Rain forest is a woodland of tall trees growing in a region of plentiful rainfall. Rain forests include some of the world’s richest ecosystems. An ecosystem consists of a community of living things and the nonliving things on which they depend.

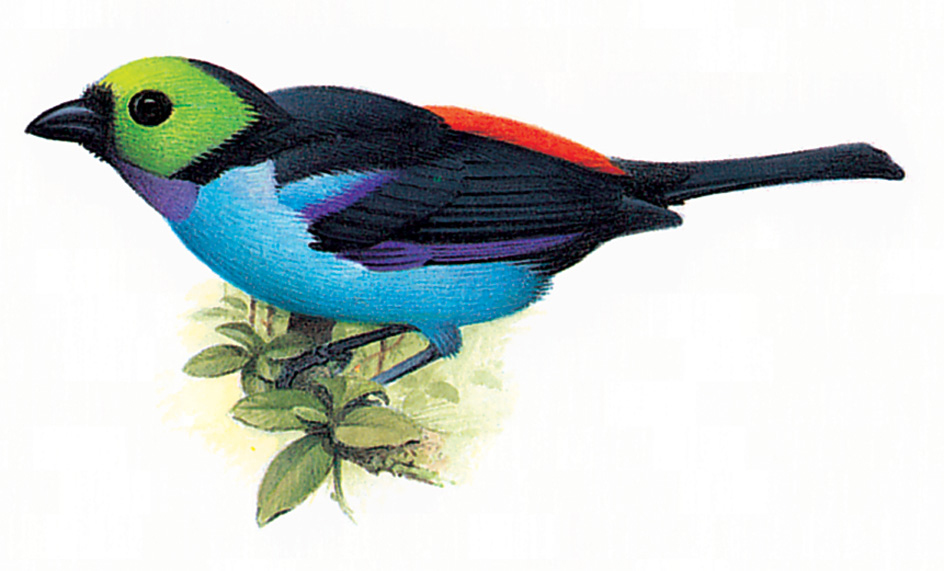

In a rain forest, rain, temperature, and humidity combine to create excellent conditions for plant growth. The trees of a rain forest often grow to great heights. They support a dense community of nontree plants, including epiphytes, which grow on other plants and get moisture from the air. Rain forests support an equally spectacular diversity of animal life, from beautiful butterflies and swarming ants to showy birds-of-paradise and brilliantly colored poisonous frogs.

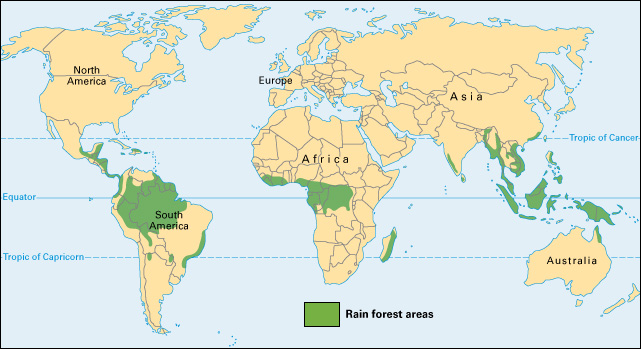

There are two major types of rain forests: tropical and temperate. Tropical rain forests are those found near Earth’s equator, between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn. Tropical rain forests occur in Africa, Australia, Central America, South America, Southern Asia, and the South Pacific islands. Temperate rain forests are those found outside the tropics. They appear in certain coastal regions on all the continents except Antarctica, as well as in island nations such as New Zealand. In rare instances, small areas of temperate rain forest occur away from the oceans.

Loading the player...Tropical rain forest sounds

A key feature of rain forests is an amazing biodiversity, the richness of variation among living things. For example, some areas of the Peruvian Amazon rain forest have about 10 times as many species (kinds) of trees as do similarly sized areas of North American temperate forest. The small rain-forested country of Panama has more bird species than all the United States and Canada combined. Diversity also appears on smaller scales, with over 40 species of epiphytes found growing on the branches of a single tree in Nicaragua. Each epiphyte species has several species of insects, birds, or bats that feed on or pollinate it, further multiplying biodiversity.

Rain forests provide incredible benefits to the planet. South America’s Amazon River and rain forest, for example, hold around one-fifth of Earth’s fresh water, continuously purifying the water through cycles of rain and evaporation. Rain forest trees also store large amounts of the element carbon, helping to limit levels of carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere. Excess carbon dioxide can trap heat near Earth’s surface, contributing to global warming—an observed increase in Earth’s average surface temperature. Rain forests have benefited people around the world with such food plants as bananas, mangoes, and pineapples. Rain forest organisms (living things) provide a vast supply of potential medicines.

Many different cultures have called the rain forest home. These groups rely on traditional knowledge of rain forest plants and animals to survive in a challenging environment. In the last four centuries, however, new cultures have come in contact with rain forest ecosystems, taking a great toll on the rain forests. In many places, people are rapidly cutting down rain forests for farmland. Less than 50 percent of the area covered by tropical rain forests in 1500 still has trees today. Temperate rain forests are also being destroyed at a rapid pace. Conservationists and others must work together if we are to preserve these vanishing ecosystems.

Characteristics of rain forests

Climate.

Scholars classify an area as rain forest mainly by the amount of rainfall it receives. By definition, a tropical rain forest gets at least 100 inches (250 centimeters) of rain each year. Temperate rain forests receive about 80 inches (200 centimeters) of annual rainfall.

Tropical rain forests generally receive rain the year around, without any long dry periods. The wettest rain forests, such as those near the Andes Mountains in Ecuador and Colombia, receive over 30 feet (9 meters) of rain a year. In these areas, rain falls on most days.

Tropical rain forests have steady temperatures throughout a typical year. They also have high daytime and nighttime temperatures. In the Amazon rain forest, for example, daytime temperatures are typically over 86 °F (30 °C), and nighttime lows are around 75 °F (24 °C).

As large, rain-carrying clouds float by, conditions in a tropical rain forest often change from intense tropical sunshine to overcast clouds to a drenching downpour and back again in short cycles. The ample heat, humidity, and sunlight are ideal for plant growth. Beneath the rain forest canopy (the tops of the trees), however, most light is blocked. Plants struggle for light, but fungi thrive.

Soil

with high clay content is most common in rain forests. But some areas, including parts of the Amazon, have sandy soils.

With hearty plant growth and a wealth of decaying material from living things, it may seem that rain forest soils should be rich and productive. But in reality, typical rain forest soils have few nutrients. Almost all rain forest soils have scarce nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, the key nutrients for plant growth.

Rain forest soils are poor because rain forests recycle nutrients efficiently. When an organism dies, rain forest fungi, bacteria, and small animals break down the dead tissue rapidly. The nutrients and carbon from a decaying tree or dead bird, for example, may never enter the soil. Instead, they are taken up by other living things.

Structure and growth.

Tall trees and jungle vines serve as the most visible characteristics of rain forests. But such plants are part of a more intricate structure unique to each individual ecosystem. In the interior of a tall forest, the canopy usually stands between 100 and 130 feet (30 and 40 meters) above the ground. Enormous emergent tree species rise above the canopy to heights of 160 to 260 feet (50 to 80 meters). In undisturbed areas, the canopy forms a nearly continuous cover, with the tops of trees fitting together like puzzle pieces.

When a tree falls, a complex cycle of plant growth begins. This cycle helps maintain the structure of the forest. It also contributes to diversity, by encouraging the growth of trees with different lifestyle strategies. There are three kinds of tree of particular importance to growth and structure: (1) pioneers, (2) shade-tolerant hardwoods, and (3) sun-lovers.

Pioneer species grow rapidly and are often first to colonize a new sunny spot. But they are typically short-lived. Pioneer species can grow as much as 16 feet (5 meters) in a single year. They have soft trunks and grow poorly in shade.

Shade-tolerant hardwoods, on the other hand, spend years to decades waiting in the understory, a shady area below the canopy. They grow slowly until a break in the treetops gives them a chance to reach the canopy. Once they reach the canopy, they can live for centuries. They are supported by their thick wood and strong branches.

The third group, called sun-lovers or heliophiles, falls somewhere in between. They rely heavily on canopy openings for light. The sun-lovers grow at a moderate rate and are strong enough to live for long periods.

Trees form only a small part of the rain forest structure. Epiphytes, vines, and woody lianas hang from the trees, often weaving multiple trees together. Palms are typically not as tall as the hardwoods and form multiple levels of the rain forest structure, from a lower treetop level called the sub-canopy to the understory. Woody shrubs and herbaceous (non-woody) plants dominate the understory.

Plant life

of all sizes, from tiny mosses to enormous trees, makes up the majority of a rain forest’s living tissue, called biomass. Flowering trees dominate inland tropical rain forests, whereas some island rain forests feature a large diversity of such cone-bearing gymnosperm plants as Araucaria and cycads. Temperate rain forests have a large number of cone-bearing trees.

Mosses and similar plants of ancient ancestry are incredibly important in temperate rain forests, making up much of the understory. Mosses today play a small role in tropical forests. Prehistoric tropical rain forests, on the other hand, were dominated by mosses and by giant, treelike club mosses, which made up the canopy.

Ferns are another ancient group of plants that play a major role in rain forests. They may grow along the ground, as dangling epiphytes perched on tree branches, and even as enormous tree ferns with hard trunks. Such tree ferns can reach heights of more than 65 feet (20 meters). Ferns reproduce using tiny spores and can disperse (scatter) over great distances. Some modern fossil fuels come from the remains of ancient rain forests with many tree ferns. Fossil fuels are fuels such as coal, oil, and natural gas developed from the remains of ancient living things.

Gymnosperms, such as firs, spruces, and pines, make up the majority of trees in temperate rain forests. But they play only minor roles in most tropical rain forests. Some tropical forests of the Pacific Islands, however, rely heavily on such distinctive gymnosperms as the Norfolk Island pine.

Dicots make up the majority of the biomass in tropical rain forests. Dicots are flowering plants with two cotyledons (leafy parts within each seed). Most large trees are dicots, including such giants as the kapok of Africa and the American tropics. The legumes are particularly important in tropical rain forests. Legumes are relatives of the pea. They grow in a vast variety of forms from small plants to giant woody vines to enormous emergent trees. Legumes can capture nitrogen from the air and turn it into a usable form with the aid of bacteria. This ability enables legumes to dominate many rain forest regions, where nitrogen is scarce in the soil.

Monocots are also important in rain forests. Monocots are flowering plants with one cotyledon. More kinds of orchids grow in the rain forest than any other type of plant. Because of their small size, however, orchids make up only a tiny fraction of rain forest biomass. Other monocots with spectacular flowers are the bird-of-paradise plant, the Heliconia, and the ginger family. Palms are an important monocot in tropical rain forests. The widely diverse Araceae family of plants, which includes dumb cane, peace lily, Philodendron, and Pothos, appears in both ground-growing and climbing forms.

Animals.

An astonishing number of animal species live in rain forests. Millions of species of arthropods (animals with jointed legs and no backbone) make their home in tropical rain forests. Most are insects, with beetles contributing the greatest number of species. Some beetles, such as Goliath and Hercules beetles, dwarf most other insects. Dung beetles play an important role by moving nutrient-rich dung (solid waste) dropped by larger animals, helping to fertilize the rain forest.

Loading the player...Animals of tropical forests

Beetles are the most diverse rain forest animals, but ants are often considered the most important. Ants serve an incredible variety of functions in rain forests. Massive swarms of army ants raid the forest floor to catch prey. They can overwhelm and consume nearly any insect or other small animal in their path. Acacia tree ants live on acacia trees, getting all that they need from the tree. In return, the ants fend off such intruders as grasshopper pests and vines that compete for sunlight.

Other arthropods, such as spiders, scorpions, millipedes, and even land-dwelling crabs, make their home in tropical rain forests. Such strange, unique groups as the velvet worms—which somewhat look like many-legged slugs—inhabit rain forests as well.

Both rivers and lakes form important parts of tropical rain forests. Such rain forest waters are home to the majority of Earth’s freshwater fish species. Tropical fish are not limited to rivers and lakes. They may enter the rain forests during floods, when, for example, large piranha relatives such as the pacu eat fruits fallen from trees. Some rain forest species, such as walking catfish, are known to crawl over land using their front fins. Freshwater stingrays are among the few cartilaginous fishes—that is, fish with a skeleton made of cartilage instead of bone—found outside the oceans. Amazonian stingrays are most closely related to stingrays of the Pacific Ocean. This and other evidence suggests that the Amazon was connected to the Pacific Ocean million of years ago, before the Andes Mountains arose.

Rain forests also house more types of land vertebrates (animals with backbones) than do any other ecosystems. Among amphibians, frogs are incredibly diverse, with land-living, water-living, and tree-living forms found in the rain forest. Brightly colored poisonous frogs are found in the rain forests of the American tropics, of Madagascar, and even of Australia. These frogs make up three distinct groups that evolved (developed over time) independently. All three groups use bright colors to warn away predators (hunting animals) and typically get their toxins from foods they eat. Salamanders are one of the few groups that are less diverse in the tropics.

Thousands of reptiles live in the rain forests. They include a wide variety of lizards, snakes, and turtles. Some reptiles have bizarre adaptations for rain forest living. The chameleon, for example, can change colors by altering the structure of its skin cells, with different colors serving as social signals to other chameleons or as camouflage. The basilisk lizard can run on the surface of water. Rain forests are home to the world’s largest snakes, including the pythons of Asia and Africa and the anacondas and boas of the Americas. Some venomous (poisonous) snakes include the deadly king cobras of Asia, the spectacular vipers of Africa, the aggressive fer-de-lance of the American tropics, and a number of deadly Australian species. Among turtles, the mata mata of the Amazon and Orinoco river systems is notable for its fringed head, which is easily camouflaged among fallen leaves. The majority of the world’s crocodilians (crocodiles, caimans, and related animals) are found in tropical rain forest waters.

Rain forest birds come in all sizes and colors and fulfill a great range of ecological roles. Some birds help control insects, others disperse seeds, and still others serve as top predators (hunting animals at the top of the food chain). New World tanagers have magnificent coloration. Birds-of-paradise feature bizarre plumages. Other well-known rain forest birds include parrots and toucans. Parrots are found in all tropical rain forests. Most parrots specialize in eating seeds and aid in seed dispersal. In the Americas, hummingbirds have evolved as important plant pollinators. They appear to favor the color red, leading to more red flowers in the rain forests that hummingbirds inhabit. Many tropical bird species nest in hollows in trees, rather than among the branches. The limited number of such hollows is thought to limit populations of some tropical bird species. Tropical rain forests also attract a wide range of migratory birds wintering far from their nesting grounds.

Around half of the mammal species in a tropical rain forest are bats, ranging from tiny insect-eaters to the enormous flying foxes, which eat fruit. Flying foxes can have wingspreads up to 6 1/2 feet (2 meters). Like birds, bats help to control insects and disperse seeds. Some bat species even serve as pollinators. Large, white rain forest flowers often serve to attract pollinating bats.

Although less diverse than the bats, nonflying mammals remain ecologically important in the rain forest. Large mammals are the least numerous, but they play an outsize role due to their size and strength. In African and Indian rain forests, for example, elephants can uproot trees, making room for new growth. Such large seed-eaters as tapirs serve as the only species that can crack hard nuts. Mammals that live in the rain forest trees include such primates as monkeys and lemurs as well as tree-dwelling marsupials (pouch-bearing mammals) in Australia. Rain forests are home to the world’s smallest primates, including the pygmy marmoset of the Amazon and the Philippine tarsier, each less than 6 1/2 inches (17 centimeters) in length. Some mammals—including pumas, tigers, and white-tailed deer—live in both temperate and tropical regions. These mammals are generally smaller in the tropics, perhaps because they have less need of mass to conserve body heat.

Ecology

Many features of rain forests help to enable a great diversity of species to live close together. For example, the structural diversity of plants, ranging from small plants of the understory to giant trees, creates a variety of places for organisms to live. Many species live their entire lives in the forest canopy, never even touching the ground.

Many rain forest species have developed relationships with other species that benefit both, called mutualisms. Such relationships contribute to diversity. A tree such as Dipteryx oleifera, for example, sometimes called the giant tropical almond, is home to many species, feeds many species, and relies on a whole host of species to survive and reproduce. Like other legumes, Dipteryx trees make use of Rhizobium bacteria to capture nitrogen from the air. The trees also rely on fruit-eating bats and such birds as great green macaws to pick their fruits, dispersing the seeds. They rely on mammals, such as agoutis, to further disperse the seeds that birds and bats drop to the forest floor. At least thirteen different kinds of bees help pollinate Dipteryx trees. All these species live on, around, or with the help of one tree, and there are around 16,000 tree species in the Amazon alone.

For a land ecosystem to be productive, it must have access to water and to energy from sunlight. The abundance of water and sunlight in tropical rain forests makes them the most productive land ecosystems on Earth. High productivity enables rapid tree growth, a high level of interdependence among species, and the capture of great quantities of carbon in tree trunks.

Rain forests around the world

Rain forests exist on all continents with tropical regions, but their characteristics differ greatly from continent to continent. Distinct major regions are the New World tropics or Neotropics—which includes the North and South American tropics and the Caribbean region— and the African, Southeast Asian, Southeast Asian, and Australian tropics. The wettest rain forests typically occur at the windward base of mountain chains. In such areas, warm, moist air cools as it rises into the mountains, dropping much of its moisture as rain.

In the Neotropics, the Amazon rain forest is one of the largest continuous land ecosystems. The only forests larger are the vast boreal forests of Canada and northern Asia. The Amazon is more diverse than the rain forests of Central America or the Brazilian Atlantic Forest.

Legume trees dominate neotropical rain forests. These forests also have many large palm species. Neotropical rain forests are more common on the Atlantic side, where easterly winds blow moist, warm air off the Atlantic Ocean. The Amazon, however, stretches nearly the width of South America from the Atlantic Ocean to the Andes mountains, near the Pacific Ocean.

In Asia, easterly winds bring rain from the Pacific Ocean, watering tropical rain forests in Southeast Asia. The islands of the South Pacific and such mainland countries as Vietnam, Thailand, and Myanmar are home to incredibly diverse rain forests. Scholars divide the South Pacific rain forests into two distinct types along a boundary known as the Wallace Line. It is named for the British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, who first described it. Islands east of the Wallace line, such as New Guinea and Sulawesi, have different groups of species than those west of the line, such as Borneo and the Philippines. Southeast Asian rain forests are dominated by trees from a family called the Dipterocarps, but they also have a high diversity of palms and other trees.

The Indian subcontinent has rain forests on the western coast of India and on the eastern side in Bangladesh and extreme east India. The forests of the eastern side are ecologically similar to southeast Asian rain forests. But the rain forests in the Western Ghats region are different. Both regions feature Asian elephants and have the Bengal tiger as a top predator. But they differ in terms of plants, birds, bats, and other living things.

The tropical rain forests of Africa are found in a fairly narrow band stretching along the equator from the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the center of the continent. The Congo Basin houses a vast rain forest sometimes called the Amazon of Africa. Africa and South America were once much closer together, and as a result their rain forests share many common features. Legume trees, for example, are important in both regions. But African rain forests have many unique life forms, including lowland gorillas and forest elephants.

Australia’s tropical rain forests are limited to a thin band along the eastern coast of the continent. They share some common features with the southeast Asian rain forests, but the only native mammals in Australia’s rain forests are marsupials and bats.

The major temperate rain forests are found near coasts and mountains in New Zealand, Tasmania, Japan, northern Europe, South Africa, and the Pacific Coast of the Americas. A few small temperate rain forests are found inland in places where moist winds rising into mountains drop heavy annual rainfall.

History of rain forests

Ever since land plants grew large enough to form forests, rain forests have been an important ecosystem. The first land forests appeared during the Devonian Period, about 420 million to 360 million years ago. During the Carboniferous Period, about 360 million to 300 million years ago, rain forests covered much of Earth’s land surface. Plants of these ancient rain forests differed greatly from rain forests today. Treelike club mosses and ancient horsetails dominated the forests of the Carboniferous period. Invertebrates (animals without backbones) ruled the rain forests. Many of these invertebrates grew much larger than their modern counterparts. Dragonflies with wingspreads of 28 inches (70 centimeters) or more patrolled the skies, long before the development of birds. Scorpions up to 28 inches in length served as top predators. Most land vertebrates were somewhat similar to modern amphibians.

By the late Carboniferous Period, the first cone-bearing gymnosperm plants appeared. They became important forest elements in the Permian, Triassic, and Jurassic periods, from about 300 million to 145 million years ago. Flowering plants evolved late in the Jurassic Period, about 200 million to 145 million years ago. By the Cretaceous Period, about 145 million to 65 million years ago, rain forests began to resemble their modern forms, dominated by such flowering plants as woody dicot trees and a variety of monocot families. The global climate was much warmer, and tropical rain forest vegetation covered much of Earth’s land, including North America as far north as what is now Colorado.

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, the last dinosaurs and many other species died out. Around that time, animals associated with modern rain forests began to appear. Primates became more widespread. Tapirs, sloths, and anteaters first evolved and later became more diverse. Up until the Pleistocene Epoch, about 3 million to 10,000 years ago, these groups were much more diverse than they are today. Giant ground sloths, about 20 feet (6 meters) in length, roamed the Amazon. These and other gigantic seed-eating mammals may have been important seed dispersers for trees that still exist today. Such trees have seeds too large to be dispersed through digestion by modern animals.

The movement of the continents has played a major role in the history of rain forests. Around 105 million years ago, a supercontinent (giant land mass) known as West Gondwana split into what are now Africa and South America. The two gradually moved farther and farther apart. Most modern rain forest organisms did not exist at the time. But many evolved around 50 million to 60 million years ago, when the two continents were much closer than they are today. The closeness made it easier for organisms from one continent to disperse to the other. As the continents moved farther apart, this exchange of organisms declined, resulting in some unique distinctions. For example, hummingbirds originated in South America relatively recently and are therefore not present in Africa.

A major event in rain forest history occurred much more recently and helps explain why the American rain forests are so diverse. Around 4 million years ago, moving plates lifted what is now Panama above the water, creating a bridge between the previously separate North and South America. Species that had evolved on one continent could expand their populations to the other, enriching the diversity of species in that new land. Cichlid fishes, poison frogs, parrots, hummingbirds, and modern sloths expanded northward from South America. Meanwhile, pit vipers, peccaries, and big cats migrated into South America. The interchange was probably even more dramatic among plant and insect species.

Rain forests and people

Cacao, the plant that gives us chocolate, is a small tree that grows in the rain forest understory. It is native to South America. Chili peppers, black pepper, mangoes, bananas, and passion fruit are just a few other important food plants from the rain forest. Humans domesticated (developed into crops) these plants from their rain forest ancestors. Many popular nuts, including cashews and Brazil nuts, originated in tropical rain forests.

Native cultures.

Such groups as the Yanomami of South America, the Dayaks of Southeast Asia, and the Mbuti of central Africa have lived in rain forests for centuries. They make their living by hunting, fishing, collecting forest products, and farming.

Many more cultures lived in the rain forests of Africa, Asia, and the Americas in the past. Little is known of some of these peoples, in part because the wet conditions in a rain forest speed the breakdown of artifacts, tools and other items made by people. Small native groups practiced both hunting and gathering and small-scale farming in the rain forest. Some of these cultures made use of slash-and-burn agriculture, cutting down and burning wild plants to clear and fertilize crop fields. When a crop field grew poor through years of farming, the forest was allowed to reclaim it.

A more widespread early rain forest culture was the Maya of what are now Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and Belize. The Maya had one of the most advanced cultures of their time. Their civilization spanned from about 1000 B.C. to 1697 A.D., when the Spanish conquered their last independent city. The Maya used irrigation systems to grow such crops as corn, beans, and squash on a large scale. Amazing pyramids in Petén, Palenque, and Tikal stand as reminders of their greatness.

Threats to rain forests.

Human interactions with rain forests have changed dramatically since around 1500. At that time, European settlers began to explore and expand into rain forests. They often extracted large quantities of forest products and established low-productivity agricultural systems, such as cattle ranching. Such practices have resulted in a great loss of rain forests.

Current deforestation is threatening some of the most important tropical rain forests in the world. In Indonesia, the expansion of oil palm plantations has created devastating forest loss. In the Amazon, much forest has been lost to increased soy production. In the past, agricultural deforestation was limited by the availability of human labor to work farms. However, modern soy production relies on large machines instead of human workers, and oil palm requires less human labor than traditional crops.

The rain forest could regenerate the small parcels of land cleared by traditional agriculture. But today, the combined effects of deforestation and pollution produce a much greater setback. Particularly damaging practices include oil drilling, chemical-intensive agriculture, and the use of mercury in gold mining. These practices have introduced extreme pollution to previously pristine areas, harming plants, animals, and people. Unlike the cutting of trees, from which a rain forest can recover in a few decades, the impacts of chemical pollution are much longer lasting.

Oil drilling is especially problematic in rain forests. In countries such as Ecuador and Venezuela, foreign oil companies have extracted crude oil for several decades, producing heavy pollution in the process. Historically, few measures have been taken in rain forest areas to minimize spills and other damage. In the 1970’s and 1980’s, spills and contamination were common. Such issues led to heavy contamination of rain forests and created great health problems for native populations.

The industrial scale farming of such crops as banana and pineapple also harm rain forests. Plantations of these crops can extend for thousands of acres or hectares, covering entire watersheds. Banana and pineapple plantations depend heavily on pesticides to control pests. The result is pollution of both land and waterways, affecting the entire food web.

Saving rain forests.

At the same time that rain forests are rapidly being destroyed, researchers are discovering amazing things about them. The biodiversity of rain forests may be 10 to 20 times as high as once thought. Among this wealth of life forms—if they can be saved—may be species that can improve the lives of people. The medicine quinine, for example, is made from the bark of South America’s cinchona tree. It is used to treat the disease malaria. Quinine was one of the first rain forest medicines adopted worldwide. Healers from traditional cultures have used a wide variety of other rain forest plants for centuries to treat everything from toothache to snakebite. Medicines derived from such plants may someday save or improve millions of lives.

Conservationists are developing new ways to protect rain forests ecosystems. Many of these hold great potential for reversing our damaging relationship with rain forests.

Ecotourism is an increasingly important approach to protecting rain forests. Ecotourism is environmentally and socially responsible tourism that promotes the conservation of natural areas. The income brought by visitors can help native people, serving as a healthful alternative to destructive economic activities such as deforestation and mining. Ecotourism can also provide education for visitors and increase their awareness of the beauty and importance of rain forests. National parks have been created in some areas to protect forests and serve as ecotourism destinations.

Conservationists are exploring other sustainable uses of the rain forest. As they grow, trees collect carbon in their trunks. Reforesting in the tropics is therefore an attractive means of removing excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Conservationists are also working to promote less damaging, more sustainable agriculture. Activists have called for a reduction of the impact of oil palm farming by pressuring food companies to replace palm oil in their products.