Pioneer life in America. The story of the pioneers tells of the lives of thousands of ordinary people who pushed the frontier of the United States westward from the Appalachian Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. It is the tale of the many hardships and dangers and the isolation the settlers faced as they struggled to build new lives away from the civilization they had known in the East. It is also the story of a clash of peoples, as the pioneers sought to acquire lands where Indigenous (native) Americans lived.

The pioneers played an important role in the history of the United States. They contributed much to America’s knowledge about the geography, travel routes, and commercial possibilities of the West. They spread the political and social institutions and values of the new and growing nation across the continent. They also changed the look of the land as they cleared it for farms, roads, and towns. In addition, the pioneer settlement of America led to the loss of lands and traditional ways of life for many Indigenous Americans.

From about 1760 to about 1850, the pioneers moved westward in two large migrations. During the first migration, pioneers from the East Coast and from Europe advanced as far west as the Mississippi Valley. During the second migration, which began in the 1840’s, settlers from the East and Midwest migrated to the Oregon region and California. For the story of the first colonists, see Colonial life in America. For the history of settlements in the West after 1850, see Western frontier life in America. See also Westward movement in America.

Why the pioneers headed west

Pioneers moved west for a variety of reasons. Some went to the frontier in search of adventure. However, most pioneers headed west to make a better life for themselves and their children. They wanted to improve their social and economic position. Some hoped to have more say in political affairs. Many young couples and single men sought their fortune on the frontier. Land was the chief form of wealth at the time, but it generally passed from father to oldest son. Even for those who had the money to buy land, good farmland was hard to find in the East. Across the Appalachians, however, settlers could obtain a plot of fertile land for a fraction of the cost of a similar piece in the East. In time, they might decide to increase the size of their farms or sell them for a profit.

The early settlers who crossed the Appalachian Mountains included people who were from Europe or were of English, German, or Scandinavian descent. Some brought enslaved Black people with them to the frontier. However, a number of pioneers were free Black Americans who saw on the frontier a chance to start a new life. Some of them had been released from slavery by their masters or by state legislatures. Others had bought their freedom or had run away. Many Black pioneers headed for the Northwest Territory, where slavery was illegal. The Northwest Territory, originally known as the Old Northwest, covered the area that is now Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and part of Minnesota.

However, some communities and territories passed laws that discriminated against Black settlers. For example, the Indiana Territory passed a law in 1803 that prohibited Black people from testifying in any trial involving white people.

Moving westward

Thousands of settlers crossed the Appalachian Mountains during the late 1700’s and the early 1800’s. These pioneers established frontier settlements in Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and other lands as far west as the Mississippi Valley. This section and the sections A pioneer settlement and Pioneers and Indigenous peoples discuss this frontier. For the story of America’s second big migration, to Oregon and California, see the section Crossing the Plains.

Before the arrival of the pioneers.

When the pioneers arrived in the region between the Appalachians and the Mississippi, they came upon a land of great natural beauty. Making up part of an area commonly called the Eastern Woodlands, the region had thick forests, sparkling lakes and streams, and plentiful fish and game. Near the Mississippi River, the forest gave way to rolling prairie. The rich soil and adequate rainfall of the region made it well suited for farming.

The land between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River had been home to a number of Indigenous cultures long before the pioneers arrived. The ancestors of some of these groups had come to the area as early as 10,000 B.C. The members of the powerful Iroquois League as well as such tribes as the Fox, Illinois, Sauk, and Shawnee inhabited the northern part of the region. The Cherokee and Chickasaw were among the tribes who lived farther south. The Indigenous peoples of the Eastern Woodlands and nearby areas were farmers and hunters. They built permanent houses made of poles, bark, and mud. Many Indigenous Americans lived in communities of several hundred people.

Stages of settlement.

People of European descent came to the region between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River in several—often overlapping—stages. The first to visit the region were missionaries, fur traders, and explorers from England, France, and Spain. Soon, military outposts were established in the area. Later, American traders, explorers, and troops came to the frontier. They were followed by cattle ranchers, who grazed their cattle on the open prairies of the region. Finally, the pioneer farmers arrived on the frontier.

The first pioneer farmers made clearings for small farms. After several years, many of these settlers sought new opportunities on cheaper lands farther west. Their places were taken by pioneers who developed larger farms and built permanent communities. Soon the growing settlements attracted blacksmiths and other craftworkers, merchants, millers, doctors, and teachers.

Crossing the Appalachians.

The first pioneers crossed the Appalachian Mountains along steep, narrow trails originally opened by Indigenous people and later used by white explorers and traders. In time, the trails became wide enough for wagons. Boats carried pioneers on the rivers.

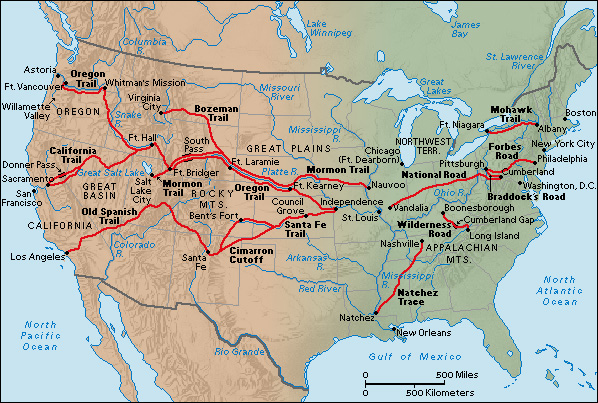

The pioneers followed several main routes on their way west. One route went through Cumberland Gap, a natural pass in the Appalachian Mountains near the meeting point of Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia. In 1775, a band of woodsmen led by Daniel Boone cut the Wilderness Road through the gap. Another route followed river valleys through Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh. There, many pioneers boarded river craft and floated down the Ohio.

In 1811, work began on a road that would eventually run between Cumberland, Maryland, and Vandalia, Illinois. It became known as the National Road or the Cumberland Road. Many pioneers from New England traveled west on the Mohawk Trail across New York. Then they followed the southern shores of the Great Lakes. The Erie Canal became an important water route after its completion in 1825.

How the pioneers traveled.

Most pioneer families joined several others who were making the same journey west. Some pioneers set off on foot, carrying only a rifle, ax, and a few supplies. However, most pioneer families had one or two pack animals and a wagon or a cart. Some took along a cow to provide milk and to carry a load of goods. Some had chickens, hogs, and sheep. Dogs herded sheep and helped hunt game.

The settlers could not take all their belongings with them when they traveled to the frontier. The two items that were essential for survival were a rifle and an ax. The rifle was needed for shooting game and for protection. The ax was used to cut logs for a raft or a shelter or to clear land for a farm.

Any bulky tool or household utensil that could be made on the frontier was left behind. Most pioneers took along a knife, an axlike tool known as an adz, a tool called an auger for boring holes, a hammer, a saw, a hoe, and a plowshare. Household goods consisted of a few pots and pans, an iron kettle, and perhaps a spinning wheel. Families made room for essential clothing, blankets, and such prized possessions as a clock and family Bible. They also brought along seed for planting their first crops on the frontier.

The pioneers hunted and fished for food on their journey. They also carried some corn meal, salt pork, and dried beef. Johnnycake, a kind of corn bread, was a favorite food because it did not spoil on the long trip.

The pioneers could travel only a short distance each day, and most trips across the mountains took several weeks. Later, after roads had been built, the Conestoga wagon became the favorite vehicle for travel. Conestogas had broad-rimmed wheels, sloping sides that were higher than the middle, and a rounded, white canvas roof. They were pulled by horses, oxen, or mules. The Conestoga was named for the Pennsylvania valley where it was first built. See Conestoga wagon.

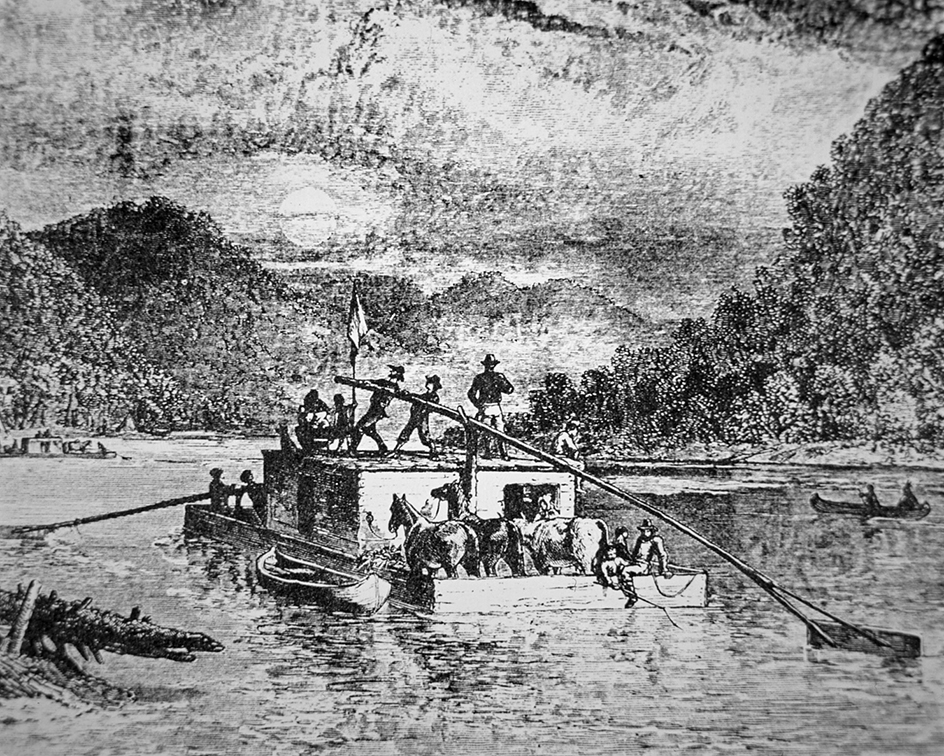

A barge known as a flatboat was commonly used for river traffic. Early flatboats could carry one family, a wagon, and several horses or other livestock. Later flatboats were large enough to transport several families with all their supplies and livestock. These boats had a boxlike house in their center. The house became a floating fort in case of attack by Indigenous raiders or river pirates. Some of the pioneers ended their journey by settling near the river. They took apart the house and flatboat and used the lumber to build shelters ashore. Other types of river craft included simple rafts; canoes; narrow barges called keelboats; and, after 1811, steamboats.

How the pioneers obtained land

depended on where and when they settled. During the early settlement of Kentucky and Tennessee, for example, pioneers simply located and staked out the lands they wanted. Soon land companies and wealthy individuals called land speculators began to claim huge pieces of land. These groups and individuals bought land or received ownership from colonial governments or by royal decree. They divided the land into smaller homesites and then resold it to the settlers for a profit.

Land speculators sometimes acquired land from the Indigenous groups in the region. In many cases, however, tribes believed they were granting only the right to use the land, not the right to possess it. Furthermore, Indigenous lands belonged to the tribe as a whole. A group of individuals, even if they were chiefs, did not have the right to sell the lands. These misunderstandings were among the causes of conflict between settlers and tribe members.

A law called the Ordinance of 1785 provided for the division and sale of land north of the Ohio River between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. It stated that land there could not be settled until after the federal government had surveyed it. After the land was surveyed, it was to be sold at government auction to the highest bidder. Speculators and land companies bought most of the land and resold it in smaller plots to settlers.

Many pioneers settled on public land before it had been surveyed. These settlers, who did not have title to the land, were known as squatters. In 1841, Congress passed a law that enabled squatters to buy their land under rights of ownership called squatter’s rights.

Establishing a homestead.

When a pioneer family arrived where they intended to settle, they could not spare enough time to build a permanent house right away. Instead, they put up a temporary shelter. A framework of poles covered with branches and mud formed the roof and three sides of the shelter. The fourth side was open and faced a fire that burned day and night. During the day, the fire was used to cook food. At night, it warmed the shelter and kept away wild animals.

Most pioneers arrived at a settlement in spring, the planting season. A spring arrival gave them time to clear the land and grow crops for the next winter. Pioneers used axes to cut away the brush, chop down trees, and trim logs. Neighbors lent a hand removing rocks and stumps. Every member of the family helped with the work of starting life on the frontier.

A pioneer settlement

The log cabin

was the typical pioneer home in Kentucky, Tennessee, and many other wooded regions. The pioneers cut trees into logs and then chopped notches close to the ends. The notches held the logs to each other when they were fitted together to form the sides of the cabin.

Most log cabins were about 16 feet (4.9 meters) wide and 20 feet (6 meters) long. The sides of a cabin were about 7 feet (2.1 meters) high. The logs were too heavy for one person to lift, and so neighbors gathered to help one another. The job was called a house-raising. After the logs were in place, the spaces between them were plugged with moss, clay, or mud. Filling the spaces was called chinking.

Roofing began after the cabin walls had been completed. First the pioneers fitted logs together on top of the walls to form the frame of the roof. Then they fastened clapboards (thin boards) to the frame. They overlapped the clapboards so that rain would run off. Few of the early pioneers had building nails. They used wooden pins to hold the parts of the roof together.

The ground served as the cabin floor until the family found time to make a wooden floor. Pioneers split logs lengthwise into long slabs called puncheons. Then they pushed them into the earth, split side up, and wedged them together. A puncheon floor was smoother and warmer than the ground, and it improved the looks of the cabin.

A fireplace stood at one end of the cabin. Most fireplaces had a log chimney that was lined with a thick layer of clay or mud to keep it from catching fire. Some had stone chimneys. The family kept a fire burning in the fireplace most of the time for cooking and to provide warmth and some light.

Some frontier cabins had no windows, and others had only small ones. Pioneers covered windows with shutters or with greased paper, which let in light. Glass later replaced these window coverings when shopkeepers brought it from the East.

The cabin door was made of thick pieces of wood fastened to crosspieces. The door swung on wooden hinges. A deerskin string was tied to the latch and hung outside. When someone pulled the latchstring, it drew up the latch and the door opened. At night, the latchstring hung inside, and the family put strong bars across the door to hold it shut.

Furniture and household utensils.

A family started life on the frontier with a few pieces of handmade furniture and some household utensils. After getting settled, the pioneers bought other items from a peddler or a frontier store. Every growing settlement had a blacksmith, a cabinetmaker, and other craftworkers.

The family’s table was made of several split log slabs and sturdy legs. Benches and stools were made of smaller slabs. A pole stuck into a wall formed the outside rail of the bedstead. A notched post held up the free end of the pole. Cross poles laid from the pole to a side wall held a mattress stuffed with dried moss, grass, or straw. Quilts, blankets, or animal skins served as bedcovers. Many pioneers had no beds. They rolled up in bear or buffalo skins and slept on the floor. Some cabins had a loft where the children slept.

Pioneers made many of their household utensils. They carved wooden spoons, ladles, bowls, and platters. They also whittled long pegs that were driven into cabin walls to hold the family’s clothing. Deer antlers, hung over the door or fireplace, made a good rack for the pioneer’s rifle, bullet pouch, and powder horn. Gourds served as cups and containers. Candles provided light.

Food.

Corn and meat were the basic foods of a pioneer family. The family ate corn in some form at almost every meal. The pioneers grew corn as their chief crop for several reasons. It thrived even in uncultivated soil, kept well in any season, and could be used in many ways. The pioneers ground corn into meal. They used the meal to make mush or various kinds of corn bread—ashcake, hoecake, johnnycake, or corn pone. They also made a dish called hominy by softening whole, dried corn in sodium hydroxide (lye) or water to remove the hull. For a special treat, families roasted ears of corn. The pioneers also used corn as feed for their animals.

The pioneers raised cattle, hogs, sheep, and chickens. They also hunted wild fowl and other game for much of their meat supply. Many meals consisted of wild duck, pigeon, or turkey, or bear, buffalo, deer, opossum, rabbit, or squirrel. Fish were abundant in lakes and streams.

The pioneers had no refrigeration, but they knew how to keep meat from spoiling. They cut some kinds of meat into strips that they dried in the sun or smoked over a fire. Some meat, especially pork, kept well after being salted or soaked in brine (salty water).

Salt was in great demand on the frontier for preserving and seasoning food. It brought a high price when traders from the East sold it by the barrel. Rather than pay the high price, some settlers banded together once a year and traveled to a salt lick. Salt formed naturally on the ground at some salt licks. Salt springs bubbled up out of the ground at others. At a salt lick, settlers could gather salt or boil their meat in the salty water. Wild animals also came to licks for the salt, and so pioneers often found good hunting there.

The pioneers grew vegetables and herbs for their own use and occasionally to trade with a local shopkeeper for other goods. Most of the vegetables planted by the settlers—beans, cabbages, potatoes, pumpkins, squash, and turnips—could be cooked into hearty meals. To flavor dishes, pioneers used garlic and such herbs as parsley, rosemary, sage, and thyme.

Families that owned a cow often had milk with their meals. Coffee and tea were too expensive for most frontier families except on rare occasions. Whiskey made from corn was a common drink. The pioneers sometimes mixed corn whiskey with water, added some sweetener, and served it to the entire family. Common sweeteners included honey, molasses, and maple sugar or maple syrup.

Clothing.

For their first year or two on the frontier, most pioneers wore the clothes they had brought with them. After this clothing wore out, they made their own. Fabrics were expensive, and making clothes was a long and difficult process. Pioneer women generally took responsibility for making clothes. They spun linen yarn from flax and wool yarn from the fleece of sheep. They then wove the yarn into cloth, which they used in making shirts, trousers, dresses, and shawls.

Many frontiersmen wore a hunting shirt made of deerskin or linsey-woolsey, a coarse homemade cloth of linen and wool. The shirt fitted loosely and hung to the thighs. It had no buttons and was held in place at the waist by a belt. Instead of a collar, the shirt had a cape, sometimes trimmed with fringe. Frontiersmen wore deerskin trousers. Deerskin became cold and stiff when wet and felt uncomfortable next to the skin. A man in deerskin usually wore underclothes of linsey-woolsey.

Linsey-woolsey was also commonly used to make clothing for women and children. Most pioneer women wore a petticoat and a dress that resembled a smock. The petticoat was worn as a skirt, rather than as an undergarment. In cold weather, women wore a shawl of wool or linsey-woolsey. Children wore the same kind of clothing as their parents.

The pioneers wore the shoes that they had brought with them for as long as they could. They went barefoot whenever possible to extend the life of their shoes. When their shoes finally wore out, the pioneers bought new ones from a local merchant or bartered furs or other goods for shoes. In the early stages of frontier life, some settlers made moccasins or shoepacks of hide. Shoepacks resembled moccasins, but they covered the ankles and had sturdy soles. For warmth and comfort, the pioneers stuffed their moccasins or shoepacks with deer hair or leaves.

In summer, the women and girls wore sunbonnets large enough to shield the face and neck. In winter, they wore woolen bonnets or covered their heads with shawls. Men and boys wore coonskin caps or fur hats in cold weather. In summer, they put on hats made of loosely woven straw or cornhusks.

Tools.

Pioneers started farming with the hoe, plowshare, and other tools that they brought with them. The cabin soon became a workshop as well as a home. The pioneers made most of their own farm tools, including harrows and rakes, which were used to break plowed earth into finer pieces and smooth the soil.

A number of tools and techniques were involved in making corn meal. First, the pioneers pulled off the cornhusks. In most cases, they then shelled the corn—that is, they removed the kernels from the ear. Some pioneers separated the kernels from the cob by hand. Others used a homemade threshing tool called a flail or another implement.

The pioneers made several kinds of mills to grind the kernels into meal. Some made a hand mill called a quern. This mill consisted of two large, flat stones, one on top of the other. The top stone had a wooden handle attached to it and a hole through the center. Kernels were placed in the hole. When the handle was turned, the corn was ground into meal between the stones. Another type of mill consisted of a heavy log and a hollowed tree stump. Corn was put into the hollow and pounded into meal with the log. Some pioneers simply grated the corn into a coarse meal. They made a grater by punching holes in a sheet of iron and fastening it to a block of wood. A husked ear of corn was rubbed against the sharp, raised edges of the holes in the metal.

The pioneers usually molded their own bullets from lumps of lead sold by the settlement storekeeper, who also sold gunpowder. They obtained iron tools from a blacksmith. Pioneers often used corn or corn meal instead of money to buy supplies. If a settlement had no store, a few settlers traveled together to the nearest town or trading post to buy what they needed.

Health.

One of the greatest dangers to the pioneers was disease. Epidemics on the frontier killed large numbers of people, especially children and older people. The most feared disease was smallpox. Many communities suffered outbreaks of cholera, malaria, and yellow fever. Such childhood diseases as whooping cough, diphtheria, and scarlet fever were common.

The settlers also suffered from colds and other minor illnesses. Nearly everyone was affected at one time or another by a malarial fever called ague. Accidents resulting in cuts, bruises, sprains, and broken bones occurred frequently. Childbirth was dangerous. Pioneer women bore children without the benefit of proper medical care. Many women died in childbirth, and many children died at birth or as babies.

There were few doctors on the frontier. The main responsibility for caring for the sick fell upon the pioneer women. They relied on a combination of home remedies and folk cures to treat illnesses. For example, one cure for colds and sore throats involved tying a piece of fat meat with pepper around the neck of the sufferer. Wearing a bag of asafetida, an herb that smells like garlic, around the neck was said to keep a person healthy. Some diseases were treated by bloodletting—that is, having some blood removed from patients. Bloodletting, also called bleeding, was believed to remove “bad blood” and fever from the sick. This procedure was typically carried out by a doctor, apothecary (pharmacist), or barber.

Indigenous healing practices also became popular among the pioneers. Such treatments often involved the use of plants, herbs, and the bark of trees. For instance, a brew of boneset tea was used to treat colds. Chewing prickly-ash bark eased toothaches. Sassafras and goldenseal helped relieve stomach ailments.

Education.

At first, education on the frontier was informal. Parents who could read taught children some lessons from the Bible and other books that they brought with them from the East. Soon, frontier communities set up formal schools. Most schools had only one room and were built by the settlers. The pupils sat at long wooden benches or crude desks.

Teachers were scarce. Many did not stay long in a particular area, and others left the profession after only a few years. In many cases, a teacher was boarded around in payment for services. The teacher lived for a few months with one family and then with another, receiving food and lodging. Some communities paid their teacher a small salary. Most teachers had little, if any, formal training.

A settlement school had few books and no chalkboards, charts, or maps. The children learned by repeating lessons read by the teacher. The teacher taught them reading, writing, and arithmetic. Famous textbooks included the readers of William H. McGuffey and the spelling books of Noah Webster. Spelling bees were both a part of the school curriculum and a popular form of recreation. Adults and children alike competed for the honor of being the best speller in the community.

Students wrote on wooden boards and used pieces of charcoal as pencils. Some had pens made of goose quills and ink made from bark or berries. Slates came into use about 1820. Most children attended school only during the winter. At other times, they were needed at home to help with the farm and household tasks.

Religion

was an important part of pioneer life. Most settlers were Christians, and almost every large pioneer settlement had a church. In small settlements, services were held in family homes. Parents taught prayers and hymns to their children and tried to keep Sunday as a day of rest and worship.

A traveling preacher visited many settlements regularly. He conducted church services and funerals and performed marriages and baptisms. The preacher was called a circuit rider because he rode horseback from one settlement to another on a route known as a circuit.

Sometimes a preacher organized a camp meeting. This special outdoor religious service lasted several days and nights and attracted families from many settlements. People brought food and other supplies and camped in a large clearing where the meeting was held. Members of many religious groups attended camp meetings, which often featured several preachers. Methodists typically made up the largest group, but such denominations as Baptists and Presbyterians also took part.

Camp meetings and other religious gatherings served an important social function in addition to a religious role. They were good places to catch up on news or simply gossip. They also enabled single men and women to make friendships that could lead to courtship and marriage.

Government.

Early frontier settlements had no formal governmental bodies or law enforcement officials. The community as a whole usually made decisions, settled disputes, and punished troublemakers. Sometimes a special commission consisting of several prominent members of the community was set up to resolve conflicts between individuals.

In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance. This law established rules for formal government in the Old Northwest, which then became known as the Northwest Territory. This territory became a model for all territories that later entered the Union as states. The ordinance declared that at first a territorial government would consist of a governor, a secretary, and three judges appointed by Congress. After its adult male population reached 5,000, a territory could elect a legislature and send a nonvoting delegate to Congress. After the population reached 60,000, a territory could write a state constitution and apply for statehood.

Generally, the first action a territorial government took was to organize a local militia. The militia served as a territory’s military force. It also supervised elections and set and collected taxes. In time, officials of the county court system took over many functions from the militia. These officials included a surveyor, a treasurer, a coroner, a sheriff, a justice of the peace, and a county clerk. They kept law and order, issued licenses, and set fees for local businesses. They also assessed and collected taxes.

Social activities.

The pioneers brightened life on the frontier with parties and other get-togethers. They mixed work with fun and sports whenever possible. In autumn, they held cornhusking contests and nut-gathering parties. In spring, they assembled in maple groves to make sugar and syrup. The women often got together for quilting parties. The quilts were much in demand as bedcovers.

The settlers always enjoyed a house-raising. The men stopped working on the house now and then to run races or to hold wrestling bouts or shooting contests. After the job was finished, everyone celebrated with a lively feast. The women prepared plenty of food, and after eating, the settlers sat around telling stories. As a rule, someone brought along a fiddle, and dancing and singing went on until late in the night.

A wedding was a special time of fun and celebration. The pioneers liked to play tricks on a couple about to be married. Sometimes the women “kidnapped” the bride while the men rode off with the groom. Of course, both managed to escape in time to be married. During the couple’s wedding night, some guests, usually young men and boys, gathered outside the newlyweds’ home. There, the assembled group shouted, banged on pans, and otherwise created great noise in a tradition called a charivari << `shihv` uh REE >>.

Pioneers and Indigenous peoples

Peace and war.

During the colonial period, the British Proclamation of 1763 forbade white settlement west of an imaginary line drawn through the Appalachian Mountains. The proclamation was designed to prevent pioneers from moving onto western lands, which Indigenous groups were prepared to defend. But many colonists ignored the proclamation, which was not strictly enforced, and settled west of the Appalachians anyway. Treaties negotiated with Indigenous leaders in 1768 shifted the proclamation line westward and opened the way for settlement of what are now West Virginia and southwestern Pennsylvania. Some pioneers went as far west as what are now eastern Kentucky and Tennessee.

Beginning with President George Washington, the official policy of the United States toward Indigenous peoples was generally one of peace through negotiation, trade, and treaties. According to laws passed during the 1790’s, only the U.S. government could acquire land from Indigenous peoples. Trade between white traders and Indigenous groups was to be regulated by the government to curb unfair practices. Laws and treaties recognized and guaranteed Indigenous rights to certain lands.

However, neither the U.S. government nor the Indigenous peoples of North America foresaw the crush of settlers that would be moving west in the early 1800’s. The pressure of white settlement was so great that orderly relations between the pioneers and Indigenous people were difficult to maintain. Many land speculators and settlers ignored the rights that Indigenous tribes had been guaranteed under treaties. Some groups of white people—including some militias—conducted armed invasions into lands that had been reserved for Indigenous people. Some Indigenous people, in turn, raided pioneer settlements.

There were several periods of major fighting between Indigenous tribes and U.S. troops in the region between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River. A series of conflicts between the Army and the Indigenous groups north of the Ohio River, in the Northwest Territory, occurred during the early 1790’s. It ended when the Army defeated a confederacy of Ohio Valley and other Great Lakes region tribes in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794.

A second major period of hostility began in the early 1800’s. At that time, a Shawnee leader named Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, known as the Shawnee Prophet, organized an alliance of tribes to try to stop westward expansion by white settlers. Tecumseh objected to the pioneer settlement of Indigenous lands, and his forces raided many frontier communities. Many tribes in Tecumseh’s alliance joined forces with the British against the United States during the War of 1812. Tecumseh was killed in Canada at the Battle of the Thames in 1813. The uprising ended shortly after his death. See Indian wars.

The early treaties between the United States and the Indigenous peoples guaranteed that Indigenous groups could remain on certain lands. However, as more settlers moved into the area between the Appalachians and the Mississippi River, many tribes were pushed off their lands. In 1834, the U.S. government created the Indian Territory, a large reservation west of the Mississippi. The reservation spread across an area that covers what are now Oklahoma and parts of Kansas and Nebraska. By 1840, more than 70,000 Indigenous people from east of the Mississippi River had been forced to move to the Indian Territory. Thousands of Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and other Indigenous people died on the journey westward. The Cherokee came to refer to their migration as the Trail of Tears. The name was later applied to the forced removal of other tribes as well.

Defending a settlement.

Most settlers were never attacked by Indigenous raiders, but they lived in constant fear of raids nevertheless. Everyone kept careful watch for raiders and warned their nearest neighbors at the first sign of danger. Messengers spread the alarm throughout the settlement.

A fort called a stockade or station was the main defense of a frontier settlement. A typical stockade was rectangular, with walls of sharply pointed logs at least 10 feet (3 meters) high. Small sheds or cabins provided living quarters in the stockade. In at least one of the corners of the fort stood a blockhouse, a two-story tower built of thick timber. Some stockades had a blockhouse in each corner. A blockhouse held at least 25 people. Members of the local militia stood guard at firing posts in blockhouses. Firing posts were narrow slits in a wall, just wide enough to shoot through.

The stockade also sheltered new arrivals at a settlement. Newcomers headed for the stockade, where they learned what to do in case of an alarm. Most new arrivals at an established settlement stayed in the stockade until they began settling on their land.

Crossing the Plains

By the 1830’s, the first big westward migration had pushed the frontier to the Mississippi Valley. Pioneers were rapidly settling the area just west of the Mississippi River that became the states of Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa. Explorers, missionaries, traders, and fur trappers had gone even farther west and southwest. They told of great forests and fertile valleys in the Oregon region and other lands west of the Rocky Mountains.

The stories of the trailblazers made exciting news for many Midwestern settlers. In the 1840’s, some Midwesterners chose to migrate to Oregon in search of more opportunities. So did hundreds of families from the East who had just arrived in the Midwest and were seeking places to settle. The Mormons, fleeing persecution in Illinois because of their religious beliefs, also decided to head westward. In 1847, they began to settle in the valley of the Great Salt Lake in what is now Utah. Some Black people in the Midwest hoped to escape discrimination by moving to the West, but they often faced prejudice there as well. After gold was discovered in California in 1848, thousands of fortune seekers joined the westward migration. See Mormons; Gold rush.

Routes to the West.

The settlers encountered several natural obstacles on their way to the fertile valleys of Oregon or the gold fields of California. First, they had to cross the Great Plains, a vast grassland that runs between Canada in the north and Texas and New Mexico in the south. The rugged Rocky Mountains rose west of the Great Plains, and beyond the mountains lay a stretch of desertlike terrain known as the Great Basin. The weather was also a problem. Heavy rains might wash out a river crossing. A spell of dry weather could lead to a shortage of water to drink, less grass for the cattle to eat along the way, and more dust to choke the travelers.

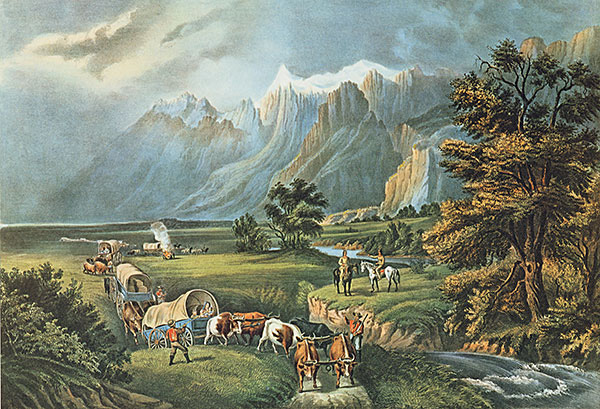

From 1840 to 1860, more than 300,000 people crossed the plains and mountains of the West. Most were bound for Oregon or California. For the long trip, as many as 200 wagons at a time joined together to form a caravan called a wagon train. However, trains of 30 or fewer wagons were more common. Most settlers started from Independence, Missouri, and followed a route called the Oregon Trail. Those bound for Oregon took this trail northwest to the Columbia River and from there to the Willamette Valley.

Settlers bound for California split off from the Oregon Trail near Fort Hall, in what is now Idaho. They followed any of several trails southwest to Sacramento, California. Some settlers took the Santa Fe Trail from Independence to California. This route took settlers to Santa Fe, in present-day New Mexico. From there, pioneers followed the Old Spanish Trail to Los Angeles.

From 1835 to 1855, more than 10,000 people died while traveling on the Oregon Trail. The chief causes of death were firearms accidents and such diseases as cholera and smallpox. Only 4 percent of the deaths among pioneers on the Oregon Trail resulted from attacks by Indigenous peoples.

The wagon train.

A family going from Independence to Oregon or California in the 1840’s had to plan on a journey of four to six months. They had to be sure they brought enough supplies for the trip because there were few places where they could buy goods along the way. Often travelers traded such items as food, clothing, and firearms among themselves or purchased them from one another. Several guidebooks provided information on the route the travelers were to take as well as tips on what provisions were needed for the journey.

During most of the trip, the family lived in a canvas-covered wagon pulled by several teams of oxen or mules. The wagon resembled the Conestoga but was smaller and sleeker. It was called a prairie schooner because, from a distance, its white top looked like the sails of a ship. Many families painted pictures and slogans on the wagon’s canvas covering for decoration. Such markings also made it easier for friends to find each other on the crowded trail.

Some single men traveled on horseback with wagon trains. They herded the livestock or rode alongside the wagons, helping the drivers stay on the trail. A wagon train had a large number of livestock. Some trains included more than 2,000 cattle and up to 10,000 sheep.

Each wagon train elected a leader, called a captain or wagon master. All wagon trains were guided by a scout who knew the route and the best places to camp.

Life on the trail.

Almost all westward journeys started in the spring. A spring departure gave the pioneers time to get through the western mountains before snow blocked the passes. It also helped ensure adequate grass for the livestock. Most wagon trains could travel about 12 to 20 miles (19 to 32 kilometers) a day. They stopped for a day or two at such Wyoming outposts as Fort Laramie or Fort Bridger to repair equipment and buy supplies. If the oxen hauling the wagons became exhausted, they were shot or simply left to die where they fell. Some were eaten for their meat. In most cases, they were replaced by other animals that had been herded behind the wagon train.

A day on the trail began shortly before dawn. After the travelers rounded up their livestock, hitched their teams to the wagons, and ate breakfast, the train started out. About midday, it stopped for a break known as nooning. This break gave both the pioneers and the livestock a chance to eat and to rest. Afterward, the train pressed on to the place where the travelers would camp for the night. When the train arrived at the campsite, the wagons formed a circle for protection against wild animals and possible attacks by Indigenous raiders. In the evening before bed, the pioneers gathered around campfires in the circle to eat and chat. Sometimes, if someone had a fiddle, they sang and danced. Usually, however, they were so exhausted by their day on the trail that they went to sleep as early as possible.

Indigenous peoples on the Plains.

The Oregon Trail crossed lands that the U.S. government had guaranteed to Indigenous groups. The route ran through the hunting grounds of a number of Indigenous peoples. Fighting occasionally broke out between the pioneers and Indigenous people, who opposed this intrusion on their territory. However, most wagon trains had a peaceful journey along the trail. Some tribes guided the early pioneers or helped them at difficult river crossings. Many Indigenous people supplied some wagon trains with vegetables and buffalo meat in exchange for tobacco, whiskey, or pieces of iron. During the late 1850’s and early 1860’s, farmers and cattle ranchers began to settle on the Great Plains. At that time, fighting became more common as tribes sought to defend their territory.