Rome, Ancient. The story of ancient Rome is a tale of how a small farming community on the bank of the Tiber River in central Italy grew to become one of the greatest empires in history, and then collapsed. According to Roman legend, the city of Rome was founded in 753 B.C. By 272 B.C., the Roman Republic controlled most of the Italian Peninsula. At its peak, in the A.D. 100’s and 200’s, the Roman Empire governed about half of Europe, much of the Middle East, and the north coast of Africa. The empire then began to crumble, partly because it was too big for Rome to govern. The empire split into two parts in A.D. 395, the West Roman Empire and the East Roman, or Byzantine, Empire. The West Roman Empire fell in A.D. 476 and was replaced by small Germanic kingdoms. The Byzantine Empire continued for centuries.

Ancient Rome had enormous influence on the development of Western civilization. Latin, the language of the ancient Romans, became the basis of French, Italian, Spanish, and the other Romance languages. Roman law provided the foundation for the legal systems of most of the countries in Western Europe and Latin America. Roman roads, bridges, and aqueducts—some of which are still used—served as models for engineers in later ages.

This article provides a broad overview of the land, people, government, way of life, arts and sciences, economy, and history of ancient Rome. Many separate World Book articles have more detailed information.

The world of ancient Rome

The land.

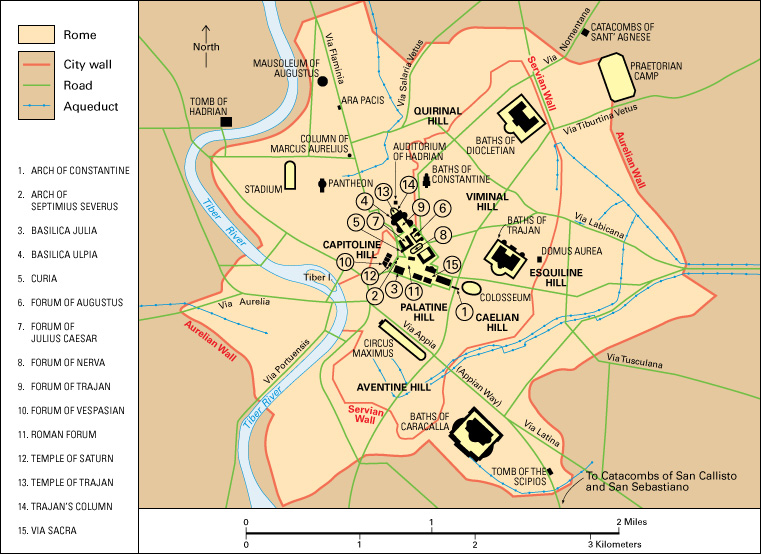

The city of Rome was founded on seven wooded hills next to the Tiber River in central Italy. The hills were steep and easily defended against enemy attacks. The valleys had fertile soil and good irrigation, as well as materials necessary for building.

As Rome grew, much of the city was built upon the swampy lowlands beneath the seven hills. These parts of Rome often suffered damaging floods from the Tiber. But the Tiber also provided a convenient route to the sea, which lay about 15 miles (24 kilometers) to the west. The harbor at Ostia, a town at the mouth of the Tiber, allowed for extensive trade with other communities.

The Italian Peninsula, which Rome controlled for much of its history, juts far into the Mediterranean Sea and occupies a central position among the Mediterranean lands. To the north, the Alps provided a natural defense against invaders from central Europe. But passes through the mountains allowed settlers, attracted by the mild climate and fertile soil, to travel into Italy.

Roman rule eventually spread over all the lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea. The Romans called the Mediterranean Mare Nostrum (Our Sea) or Mare Internum (Inland Sea). At the Roman Empire’s greatest size, in the A.D. 100’s and 200’s, the empire extended as far north as Scotland and as far east as the Persian Gulf.

The people.

When Rome was founded, a number of different tribes lived on the Italian Peninsula, each with its own language and culture. The Romans were Latins. Other major tribes included the Etruscans, Sabines, and Samnites.

The Roman Empire, at its height, had over 50 million people. In the east, Rome controlled Mesopotamia, Palestine, Egypt, and Greece. In the west, Rome conquered Britain and Gaul (now mainly France, Belgium, and part of Germany). Almost 1 million people lived in the city of Rome. Alexandria in Egypt, the empire’s second largest city, had over 500,000 inhabitants.

Latin and Greek were the official languages of the empire. Government officials and members of the upper classes spoke those two languages. But most people in the empire continued to use their native languages. Celtic was spoken in Gaul and Britain, Berber in northern Africa, and Aramaic in Syria and Palestine.

People belonged to one of three groups in ancient Rome: (1) citizens, (2) noncitizens, and (3) slaves. Roman law recognized citizens and noncitizens as free. Slaves were treated as property. Citizenship gave protection under Roman law, and only a citizen could become a senator or government official.

The citizens of Rome were further divided into different social classes. At the top were members of the Senate, who were often wealthy landowners. Next were the equites << EHK wuh teez >> , prosperous businessmen and merchants. Under the Roman emperors, equites held important government positions and assisted in the running of the empire. The majority of Roman citizens belonged to the lower classes. They were farmers, city workers, and soldiers.

At first, only those born in Rome could become citizens, so the majority of people were noncitizens. As Rome expanded, it granted citizenship to more people in the empire. The privilege of citizenship promoted loyalty to the empire and gave all classes and all regions a greater stake in its success. Women and children could become citizens, but they could not vote.

Slaves were regarded as property by Roman law, but they were essential to the Roman way of life. They performed tasks ranging from heavy labor to teaching the young nobles of Rome. Most slaves were captured in war. A wealthy Roman family might have hundreds of slaves working on its farmland and in its home. Slaves could buy their freedom from their masters, or be given it. Freed slaves, known as freedmen, owed allegiance to their former masters, who relied on them for continued service.

Government

A series of kings ruled ancient Rome at the beginning of its history. Each king was advised by a Senate made up of the heads of Rome’s leading families. Ordinary citizens had little say in the running of the state.

The Roman Republic

was established in 509 B.C., after Roman nobles overthrew the king. Under this new government, the Senate became the most powerful body. It decided foreign and financial policy and passed decrees (official orders). The senators were former magistrates (government officials) who held office for life.

To succeed politically, magistrates had to follow the cursus honorum (ladder of offices). The first step was serving as a military officer. Next, they would try to be elected as a quaestor (financial official), then as an aedile (public works official), then as a praetor (judicial official). After serving as praetor, magistrates automatically entered the Senate.

The highest position was consul. There were two consuls, elected annually, who headed the government and took command of the army in times of war. Each Roman year was named after the consuls who ruled that year.

All magistrates held office for one year. After serving in one position, they had to return to private life for a year before holding another office. As Rome expanded, praetors and consuls left the city after their year in office to govern the provinces as propraetors or proconsuls.

During the B.C. 400’s and 300’s, the landowning upper classes—the patricians—struggled for power with the other classes—the plebeians. The dispute became known as the Conflict of the Orders. Originally, only patricians could hold public office, become priests, or interpret the law. But the importance of the plebeians in fighting wars helped them gain a greater voice. The plebeians formed their own assembly, the concilium plebis, and elected leaders known as tribunes who championed their causes. By 287 B.C., plebeians had won the right to hold any public or religious office and had gained equality under the law. However, the richest families continued to control the assemblies and the Senate.

During the later republic, in the first century B.C. (100-1 B.C.), two political groups arose out of the senatorial classes. They were called the optimates and the populares. The optimates believed in the traditional power of the Senate, which they used to increase their power and get laws passed. The populares believed in the power of the people. They used the people’s tribunes and popular support to advance their political agenda.

The Roman Empire

was established in 27 B.C., after the republican government collapsed. The republican institutions of government continued, but emperors held supreme authority. They nominated the consuls and appointed new senators. The citizen assemblies had little power. Emperors headed the army and directed the making of laws. They relied more on their own advisers than on the Senate. A vast civil service handled the empire’s day-to-day business.

The law.

The Romans published their first known law code in 451 B.C. This code of law, known as the Laws of the Twelve Tables, was basic. As Rome grew, its legal system developed and became more complex. Rome became the first society with experts whose job was to interpret the law on behalf of clients—experts now called lawyers.

A general set of legal principles developed known as the jus gentium (law of nations). It was based on common-sense notions of fairness and took into account local customs and practices. Much of what we know of Roman law comes from the Theodosian Code of A.D. 438 and the Digest, law cases and interpretations compiled by the Emperor Justinian in the A.D 500’s.

The army

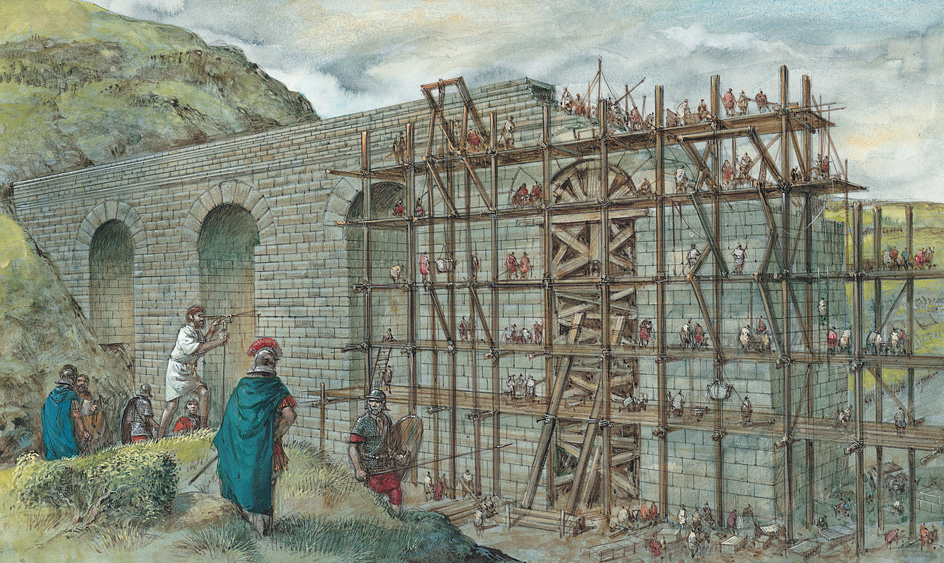

was composed of three groups: (1) the legions, (2) the auxiliaries, and (3) the Praetorian Guard. Only Roman citizens could join the legions. Each legion consisted of about 5,000 men. Besides soldiers, legions also had doctors, surveyors, and engineers. Although the chief purpose of the legions was military, legions also built roads, aqueducts, walls, and tunnels.

Noncitizens joined the auxiliaries, which fought alongside the legions. Auxiliaries were made up of specialized troops, such as archers or cavalry.

The Praetorian Guard was an elite group of soldiers who served as the emperor’s personal bodyguard. It was the only army group stationed in the city of Rome.

The normal length of military service was 25 years. Most soldiers were professionals, whose training and discipline helped to make the Roman army successful. After their term of service, many veterans and their families settled in colonies (towns made up of former soldiers). The colonies acted as models of Roman life for people in the provinces, and the former soldiers provided a ready peacekeeping or police force if trouble arose.

Way of life

City life.

Rome was the capital and largest city of the empire. Other important cities included Alexandria in Egypt, Athens in Greece, Antioch in Syria, and Byzantium (later Constantinople, now Istanbul) in Turkey.

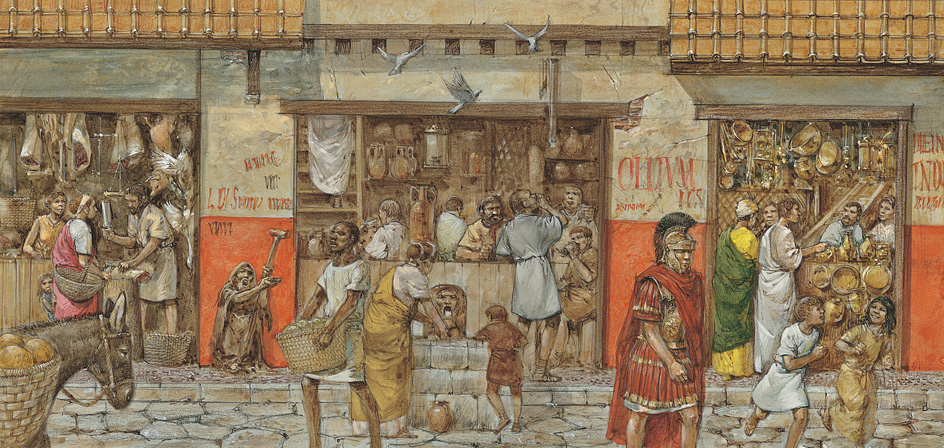

Cities in the Roman Empire served as centers of trade and culture. Roman engineers planned cities carefully. They set public buildings in central locations and provided efficient sewerage and water-supply systems. Emperors and other wealthy individuals paid for the construction of public buildings, such as baths, arenas, and theaters. At the heart of the Roman city was the forum, a large open space surrounded by markets, government buildings, and temples. It was the center for business and religious life and offered a place where everyone could mingle, rich and poor alike.

Most people in Roman cities lived in cramped apartment buildings that were three to five stories high. Many of these buildings had unsanitary conditions, and a number of them burned to the ground.

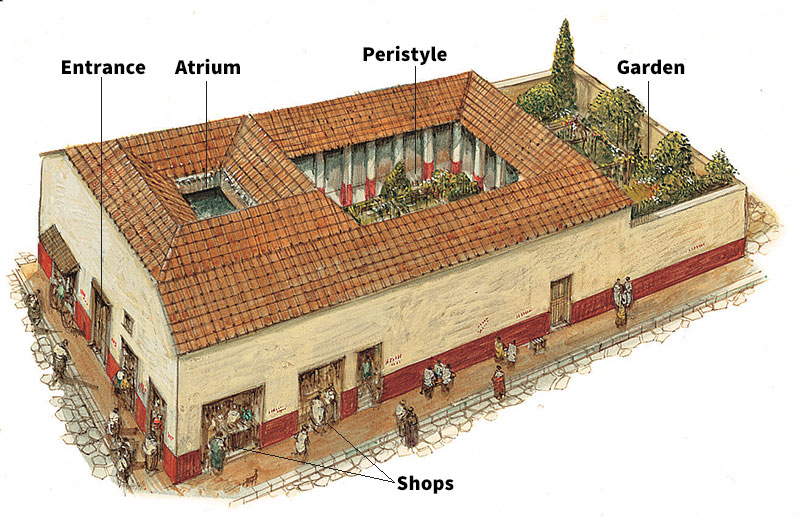

Wealthy Romans lived in houses built around two courtyards known as the atrium and the peristyle. Windowless rooms surrounded the atrium, but a roof opening let in light and air. A dining hall and other rooms circled the larger peristyle, which was also open to the sky and had a garden.

Rural life.

The first Romans were shepherds and farmers. In early Rome, landowners planted their crops in the spring and harvested them in the fall. During the summer, they would fight in the army. As Rome expanded, small farmers spent longer periods away fighting. Many were forced to sell their land to wealthier landowners. This led to the development of large estates known as latifundia, which were worked by massive teams of slaves.

For these slaves and most small landholders, rural life involved hard physical labor. The Roman calendar featured regular agricultural festivals. The games and entertainments at these festivals offered a break from the hardships of working the land.

Most rural people lived in simple dwellings made of sun-dried bricks. Wealthy landowners lived in luxurious villas, which were larger than houses in the city.

Family life.

The head of the Roman family was the paterfamilias (father of the family). Legally, he had power over his entire household, which included his wife, children (even if adults), slaves, and freedmen. As long as his father lived, a son could not own property or have legal authority over his own children. However, in practice, adult sons ruled their own families.

Girls could legally marry when they were 12 years old, and boys when they were 14. However, a man might not marry until he was in his 20’s and had already begun his career. Among the upper classes, parents arranged most marriages for the economic or political benefits that the unions would bring the families. During the republic, marriage made a woman and everything she owned her husband’s property. During the empire, the woman kept her legal rights and her own property.

Food.

Most Romans ate simple meals. Breakfast was usually a light meal of bread and sometimes cheese. Lunch and dinner consisted mainly of porridge or bread plus olives, fruit, or cheese. Garum, a sauce made of fish parts and olive oil, was a popular addition.

Wealthy Romans sometimes served dinners with several courses. The first course might include eggs, vegetables, and shellfish. The main courses featured meat, fish, or chicken. For dessert, the diners often ate honey-sweetened cakes and fruit.

Clothing.

The Romans wore simple clothes made of wool or linen. The main garment was the tunic, a gown that hung to the knees or below. On formal occasions, citizens of Rome wore a toga, which resembled a white sheet draped around the body. The togas of senators and other high-ranking citizens had a purple border. It was against the law for noncitizens to wear togas. Romans wore cloaks over their tunics or togas when the weather was cold or wet.

Women often wore a stola, a long dress with many folds. Wealthy women wore a palla, which was similar to a toga, as well as jewelry, makeup, and styled hair. Most women’s clothing was dyed in bright colors.

Recreation.

Bathhouses served as centers for daily exercise and bathing, as well as for socializing. Normally, there were separate baths for men and women. Bathhouses had a grand exercise area, the palaestra, for wrestling, boxing, or running. After exercising, the bather would be massaged by a slave, then move through rooms with warm, hot, and cold pools to cleanse and energize the body.

Much of the Roman year was devoted to religious holidays in honor of gods and goddesses. During the republic, there were almost 60 of these special days. By the A.D. 100’s, there were 135 each year.

Many religious holidays were celebrated with free public entertainment. Occasionally, the emperor or wealthy state officials sponsored productions in circular arenas known as amphitheaters. The most famous amphitheater, the Colosseum in Rome, could seat about 50,000 spectators. Here, trained fighters known as gladiators fought each other to the death. Most gladiators were slaves or condemned criminals, but some citizens gave up their freedom to become gladiators. Successful gladiators were admired, much as modern athletes are, but most gladiators died brutal deaths. In other events, armed men fought exotic wild animals, or beasts attacked condemned criminals or Christians.

Chariot racing was a popular spectator sport. In Rome, charioteers raced in a long, oval arena known as the Circus Maximus, which could seat more than 250,000 people. Charioteers raced for one of four teams—red, green, blue, or white. Like modern sports teams, each team had loyal fans. Success as a charioteer brought fame and fortune.

Theaters in Rome staged comedies and tragedies by Greek and Roman authors. More popular, however, were mimes (short plays about everyday life) or pantomimes (stories told through music and dancing).

Religion.

The Romans adopted most of their gods from the Greeks, giving them Roman names. For example, Jupiter, the supreme god, was the Roman name for the Greek god Zeus. The Romans erected temples and shrines to honor their gods. The centerpiece of every Roman city was a temple to the three divine beings called the Capitoline triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

Rulers of Rome were sometimes designated as gods. Romulus became the god Quirinus, and some emperors, including Augustus, Claudius, and Vespasian, were deified (made gods) after their death. Late in the empire, people began worshiping emperors as gods while they were still alive.

The Roman state controlled religion. Priests were government officials, elected or appointed to office. They performed sacrifices and other ceremonies to win the favor of the gods for the state. The most important priests were the pontifices. The chief priest was known as the pontifex maximus. During the empire, this position was always held by the emperor.

An important feature of Roman religion was divination—telling the future and examining the will of the gods to ward off their anger. Priests known as augurs looked for signs in the flight of birds. The Sibylline Books, a set of religious texts, offered remedies to deal with portents (natural occurrences interpreted as signs) such as earthquakes or sudden storms. Individuals used other types of divination, such as astrology.

As Roman religion became more political, people turned to other kinds of religious worship. Many practiced religions that promised salvation and happiness after death. Christianity became a popular alternative to Roman religion. The Roman government saw Christianity as a threat and persecuted its followers. But by the A.D. 300’s, Christianity had become the main religion of the empire.

Education.

Most children received their earliest education at home under the supervision of their parents. In wealthy homes, slaves taught the children. These slaves were often well-educated men from Greece. From the age of 6 or 7 until 10 or 11, most boys and some girls attended a private school or studied at home. They learned reading, writing, and mathematics. Most Roman children who received further education came from wealthy families. From the age of 11 until about 14, they studied mainly Latin and Greek grammar and literature, as well as mathematics, music, and astronomy.

Higher education focused on the study of rhetoric—the art of public speaking. Upper-class Romans prized the ability to argue persuasively before the law courts or to debate effectively in the Senate. To improve their abilities as public speakers, students might also read philosophy and history. Few women got higher education.

Arts and sciences

Architecture and engineering.

The ancient Romans adopted the basic forms of Greek architecture. For example, Roman temples were surrounded by columns with a covered portico (walkway), just as those in Greece. But the Romans generally built grander and more extravagant buildings than the Greeks.

Two achievements of Roman engineering made larger buildings possible: the arch and concrete. Arches supported such structures as bridges and the aqueducts that carried water to Roman cities. Arched roofs known as vaults spanned the interior of buildings. Vaults eliminated the need for columns to hold up the roof and so created more open floor space. Although the Romans did not invent the arch, they made better use of arches than previous cultures.

The Romans developed concrete, which served as a strong building material for walls, vaults, and domed buildings. The most famous Roman building made with concrete is the Pantheon in Rome, which has a concrete dome about 142 feet (43 meters) in diameter.

Sculpture, painting, and mosaics.

Roman sculptors also illustrated historical events through carvings on large public monuments. For example, the richly decorated Ara Pacis (Altar of Peace) celebrated the peace brought to the empire by the Emperor Augustus. Carvings on columns and triumphal arches celebrated the emperor and Rome.

Wallpaintings decorated the houses of the wealthy. Paintings often showed garden landscapes, events from Greek and Roman mythology, historical scenes, or scenes of everyday life. Romans decorated floors with mosaics—pictures or designs created with small colored tiles. The richly colored paintings and mosaics helped to make rooms in Roman houses seem larger and brighter and showed off the wealth of the owner.

Literature.

The annual change of leadership in republican government gave rise to Rome’s own particular form of history, the annals (year-by-year narratives). Livy wrote the annals of the history of the Roman people, and Tacitus adapted the form in his account of the first emperors of Rome. Other important literary works include the letters, speeches, and philosophical writings of Cicero; the satires (mocking poetry) of Horace and Juvenal; and the letters of Pliny the Younger.

Science.

The ancient Romans made few scientific discoveries. Yet the work of Greek scientists flourished under Roman rule. The Greek geographer Strabo traveled widely and wrote careful descriptions of what he saw. Alexandria in Egypt became an important center for scientific study. There, Ptolemy developed a system of astronomy that was accepted for nearly 1,400 years. Galen, a Greek physician, proposed important medical theories based on scientific experiments. The Romans themselves gathered important collections of scientific information. For example, Pliny the Elder gathered the scientific knowledge of his day in a 37-volume encyclopedia.

Economy

Rome profited from the economic resources of the regions and nations it conquered. Its vast wealth funded the magnificent buildings and art that decorated Rome and other imperial cities. Roman riches also financed roads, aqueducts, and other public works projects.

Agriculture.

Most of the people in the Roman world lived by farming. Roman farmers understood the need to rotate crops to maintain the fertility of the soil for future seasons. Farmers who could afford to would leave half of every field unplanted.

In fertile valleys north and south of Rome, farmers grew wheat, rye, and barley. Olives and grape vines flourished on rockier hillsides. Shepherds grazed sheep and goats, and other farmers raised hogs, cattle, and poultry. As the empire expanded, farms in Gaul, Spain, and northern Africa supplied Rome with many agricultural products. In Africa, local farmers grew rich from their export of olive oil, which was used both for cooking and as a lamp fuel.

Mining.

After agriculture, mining was Rome’s most important industry. The great building projects in Rome and in other cities throughout the empire required huge quantities of marble and other materials. Greece and northern Italy provided much of the marble. Italy also had rich deposits of copper and iron ore. Gold and silver were mined in Spain and Britain. Britain also produced iron for weapons and armor, lead for water pipes, and tin, much of which was used to produce bronze. Slaves, condemned criminals, and prisoners of war worked in the mines. The miners labored in cramped and unsanitary conditions, chained together.

Manufacturing

industries were small compared to agriculture and mining. The city of Rome imported most of its manufactured goods from other Italian communities. They supplied Rome with such products as pottery, glassware, weapons, tools, and textiles.

Trade

thrived as the empire expanded. Trade routes crossed land and sea, both within the empire and beyond its borders. Ships moved goods faster than the slow-moving carts used to carry merchandise over Roman roads. But both ships and carts had to guard against foul weather, pirates or highway robbers, and spoilage.

Rome imported foods, raw materials, and manufactured goods from within the empire. Rome also imported silk from China, spices and precious gems from India, and ivory and wild animals from Africa. Italy’s leading exports were wine and olive oil.

The government issued coins of gold, silver, copper, and bronze from Rome. Local government centers, such as London in Britain (which the Romans called Londinium) or Lyon in Gaul (called Lugdunum), also issued coins. The central regulation of weights and measures for coinage made trade throughout the empire easier.

Transportation and communication.

Rome had a highly developed postal system that could bring a letter from the most distant outpost of the empire to Rome. Postal stations stood on main roads throughout the empire. The emperor maintained regular contact with governors in the provinces by letter.

The Romans had a huge fleet of cargo ships, which traveled to ports on the Mediterranean Sea and carried goods up and down the Rhine, Danube, and Nile rivers. Permanent navies in the Mediterranean Sea and the English Channel protected trade ships from pirates.

In Rome, a government newsletter called Acta Diurna (Daily Events) was posted throughout the city. The paper recorded important social and political news. Officials inscribed important decrees and notices on stone or bronze and posted them prominently in major cities.

History

The regal period.

Little is known about the early days of ancient Rome. Archaeologists have found the remains of houses that were built around 900 B.C. on the Palatine Hill. The earliest settlers were a people called the Latins. They inhabited many neighboring towns in Latium, the region around Rome.

According to legend, Rome was founded in 753 B.C. by twin brothers, Romulus and Remus. A dispute between the brothers led to the death of Remus, and Romulus named the city for himself. After Romulus, six more kings governed Rome. Each contributed to the development of the new state in a unique way. For example, the second king, Numa, introduced religious ceremonies to Rome. The heads of leading noble families made up the Senate, which advised the king.

About 600 B.C., Rome and other towns in Latium came under the control of the Etruscans, who lived in northern Italy. The Etruscans, the most advanced civilization in Italy, built roads, temples, and other public buildings in Rome. Trade increased during this period, and with it, so did Rome’s prosperity. The last king was an Etruscan named Tarquin the Proud. He ruled so harshly that the Roman nobles expelled him and created a new form of government called a republic, without a single, all-powerful ruler.

The republican period.

In 493 B.C., Rome entered into an alliance with the Latin League, a union of the cities of Latium. By 396 B.C., Rome was the largest city in the region and used the league’s resources to fight its neighbors. When Rome conquered a city, it offered protection and certain privileges, such as special trading rights. In return, the conquered cities supplied the Roman army with soldiers.

From the 300’s to mid-200’s B.C., Rome won victories over the Etruscans. In 338 B.C., Rome overpowered and disbanded the Latin League. In 290 B.C., the Romans conquered the Samnites, a mountain people who lived south of Rome. In the 200’s and 100’s B.C., Rome defeated the Gauls, who had invaded Italy from the north and burned Rome in 390 B.C. After a victory over the Greek colony of Tarentum in southern Italy in 272 B.C., Rome ruled most of the Italian Peninsula.

After the Second Punic War, Rome began to expand in the east toward Greece and Macedonia. In 146 B.C., the same year as the destruction of Carthage, Rome burned Corinth to the ground and took control of Greece. Soon after, King Attalus III of Pergamum died and left his kingdom to Rome, which became a wealthy province the Romans called Asia (now part of Turkey).

The later years of the republic.

Acquiring territories abroad led to discontent at home. Military campaigns took longer and longer, and poverty-stricken farmers often returned to find their lands ruined. But the wealthy profited from the slaves and goods captured in the fighting and from business opportunities in the new lands. The gap between rich and poor widened, but Rome’s wealthiest citizens opposed attempts to narrow it. In the 100’s B.C., the tribune Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and his brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus, attempted a program of reform, including giving public land to the poor. But opponents killed them and halted their reforms.

The Roman general Gaius Marius then came to power. Marius served as consul seven times from 107 to 86 B.C. He used tribunes to win popular support and to gain political power. He also reformed the army, offering rewards to his men for successful campaigns. From 91 to 89 B.C., Rome fought with its Latin allies, who wanted to be awarded citizenship in return for assisting Rome abroad.

Civil war broke out in the 80’s B.C. between Marius and another general, Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Marius died in 86 B.C., and Sulla eventually triumphed over Marius’s followers. Sulla declared himself dictator in 82 B.C. and reorganized the state. He enlarged the Senate, reduced the powers of the tribunes, and took measures to prevent corruption in the provinces. In 79 B.C., Sulla stepped down as dictator and retired from politics.

Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus, allies of Sulla, became the next leading generals. In 67 B.C., Pompey rid the Mediterranean of the pirates who had plagued Roman trade. He then conquered eastern Asia Minor (now Turkey), Syria, and Judea (now mostly Israel). Crassus put down the slave rebellion led by Spartacus. But the Senate blocked the rewards that Pompey and Crassus sought for their achievements. In 60 B.C., Pompey and Crassus joined Gaius Julius Caesar to form an unofficial political alliance known as the First Triumvirate. They arranged Caesar’s election as consul in 59 B.C.

From 58 to 51 B.C., Julius Caesar conquered Gaul. Pompey stayed in Rome and gained political power. Crassus took an eastern command but was killed fighting the Parthian Empire, based in what is now Iran. Caesar and Pompey then saw each other as rivals for control of the empire. In 49 B.C., Caesar returned to Italy, and another civil war began. Over the next few years, Caesar defeated Pompey and his supporters. By 45 B.C., Caesar had become sole ruler of the Roman world. But many powerful Romans distrusted him, and in 44 B.C. a group of aristocrats assassinated him.

More civil war followed Caesar’s death. In 43 B.C., Caesar’s adopted son and heir, Octavian, formed the Second Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, the pontifex maximus (chief priest). They took revenge on Caesar’s assassins and dealt violently with any opposition. Mark Antony and Octavian eventually pushed aside Lepidus and fought each other for control of the empire. Antony sought the support of Cleopatra, queen of Egypt. The two became lovers and had children together. In 31 B.C., Octavian defeated them in the Battle of Actium off the west coast of Greece. The next year, Egypt became a Roman province.

Imperial Rome.

After the defeat of Antony, Octavian was the unchallenged leader of the Roman world. In 27 B.C., he became the first Roman emperor and took the name Augustus (Revered One), a word that held religious meaning. More than a century of internal upheavals and civil war, caused by the ambitions of powerful individuals, had destroyed the republic. Only a strong individual who had the support of the army, the Senate, and the people would be able to govern the Roman world.

The reign of Augustus marked the beginning of a period of stability known as the Pax Romana (Roman Peace), which lasted until about A.D. 180. Augustus reestablished an orderly government in which the traditional republican forms of government—Senate, consuls, tribunes—still functioned. But Augustus had supreme power. He commanded the army and controlled the most important provinces. He nominated the consuls and appointed new senators. Citizen assemblies had little power, but he kept the masses happy through entertainment and handouts of free grain and money.

The emperor relied heavily on loyal advisers and established a personal bodyguard, the Praetorian Guard, which was stationed in Rome. Augustus established strong defenses along the frontiers of the Roman Empire and kept the provinces under control. He began to develop a civil service staffed by skilled administrators to govern the empire more effectively. During what came to be known as the Age of Augustus, Roman trade, art, and literature flourished.

Augustus died in A.D. 14 and was succeeded by his stepson Tiberius. Tiberius and the other relatives of Augustus who ruled after him were known as the Julio-Claudians. They ruled Rome until 68. In the Year of the Four Emperors in 69, four generals stationed around the empire made claims to the throne. The governor of Judea, Vespasian, emerged victorious. He and his two sons, Titus and Domitian, were known as the Flavians. They ruled until 96. Domitian ruled with excessive cruelty, but a kindly emperor named Nerva succeeded him and brought an age of peace and prosperity. The Antonine rulers—from Nerva to Marcus Aurelius—were noted for their wisdom and ability.

Augustus had left strict instructions to his successors not to expand the empire. However, Claudius invaded Britain in 43. In northwestern Africa, Claudius added a region called Mauretania (now northern Morocco and western Algeria) to the empire. Trajan seized Dacia in eastern Europe in 106. Hadrian returned to the policy of Augustus. He marked the limits of Rome’s empire with artificial frontiers on the Danube River, in northern Africa, and elsewhere. In northern England, he constructed Hadrian’s Wall, parts of which still stand.

The expansion of the empire gave wealthy Romans new opportunities for investment. Both small farms and large estates thrived. Roman roads, built initially to speed troop movements, made trade and communication easier. The Romans erected imposing towns and cities, even in such remote areas as Wales, Scotland, and Mauretania. The equites controlled the civil service, which became increasingly skilled at running the day-to-day business of the empire.

The decline of the empire.

As time went on, the power of the emperors increased and the people became less politically active. The Roman Empire’s enormous size hastened its decline. One man in Rome could no longer hold the empire together. The far-flung armies on Rome’s borders were often more loyal to their commanders than to the emperor. Enemies of Rome, such as the Goths in central Europe and the Parthians in southwest Asia, mounted serious attacks.

In 161, Marcus Aurelius became emperor and defended the Roman Empire against attacks by Germanic tribes from the north and Parthians from the east. His son Commodus succeeded him in 180 but was killed in 192. Many rivals tried to claim the empire, and several emperors seized power by force. From 235 to 284, there were 19 different emperors, many of them army commanders whose troops named them emperor.

Diocletian, a Roman military officer, was proclaimed emperor in 284. Diocletian attempted to stabilize the empire by reorganizing the way it was governed. He divided the provinces into smaller units and gave each its own government and army. Diocletian established a tetrarchy (rule of four). Under this system, Diocletian ruled the eastern part of the empire and a co-emperor, Maximian, ruled the west. In addition, two Caesars (junior emperors), Galerius and Constantius, ruled under Diocletian and Maximian. Diocletian tried unsuccessfully to aid Rome’s economy by standardizing coinage and imposing price controls. He also persecuted followers of Christianity and other religions.

After Diocletian retired in 305, several men struggled to gain power, and the tetrarchy failed. Eventually, Constantine I, who had been a deputy of Diocletian, came to power. He once again united the empire and, in 313 through the Edict of Milan, granted Christians freedom of worship. In 325, at the Council of Nicaea, Constantine recognized Christianity as the chief religion of the Roman Empire. In 330, the emperor established a new capital at Byzantium and renamed it Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey).

The West Roman Empire steadily weakened. A Germanic people called the Vandals invaded Spain and later occupied northern Africa. The Visigoths, another Germanic group, invaded and looted the city of Rome under their leader Alaric in 410. In Britain, local peoples known as the Picts, Scots, and Saxons attacked the Roman troops. The emperor Honorius finally gave up Britain so he could use the troops elsewhere in the empire. A Vandal leader named Gaiseric (or Genseric) plundered the city of Rome again in 455. The empire’s final collapse came in 476, when the German leader Odoacer forced the last emperor from the seat of power. Ironically, Rome’s last emperor was named Romulus Augustulus, after the founder of Rome and its first emperor.

The East Roman Empire survived and thrived as the Byzantine Empire. Its people continued to call themselves Romans. The Byzantine Empire lasted until 1453, when the Ottomans captured Constantinople and made it the capital of the Ottoman Empire.

The legacy of ancient Rome

The Roman heritage.

Ancient Rome had a tremendous impact on the modern world. During the Middle Ages, which lasted from about the A.D. 400’s through the 1400’s, the Roman Catholic Church replaced the Roman Empire as the unifying force in Europe. It used the Latin language and preserved the classics of Latin literature.

Latin remained the language of learned Europeans for over a thousand years after the fall of the West Roman Empire. The French, Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese languages developed from forms of Latin spoken in different parts of the Roman Empire. Many words in English come from Latin.

Roman law provided a model for the legal systems of many countries in Europe, Latin America, and South Africa. Many modern governments reflect the influence of the Roman political system. For example, the Senate of the United States government gets its name from Rome’s governing body.

Roman engineering feats served as models for later engineers. Some of the roads, bridges, and aqueducts built by the Romans are still used today. The Romans demonstrated the importance of swift and reliable communication, both in war and peace.

Learning about ancient Rome.

Most of our knowledge of ancient Rome comes from documents written by the Romans themselves. These records include masterpieces of Latin literature, such as the letters and speeches of Cicero or the letters of Pliny the Younger. The Roman historian Livy told of Rome’s development from 753 B.C. to his own time, the age of Augustus. Tacitus described the period of Roman history from the reign of Tiberius to that of Domitian. Suetonius Tranquillus wrote biographies of Roman rulers from Julius Caesar to Domitian. Leading generals wrote autobiographies that detailed their achievements. For example, Julius Caesar described his conquest of Gaul in his Commentaries on the Gallic War. Other types of written records include epigraphic records (documents engraved in stone), such as law codes, treaties, and decrees of the Roman Senate and the emperors.

Scholars also derive information from scenes carved on monuments in Roman times. Generals and emperors erected these monuments to celebrate victories and other important events. For example, Trajan’s Column and the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome tell us much about the military campaigns of these leaders.

The remains of Roman towns and cities and other archaeological evidence also provide valuable information. In particular, the excavations at the towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, buried when Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79, have revealed enormous amounts of detail regarding everyday life in Roman times.

Interest in the study of ancient Rome reawakened during the Renaissance, the great cultural movement that swept across Europe from the early 1300’s to about 1600. The Renaissance began in Italy when scholars rediscovered the works of ancient Greek and Roman authors. The first major history of Rome in modern times was the British scholar Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776-1788). By the 1800’s, the study of Rome and its language was considered an essential element of a young person’s education. The German historian Theodor Mommsen, one of the great modern scholars of ancient Rome, wrote the influential History of Rome (1854-1856). Scholars of the 1900’s and 2000’s have benefited from new archaeological discoveries and modern approaches to the study of language and literature. They continue to produce many books annually on the history, politics, culture, and language of ancient Rome.