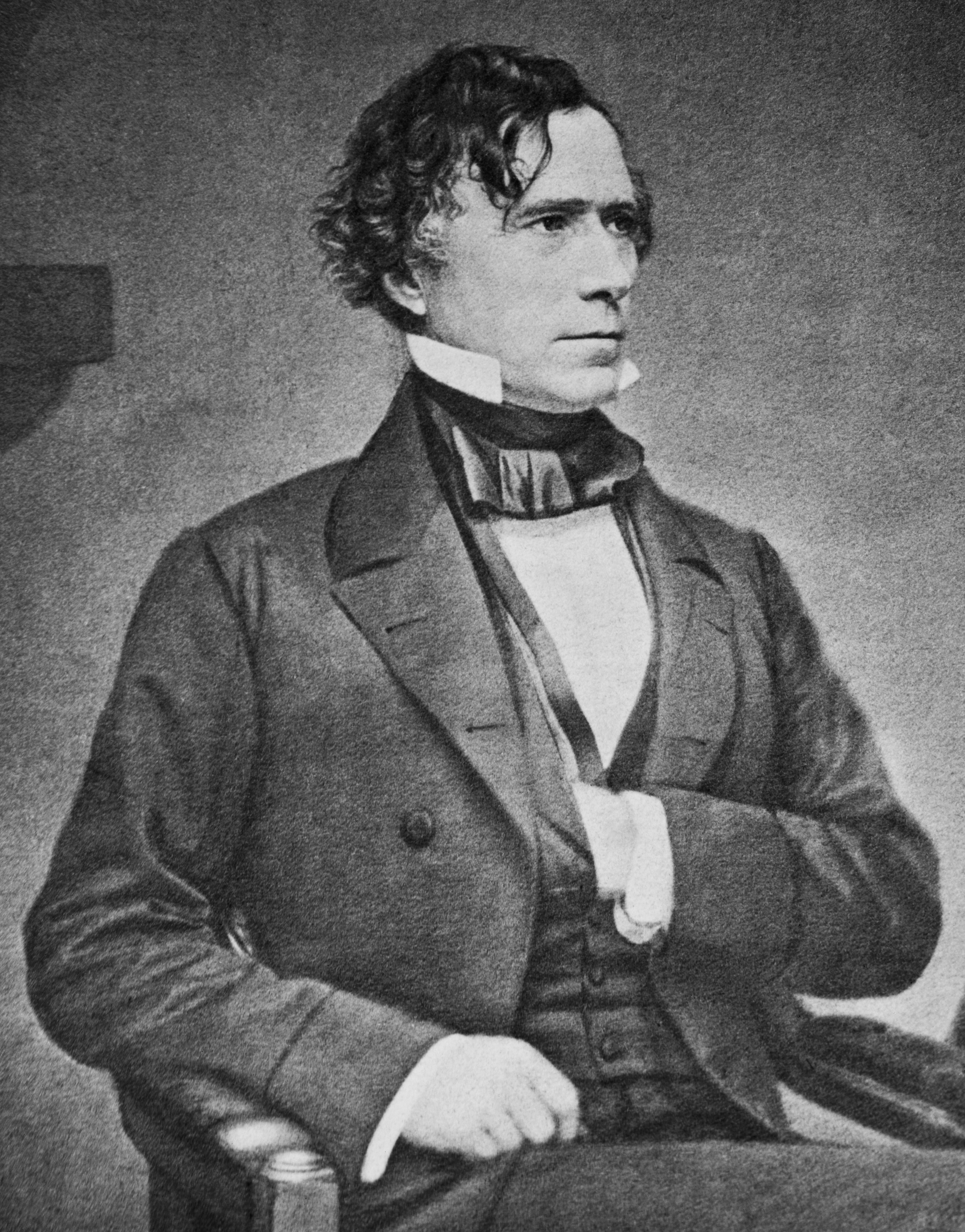

Pierce, Franklin (1804-1869), served as president during a period of increasing bitterness between North and South that later led to the American Civil War. He won the Democratic nomination for president in 1852 after the four strongest candidates had fought to a stalemate. Pierce gained support because he strongly favored the Compromise of 1850, which sought to settle the slavery dispute. “If the compromise measures are not … firmly maintained,” he said, “the Constitution will be trampled in the dust.” At 48, Pierce became the youngest president of the United States up to that time.

Pierce’s good looks and brilliant speaking manner impressed all who met him. People in New Hampshire respected his service as a U.S. representative and senator, and as a brigadier general in the Mexican War (1846-1848). But few people outside his home state had heard of Pierce until he ran for president.

As president, Pierce faced two difficult problems: (1) growing Northern opposition to any expansion of slavery, and (2) rising prejudice against immigrants. He angered Northerners by supporting the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which made slavery possible in a large area of the West. This act provided the issue that created the Republican Party. Pierce stirred up further opposition when he protected the rights of immigrants. Those opposed to granting rights to immigrants also formed a new party, called the Know-Nothing, or American, Party. By the time Pierce’s term ended, the Democratic Party had lost much of its strength. Few Democrats favored Pierce for reelection.

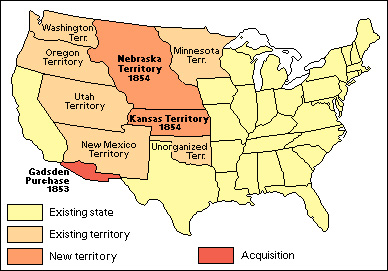

Pierce’s Administration marked one of the most prosperous periods in American history. The California gold rush, which began in 1848, still attracted people westward. Federal grants of land spurred railroads to extend their lines westward. And the Gadsden Purchase added land from Mexico to the Territory of New Mexico. The literary world discussed major new works such as Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha, and Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Songs such as Stephen Foster’s “My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night” became popular.

Early life

Franklin Pierce was born in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, on Nov. 23, 1804. His father, Benjamin Pierce, had served in the American Revolution (1775-1783) and later became a brigadier general in the state militia. The elder Pierce served two terms as governor of New Hampshire. Franklin spent a happy childhood with his six older and two younger brothers and sisters.

At the age of 11, the boy was sent to the academy in nearby Hancock. Friends recalled that just after Franklin entered the school, he became homesick and returned home on foot. His father put him into a wagon, drove him halfway back to the academy, and left him at the roadside, never saying a word. The boy trudged the remaining 7 miles (11 kilometers) back to school. A year later, he transferred to the academy at Francestown, New Hampshire, and later to Phillips Exeter Academy. In 1820, he entered Bowdoin College, where he became a close friend of undergraduate Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Pierce spent much of his college life in social activities. He joined literary and political clubs and became active in debating groups. At the end of his second year, Pierce’s marks were the lowest in his class. He then settled down to study. Pierce ranked third in his class when he graduated in 1824.

Political and public career

Pierce began studying law under Governor Levi Woodbury of New Hampshire. He later studied under Judge Samuel Howe and Judge Edmund Parker. In 1827, Pierce opened his own law office in Concord, New Hampshire.

Entry into politics.

Pierce supported Andrew Jackson’s campaign for the presidency. In 1829, he won election to the New Hampshire House of Representatives. He was reelected two years later and became speaker of the House. In 1833, Pierce won a seat in the United States House of Representatives. After serving two terms he was elected to the United States Senate. At 32, he became the youngest senator.

Pierce’s family.

Pierce’s years in Congress were not happy. In 1834, he had married Jane Means Appleton (March 12, 1806-Dec. 2, 1863), whose father had been a Congregational minister and president of Bowdoin College. Mrs. Pierce suffered from tuberculosis. She disliked Washington and seldom accompanied her husband to the capital. Pierce finally agreed to his wife’s wishes and resigned from the Senate in 1842, shortly before his term ended. Mrs. Pierce’s natural shyness deepened to melancholy after two of their three sons died in early childhood.

Soldier.

Soon after the Mexican War began in 1846, President James K. Polk commissioned Pierce a colonel in the U.S. Army. Only months earlier, Pierce had declined an offer to serve in Polk’s Cabinet as attorney general. A few months after the war began, Pierce was promoted to brigadier general. He served under General Winfield Scott on the expedition to Mexico City. Pierce commanded a brigade in the attack on Churubusco and suffered a leg injury when thrown from his horse. He returned to the assault the next day. When close to the enemy lines, he wrenched his injured leg, fainted from pain, and lay helpless under fire until the end of the battle. Political enemies later accused him of cowardice.

Election of 1852.

Pierce resumed his law practice in Concord after the war. He had become one of New Hampshire’s leading Democrats by the time his party’s national convention met in 1852. The delegates faced a difficult job in choosing a candidate for president who would be acceptable to all factions of the party. The four strongest candidates were Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and three former Cabinet members—James Buchanan, William L. Marcy, and Lewis Cass.

After 34 ballots, it began to appear that none of the favored candidates could win the nomination. Delegates from Virginia then nominated Pierce. The New Englander expected some Northern support, and the South trusted him because he had supported the Compromise of 1850 and endorsed strict enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law. As the balloting continued, several Buchanan delegations swung to Pierce, and he won on the 49th ballot. The convention chose Senator William R. D. King of Alabama for vice president.

The Whigs nominated General Winfield Scott for president and Secretary of the Navy William A. Graham for vice president. The Compromise of 1850 had temporarily settled the slavery problem, and no real issues appeared to separate the two parties (see Compromise of 1850 ). But the campaign disclosed that Scott really opposed slavery, causing opposition to him in the South. Pierce won a majority of the popular vote and carried many more states than did Scott.

Pierce’s administration (1853-1857)

Cabinet.

Pierce tried to promote harmony in the Democratic Party by choosing men from all factions for his Cabinet. His appointments consisted of two conservative Southerners (Guthrie and Dobbin), two conservative Northerners (Marcy and Campbell), an antislavery Northerner (McClelland), a states’ rights Southerner (Davis), and a New England Whig (Cushing). Vice President King, who had been ill for several months, died in April 1853 without ever performing the duties of his office (see King, William R. D. ).

Life in the White House

began in an atmosphere of tragedy and grief for the Pierces. They had seen their 11-year-old son Benjamin die in a railroad accident just two months before the inauguration. Mrs. Pierce collapsed from grief and did not attend her husband’s inauguration. She secluded herself in an upstairs bedroom for nearly half of his term. Washington gossips called her “the shadow in the White House.”

Mrs. Abby Kent Means, an aunt of Mrs. Pierce, served as White House hostess during Pierce’s first two years in office. Mrs. Pierce finally appeared at a White House function on Jan. 1, 1855, and thereafter attended state dinners frequently. But one visitor remarked that she remained the “very picture of melancholy.”

The Kansas-Nebraska Act.

In January 1854, Senator Douglas introduced a bill that he hoped would hasten frontier settlement. It proposed to carve two new territories, Kansas and Nebraska, out of the Indian lands in the West. The bill provided that settlers in the new territories would decide for themselves whether to permit slavery. Douglas’ bill threatened to upset the uneasy slavery truce established by the compromises of 1820 and 1850. A farsighted statesman would have seen the danger in such a law. But Pierce, acting on the advice of his party leaders, supported the bill. It became law on May 30, 1854 (see Kansas-Nebraska Act ). Both slavery and antislavery people poured into Kansas. Each group sought to control the territory. Their rivalry soon developed into armed clashes (see Kansas (“Bleeding Kansas”) ).

The Kansas-Nebraska Act created a violent realignment of political parties. The Democrats defended the existing laws on slavery. The Whigs, already weakened by sectionalism, disintegrated. This hastened the birth of the new Republican Party and the Know-Nothing Party (see Know-Nothings ; Republican Party ).

Foreign affairs.

In his inaugural address, Pierce had boldly summarized his attitude toward foreign policy by saying: “My administration will not be controlled by any timid forebodings of evil from expansion.” In 1853, he advocated annexing Hawaii. This plan fell through, partly because King Kamehameha died. The Gadsden Purchase of 1853 gave the country a southern railroad route to the Pacific Coast and settled the boundary question with Mexico (see Gadsden Purchase ). At Pierce’s insistence, the Senate ratified (approved) a trade treaty with Japan in 1854, opening Japan to American trading interests.

Acts of this kind matched the attitude of the American people, who believed in national expansion. But when three of Pierce’s diplomats claimed in 1854 that the United States had the right to seize Cuba from Spain, the public reacted against the president. See Ostend Manifesto .

Later years

Pierce’s handling of the slavery issue destroyed his political usefulness. After the inauguration of President James Buchanan, Pierce and his wife went abroad in a futile attempt to improve her health. The Pierces spent two years on the island of Madeira, visited Europe, and then returned home. Mrs. Pierce died on Dec. 2, 1863.

Pierce became a bitter critic of President Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War. Pierce charged that Lincoln could have avoided the conflict by proper leadership. During the war, Secretary of State William Seward suggested Pierce was a member of a seditious (rebellious) group known as the Knights of the Golden Circle and therefore disloyal to the Union. But the charge was proved false, and Seward later apologized for his suggestion. Pierce died on Oct. 8, 1869, and was buried in the Old North Cemetery at Concord.