Russian literature includes some of the greatest masterpieces ever written. Russian authors have written in all literary genres (forms), but they are best known outside Russia for their novels and poetry. Style, content, and keen character analysis are central to Russian writing. The most famous Russian works show a deep concern for moral, religious, and philosophical problems.

History has had a large influence on Russian literature. Many historians believe the name Russia comes from a people called the Rus. The East Slavic lands that modern historians call Kievan Rus accepted Christianity during the late 900’s. Kievan Rus was a state made up of a number of principalities (regions ruled by a prince). Its main city was Kyiv (historically also spelled Kiev), now the capital of Ukraine. Christianity brought with it literacy that led to a literature consisting mostly of religious works.

The Tatar (Mongol) invasion and conquest dominated Russian literature from the 1200’s to the late 1400’s. But by the end of the 1600’s, translations and imitations of Western European works were appearing in Russia. By the late 1700’s, literature included expressions of social protest against the czars (emperors), serfdom, and moral and political corruption.

Much great Russian poetry, prose, and drama was written during the 1800’s. The mid-1800’s were the age of Realism in Russian literature. Beginning in the 1890’s, an artistic and cultural revival known as the Silver Age took shape. It developed from a combination of Russian religious philosophy, the ideas of German philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche, and artistic doctrines and poetry from France and elsewhere. The first 20 years of the 1900’s were dominated by poetry.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, literary activity was controlled by the Communist government. In 1922, the Soviet Union was formed, and it lasted until 1991. Socialist Realism, enforced by government censors and literary bureaucrats, required that literature portray Soviet society as full of optimism and joy. Writers who strayed from this script faced the threat of severe punishment. Under dictator Joseph Stalin many writers were arrested and killed. However, the constant struggle of Soviet writers against censorship also led to periods of creative freedom and experimentation. Since 1991, Russian literature has developed in many new directions, reflecting new patterns of post-socialist society.

Early literature

Religious literature.

The first documents written in Kievan Rus appeared around the time of the Slavic state’s conversion to Christianity, about A.D. 988. This literature, like the new religion, came from the Byzantine Empire and the Slavic kingdoms in the Balkans (an area that covers a peninsula in the southeast corner of what is now Europe). These writings were largely religious, in the form of sermons, hymns, and biographies of saints. Many of these works display imagination and vivid details of everyday life. Some works were original, but many more were based on Greek writings. Greek was the common language of the Byzantine Empire. Some saints’ lives (biographical and devotional writings about saints) continued to influence later literary works in Russia.

Early Russian literature was written in a mixture of Old Russian (also called Old East Slavic), from which modern Russian developed, and Old Church Slavonic, a related language. Old Church Slavonic came from the Slavic peoples of the Balkans after they accepted Christianity. The East Slavs could understand the new written language without much difficulty. Old Church Slavonic became the official language of the Russian Orthodox Church. This language contributed stylistic elements that are still used even in nonreligious literature to give it a more dignified tone.

Most of the literary works were both written and read by monks and clergymen. Until 1564, when the first books were printed in Russia, monks or government scribes copied all manuscripts by hand.

Nonreligious literature.

The chronicles, which were records of outstanding events, were probably the most important early nonreligious Russian writings. The capital of each principality had its own chronicle. In the 1100’s, the Grand Prince of Kyiv had some of these chronicles combined into what is now known as The Primary Chronicle. Later chronicles, particularly those of Moscow, claimed that their principalities had the right to reunite and rule all Russia. Along with dry narrative, some accounts were vivid descriptions of military or political battles. Others were fantastic stories based on legend rather than fact.

The greatest work of Old Russian literature was “The Lay of Igor’s Campaign,” written by an anonymous author of the late 1100’s. This epic prose poem, famous for its vivid imagery and nature symbolism, describes the defeat of the Kievan Rus Prince Igor by the Polovtsians, a Turkic tribe, in 1185. The work pleads for cooperation among the princes to prevent a foreign invasion. It warns that squabbles among the princes will lead to destruction. The poem proved to be a prophecy. The Tatars invaded the East Slavic lands in 1223 and 1237. By 1240, they controlled most of Kievan Rus.

Literature from the Tatar period showed less original thought than the literature of any other period in Russian history. Tatar rule, which lasted until 1480, was the dominant theme of the small amount of writing that was preserved. The “Zadonshchina” (“The Battle Beyond the Don”), an important work of the 1400’s, describes a major Russian victory over the Tatars. It has much Christian imagery and echoes of the language and imagery of “The Lay of Igor’s Campaign.”

Muscovite literature developed as the principality of Moscow rose to power after 1480. All Russian-speaking territories were gradually united into a single state under the Grand Prince of Moscow. Eventually, the Prince of Moscow became known as the czar (from Caesar, as pronounced in Byzantine Greek). Muscovite literature stressed Moscow’s right to rule the Russian lands and the czar’s absolute authority. The most remarkable stylistic development of the Muscovite period is called word-weaving. Word-weaving is based on elaborate rhetorical repetitions and emphasizes style rather than content. This style was introduced by Orthodox monks who fled to Moscow after the fall of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, in 1453.

Beginnings of modern literature

Western influences.

The 1600’s saw a significant reshaping of Russian literature. Western Europe, from which Russia had been isolated since the early 1200’s, when the country came under Mongol rule, began to influence Russian writing. Western works, such as anecdotes, fables, moral tales, poetry, and stories of knights, were translated and imitated. For the first time, rhymed verse appeared in Russia. Russian folklore was translated into written fairy tales, satires (writings that ridiculed persons or their actions), and other works. Some authors discarded Old Church Slavonic, the old literary language, and wrote in a language that was already recognizably Russian.

The most outstanding writer of the new literature was Avvakum, a conservative clergyman who belonged to the Old Believers. This group opposed changes made in the ritual of the Russian Orthodox Church in the 1650’s, which led to a split in the church. Avvakum’s autobiography reveals his colorful personality and strong religious convictions. His expressive language and striking descriptions of daily life make his writings some of the most revealing works of this period, surprisingly fresh in their style even today.

Simeon Polotsky, a monk who received a Western education in Kyiv, was a prominent author of the 1600’s. His most important contribution to literature was the introduction of a rigid syllabic system, drawn from Polish poetry, to Russian verse. Each line has a fixed number of syllables with regularly placed pauses. Polotsky wrote quaint but serious verse. Many of his works praise the czar and the ruling family. He also wrote several plays on Biblical subjects.

Czar Peter I, the Great, whose rule began in 1682, Westernized Russia and officially declared himself emperor. His adoption of Western culture and institutions led to great changes in Russian literature. Peter encouraged the translation of many European works and sent people abroad to study Western life. He also invited large numbers of Europeans to Russia. European historians, architects, musicians, dancers, and writers came to Russia during and after Peter’s rule. Many settled down to raise families in Russia.

Russian literature was completely Westernized during the 1700’s, with French, German, and English works influencing Russian authors. Antioch Kantemir, a leading poet and diplomat, wrote nine satires in syllabic verse supporting Peter the Great’s reforms and the spread of Western culture. Kantemir used everyday speech in his works, and the informal language helped his characters appear lively and typical. He also wrote in Romanian.

Mikhail Lomonosov has been called the founder of modern Russian literature and the forerunner of Russian Classicism. His dignified odes (lyric poems) praise the czar and the greatness of God. Lomonosov introduced a new type of poetry more suitable to the Russian language. Older poetic forms had been based on Greek and Latin verse. Called syllabo-tonic verse, Lomonosov’s verse features a regular pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. He also established a system of three literary styles. These styles varied among (1) the highest, or most dignified, language, full of Old Church Slavonic elements; (2) the middle language, based on spoken Russian, but without conversational expressions; and (3) the lowest, or most popular, speech. According to Lomonosov, the highest style was most suited for tragedies and odes; the middle style, for drama and satire; and the lowest, for fables or comedies. Lomonosov was also a scientist, and some of his poems are on scientific topics.

The Classical movement,

sparked by Lomonosov’s literary reforms, emerged fully in Russia by the 1740’s. Classicism came to Russia as part of the continual cultural flow from Western Europe. It provided strict rules for composition, style, and subject matter. These guidelines were inspired by models of ancient Greek and Roman literature and influenced by the literary criticism in The Art of Poetry (1674) by the French literary critic Nicolas Boileau-Despreaux.

The most typical Russian Classicist was Alexander Sumarokov. His works included fables, plays, satires, and songs. Sumarokov drew on episodes from Russian history, found in old chronicles, for some of his plays.

Vasili Ivanovich Maykov, one of Sumarokov’s followers, wrote the mock epic poem Elisey, or Bacchus Infuriated (1771). This more realistic work describes the adventures of a drunken coachman. Another important Classicist, Denis Fonvizin, became famous for his satirical comedies. The Adolescent (1782) is considered his finest work and is still widely read today. The play attacks the ignorance and cruelty of country landowners. Fonvizin was forced out of literature in the 1780’s after Empress Catherine the Great prohibited him from publishing.

The outstanding poet of the 1700’s was Gavriil Derzhavin who, like Lomonosov, was famous for his odes. In “Ode to Felitsa” (1783) and other poems, Derzhavin praised Catherine and ridiculed the vices of her courtiers. In his hands, the ode became a fresh expression of life and feeling. His work marked the turning point in Russian literature from Classical to Romantic writing.

During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, fables were a very popular form of literature. Russia’s greatest writer of fables was Ivan Krylov. His works, which used everyday Russian language and humorous characterizations, ridiculed ignorance and vanity. Some of his fables were translations of French writer Jean de La Fontaine, though Krylov wrote original fables, too.

The age of Romanticism

Romanticism, which spread to Russia from Germany and England, stressed the full expression of emotions in literature. The movement developed as a revolt against the logic and formality of Classical writers. Romantic characteristics began to appear in Russian literature during the late 1700’s. But Romanticism did not become a significant influence until the early 1800’s.

Sentimentalism,

a strong early Romantic trend, came to Russia from Western Europe in the 1790’s. Followers of this movement emphasized the importance of feelings and imagination but continued to use Classical forms in poetry. The leading Russian sentimentalist was Nikolay Karamzin. His Letters of a Russian Traveler (written in 1789 and 1790) is filled with the excitement of a young man’s trip to the West and his meetings with famous writers. “Poor Liza” (1792) is a popular tale about a peasant girl abandoned by her upper-class lover. Karamzin’s writing style shifted from the strict division of style into three levels toward a single conversational “middle style,” influenced by the French language. His History of the Russian State (1816-1829) was a fundamental work of Russian historical scholarship that is still important.

Preromanticism.

Another group of writers of the early 1800’s could be described as Preromantics. They showed a greater interest in nature than previous writers did and paid more attention to mood. Leading Preromantic writers included Vasili Zhukovsky and Konstantin Batyushkov. Zhukovsky, a gifted poet, translated works by several German and English Romantics. Batyushkov was famous primarily for his elegies (sad poems on love and death). He also wrote passionate lyrics (short poems).

Early Romanticism.

A new generation of poets appeared during the 1820’s, as the Golden Age of Russian poetry began. These poets also combined Classical forms with Romantic sentiments. However, the early Romantics showed a greater concern for individual freedom and were interested in a broader range of subjects. The poets of the Golden Age were strongly influenced by two English authors, William Shakespeare and Lord Byron.

Russia’s best-loved poet was (and still is) Alexander Pushkin, the leading writer of early Romanticism. His poems are distinguished by their economical but very expressive language. Pushkin’s concise style makes his works difficult to translate, or to appreciate in any language except Russian. Pushkin’s narrative poems deal with the place of human beings in society. Many of his main characters, such as the title hero of Eugene Onegin (1825-1832), are unable to find a purpose in life. They end up bored and indifferent to love.

In 1825, Pushkin wrote Boris Godunov, a historical drama in blank verse. He hoped to introduce Shakespeare’s type of historical play into Russian drama. “The Bronze Horseman” (written in 1833), one of Pushkin’s greatest narrative poems, centers on Peter the Great’s Westernization of Russia and its effect on ordinary Russians. The work tells of both the glorious and tragic consequences of his grand design for Russia.

Pushkin’s novel The Captain’s Daughter (1836) resembles the historical novels of Sir Walter Scott, a Scottish Romantic. One of Pushkin’s best stories, “The Queen of Spades” (1834), is about a gambler who goes mad after failing to win a fortune at cards.

Other poets of the Golden Age included Yevgeny Baratynsky, Baron Anton Delvig, and Wilhelm Kuchelbecker. Baratynsky became famous for his precise, original style. His narrative poems include Eda (1825), The Ball (1828), and The Gypsy Girl (1842).

Another important writer of the 1820’s was Alexander Griboyedov. His most famous work, Woe from Wit (1825), is a satirical comedy in rhymed verse. The hero, Chatsky, like Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, is unable to fit in with the society of his time. Onegin and Chatsky became known as superfluous (unnecessary) men whose weak natures prevented them from pursuing constructive goals. Later writers used this character type to describe Russian nobles who could not provide strong leadership in support of political and social reforms. The superfluous man often appeared as a character in Russian literature during the 1800’s and early 1900’s.

Late Romanticism

featured a new freedom of form and style and a focus on human feelings and passions. In the 1830’s, this movement also stressed the deep significance of dreams, visions, and fantasies. Some Late Romantic Russian literature addressed political and moral corruption. However, censorship had become severe under Czar Nicholas I, whose rule began in 1825. There was strict censorship of all literary works that criticized Russian society, especially the institution of serfdom.

Mikhail Lermontov was an outstanding poet and novelist. His lyrics expressed intense frustration and boredom with life in Russia. In several of his poems, Lermontov’s speakers dream of an unattainable paradise. Pride and unrestrained desire cause the hero of The Demon (written about 1839) to lose this ideal state. Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Times (1840) was the first psychological novel in Russian literature. Its hero, Pechorin, is another superfluous man. He wastes his life in senseless adventures because the strictness of Russian social and political life keeps him from any useful activities except his military duties.

Fyodor Tyutchev, a brilliant Romantic poet, wrote on such philosophical themes as the place of human beings in the universe, the limits of their understanding of nature, and the difficulty of communicating through language. His poems include “Silentium” (1830), “A Dream at Sea” (1833), and “Nature Is Not What You Think” (1836). The Late Romantic poet Karolina Pavlova wrote both verse and incisive prose that analyzed the habits of Russian society. Her short novel The Double Life (1846) uses an innovative combination of prose and poetry.

Nikolai Gogol was one of Russia’s greatest writers. His early works give colorful and often folkloric descriptions of life in Ukraine, where he was born. Taras Bulba (1835), a historical novel, praises the past glory of Ukrainian Cossacks (elite cavalry warriors). Literary critics regarded many of Gogol’s later works as political satires, but his main objective was to make fun of humanity’s spiritual weaknesses. The characters in his play The Inspector-General (1836) represent common vices. “The Overcoat” (1842), the story of a pathetic copy clerk, protests the spiritual poverty of human beings. The novel Dead Souls (1842), though never completed, is one of Gogol’s most brilliant satires. The hero, Chichikov, travels around Russia buying up titles (deeds of ownership) to dead serfs whose names are still in the census lists, planning to use the titles in a swindle.

The age of Realism

In the 1840’s, Realism began to emerge as an important literary trend in Russia. Its followers were influenced by the teachings of Vissarion Belinsky, a leading left-wing (liberal) literary critic. Belinsky believed that literature should give an honest picture of life and, at the same time, preach social reform. His view that literature should serve the needs of society became an established principle in Russian criticism during the later 1800’s. This view continued to influence the choice and treatment of themes in Russian prose well into the 1900’s.

Early Realism.

Russian literature of the 1840’s and the 1850’s had both Romantic and Realist traits. Early Realists combined Romantic sentiments with more realistic portrayals of social and political problems.

Ivan Turgenev, an outstanding novelist and playwright, displayed a deep understanding of Russian society and people. A Sportsman’s Sketches (1852) helped stir public sympathy for Russia’s serfs, depicting them as kind and dignified, and portrayed landowners as crude and insensitive. In Rudin (1856), Turgenev shows the traditional superfluous man as a frustrated liberal. The novel Fathers and Sons (1862) is superior to Turgenev’s other works in dramatic content and in character analysis. It shows the nihilists (radical Russian youths of the early 1860’s) as strong-willed and disrespectful of authority and tradition. They want to change Russian society, but the country is not yet ready for great change. The hero, Bazarov, dies inactive and frustrated. One of Turgenev’s favorite themes was young love, the subject of Asya (1858) and First Love (1860). In First Love, a boy experiences his first crush, only to learn that the girl has become his father’s mistress. Turgenev’s most successful play, A Month in the Country (completed in 1850), tells a similar story. A girl and her guardian compete for the love of a young tutor.

The novelist Ivan Goncharov tried to convince Russian liberals that only practical action, not lofty sentiment, could lead to social reform. In his novel Oblomov (1859), the superfluous man is Oblomov, a well-bred landowner and a charming and intelligent man whose almost total failure to act keeps him from achieving the dreams of his youth. After this novel, Russians began to refer to inactivity within the privileged class as “Oblomovism.”

Alexander N. Ostrovsky, one of the most popular and productive Russian dramatists, wrote plays that critically depicted the middle classes. His use of everyday Russian speech gives his work strong national appeal. Ostrovsky’s villains, products of the merchant world, are greedy, dishonest, and dominating. Ostrovsky’s greatest play, The Storm (1860), tells the tragic story of a merchant’s wife who is driven to suicide by her domineering mother-in-law.

Sergey Aksakov, another leading writer of the 1850’s, based his vivid descriptions of nature and people on childhood experiences. Unlike other Russian Realists, Aksakov neither attacked nor defended Russian society in his writings. His works include Family Chronicle (1856) and The Childhood of Grandson Bagrov (1858).

The 1860’s and 1870’s

brought an end to Romanticism in Russian literature. Russian Realists emphasized social conditions in their works. A simpler prose replaced the elegant style of Romanticism. The novel became the principal literary form. Many novels had vivid characters but little plot structure. As in the rest of Europe, many were first published serially in journals. Prose fiction and literary criticism served as means by which to discuss important issues in society, such as the position of the newly liberated serfs or the role of women.

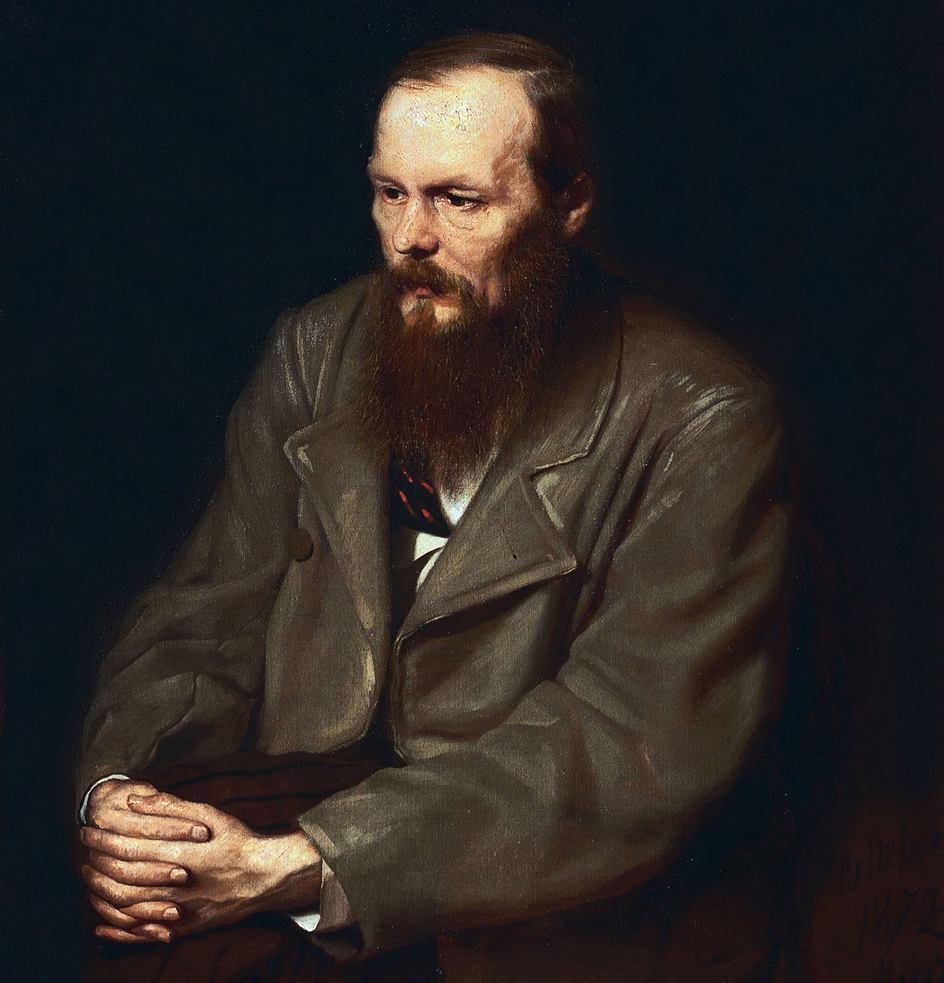

Fyodor Dostoevsky was another great Russian novelist. His works are famous for their dramatic portrayals of inner conflicts and their psychological depth. His characters experience violent spiritual struggles between their belief in God and their strong sense of pride and self-centeredness. Crime and Punishment (1866), Dostoevsky’s most exciting novel, describes the drama of a murderer who is tortured by his conscience. The hero, Raskolnikov, is spiritually redeemed when he finally confesses his crime and accepts punishment. The Brothers Karamazov (1879-1880), Dostoevsky’s last and greatest novel, tells about the murder of an evil man by one of his four sons. The symbolic redemption of the other sons represents the author’s faith in the saving power of God.

Russian Realism was a large and varied movement. Other important novelists include Nadezhda Khvoshchinskaya, Nikolai Leskov, and the satirist Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin. The foremost poet of the Realist era was Nikolai Nekrasov, whose verse often addressed the same social concerns as prose of the time.

Late Realism.

Alexander III, who became czar in 1881, opposed many of the reforms made by his father, Alexander II. Themes of despair and bitterness under the czar’s harsh rule appeared in Russian writings of the 1880’s and 1890’s. Stories and plays became the major literary forms of late Realism.

Anton Chekhov was a leading writer of short stories, short novels, and plays. Many of his works deal with the boredom and frustration of life. “Ionych” (1898) tells the story of a sensitive, idealistic doctor who becomes lazy and conceited as he grows older. The play The Three Sisters (1901) describes a family whose members are too weak-willed to change their dull lives. Sakhalin Island (1893-1894) describes the notorious prison colony in the Russian Far East, which Chekhov visited in 1890.

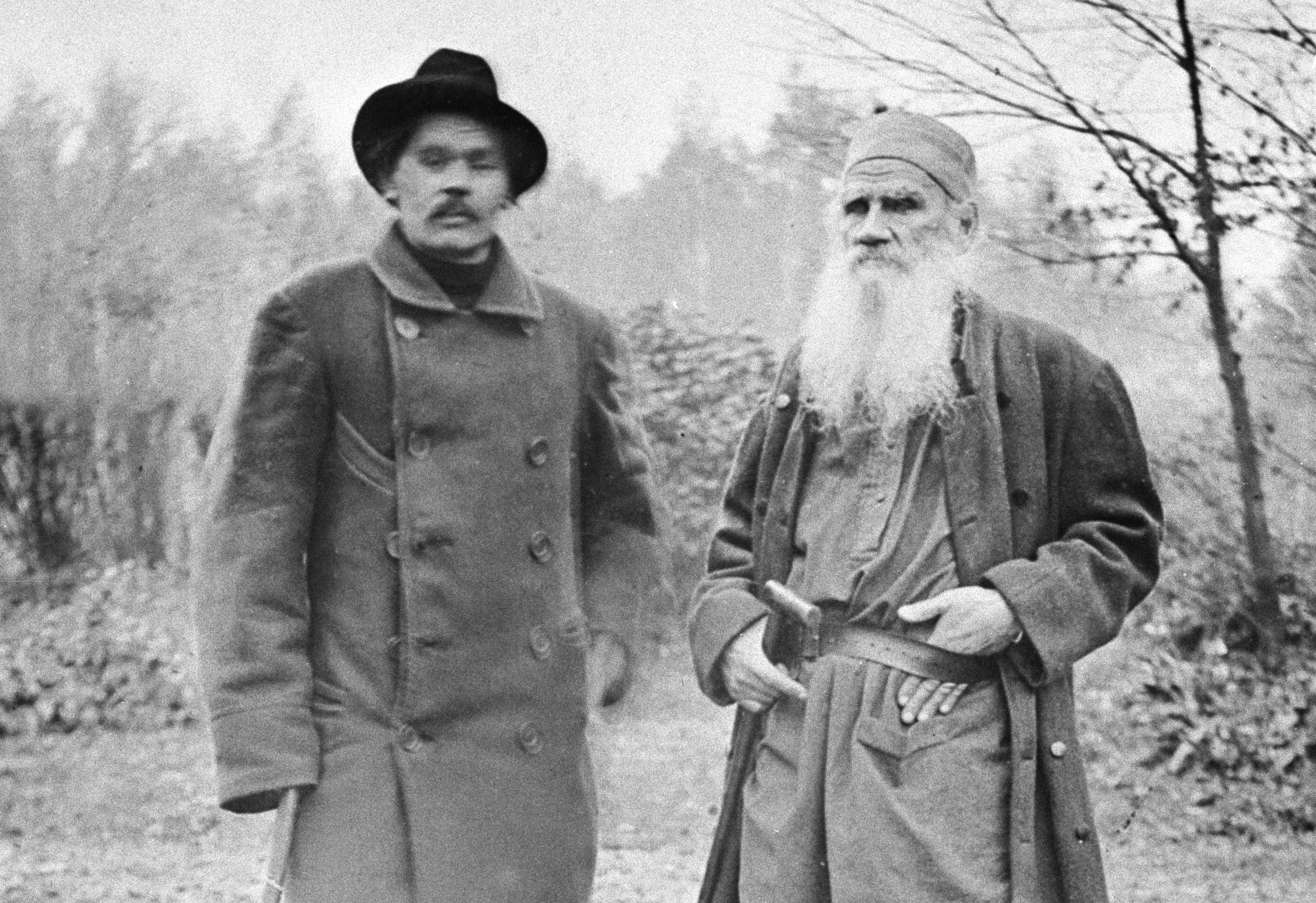

Maxim Gorki, the last of the great Russian Realists, wrote novels, plays, and stories. His early works de scribe the terrible poverty of the lower classes. Gorki’s most famous play, The Lower Depths (1902), dramatizes the miserable lives of the inhabitants of a cheap hotel. A frequent theme of Gorki’s later works was the decline of the upper middle class, shown in the novel The Artamanovs’ Business (1925). Gorki also wrote a multivolume autobiography and published reminiscences of his meetings and friendships with such leading Russian authors as Tolstoy.

Literary revival

A spirit of revolution spread throughout Russia from the 1890’s until the 1920’s. This period is now often described as the Silver Age. It was a time of social upheaval and transition in Russia and also of tremendous vitality and renewal in the arts, especially literature.

Symbolism

in Russian poetry and fiction began in the mid-1890’s. The Symbolists rejected the Realist portrayals of everyday life and its problems and disapproved of the artistic standards of many Realist writers. Symbolists drew inspiration from earlier Russian authors, particularly Tyutchev, Lermontov, and Dostoevsky, as well as from other European writers. Followers of the movement returned to the dreams and fantasies of the Romantics. Some concentrated on religious and philosophical theories, while others considered music the highest art form.

Leading Symbolists included Andrei Bely, Alexander Blok, and Zinaida Gippius. Bely was an outstanding novelist and also a poet. His novel Petersburg (1913-1914) depicts the Russian capital as a place where Eastern and Western philosophies meet and conflict with almost explosive violence.

Blok, a poet and playwright, expressed his religious ideals in his early works. His later poetry describes what he saw as the ugliness of the world. Blok’s famous long poem, The Twelve (1918), interprets the Russian Revolution of 1917 as a troubling but effective spiritual purification of Russia.

Gippius wrote poetry, plays, and stories, as well as literary criticism under the name Anton the Extreme. Her writing often expressed despair at the conditions of human life.

Leonid Andreyev combined elements of Realism and Symbolism in his works. He wrote sensational stories with themes of sex, madness, and terror. Examples of this style include the short story “The Red Laugh” (1904) and the play He Who Gets Slapped (1915).

Another leading writer of the early 1900’s was Ivan Bunin. Although he was not a Symbolist, his work, dominated by themes of love and death, resembles the works of the Symbolists. Bunin’s masterpiece, “The Gentleman from San Francisco” (1915), is a story about an American who works too hard and is unable to enjoy life later. In 1933, Bunin became the first Russian to receive the Nobel Prize in literature.

Post-Symbolism

grew out of Symbolism around 1910 and rejected the vague, philosophical works of the Symbolists. The Acmeists, one of the most important Post-Symbolist groups, wrote poetry that focused on the present world with clear-cut images and more concrete language. The word acme means highest point. A Symbolist who was critical of the group suggested the name Acmeists as a way of satirizing the poets. But the group itself adopted the name as a reminder of their goal to achieve a more perfect kind of poetry. Nikolai Gumilyov became known for his poetry about seafarers and safaris as well as his literary criticism. Osip Mandelshtam was absorbed with philosophy, religion, and aesthetics (a branch of philosophy that tries to establish basic rules for interpreting and judging the arts). Anna Akhmatova wrote lyric poems that suggested the psychological depths of Realist novels.

The Futurists formed several competing radical Post-Symbolist groups, all departing from traditional poetic themes and diction (word usage). Vladimir Mayakovsky, the most famous Futurist and an outspoken Communist, shocked readers with his strong language, innovative rhyming, and unusual imagery. Velimir Khlebnikov wrote poetry that drew from Slavic antiquity, folklore, and nature more than from the urban topics that fascinated most Futurists.

Boris Pasternak, one of the greatest poets of the 1900’s, created highly original poetry about nature and life. His early prose was strikingly experimental. Marina Tsvetaeva, another great poet, experimented with sounds and words. Her works include lyric poems, plays, and long poems, some based on classical Greek myths or the plots of Russian folktales. She strongly influenced later generations of Russian poets.

Silver Age poets experimented with verse forms and developed a new kind of long poem with varied meters and strong psychological interest. Meter is the pattern of rhythm in a poem. However, most Russian poetry in the early 1900’s still followed traditional patterns of rhyme and meter.

Soviet literature

The Russian Revolution of 1917 marked the beginning of a new era in Russian literature. For a few years, many writers engaged in creative experimentation. Then, the new Communist government tightened censorship, which had also existed under the czars. The Communist government came to power in 1922, after a civil war between Communists and anti-Communists. The government established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R., or Soviet Union). Many writers who opposed the Communist government left the country or were imprisoned or executed. Those who remained had to serve the interests of the state or stop writing. They were not allowed to criticize the government. Writers were told to describe Soviet life as happy and prosperous.

From 1917 to 1928.

Following the revolution, publishing houses closed and book production and sales dropped as a civil war devastated the economy. Newspapers and magazines became political tools of the Communist Party. Printing presses were taken over by the state. The government encouraged the development of a proletarian literature to express the interests of Russian workers and peasants. However, few works of value were written during this period.

Russian literature rebounded during the 1920’s. The government restored some literary freedom, reopened publishing houses, and permitted literary criticism to resume. Many new young poets and novelists in the Soviet Union at this time became known as fellow travelers (people willing to cooperate with the Soviet regime though they did not actively support it). Isaak Babel’s series of stories, Red Cavalry (1926), described the often horrifying events of the civil war that followed the Russian Revolution. Leonid Leonov, inspired by Dostoevsky, also explored the psychological effects of the revolution on the Russian people. His greatest novels are The Badgers (1924) and The Thief (1927). Yevgeni Zamyatin’s novel We (1921) described a dismal, distant future. It was not published in the Soviet Union until decades later. However, after it appeared in English translation in 1924, We influenced such works of Western science fiction as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949).

The period of industrial literature

began in 1928 with the Soviet Union’s first five-year plan. This program aimed, in part, to build up Soviet industry. Writers were expected to produce works dealing with economic problems. Factory and production novels began to appear in the Soviet Union, describing the building of a factory or the organization of collective farms. Most of this literature is considered inferior, but a few works, such as Cement (1925) by Fyodor Gladkov or Time, Forward! (1932) by Valentin Kataev, are interesting and skillfully written.

The period of Socialist Realism

started in the early 1930’s. The government, headed by Joseph Stalin, clearly believed that literature was extremely important. It banned private literary associations and established a Union of Soviet Writers. All professional writers were required to join the union, which endorsed the new doctrine of Socialist Realism. According to this doctrine, the main purpose of literature is to portray the building of a socialist society. A socialist society is one that emphasizes public or community ownership of all property that produces goods and services. The union ordered Soviet authors to produce optimistic works that were easy to understand and similar to the style of Tolstoy and Gorki. Censorship eliminated undesirable material from manuscripts, and writers soon learned to censor themselves. Writers who ignored the doctrine were expelled from the union. This meant the end of their careers, and some writers were imprisoned or even killed.

Historical literature became more common during the 1930’s and early 1940’s. The scholar Yuri Tynyanov wrote novels set in the 1800’s based on his research on literary history. One of the finest works about the revolution and the civil war was The Quiet Don (1928-1940) by Mikhail Sholokhov. This long epic novel tells the story of a young Cossack whose happiness is destroyed by the tragedy of war. Sholokhov received the Nobel Prize for literature in 1965.

World War II (1939-1945).

During the war against Germany from 1941 to 1945, the Soviet government gave writers greater freedom, hoping to build the nation’s morale. Themes of individual suffering and death dominated this period. Days and Nights (1943-1944) by Konstantin Simonov was one of many patriotic war novels. Not long after the war ended, the government reestablished strict controls over literature. It also forced several leading authors out of the Union of Soviet Writers. These writers included Akhmatova and Mikhail Zoshchenko, a noted humorist and satirist.

For most of the time from 1930 to 1953, writers did their best work “for the desk drawer” and only published it after Stalin’s death in 1953. Lidia Chukovskaya’s short novel Sofia Petrovna, written in 1939, tells how a good Soviet worker and mother watches as friends and co-workers are fired and arrested. She finally goes mad when her son, too, disappears into prison and then a labor camp. Playwright and prose writer Mikhail Bulgakov died in 1940, but his brilliant novel The Master and Margarita was not published until the 1960’s. In the early 1950’s, some of the most prominent Jewish writers in the Soviet Union were arrested and many of them were killed, especially those who wrote and published in Yiddish.

Post-Stalin Soviet literature.

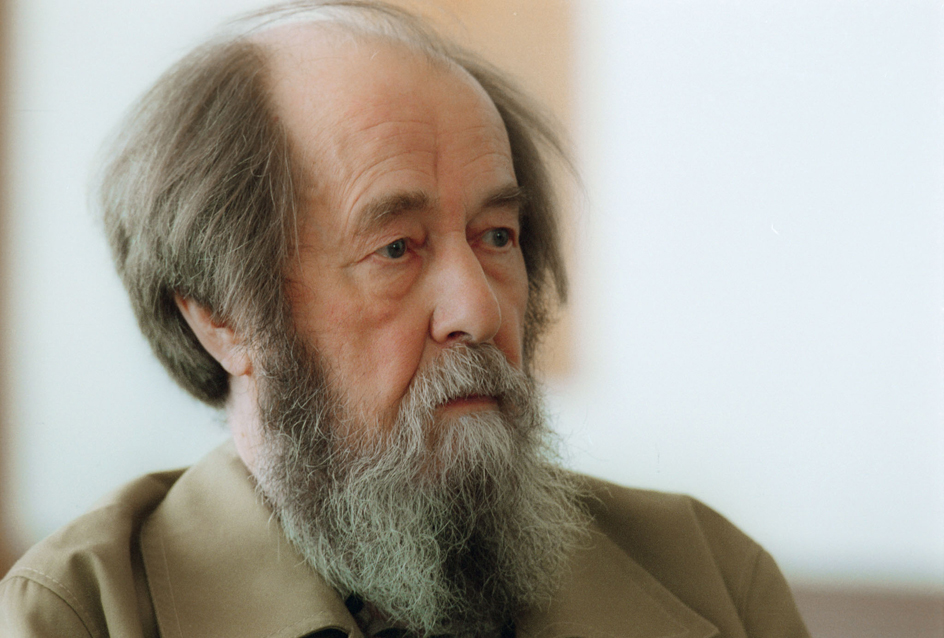

Stalin’s death was followed by a period of relaxed restrictions in Soviet life and literature. This change became known as The Thaw, from the title of a short novel written by Ilya Ehrenburg in 1954. In contrast to the policy of describing Soviet life as happy and optimistic, Ehrenburg wrote about frustrated, lonely people. The height of freedom during The Thaw was marked in literature by the publication in 1962 of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. This short novel describes Soviet labor camps in Stalin’s time. Solzhenitsyn himself had spent years in a labor camp, and one of his life’s goals was to record the history of people’s suffering under Stalin’s tyranny.

A number of young liberal writers appeared in the Soviet Union during the 1960’s. Three popular young poets were Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Andrey Voznesensky, and Bella Akhmadulina. They all spoke up for freedom and creativity in Soviet life. In “Babi Yar” (1961), Yevtushenko attacks the prejudice against Jews in the Soviet Union (see Babyn Yar). The main theme of Voznesensky’s work is self-analysis through personal experience. Akhmadulina wrote about the creative personality’s conflict with the expectations of polite society.

Several talented young prose writers, including Vasily Aksyonov, wrote about the shortcomings of Soviet life. Vasily Shukshin and other writers described the hardships suffered by farmers and other non-elite members of Soviet society. Science fiction became popular, reflecting excitement at new discoveries and the successes of the Soviet space program. The brothers Arkady and Boris Stru gatsky were the most prominent authors of Soviet science fiction, writing many stories and novels together.

Censorship in the Soviet Union prevented many works from being published, though typewritten or mimeographed copies of some of the manuscripts circulated secretly. Mimeograph machines made duplicate copies from a stencil. This type of self-publishing became known as samizdat. Some Soviet writers published works abroad that had not been officially published in their own country. In 1957, Boris Pasternak’s novel Doctor Zhivago appeared in Italy. Pasternak was awarded the 1958 Nobel Prize for his works, including this novel. He refused the prize under pressure from the Soviet government.

Andrey Sinyavsky, writing under the name of Abram Tertz, wrote several short stories that were published abroad beginning in 1959. Sinyavsky’s works, including The Trial Begins, describe the terrors of life in a police state. Sinyavsky was arrested in 1966 and imprisoned in a labor camp until 1971. In 1973, he was allowed to emigrate to France. The First Circle by Solzhenitsyn was published in the West in 1968. The novel tells about the life of political prisoners in a research institute during the Stalin era. Solzhenitsyn won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1970. He was exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974 but returned to live in Russia in 1994, after the Soviet Union had broken up.

Joseph Brodsky was forced to leave the Soviet Union in 1972, though his poetry and his translations from English and Polish had no clear connections with politics. Brodsky won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1987. He was named poet laureate of the United States for 1991 and 1992, the first foreign-born poet so honored.

Modern Russian literature

From 1970 to 1991,

political restrictions made publishing difficult in the Soviet Union. But many writers continued to resist or stretch the rules of Socialist Realism. Valentin Rasputin wrote about the decay of morals and standards and the loss of cultural traditions in rural areas due to neglect by the centralized Soviet government. Vladimir Voinovich wrote a humorous satire of Soviet life in The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of Private Ivan Chonkin (1975). Yuri Trifonov dealt with moral dilemmas faced by Soviet intellectuals in such works as Another Life (1975) and Old Man (1978).

Venedikt Erofeev’s short novel, translated as Moscow to the End of the Line (1970), was first published abroad in samizdat and became a cult favorite. The book conveys the reflections of a thoughtful alcoholic on a short train ride and suggests the voyage of Russia in search of herself. Chingiz Aitmatov and Fazil Iskander became important Soviet authors, writing in Russian about characters, events, and concerns in Abkhazia, Kazakhstan, or Kyrgyzstan. Such experimental underground poets as Gennadi Aigi, Dmitri Prigov, Lev Rubinshtein, and Vsevolod Nekrasov employed styles of writing very different from officially published poetry.

In the mid-1980’s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced a policy of glasnost (openness) that greatly relaxed censorship and led to freer public expression of information and opinion. The Soviet Union began publishing uncensored works of such important Soviet writers as Akhmatova, Bulgakov, and Pasternak. Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago and Zamyatin’s We were published in the Soviet Union for the first time in 1988.

The Gorbachev period and the following years of political transition in Russia saw the massive publication of translations from foreign languages and also of works by formerly suppressed writers. They included works by Tsvetaeva, Mandelshtam, and Solzhenitsyn and by such religious thinkers as Nicolas Berdyaev, Vasily Rozanov, and Lev Shestov. Several talented women writers gained popularity, including Liudmila Petrushevskaia and Tatiana Tolstaya, a distant cousin of Leo Tolstoy. Such prominent poets as Olga Sedakova, Boris Slutsky, and David Samoilov were read more widely than ever. The era of Soviet literature ended in 1991, when the Soviet Union broke up into many independent countries.

Russian literature today

is marked by dynamism and diversity, though no clear trends have emerged since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Many new writers have gained prominence. In general, poets and fiction writers no longer enjoy the high cultural status they had in the imperial and Soviet periods, and it is generally harder now for a professional writer to make a living.

Vladimir Makanin has written novels that treat the guilt of Russian intellectuals during the Soviet period. Viktor Erofeyev and Vladimir Sorokin write fiction dealing with sex, violence, horror, absurdity, and power used for evil, often using obscene language that was banned from print during the Soviet period.

Viktor Pelevin’s fictional topics range from the everyday deceptions of the Soviet era to the negative impact of economic changes in post-Soviet Russia. Pelevin’s works contain a strong element of mythology and great philosophical sophistication. Liudmila Ulitskaya is one of the most popular Russian prose authors of the early 2000’s. Her works often trace the history of fictional families whose fate seems to have been formed in the Stalin period. Olga Slavnikova’s novel 2017 (2006) combines near-future science fiction with the folk traditions of miners in the Ural Mountains.

Freed from the pressure of Socialist Realism, many different forms of fiction have flourished in Russia. Boris Akunin (the pen name of Grigory Chkhartishvili) and Alexandra Marinina write popular and successful series of detective novels. Russian fantasy, which was restricted to children’s literature in the Soviet period, emerged partly from reading J. R. R. Tolkien. However, it also takes inspiration from Russian folk mythology. Popular fantasy authors include Nik Perumov and Sergei Lukyanenko. Science fiction continues to be eagerly read, though many of the works are dark, in contrast with the optimism of most Soviet-era works.

Important Russian poets of the early 2000’s include Arkadi Dragomoshchenko, Elena Fanailova, and Viktor Krivulin. The censorship of the Soviet period kept the classical forms of Russian poetry largely intact, but now a reader is able to find all kinds of formal variations, from Classical verse by Vladimir Gandelsman to free verse by Polina Barskova. Maria Stepanova has produced new developments in traditional poetic forms. Marianna Geide uses serious traditional language to explore modern topics.