Printing is one of our most important means of mass communication. It is the process by which words and images are reproduced on paper and on such other materials metal, glass, and fabrics. Printing provides books, tests, and many other study materials for our educational system. Business depends on printing for a wide variety of items, including stationery, order forms, and shipping labels. Printed advertising, from magazine and newspaper advertisements to coupons and billboards, is a popular way to sell goods and services.

Printing is a major industry in many countries. In addition to books, newspapers, magazines, and catalogs, thousands of other items are printed every day. These items include candy bar wrappers, calendars, ruled writing tablets, T-shirts, post cards, playing cards, and reproductions of works of art. Special machines can even print directly on cans or on glass or plastic bottles.

Many people confuse the printing industry with the publishing industry. Publishing is the process of assembling written information and graphics (illustrations), and coordinating the production, distribution, and sale of the resulting product. Some publishers own their own printing equipment and do the actual printing of their products, as most daily newspapers do. Most publishers, however, do not own printing equipment. Instead, they contract with a commercial printer to have their books, magazines, or papers printed.

Printing as we know it began in Europe less than 600 years ago. Printing with movable type had existed in East Asia since at least the 700’s, but the invention had not spread to Europe. Everything people read had to be copied by hand or printed from wood blocks carved by hand. Then about 1440, the German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg and his associates developed movable type. Gutenberg made separate pieces of metal type for each character to be printed. With movable type, a printer could quickly make many copies of a book. The same pieces of type could be used again and again, to print many different books.

Printing soon became the first means of mass communication. It put more knowledge in the hands of more people faster and more cheaply than ever before. As a result, reading and writing spread widely and rapidly.

Separate World Book articles, such as Bookbinding and Photocomposition , provide details on various steps in the printing process. Other articles, including Engraving , Etching , Intaglio , and Screen printing , give information on printmaking in the fine arts.

Preparing material for printing

All printing processes follow certain basic steps in preparing text and illustrations for printing. These steps include (1) typesetting, (2) preparing illustrations for reproduction, and (3) page makeup.

Typesetting

is the assembly of individual letters and numbers to create the text portion of the printed piece. In the past, skilled workers called compositors took individual pieces of carved and cast metal type and manually arranged them, letter by letter, to form lines and pages of text. Mistakes were common, and a sample copy of a complete page, called a proof, was checked for errors before proceeding with other steps in the printing process. This checking of sample pages became known as proofing or proofreading, and it is still a major part of the printing process. See Proofreading .

Three important typesetting processes are (1) electronic imagesetting, (2) hot-metal typesetting, and (3) phototypesetting. Electronic imagesetting is the main typesetting process used today. It can produce both text and graphics. Hot-metal typesetting and phototypesetting produce text only.

Electronic imagesetting

uses computers and computer printers to produce many kinds of printed materials, including catalogs, advertisements, and legal documents. Programs for these computers enable users to perform such tasks as word processing, type selection, reproduction of graphics, and page makeup, which involves the positioning of both text and graphics on a page. Some programs enable users to stretch letters, condense them, and change them in a number of other ways. A type face, also called a font, can be viewed on the computer screen and changed with the push of a key or the click of a button on a device called a mouse. The computer can also justify the text—that is, it can adjust the spacing between words so that all full lines are the same length.

After a page has been designed and the text typed in, the information is converted to a digital (numeric) file. A digital file can be used in several ways. It can be transmitted to a desktop printer to produce a proof. The use of desktop machines to typeset and print newsletters, books, newspapers, and magazines is often called desktop publishing. A digital file can also be stored on a computer disk for later use. Or it can be sent through a computer network via a device called a modem.

In a process called photocomposition, digital files may be output directly to laser platesetters. These machines produce printing plates, flat pieces of metal or plastic bearing an image of the material to be printed. Or, the digital file can be sent to a photoimagesetter, a machine that creates light-sensitive paper or film of complete pages of text and graphics. The paper or film is then used to produce printing plates. See Photocomposition .

Hot-metal typesetting

was the dominant form of typesetting from the late 1800’s until the mid-1900’s It is still used today for limited printing of greeting cards, diplomas, and specialty items. The process uses molten metal and molds of letters, numbers, and other characters to produce type. A worker sits at a keyboard on a typesetting machine and enters the text to be typeset. The machine retrieves the necessary molds and spaces and arranges them according to the commands.

There are two kinds of hot-metal typesetting machines, the Monotype and the linecaster. The Monotype molds type character by character. When the typesetter strikes keys on the keyboard, a series of holes are punched into a paper tape. The holes form a code that tells the machine which characters of type are required. A linecaster places a character mold in position for each key struck. When a line is completed, the machine uses hot metal to cast the entire line at once. The most popular type of linecaster is the Linotype.

Phototypesetting

produces images of letters and other characters on light-sensitive film or paper. It is also called cold-type composition. Phototypesetting was the dominant typesetting process from the 1950’s to the 1980’s, but it is rarely used today.

Preparing illustrations for reproduction.

Printers deal with two main types of graphics, line reproductions and halftone reproductions. Most printing operations use electronic scanners, which record an image with light sensors, or digital cameras to produce digital files of both kinds of graphics. But photographic techniques can also be used to generate either type of image.

Line reproductions are used for line art—illustrations that consist of solid areas or solid lines. Such graphics include pen-and-ink drawings, maps, diagrams, and other illustrations without color or shading.

Halftone reproductions are required when the illustrations have a range of tones or shades from dark to light. Such material, called continuous-tone copy, includes paintings and photographs. A printing press can print only solid colors, not continuous tones. The illusion of shading, however, can be created by printing a pattern of tiny dots. To the viewer’s eye, the dots blend and seem to duplicate the shading of the original art.

Most halftones are produced electronically. First, illustrations are converted to digital code. This may be done by photographing subjects with a digital camera, or by converting prints or slides to digital images using a scanner. A computer is used to determine the organization of the dots for the halftones. In a technique called AM screening, the centers of the dots are equally spaced, but the dots vary in size. In FM screening, the dots are all the same size, but the spacing between them varies. To learn how color illustrations are printed, see the Printing in color section of this article.

Some reproductions are created photographically. Special cameras shoot images onto high-contrast film, producing images of the exact size needed for the printed reproduction. For line copy, a simple negative is made. Halftone images can be produced photographically by shooting an illustration through a piece of film called a halftone screen. This screen is mounted between the camera lens and the photographic film. It carries a pattern of transparent squares on a black background. As in AM screening, the squares are equally spaced but vary in size. Light reflected from the copy passes through the squares and forms an image on the negative.

Page makeup,

also called image assembly, involves arranging type and illustrations to form pages. Pages can be assembled by hand, but most designers use computers. Special computer programs enable designers to integrate digital files of text and graphics to assemble pages. On a computer monitor, a designer can see exactly where the text and graphics—represented by boxes called windows or frames—will appear on a page. The designer can quickly adjust the positions of the windows. When the page is printed, the text and graphics appear where the designer positioned the windows. The page can be printed using a computer printer. The pages can also be output directly to a printing plate, or the image can be transferred onto light-sensitive paper or film that will then be transferred to a printing plate. For certain applications, the output is produced with the graphics windows taking the place of the illustrations.

Platemaking.

Once the individual pages are made up, they are imposed—that is, put into position for the printing plate. They can be imposed directly from a computer to a printing plate or to paper or film, or the pages can be positioned by hand.

When laying pages out by hand, a specialist called a stripper positions film negatives of pages onto a sheet of plastic or special paper in a process called stripping. The stripper places dark boxes or cuts out windows where line and halftone negatives will be inserted. If the pages have been laid out on a computer and transferred onto paper or film, the illustrations are usually already in position. When everything is in place, the stripper cuts away the paper or plastic from the image areas, allowing the image to transfer onto a light-sensitive printing plate. The plate picks up these images for reproduction on the printing press.

Methods of printing

Most commercial printing today is done by one of four processes: (1) offset lithography, a type of planographic printing; (2) relief printing; (3) recess printing, also called gravure printing; (4) and digital printing. Each of these processes uses a different kind of printing surface to carry the images to be printed. In offset lithography, the most widely used process, the printing surface and the nonprinting surface are on the same level. In relief printing, which includes letterpress and flexographic processes, the printing surface is raised. In recess printing, which includes engraved printing, the printing surface is below the nonprinting surface. Digital printing uses an electrically charged drum and a dry or liquid ink called toner, or inkjets that drop or spray ink on the printing surface without even touching it.

Printing presses print on sheets or rolls of material called a substrate. Usually the substrate is paper, but other commonly used substrates include plastics, foils, and cardboard for packaging. Presses that print on sheets are called sheet-fed presses. Those that print on rolls are called web-fed presses or web presses. A roll of substrate is called a web.

Offset lithography

is based on the fact that grease and water do not mix. The process is also more simply called offset or lithography. Alois Senefelder, a German printer, discovered the principle of lithography in 1798. He drew a design on a smooth, flat stone with greasy crayon. Then he dampened the stone, and the water stuck only to the parts not covered by the design. Next, he inked the stone, and the ink stuck only to the design. He then pressed paper against the stone and transferred the image to the paper.

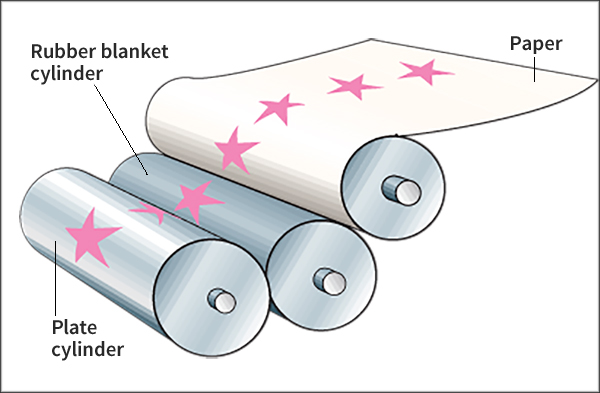

In offset lithography, thin metal plates have replaced Senefelder’s stone, and the images are put on the plates photographically, or electronically using a laser. The inked images do not print directly on the paper that is fed through the press. Instead, the images are offset (transferred) to a rubber-covered cylinder, called a blanket cylinder, which in turn offsets them to the paper or other substrate.

Almost anything can be printed by offset lithography. The process is used for such items as books, cards, magazines, stationery, cans, cartons, business forms, labels, and newspapers. Nearly half of all printing today is done by offset lithography.

Offset printing plates

may be either negative-working or positive-working. Negative-working plates are made photographically from negatives assembled during page makeup. The negatives are held by vacuum pressure against a metal plate with a coating that hardens when exposed to light. Powerful lamps shine light through the transparent parts of the negatives, hardening the image areas on the plate. The plate is treated with a solution of developer and lacquer. The lacquer adheres only to the image areas. The plate is washed, and a gum is applied to thoroughly cleanse the nonimage areas so they will reject any ink. During printing, only the lacquered areas accept ink. Positive-working plates require film positives or specially treated paper. They are made by photographing negatives or by printing the negatives on film or paper.

Some offset plates can receive images directly in an imagesetting or platesetting device, eliminating the use of paper or film. This process is referred to as computer-to-plate or direct-to-plate. Images are transferred as a digital code. This code is then read by a laser platesetter, which then produces the printing plates.

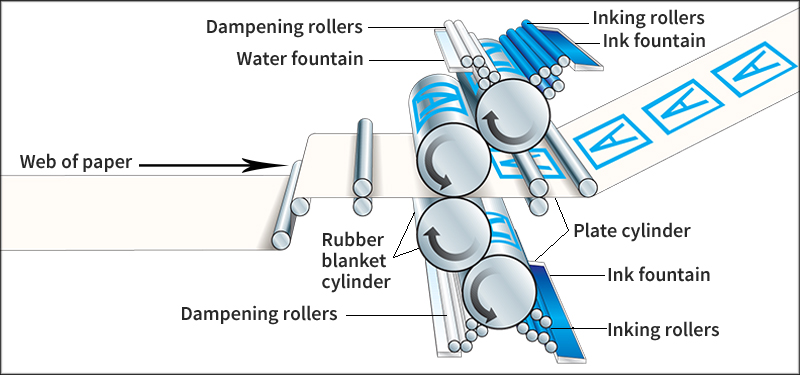

Offset presses

are rotary presses—that is, they use revolving cylinders to hold both the printing plate and the substrate. An offset press prints from a curved printing plate clamped to a rotating plate cylinder. As the cylinder rotates, it presses against dampening rollers, which wet the plate so the nonprinting areas will repel ink. The cylinder next passes against inking rollers, and ink sticks only to the image areas. The turning plate cylinder then offsets the inked images onto a rotating blanket cylinder, a cylinder covered with a rubber blanket. The blanket cylinder offsets the images onto the paper or other substrate carried by an impression cylinder. This assembly of rollers and cylinders is known as a printing unit.

In a sheet-fed offset press, sheets of paper pass through the printing unit one at a time. Sheet-fed presses have one, two, four, or more units. In presses with multiple printing units, each unit prints a different color. Some sheet-fed presses are perfecting presses—that is, they print both sides of the paper in a single pass.

After a worker sets up the press, sample copies are printed. Then, in a process called makeready, the worker makes adjustments to get the best impression. If more than one color is being printed, the register (alignment) of the colors is adjusted during makeready.

Most web-fed offset presses are multicolor perfecting, blanket-to-blanket presses. These presses do not use impression cylinders. The web of paper passes between the blanket cylinders of two units. The blanket cylinder of each unit serves as the impression cylinder for the other. The paper is printed on both sides as it goes between the blankets.

Next, the paper is gathered onto another roll, or it is cut and folded into groups of pages called signatures. Some presses are fitted with high-speed staplers, called stitchers, that produce finished, stapled magazines. Other presses have gluers and cutters that create envelopes or three-dimensional printed pieces, such as stand-up displays or pop-up greeting cards.

Offset presses are fast. Sheet-fed presses can print up to 250 sheets per minute. Some web presses can run at speeds of 3,000 feet (900 meters) per minute.

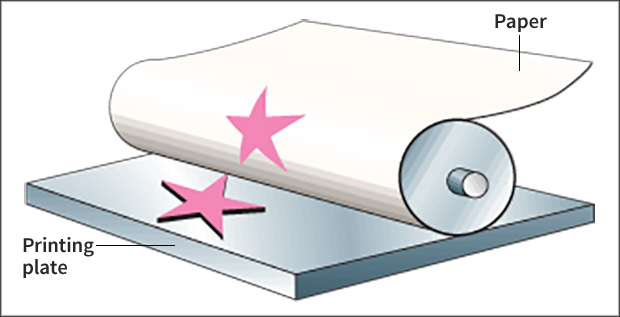

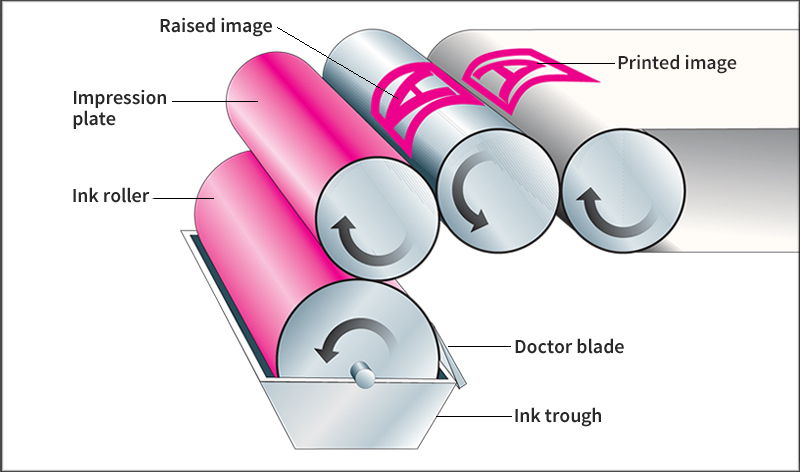

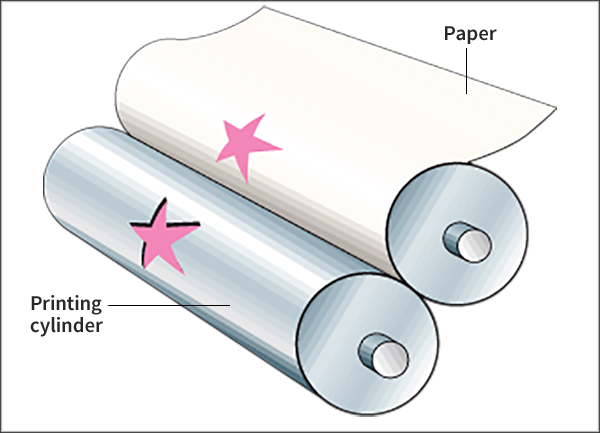

Relief printing

is the oldest method of printing. More than 1,300 years ago, people in East Asia printed from wood blocks. They carved the nonprinting areas from the surface of a piece of wood, leaving characters and designs in relief (raised). They inked the raised surface, placed a sheet of paper on the block, and transferred the ink to the paper by rubbing the back of the sheet. There are two common forms of relief printing used today, flexographic printing and letterpress printing.

Flexographic printing.

Flexographic plates are made of rubber or soft plastic. Their softness makes them especially useful for printing on materials that should not be squeezed too hard, such as corrugated paper, foils, and plastics. Almost anything that can go through a web press can be printed flexographically. Such items include newspapers, cardboard cartons, and gift wrap.

Flexographic plates can be made photographically or by laser. In the photographic method, a metal or plastic sheet is exposed to ultraviolet or other special light through a negative. The sheet is chemically treated so that the part exposed to light hardens. The nonimage areas remain soft and can be washed away, thereby creating a plate with raised image areas. This plate is pressed into cardboard or soft plastic, leaving a negative relief of the image. The negative relief is then used as a mold or mat. A sheet of rubber or plastic is pressed into the mold under heat and pressure, forming a positive relief plate. The other method for making flexographic plates uses a laser to cut an image from a specially treated rubber plate or cylinder.

Flexographic presses use a single roller to apply ink to the printing plate. A doctor blade scrapes excess ink from the roller, which rotates inside an ink fountain. Flexographic presses squeeze the paper or other substrate between an impression cylinder and a plate cylinder. The impression pressure is adjusted to the minimum needed to get a clear reproduction. This light impression is called a kiss impression.

Letterpress printing.

A letterpress printing press uses plastic or metal relief printing plates or type forms. A type form consists of type and other material locked in a metal frame for printing. Letterpress dominated printing from its invention in the mid-1400’s, until the mid-1900’s. Letterpress declined in popularity largely because its text and halftone image quality is not as good as that produced by offset. In addition, letterpress makeready tends to take a long time and waste much paper. Today, the letterpress process is used only by specialty printers. Most items that were once printed by letterpress are printed by offset today. Others, including some newspapers, are produced by flexography.

Letterpress printing plates are made photographically, in a process similar to that used for flexographic plates. The plastic or metal plates are chemically treated so that the surface hardens in image areas that are exposed to light. The nonimage areas remain soft and can be removed with water, a chemical solution, or a blast of air. Removing these areas leaves the image in relief. The plate is then hardened further before printing.

Letterpress printing presses include platen, flat-bed, and rotary presses. Platen presses have two main parts. A bed holds the type form or printing plate, and a metal plate called a platen holds the paper to be printed. The two parts are both flat, and they are joined together like a clamshell. Rollers ink the form or plate as a sheet of paper is fed to the platen. The platen then swings against the printing surface and prints the sheet as the rollers roll back to get more ink from an inking plate. As the platen swings back, the printed sheet is released.

Flat-bed presses move the type form, which rests on the flat bed of the press, against a rotating impression cylinder. The paper, which is attached to the cylinder, is printed as it rolls over the form.

Rotary presses for letterpress printing are similar to those used in flexographic printing. Rotary presses are used today for specialty letterpress printing.

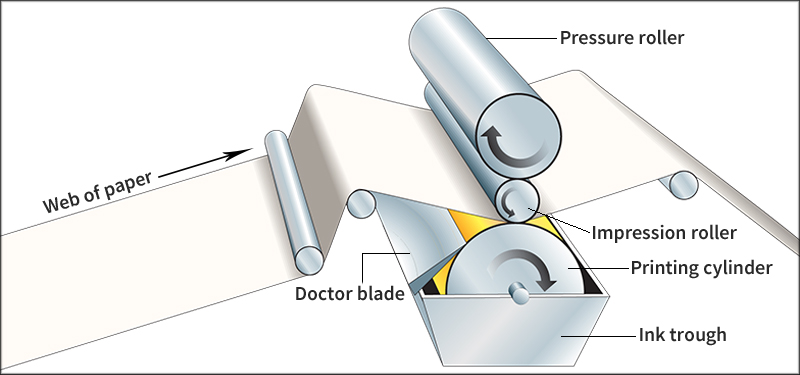

Recess printing,

also called gravure printing, is an intaglio << ihn TAL yoh or ihn TAHL yoh >> method of printing. The words, pictures, or designs to be printed are sunk into a printing or plate. Gravure is used to print a wide variety of items. They include the magazine sections of newspapers, catalogs, postage stamps, stock certificates, floor tiles, wallpaper, boxes, and gift wrap.

Gravure cylinders.

Most commercial recess printing processes use printing cylinders rather than plates. This process is also called rotogravure. Most gravure cylinders are made by electromechanical engraving. In this process, an electronic scanner scans the original copy or offset film. The scanner sends signals to a computer, which directs a machine equipped with diamond-pointed cutting tools called styluses. The styluses cut thousands of little pits called cells into the copper covering of the cylinder. The cells vary in area and depth. On the printing press, the deepest cells hold the most ink and print the darkest tones. The shallowest cells hold the least ink and print the lightest tones.

Another method of gravure involves putting images on the printing cylinder photographically. The copy to be printed is photographed and made into film positives. The halftone method is not used. The positives are then assembled as they are to appear in print. Next, the images on the positives are transferred to the printing surface through the use of carbon tissue, a sheet of paper covered with light-sensitive gelatin. The carbon tissue is first exposed under bright light to a screen called a gravure screen to create a grid of light-hardened lines and softer squares on the tissue. Then the carbon tissue is exposed to the film positives. The gelatin hardens further according to how much light passes through the positives. The gelatin becomes hardest and thickest where the most light passes through.

The exposed tissue is placed gelatin side down on a heavy copper-plated cylinder. The tissue is developed in water, and the paper backing is stripped off. A layer of gelatin made up of tiny squares of varying thickness is left standing on the copper. The cylinder is then bathed in a corrosive solution. The solution eats through the gelatin squares and bites small cells into the copper. It quickly penetrates the thin squares and bites deepest into the cylinder in these areas, which thus print darkest. This process is known as etching.

The direct transfer method of gravure does not use carbon tissue. Instead, a light-sensitive coating is applied directly to the cylinder and exposed to light through a halftone positive film.

Modern methods use a computer to control a laser that engraves the image directly onto the cylinder. The computer issues its instructions using information from digital files of text and graphics.

Gravure presses

are usually web-fed rotary presses. Rotogravure presses can run at speeds of more than 3,000 feet (900 meters) per minute. In most gravure presses, the printing cylinder rotates with its bottom edge in a trough of ink. As the cylinder turns, the cells fill with ink. A doctor blade wipes the surface clean so that the ink remains only in the cells. An impression roller presses paper against the printing cylinder and into the cells. The pressure transfers the ink in each cell to the paper. This transfer is assisted by the addition of an electrical device that creates a negative electric charge in the gravure cylinder and a positive charge on the impression cylinder. Opposite charges attract, and those on a gravure press make the ink inside the cells jump to the paper as it passes by.

Digital printing,

also called electronic printing, is done with desktop printers or copying machines. A desktop printer requires a stream of digital data, and a copier requires an original document.

A laser printer is used with a computer and digital files of text and graphics. It uses a laser to give a negative electric charge to a cylinder in a pattern that corresponds to the text and graphics to be printed. Positively charged toner is attracted to the negatively charged areas. A piece of paper is pressed onto the cylinder, where it receives the toner. The paper is then passed through heated fuser rollers, which cause the toner particles to permanently adhere to the paper.

Copying machines are used to duplicate printed documents. In most copiers, the original copy is scanned and converted to a pattern of dots. A laser transfers this pattern to a drum as electric charges. The copier then uses toner, paper, and fuser rollers in the same way that a laser printer does. Some older copiers use reflected light from a special bulb to focus the copy through a lens onto a negatively charged drum. The image forms on the drum as a pattern of positively charged particles.

Some printers and copiers use inkjet technology. An inkjet squeezes small drops of ink onto a slowly moving sheet of paper to produce an image. Or it uses an array of nozzles to eject the ink continuously on a fast-moving web of paper.

Digital printing requires a new image to be created on the drum for each copy. Thus the process is capable of producing personalized direct mail, on-demand (one at a time) publications, and other customized printed products. All other printing methods are better suited for print runs of over 500 copies.

Other printing processes

include screen printing and collotype printing.

Screen printing

requires a stencil and a fine cloth or screen. The stencil carries the design to be printed. Ink is squeezed onto the printing surface through the areas of the screen not covered by the stencil. The stencil can be cut out of paper. Or it can be made by tracing a design directly on the screen and blocking out the nonprinting areas with glue or lacquer. A stencil can also be made by giving the screen a light-sensitive coating and putting the design on it photographically or by laser.

The screen printing process can be used to print on paper, glass, cloth, wood, or almost any other material. It can print on objects of various sizes and shapes, including draperies, bottles, toys, and furniture. Screen printing can be done using automatic or hand-operated presses. Screen printing is also called silk-screen printing or serigraphy.

Collotype printing

is similar to lithography. A light-sensitive coating of gelatin is put on a metal or glass plate. The gelatin is exposed to light under an unscreened negative that carries the image to be printed. The light passes through the negative, hardening the gelatin to varying degrees. The plate is then soaked in a solution of water and glycerin. The hardest parts of the gelatin absorb the least solution, and the softest parts absorb the most. On the printing press, the hardest, driest parts accept the most ink and print the darkest tones. The softest, wettest parts accept the least ink and print the lightest tones. Collotype is sometimes used to print post cards, greeting cards, posters, and high-quality reproductions of paintings.

Printing in color

Lithography, relief printing, recess printing, and digital printing can reproduce anything in color—from comic strips to masterworks of art. There are two chief kinds of color printing: (1) process color printing and (2) flat color printing.

Process color printing

is used mainly to reproduce color copy that contains shades or tones. Such copy includes oil paintings, water-color paintings, and color photographs. Process color printing uses tiny dots of transparent ink in the colors yellow; magenta << muh JEHN tuh >> , a purplish-red; cyan << SY an >> , a blue; and black. With only these four colors of ink, process color printing can reproduce almost any color and tone. Sometimes, colors other than these are used to achieve special effects.

Most printing operations use an electronic scanner to separate the colors in the copy. A scanner produces digital files that represent the yellow, magenta, cyan, and black components of the copy. If a halftone dot pattern is required, a scanner can generate such a pattern for each color. In printing, some of the tiny dots fall close together, some overlap, and some fall on top of others. To the viewer’s eye, the colors of the dots appear to be all the colors and shades of the original copy. For example, what the eye sees as green is an area of tiny cyan and yellow dots. The digital files produced by the scanner can be stored, and they can later be output to digital printers, imagesetters, or platesetters.

In color lithography, relief printing, and recess printing, after the separations have been made, the steps follow the standard procedures for making printing plates or cylinders. On a four-color press, there are four plates. Each plate has its own supply of either yellow, magenta, cyan, or black ink. On a four-color rotary press, paper passes from one set of cylinders to the next, picking up the different colors and emerging from the press fully printed.

Before the development of scanning technology, a camera was used to photograph the copy four times to create a separation negative of the yellow, magenta, cyan, and black in the copy. Each time, a different colored filter was used to block out all colors from a negative except the desired one. Printers used the separation negatives to produce relief or offset plates, or gravure plates or cylinders.

Flat color printing

is used chiefly to print line copy in solid colors. Such copy includes diagrams, headlines and other type matter, and trademarks on stationery. Flat color printing is simpler than process color printing. Separate plates are made for each color of opaque ink. Halftone screenings are not used.

History

The history of printing can be traced back thousands of years, to when people in the Middle East learned to press carved designs into wet clay. More than 2,000 years ago, the Chinese invented paper. By the 700’s, the Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans were using block printing. They carved symbols and pictures on wood blocks, inked the raised images, and transferred the ink to paper.

The invention of movable type.

About 1045, a Chinese printer named Bi Sheng (Pi Sheng) made the first movable type. He made a separate piece of clay type for each Chinese symbol or character. But the Chinese language required so many different characters for printing that the method was difficult and fell into disuse. Printers found it easier to print from wood blocks.

While the people of East Asia were printing from wood blocks, the people of Europe still copied books by hand. Many monks spent their lives copying books with quills and reeds. In the late 1300’s, Europeans discovered wood-block printing. The earliest dated European wood-block print is a picture of Saint Christopher, printed in 1423. About this time, Europeans began to produce block books by binding prints together.

Meanwhile, a major revival of art and learning called the Renaissance was sweeping through Europe. The great desire for learning created a huge demand for books that hand copying and block printing could not satisfy. Movable type solved the problem.

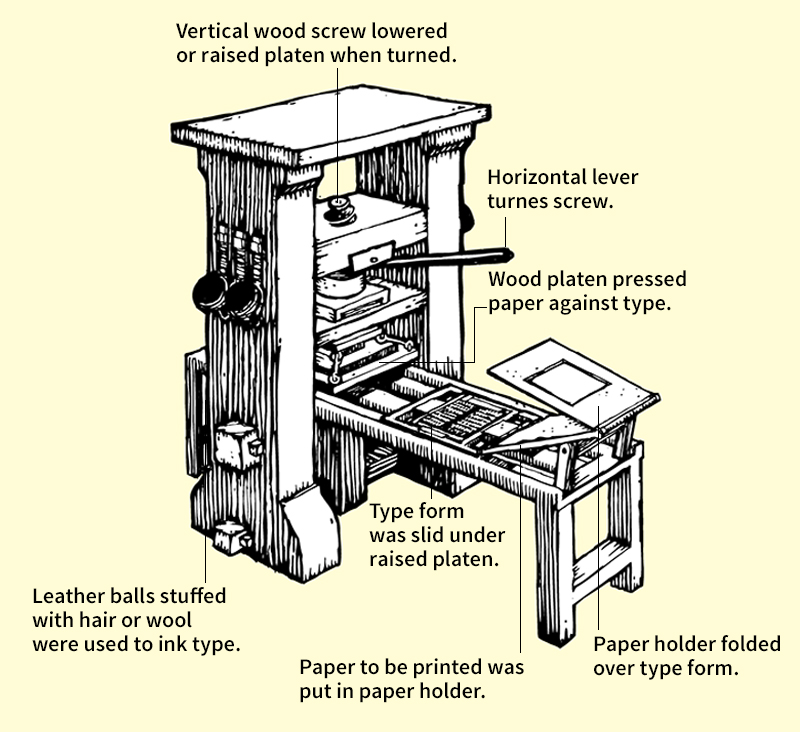

Printing as we know it today began about 1440 with the first use of movable type in Europe by Johannes Gutenberg and his associates in Germany. Gutenberg brought together several inventions to create a whole new system of printing. He made separate pieces of metal type, both capitals and small letters, for each letter of the alphabet. He assembled the pieces of type in a frame to form pages. Finally, his press, based on the idea of a wine press, became the first printing press in Europe. Gutenberg had found it hard to produce evenly printed copies by pressing the paper against the type by hand. By turning a huge screw on the press, he could put uniform pressure on the paper. The Gutenberg press could print about 300 copies a day. By 1456, the famous Gutenberg Bible was completed.

Many people feared that the new art of printing was a “black” art that came from Satan. They could not understand how books could be produced so quickly, or how all copies could look exactly alike. In spite of people’s fears, printing spread rapidly. By 1500, there were more than 1,000 print shops in Europe, and several million books had been produced.

Early printing in North America.

In 1539, an Italian printer, Juan Pablos (Giovanni Paoli), set up a print shop in Mexico City. This was the first print shop in North America. In 1639, Stephen Daye and his son Matthew set up the first press in the American Colonies, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Printing spread quickly through the colonies, though the colonial authorities often placed strict controls on printers. The early printers were America’s first publishers of newspapers, books, and magazines. In 1704, John Campbell established The Boston News-Letter, the first regularly published paper in the colonies. In 1751, Bartholomew Green of Boston set up Canada’s first print shop in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Green died that same year, and his former assistant, John Bushell, took over the shop. In 1752, Bushell began publishing the Halifax Gazette, Canada’s first newspaper.

New presses and typecasting machines.

There were few changes in the printing press from Gutenberg’s time until the 1800’s. An English nobleman, the Earl of Stanhope, built the first all-iron press about 1800. In 1811, the German printer Friedrich Konig invented a steam-powered cylinder press. This press used a revolving cylinder that pressed the paper against a flat bed of type. The Times of London used the press for the first time in 1814. It could print 1,100 sheets per hour.

In 1846, Richard M. Hoe of the United States, a manufacturer of printing presses, invented the rotary press. He attached type to a revolving cylinder and used another cylinder to make the impression. The first Hoe presses printed 8,000 sheets per hour. Later models turned out 20,000 sheets per hour. In 1865, William A. Bullock, an American inventor and machinist, found a way to print from a continuous roll of paper and invented a high-speed web-fed rotary press.

Until the 1880’s, printers set all type by hand, just as Gutenberg had done over 400 years before. In 1884, Ottmar Mergenthaler, a German instrument maker living in the United States, patented the Linotype. This machine uses a keyboard to cast a full line of type in one piece of metal, thus eliminating the need for hand-setting. In 1887, Tolbert Lanston, an American inventor, developed the Monotype, which casts and sets separate pieces of type.

Developments in platemaking.

In 1826, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, a French physicist, produced the world’s first photograph. This achievement, and further developments in photography, made possible photoengraving, the halftone process, and photolithography and modern offset printing.

In 1852, William H. Fox Talbot, an English photographer, patented photoengraving. Two American photoengravers, Max and Louis Levy, perfected the halftone screen in the 1880’s. Alphonse Louis Poitevin, a French chemist, engineer, and photographer, invented photolithography in 1855. By the late 1800’s, offset presses appeared in Europe. These early presses were used to print tin sheets for making cans and boxes.

About 1905, Ira Rubel, U.S. papermaker and printer, accidentally discovered the offset method for printing on paper. While running his press, Rubel unintentionally transferred the inked images onto the rubber-covered impression cylinder, instead of onto paper. Then, when he ran paper through the press, the impression cylinder offset the images onto the paper. Rubel noticed that the offset images were unusually sharp. Improvements in the offset press followed, and offset printing quickly came into general use.

The electronic age.

Since the 1930’s, more advances have been made in printing than in all the years since Gutenberg. By the mid-1940’s, advances in photolithography and offset printing made it possible to print with better quality, consistency, and cost-efficiency than the relief process could offer. The combination of photographic processes and offset printing brought more complex illustrations and photographs to printed pieces, as well as more brilliant and lifelike colors. By the 1960’s, photoengraving and offset printing had become so simplified that certain kinds of printing could be done in minutes, giving rise to a new kind of commercial printing called quick printing.

Desktop publishing began in the mid-1980’s. New computers, computer printers, and software enabled people to design, edit, and print material that traditionally would have been produced on printing presses. In the late 1900’s, inventors developed processes for putting images onto paper and other materials directly from computer files, without an intermediate step.