Sculpture is one of the most interesting and complex of the arts. It ranges from Michelangelo’s powerful carvings to African masks worn in religious ceremonies. It also includes stone statues that decorate cathedrals and metal mobiles that sway gracefully in the air.

A piece of sculpture can be small enough to stand on a table, or as large as the Statue of Liberty. But whether large or small, sculpture tends to have a monumental quality—the quality of grandeur and nobility in a work of art. Large-scale sculpture is often called monumental because of its size. However, even the smallest piece of sculpture has the power to express noble and grand ideas.

The art of sculpture probably developed in association with religious and magical practices. Sculpture emerged as an art form about 20,000 years ago, during the Paleolithic Period (Old Stone Age). Prehistoric people carved small statues from such materials as bone or ivory. They probably used these carvings in burial or fertility ceremonies. They modeled similar objects in clay. The word sculpture originally meant cut and implied the technique of carving. However, modeled objects are also called sculpture.

The importance of sculpture

As a record of history.

Sculpture is extremely valuable for the information it can supply about the development of human culture. Sculpture can tell us much about the way of life of a particular people or period by physically representing the ideas and ideals of a civilization.

In India, China, and other Asian civilizations, sculpture is used to aid contemplation. Such Asian religions as Buddhism and Hinduism stress the eternal, invisible powers of the universe rather than the temporary, observable realities of the everyday world. Through contemplation of sculptured images, Asian peoples seek to understand these divine powers and to become united with the eternal. Much Indian sculpture is devoted to images of Siddhartha Gautama, known as Buddha, the founder of the Buddhist religion. The Seated Sakyamuni shows the traditional image of Buddha on a throne meditating in the lotus position. Sakyamuni is another title given to Buddha.

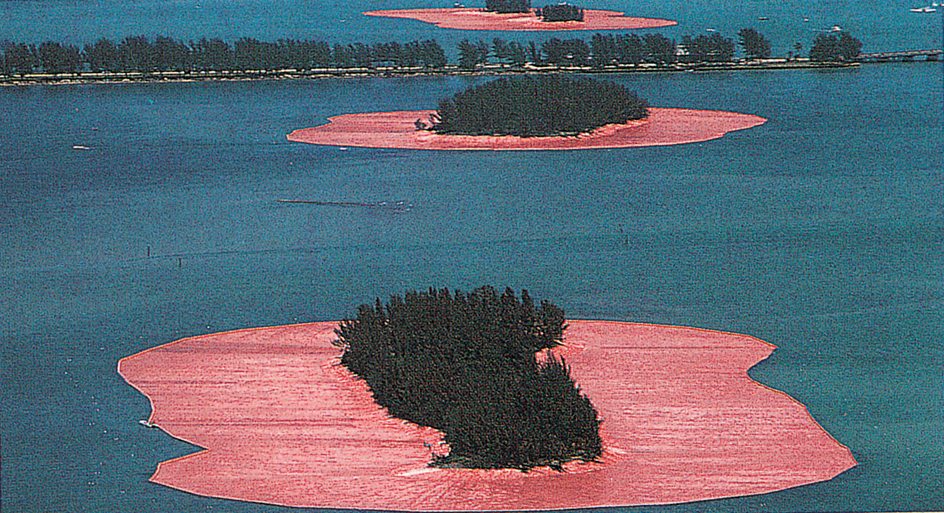

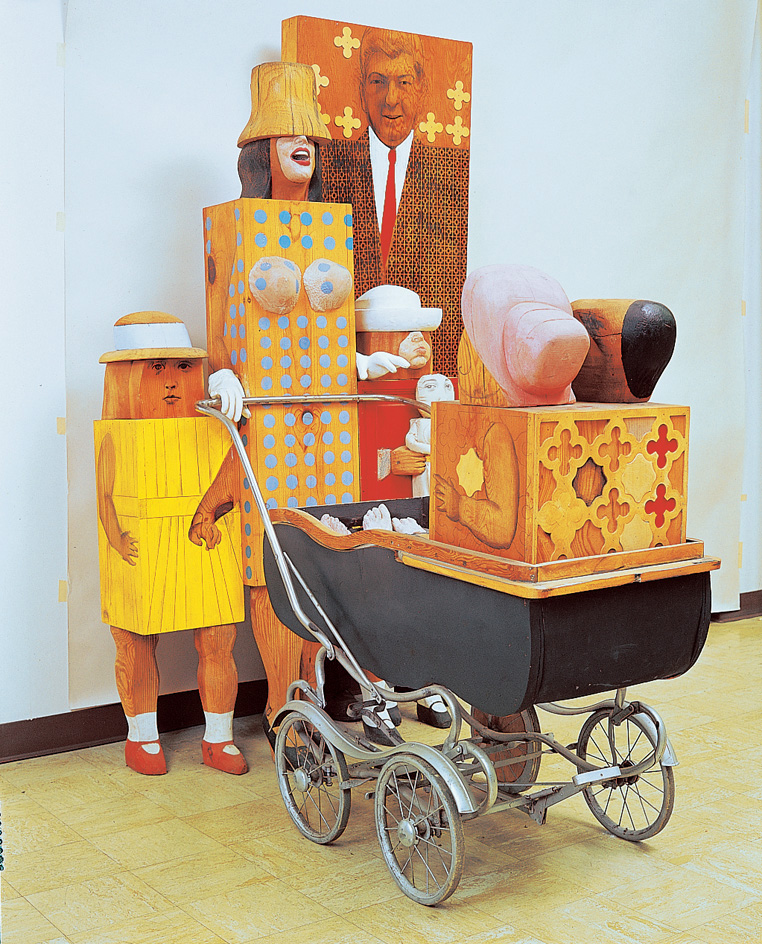

Some modern artists create sculptures that comment on the ideas, ideals, and social issues of their society. The American artist Judy Chicago dealt with feminist concerns in The Dinner Party. The work consists of a table with 39 individually designed place settings symbolizing 39 historically important women.

Sculpture also provides us with a record of the everyday life of a particular culture. Much sculpture is extremely durable. It has survived as a major source of our knowledge about such ancient cultures as Egypt, Babylonia, Mesopotamia, Assyria, and Persia. For example, the Votive figures from Mesopotamia illustrate the clothing styles of that society.

As monuments and memorials.

Sculpture can be created from such long-lasting materials as stone or metal. Thus, it is the art form most suitable for monuments and memorials. This type of sculpture is called commemorative sculpture. In some civilizations, most commemorative sculpture represents important persons or great events. Notable examples are stone pillars called stelae carved by the Maya of Mexico and Central America. A stele was erected in a city plaza. The Romans created Trajan’s Column as a sculptural record of the Emperor Trajan’s victory over Dacia in eastern Europe during the early A.D. 100’s.

As artistic expression.

Many artists create sculpture to satisfy their creative need to communicate. Sculpture also allows them to express their own ideas and feelings, or simply to create an object of beauty. When we look at a piece of sculpture, we can ask ourselves: “What is the sculptor saying in this work?” or “Why do I find this work beautiful, profound, or disturbing?”

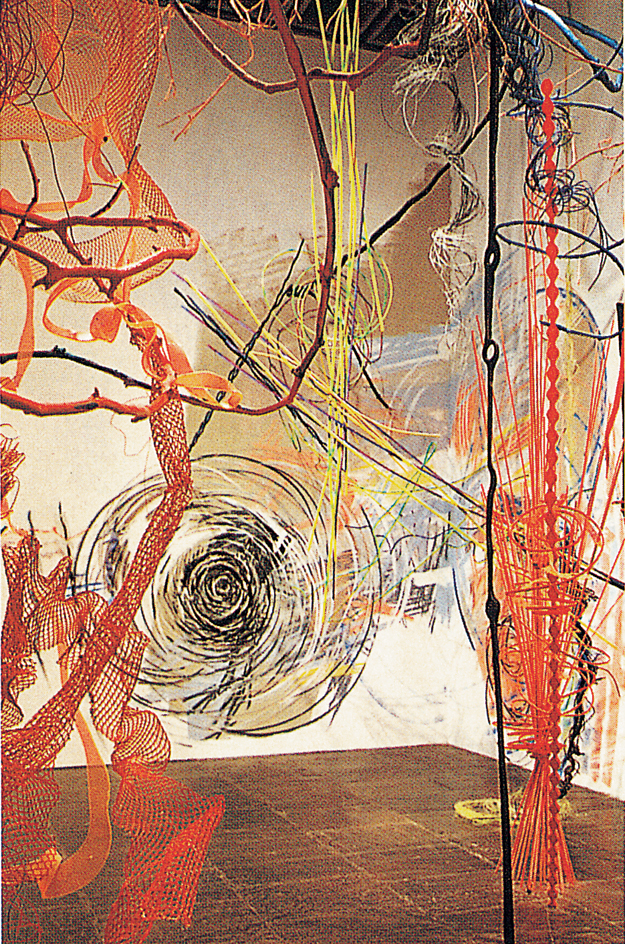

Much modern sculpture is created partly to satisfy the sculptor’s desire to experiment with new forms and materials. Many sculptors have been more interested in pure form—that is, the physical shapes of sculptured works—than they are in communicating some idea or theme. For this reason, many modern sculptures are abstract or nonrepresentational. That means they have no recognizable subject matter. The American sculptor Louise Nevelson constructed Mirror Shadow VIII of individual wooden components to create a feeling of power and mystery. Bird in Space shows the interest of the Romanian-born French sculptor Constantin Brancusi in such elements as balance and the treatment of surface.

As part of architecture.

Throughout history, sculpture has been closely associated with architecture, partly because similar materials and skills are used in both fields. In the temples of the Middle East, India, and ancient Greece and Rome, and in the cathedrals of Europe in the Middle Ages, the forms of the buildings blend completely into sculpture. This blending can be seen in the heads and bases of columns. It also appears in the moldings around doors and along the edges of roofs, and the abstract decorations. All these features show that the stonemason’s carving skill approached that of a sculptor.

Greek sculptors took particular care in applying sculpture to their temples. They made it blend so well with the architecture that the sculpture was not purely decorative. The Greek sculptors carved their works on panels and friezes (horizontal bands) on the sides of these buildings. They also carved on pediments (triangular segments below a sloping roof) and on metopes (square areas above columns).

Occasionally, sculpture that is part of the structure of a building also performs a function. For example, Greek sculptors made columns in the form of clothed female figures called caryatids, which actually hold up part of the building. Many medieval cathedrals have decorated waterspouts called gargoyles. The decorations consist of grotesque figures of animals or human beings (see Gargoyle).

Sculpture as an art form

Kinds of sculpture.

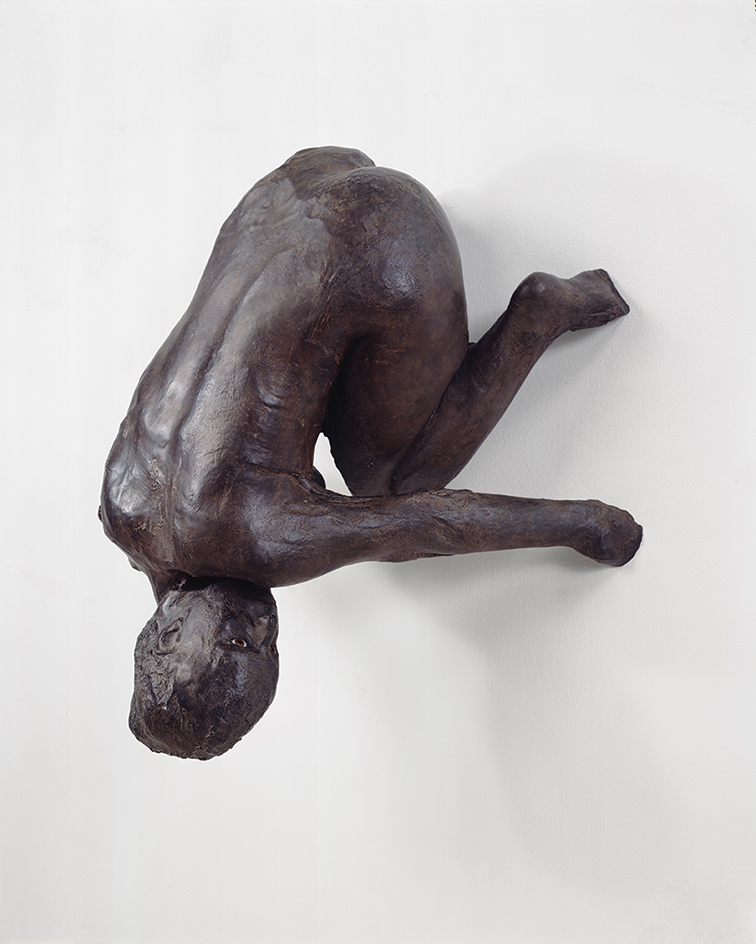

The most familiar kind of sculpture is called sculpture in the round or free-standing sculpture. It is modeled or carved on all sides. A sculpture in the round can have a main view, giving it a “back” and a “front,” as in certain sculptures of the human figure. Or it can be completely finished on all sides so that it can be viewed with pleasure from any angle, as can much abstract sculpture. In the past, some sculpture in the round was meant to be seen only from the front. The artist left the back of the figure rough and unpolished, with tool marks showing. This practice has provided much information about the methods of sculptors of the past.

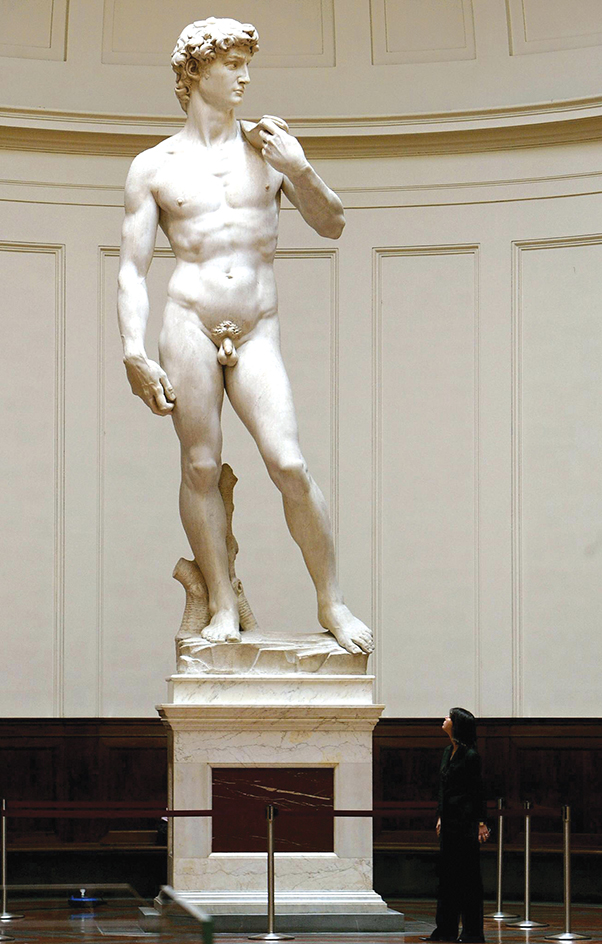

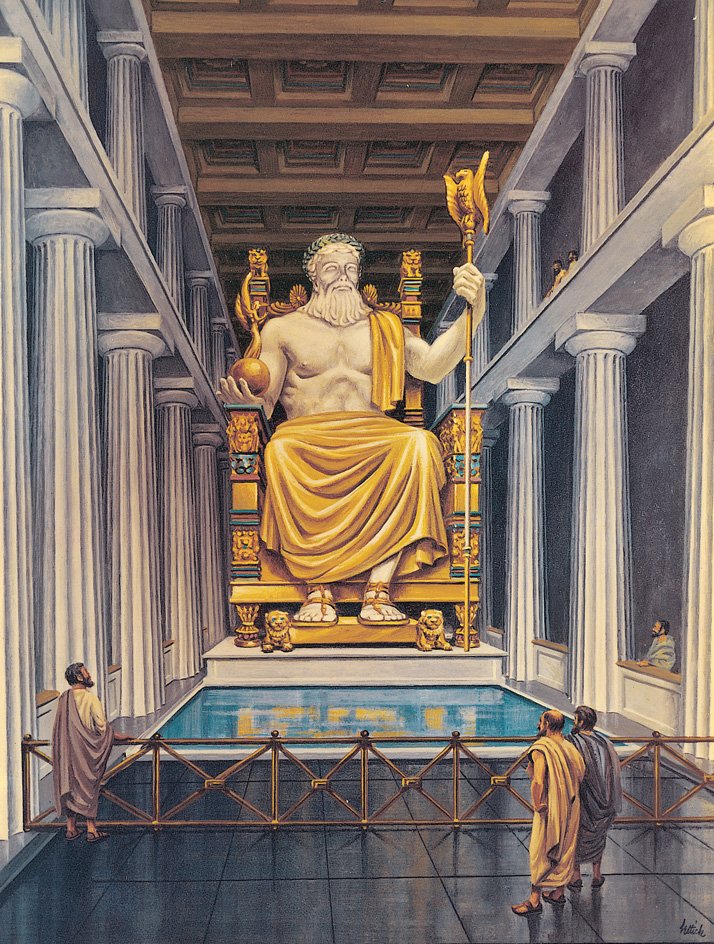

Sculpture in the round varies greatly in size and scale. Some statues are life-sized or larger. Statues that are somewhat larger than life-sized are said to be in heroic scale. If they are from several to many times larger than life-sized, they are in colossal scale. Two ancient examples of colossal sculptures were the statue of Zeus in Olympia, Greece, and the Colossus of Rhodes near the harbor of the island of Rhodes.

Sculpture that is completely attached to, or absolutely part of, a flat surface is called sculpture in relief. There are two kinds of relief work—true relief and intaglio. In true relief, the figure stands out from the surface, as in Lion fighting a bull. In intaglio, the figure is carved into the background. The intaglio technique was highly developed by the ancient Egyptians for decorating the massive outside walls of their temples. As used by the Egyptians, it is usually called low relief. This kind of relief is best seen in strong light, which makes the outlines of the figures stand out as sharp shadows.

Relief sculpture can be carved or modeled. Some of the early carved reliefs of the Egyptians are little more than engraved lines on stone. Many Greek reliefs are shallow. But they stand up from a flat surface in true relief. In some reliefs, the Greeks flattened off the forms nearest the viewer. They deeply undercut and rounded the forms at the back. Later Greek and Roman reliefs tend to have the nearer forms rounded, as in painting. The figures seem almost detached from the background, as in the Alexander Sarcophagus.

Reliefs can also be modeled in clay or wax and cast in bronze. Two famous examples of cast reliefs are the doors for the Florentine Baptistery by the Italian Renaissance sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti, and the new doors for St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome by the modern Italian sculptor Giacomo Manzu.

Form and treatment.

Sculptors use many elements found in painting. These elements include space, mass, volume, line, movement, light and shadow, texture, and color. But a painting has only two dimensions—height and width—because it is created on a flat surface. The painter can give only an illusion of depth. By contrast, sculptured forms have three dimensions. They have depth, or solidity, as well as height and width because the sculptor creates the forms in space. The terms mass and volume are used to describe the way sculptured forms occupy space. Mass describes the amount of bulk, solidity, or weight of a form in space. Volume refers to the amount of space occupied by a sculpture. Line, or the edges of a sculpture, encloses or defines the shape of the sculptured form.

Movement

is an important element of sculpture. Some sculptures seem to be completely at rest and suggest little or no movement. For example, the bronze statue of the Charioteer of Delphi has a simple outline and little detail. It appears powerful, solid, and calm. It stands firmly on its base, in complete balance. This kind of sculpture is called static (unmoving).

Sculpture that gives an impression of change, movement, and energy is called dynamic. Sculptors can create the illusion of movement in several ways. In Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, the Italian sculptor Umberto Boccioni created rhythms within the statue itself through the repetition of curved shapes. The figure seems to hurl itself through space in successive stages of continuing movement. Antoine Coysevox, a French sculptor, showed a figure in vigorous action in his statue of Mercury. When we look at such a figure, our eyes follow the lines of the body and the limbs. These lines lead in many directions, creating a feeling of movement.

Some sculptures actually do move. These works are called kinetic sculpture. The first and most original kinetic sculptures were the mobiles invented by the modern American sculptor Alexander Calder. As in Red Petals, the various elements of most of Calder’s mobiles are made of thin sheet metal. Some of them suggest swimming fish or leaves blowing on a tree. The metal shapes are linked by rods and wires to form a series of balanced pairs that are suspended from a single point. They rotate about each other in the lightest breeze.

Some artists build kinetic sculptures in which the various parts move mechanically. The modern French sculptor Jean Tinguely became famous for his complicated structures created out of scrap metal. They have mechanically moving parts that actually break apart, turning the sculpture into scrap once more. The sculpture’s “self-destruction” is part of the artist’s purpose.

Light and shadow.

A painter indicates form by creating light and dark shades. After this shading is completed, it cannot be changed. A sculptor creates an actual three-dimensional object that must depend on changeable natural or artificial lighting. Thus, the sculptor may have a conception of ideal lighting conditions for a particular work. In the case of a commissioned sculpture, the artist may want to study the site where the work will eventually be placed.

Texture.

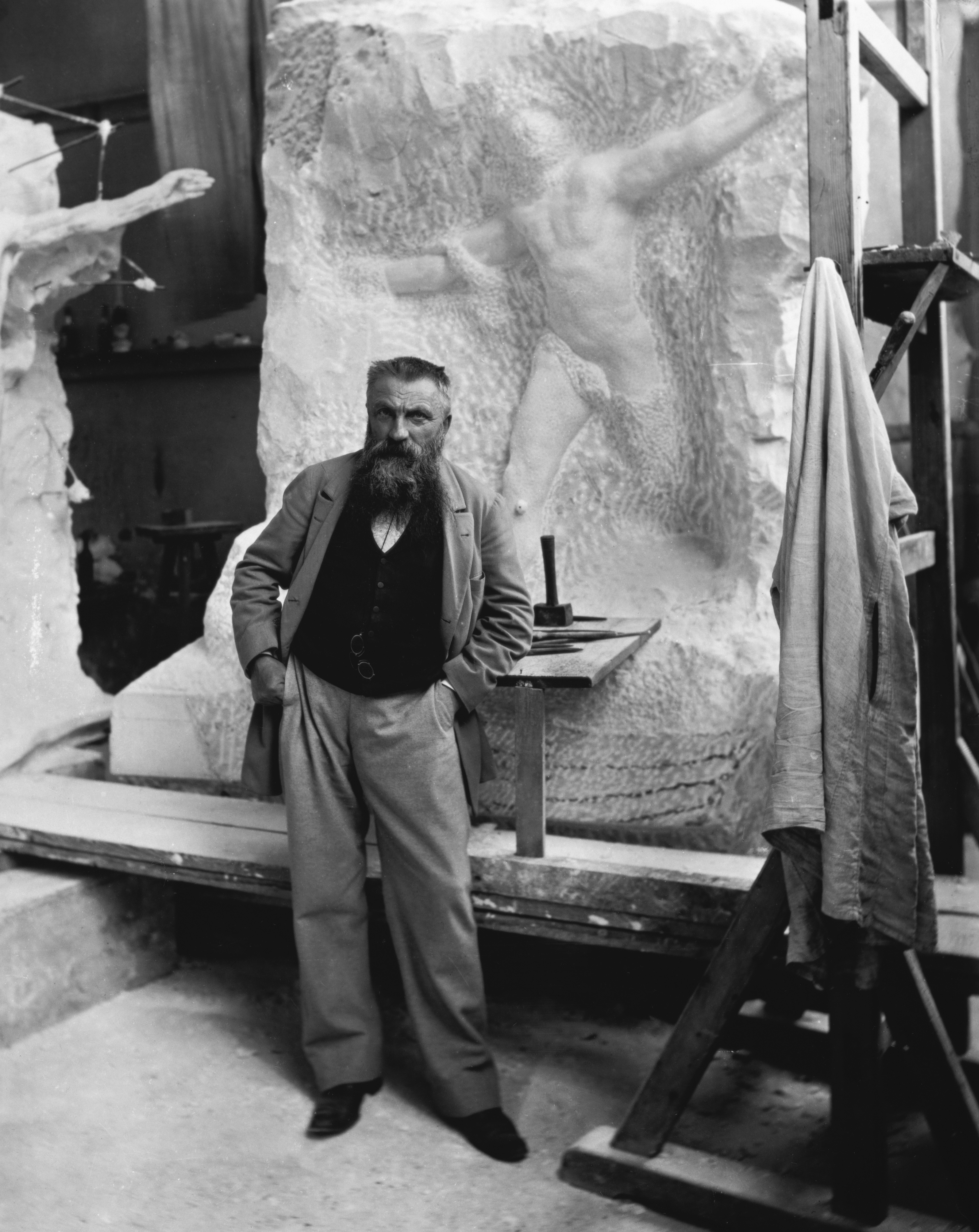

Because of the natural play of light and shadow, the sculptor also must consider the texture of the forms. The sculptor must decide whether to leave the surface of the work rough, or how far to go in giving it a smooth, highly polished surface. A rough surface, such as one showing the sculptor’s hand marks or tool marks, catches light and can give the sculpture a feeling of strength and power. A smooth, highly polished surface can make the work seem impersonal. Compare the French sculptor Auguste Rodin’s bronze Orpheus with the American sculptor David Smith’s stainless steel Cubi XIX.

Color.

Much sculpture is left the color of its material, whether it is bronze, marble, or wood. Many sculptors and patrons prefer the natural beauty of such materials. However, there is a long tradition of coloring sculpture. To make their works more lifelike, sculptors in ancient Egypt, ancient Greece, and other early cultures naturalistically painted the lips, skin, eyes, and hair of their subjects. Unfortunately, the colors have faded from most surviving sculptures of ancient Egypt and Greece. Many African and American Indian sculptures gain emotional intensity from their coloring. Examples include the Royal throne from Cameroon and the Transformation mask from the northwest coast of North America.

Today, many artists use colorful synthetic materials or complete their works with color. An example is Woman with Suitcases by the American artist Duane Hanson. The work is made of fiberglass and polyester combined with real-life accessories such as luggage and clothing.

Color produces many vivid effects. It can make heavy materials seem lighter and create a happy or gloomy mood. It can also make a sculpture resemble a painting created in three dimensions. Complicated forms become easier to understand. The sculptor may also be able to overcome certain difficult lighting conditions.

The sculptor at work

Carving and modeling have been the basic techniques throughout most of the long history of sculpture. In carving, a sculptor works with a solid block of wood, stone, or some other material. The sculptor visualizes the finished figure and then cuts and chips away the material until only the imagined figure remains. In modeling, the artist builds up the sculpture by adding layers of clay, wax, or some other soft, pliable material that will stick to, and blend with, itself.

The materials used in modeling are soft, brittle, or otherwise impermanent. Therefore, most modeled sculpture is turned into a more lasting form. From the earliest times, sculptors have preserved clay figures by baking them until they are hard. Figures made in this way are called terra cotta. This Italian term means cooked earth. Usually, only small figures can be made by this process, and they break easily.

A common way to make a modeled sculpture permanent is to cast it in metal or another hard material. First, the artist makes a mold of the modeled work. Into the mold, the artist pours a more permanent material–cement bronze, or aluminum, for example—and lets it harden. As long as the mold lasts, any number of replicas of the original sculpture can be cast. See Cast and casting.

The work of the sculptor today has changed in many ways from previous times. For centuries, sculptors trained as apprentices in workshops. Today, they train in art schools or universities. Most modern sculptors prefer to work alone or with one assistant rather than in a workshop. The work of many sculptors is known primarily through exhibitions at museums and by private dealers. Depending on the materials and the size, creating sculpture in advance can be expensive and risky, because few patrons request specific works. Sculptors often make a maquette (small-scale model) to show to buyers. After the artist finds a client, he or she then executes the full-size piece.

Through modern technology, the sculptor has the freedom to choose from a vast number of new materials. Artists commonly use such industrial materials as stainless steel, aluminum, plastics, and neon lights. They also use junk and discarded materials such as old wood or machine parts. The sculptor assembles these materials with glues, power saws, drills, and hammers. Such works are called assemblages.

Today, few sculptors carve in wood or stone. Carving is strenuous and time-consuming. It ties up the sculptor’s money in expensive materials. Modeling is much faster, cheaper, and more flexible. Modelers use soft materials such as wax, wet plaster, or clay. Their main tools are their hands But they also use trimming and shaping devices. Most sculptors make a maquette. They take it to a foundry where an enlarged copy is cast in metal under the artist’s supervision.

Because of the difficulties of casting, many sculptors work metal by hand. With such modern industrial equipment as electric arc and gas welding tools, an artist can cut and shape metal and join the pieces together. To finish their sculptures, modern artists use such industrial equipment as sandblasting machines or grinding tools. They can produce a patina (surface film) on bronze by applying heat and various chemicals to the finished work.

Beginnings

Prehistoric sculpture.

People of the Stone Age thought they recognized the forms of living things in such objects as bones, animal horns, and rocks. Prehistoric sculptors carved eyes or arms and legs in these objects to make them look like people or animals.

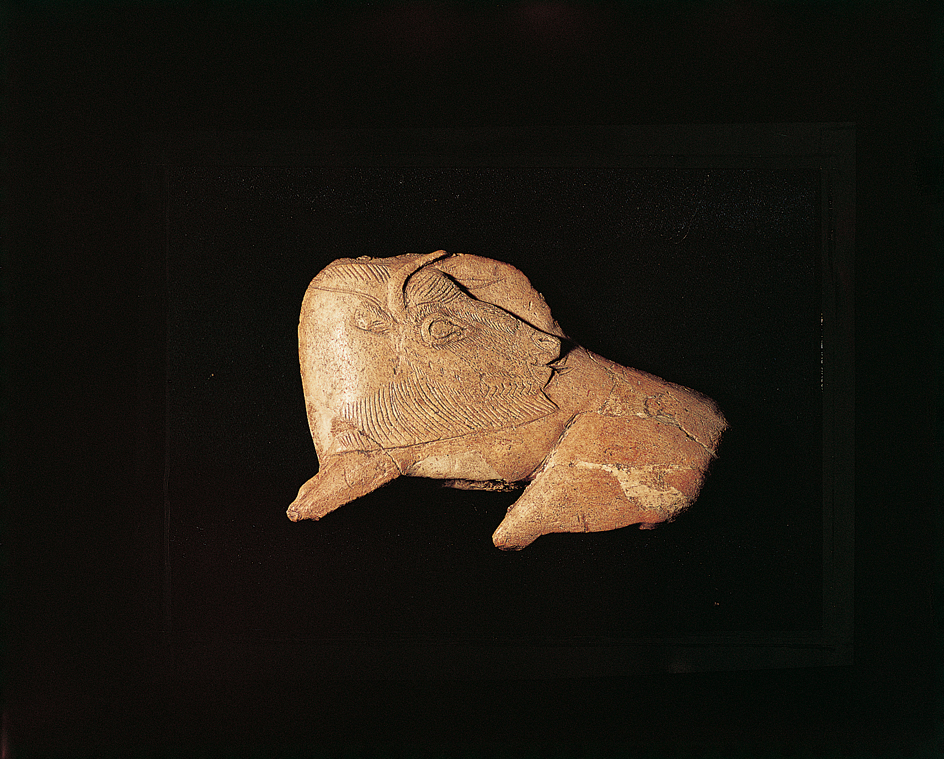

There were only a few subjects of prehistoric sculpture. All of them apparently had some magic significance. The figure of A bison with turned head and other animal sculptures probably represented animals killed by hunters. Figures of a plump woman, such as the Venus of Willendorf, may have represented the Mother Goddess, who gave life and food to people.

After prehistoric peoples learned to make pottery vessels by firing clay, they used this technique to make figurines. Terra-cotta figurines have been found in many parts of Egypt, Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), Mesopotamia (parts of modern Syria, Turkey, and Iraq). They have also been found in the Indus Valley (now Pakistan and western India). Although few details appear on these figurines, prehistoric sculptors obviously did try to emphasize such important physical features as an animal’s strong horns or neck, or a goddess’s breasts and buttocks.

Beginning about 3000 B.C., ancient civilizations produced many fine sculptures. By this time, artists had gained skill at working with such harder materials as stone and metals.

Middle Eastern.

Most early Mesopotamian sculpture consists of small-scale male and female figures, such as kings, priests, or deities. Sculptors showed their subjects in stiff poses and did not attempt to suggest movement or to portray actual persons. An example is the group of Votive figures created by Sumerian sculptors of southern Mesopotamia. Livelier scenes of everyday life appear mainly on stone reliefs decorating containers, furniture, and other objects.

During the era of the Assyrian Empire (900’s B.C. to 600’s B.C.), sculpture was used mainly as architectural decoration. The Assyrians carved colossal stone figures of bulls with human heads to stand beside palace gateways. Palace walls were decorated with reliefs made up of many scenes. These scenes told the story of complete military campaigns and other important events. Some of the finest relief carvings are those from Nineveh (an Assyrian city in what is now northern Iraq). They showed a royal lion hunt. Assyrian sculptors carved the movements and forms of animals more accurately and realistically than earlier sculptors did. But their human figures were stiff and unemotional. This is true both in relief carvings and in the few large figures that they carved in the round. See Assyria.

The Achaemenid Empire covered much of the Middle East and southwestern Asia from the 500’s B.C. to the 300’s B.C. Persian sculptors of the empire were interested in the patterns of animal limbs and muscles. An example of their work is the relief Lion fighting a bull. The Persians decorated buildings with large relief sculpture. But their finest work was on a small scale. Some of it shows clear signs of influence from classical Greece. Greek sculptors probably worked for the Persian kings. See Persia, Ancient.

The Hittites, who founded a great kingdom in Asia Minor after 2000 B.C., used architectural relief sculpture in a manner similar to the Assyrians. They also carved a number of large monuments from solid rock, showing kings, gods, or religious ceremonies.

Aegean.

The islanders who inhabited the Cyclades in the Aegean Sea about 3000 B.C. carved figures in white marble. Like the Cycladic marble figure, most of these figures were of women. The sculptors had no metal tools. But they rubbed the figures smooth with pebbles of emery. Archaeologists have discovered most of the figurines in graves.

During the 1500’s and 1400’s B.C., the Minoans of Crete made superb small figures of worshipers. Some of these figures were made of gold and ivory, and others of terra cotta. Still others were cast in solid bronze. The Minoans did not smooth or polish the bronze, so these figures have a rough finish. The figures show a vigor not developed elsewhere at this early date in history, as can be seen in the bronze figure of a Woman praying.

Egyptian.

A distinctive style of sculpture developed in Egypt about 3000 B.C. It continued with little major change for more than 3,000 years. Egyptian sculpture was made for limited purposes. It commemorated a person or event or served as a substitute for the activities of real persons.

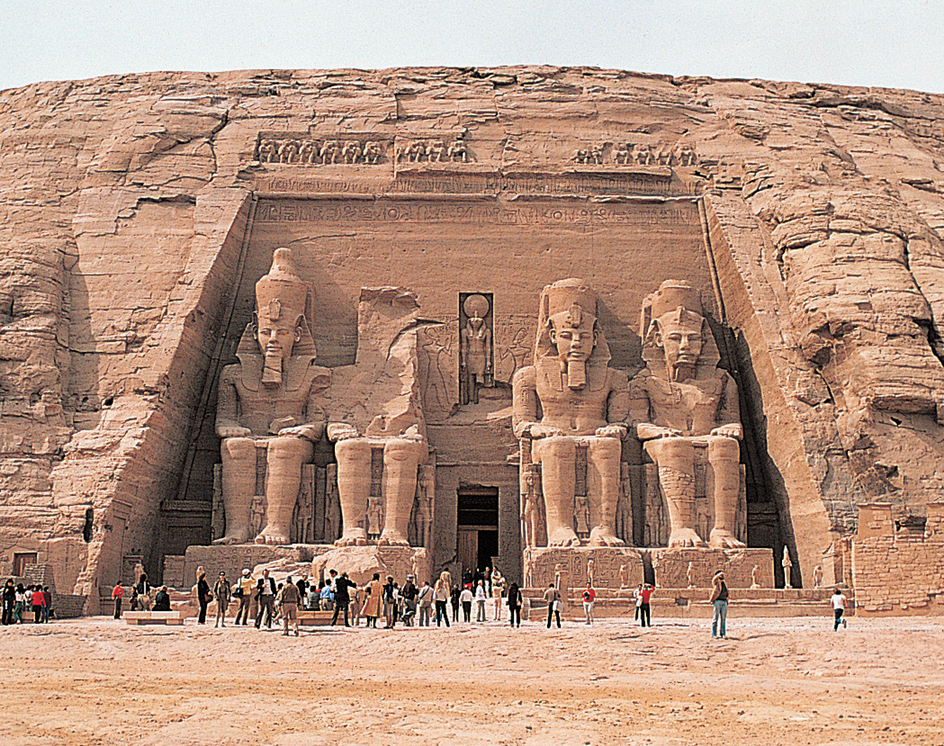

Commemorative sculpture includes King Mycerinus of Egypt and his queen and other great statues of kings and queens, whom the Egyptians regarded as gods. Some of these statues are colossal in scale. The seated statues of Ramses II, cut in rock at Abu Simbel, are more than 65 feet (20 meters) high. Reliefs covering the walls of temples commemorated religious ceremonies or such events as coronations and important military victories.

Egyptian sculptors also carved stone or wooden statues that were placed in tombs to represent the dead. These reliefs and modeled figures showed scenes of daily life similar to the activities the dead were expected to perform in the next world.

In carving the human figure, the Egyptians considered realistic scale unimportant. They showed a king much taller than his subjects or his enemies. Egyptian sculptors followed fixed rules that controlled the proportions of the parts of the body. These rules applied to sculptures ranging from tiny figures to colossal statues carved out of cliffs.

Tradition also required figures to have quiet, restful poses and expressionless faces. The Egyptians considered any vigorous action or realism unnecessary. Only for a short time during the 1300’s B.C. did some realism appear in figures and portraits.

Indus Valley.

The Indus Valley civilization flourished in what is now Pakistan and western India from about 2600 to about 1900 B.C. The two main sites of the Indus Valley civilization were along the Indus River. They were the cities of Harappa in the north and Mohenjo-Daro (also spelled Moenjodaro) in the south. Sculptures from these cities include small stone tablets that were used as seals, and figures of animals and human beings.

The seals show the rounded forms of bulls, elephants, and rhinoceroses, along with triangular, curved, and vertical signs. Such seals show the ability of the Indus people to create intaglio—sculpture in which figures are carved into the background—with delicate, curved lines.

The human and animal images were cast in metal, carved from stone, or modeled in clay. Indus Valley sculptors demonstrated a high level of technical skill in all these mediums.

Indus Valley sculptures have a repetition of curving lines that reflects the sculptors’ love of linear rhythm. Indus Valley sculpture also stressed harmonized form. This became a dominant characteristic of later sculpture in India.

Linear rhythm is apparent in the bronze Statuette of a dancer. The sculptor has captured the dancer when she is either pausing after a movement or is just about to move. The dynamic quality of this sleek figure is partly due to the rhythmic, angular thrusts of her arms, legs, and torso. The sculptor has also indicated movement by contrasting the linear rhythms of the torso and legs against the triangular right arm and the forward left leg. This contrast of linear rhythm with square and triangular shapes to produce movement is a characteristic of later Indian sculpture, both Buddhist and Hindu.

Indus Valley sculptors cast objects of copper, silver, and gold. Stone seals and the few surviving three-dimensional stone sculptures represent their subjects realistically and apparently had religious meaning. See Indus Valley civilization.

Asian sculpture

Asian sculpture is made up of diverse artistic traditions separated by time and geography. When connections exist in style or subject matter, those connections are usually due to the influence of religion, conquest, or trade. For example, Assyria, Mesopotamia, and Persia—the ancient civilizations of west and central Asia—produced monumental figurative sculpture. After the Muslim conquests of the A.D. 600’s, figurative sculpture ceased in these areas because Islam prohibited making images of living things. However, Islamic artists carved reliefs of motifs (repeated designs) and calligraphy (beautiful handwriting) as architectural decoration. Islamic decorative objects in ivory, metal, and wood have sculptural form.

Until the development of the International Style of modern art in the 1900’s, the notion of self-expression in sculpture did not exist in Asia. Traditional Asian sculpture was created primarily to communicate religious and political ideas, for ritual purposes, or to glorify a ruler. Few Asian sculptors are known by name. Sculptors rarely worked alone until the late 1800’s. These anonymous artists trained in workshops supported by religious institutions and the ruling classes.

India.

Some scholars believe that sculpture is India’s greatest artistic achievement. Over a period of 4,000 years, Indian sculptors created powerful works. The works are characterized by spiritual content and technical brilliance. India’s sculptural tradition is primarily based on two religions, Buddhism and Hinduism. However, monumental nonreligious sculpture was sometimes made to glorify a ruling dynasty.

Sculpture first flourished in India in the 2000’s B.C. That period is discussed in this article in the section Indus Valley. The beginning of traditional Indian sculpture can be dated to the 300’s B.C. and the establishment of empires that ruled most of south Asia. The influence of the sculptural style of Persepolis, the Persian capital in what is now Iran, may have played a role in developing the high artistic level of Indian sculpture as early as the 100’s B.C.

A sculptural style emerged in India that spread across Asia with Buddhism and through Hindu traders and merchants. This style was stimulated by religious doctrine, particularly the bhakti, or worship, cults. These cults required narrative reliefs of Buddhist legends as well as ornamental imagery to decorate both nonreligious and monastic religious sites.

From about the 100’s B.C. to the A.D. 500’s, sculptural activity flourished. This was due to the construction of many temples and other religious structures and the support of royal patrons. This sculpture represented spirituality through the appeal of the human body. Buddhist art dominated this period. Folk gods and goddesses incorporated into Buddhism were represented on the gates and stone railings of stupas (funeral mounds). Stupas contained relics of Buddha and were also symbols of the universe.

Buddha was not represented in human form until the period from A.D. 1 to 99. Images such as the Seated Sakyamuni express Buddhist teaching in a visual form. The sculptor communicates ideas through the image’s physical characteristics, gestures, dress, and surrounding figures. A workshop in the city of Mathura, India, carved this work. The same workshop probably also made images for Hinduism and the Jain religion. Some Mathuran Hindu deities produced about the A.D. 100’s already have multiple arms. This was a common feature of the art of later periods.

The Buddha image also appeared before A.D. 100 in Gandhara in present-day Pakistan. Gandharan Buddhist images are based on models from Greece and Rome. They are more realistic than those produced in central India.

The 400’s and 500’s marked a classical phase in Indian sculpture followed by a long period in which styles changed at a slow pace. Sculpture of this later period, sometimes called medieval, is dominated by Hindu images. Stone and bronze images reveal the increasing importance of rules and rituals in making sculpture. Bronze works express, through their smooth surfaces and rhythmic lines, philosophical ideas about existence. Sculptors borrowed from the language of Indian dance. They created works that rise above ordinary human activity and express profound religious truths. A common theme shows the Hindu god Shiva as Nataraja, Lord of the Dance. Many other works show the god Vishnu in various forms.

The Indian influence.

Traders and missionaries carried Indian culture throughout Southeast Asia. They also carried it to such Himalayan kingdoms as Nepal and Tibet. The great temple complexes of Borobudur in Indonesia and Angkor in Cambodia were heavily decorated with reliefs and with images in the round. These sculptures developed in response to the fervent worship of Buddhist and Hindu deities imported from India.

Borobudur was a great monastic and pilgrimage site. Its temple complex resembles an architectural mountain. It was created to symbolize the Buddhist universe. Its sculptures, are carved in dark-colored volcanic stone. They express serenity and harmony in their treatment of the human body. See Angkor.

China.

The Neolithic Period lasted from about 8000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. Sophisticated ceramic vessels with painted, inscribed, or applied decoration appeared throughout what is now China during that period. These containers apparently were ritual vessels.

During the Shang dynasty (about 1766 B.C. to about 1045 B.C.), skilled craftworkers used a new medium—bronze. But Shang bronzes retained the forms and functions traditionally associated with pottery. The vessels were produced by a unique process called the piece-mold method. Artists made models of clay and then a clay mold of the modeled work, into which bronze was poured. The outer mold was made of separate pieces rather than a single unit. Because the mold had to be destroyed to free the vessel, the object could not be duplicated.

Shang dynasty sculptors made elaborate bronze vessels for rituals of ancestor worship. Realistic and stylized motifs of human images and animals decorate these ritual containers. The animal motifs include buffaloes, serpents, dragons, and tigers. Bronze vessels for wine and grain were made in fantastic shapes with beautiful surface patterns. These vessels dominated Chinese sculpture from the Shang dynasty to about 200 B.C. Sculptors also worked in stone, bone, jade, ivory, clay, and wood during this period.

The life-sized figures in the tomb of the emperor Shi Huangdi near Xi’an, China, reveal monumental figure sculpture in China at least as early as the 200’s B.C. An example is the Kneeling archer.

Interaction with other cultures, including Buddhism, during the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) influenced the art of China. Buddhism spread throughout China from the A.D. 200’s to the 500’s. During this time, Chinese sculptors transformed the swelling, round forms of Indian rhythmic carvings into two-dimensional linear carvings in stone and bronze. Deities once portrayed as nude were clothed and their facial features simplified. In east Asian Buddhism, spiritual leaders called bodhisattvas became the focus of popular devotion. A bodhisattva is an individual who puts off personal salvation to help humanity. The Seated bodhisattva is dressed in the fine clothes of a prince. His body has disappeared beneath ribbonlike scarves and cascading drapery. The statue follows the conventions of Indian Buddhist sculpture, but the Chinese artist changed the way the figure is portrayed.

The Tang dynasty (618-907) carried the International Style of Buddhist art to central Asia and Japan. Tang sculpture became renowned for its realism. Buddhism ceased to be a major artistic force in China by the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368), and sculptural styles became static. Sculptors created small decorative works in ceramics, wood, and jade and other semiprecious stones in a style that continued with little variation to the 1900’s.

Korea.

Metalworking and advanced ceramic artistry in Korea were heavily influenced by China. Early Korean sculpturelike objects include golden crowns and stoneware vessels from the A.D. 400’s and 500’s, and porcelains from the 1000’s and 1100’s. The image-making tradition of Buddhist art inspired monumental figure sculpture in Korea.

The first Buddhist sculptures came to Korea from China. But by the 500’s, local sculptors were producing works based on Chinese models. By the 600’s, a distinctive Korean sculpture style had emerged in which delicacy and elegant curved rhythms indicate tranquillity and repose. Examples include sculptures found in the Sokkulam cave temple near Kyongju and the gilt bronze Buddhist triad excavated from Anap-chi Kyongju. Both are monuments to the International Style of Buddhist art. This realistic style flourished in the late 600’s and 700’s. The full modeling of the figures and the lotus throne reveal the importance of Buddhism for east Asian sculpture. Other artists used the values of Confucianism as inspiration for creating statues.

Japan.

The Jomon, an early Japanese culture of the Neolithic Period, made expressive vessels and figurative sculpture in clay. By the A.D. 200’s, Japanese metalworkers cast ritual bells and decorated mirrors in bronze. Sculptors also made clay figures of human beings and animals, called haniwa, as funeral art for members of the ruling classes.

The introduction of Buddhism in the mid-500’s brought the advanced culture of the Asian mainland and a developed sculptural tradition to Japan. The early centuries of Japanese art history reflect a reworking of artistic styles developed in China and Korea. Korean sculptors who moved to Japan produced some of the early masterpieces of Japanese sculpture. One of these sculptors was Tori Busshi, who worked during the early 600’s. Japanese sculpture refined a style developed on the Asian mainland. However, even under the cultural domination of China, Japanese sculptors created works of great sophistication and beauty.

In response to the realism of the International Style of Buddhist art, a new style of Japanese sculpture arose in the 800’s. Sculptors carved images from a single block of wood. The resulting figures emphasized the block from which they were cut. These figures had massive proportions, heavy thighs, thick facial features, and deeply cut drapery.

By late in the Heian period (794-1185), sculptors responded to the current taste for courtly elegance and refinement. The work of the sculptor Jocho and his studio created the model for subsequent Heian period sculpture. Jocho used a new technique of assembled or joined wood-block construction. He created an idealized style of elegant proportions. Other sculptors of the Heian period represented deities of Japan’s traditional Shinto religion in painted wood.

Jocho, who died in 1057, ended the tradition of the anonymous sculptor in Japan. In the succeeding Kamakura period (1185-1333), individual sculptors and their schools became increasingly important. The Kamakura period was the great age of Japanese sculpture. Kamakura sculpture appealed directly to ordinary people and was conservative in style. Portrait sculpture of both real and imaginary subjects, and images of minor deities, exhibit the full power of the new style.

Works by the great Japanese sculptor Unkei, who died in 1223, reveal a realistic technique that characterizes his style. One of Unkei’s masterpieces is his imagined portrait of the Indian holy man Asanga. The statue is also called Muchaku in Japanese. The realistically painted wood is deeply carved to suggest the weight of real fabric. Unkei individualized the figure’s features and emphasized the bone structure and muscles. The tension in the face and hands suggests vitality. See Ivory.

African sculpture

The peoples of Africa have created an immense variety of sculpture. The materials, purpose, and meaning of the sculpture vary according to the peoples’ ways of life and thought. Settled agricultural peoples have a long tradition of sculpture in wood, clay, metal, stone, and ivory. However, nomadic African peoples who live primarily by hunting or keeping herds of animals have created virtually no large sculpture.

Outside of Egypt, the earliest known African sculptures are terra-cotta heads and figures from the Nok civilization in present-day Nigeria. These works date from about 500 B.C. Archaeologists are finding evidence of early sculptural traditions elsewhere in Africa as well.

To Westerners, traditional African sculpture sometimes seems strange and difficult to understand. Until the 1900’s, Western sculpture emphasized realism. Some African sculptors have shared this interest, but most have deliberately distorted form for expressive purposes. It is important to note that African sculptors were not trying to achieve an accurate surface representation of their subject. Instead, they wanted to produce a visual and emotional response, such as respect, fear, or pleasure. Over time, distinctive regional styles developed that emphasized these characteristics.

Because wood, widely used as a material, decays quickly in tropical climates, little African sculpture survives from before the 1800’s. At that time, European missionaries and colonizers recorded aspects of traditional African life and brought works of art in increasing numbers to the West. The coasts and river basins of the western part of the continent had the most European contact. As a result, the art of these regions is the best known outside of Africa. However, artistic traditions elsewhere in Africa are also highly developed.

Royal and public sculpture.

Certain regions in Africa grew wealthy through trade by about A.D. 1000, and complex societies developed that included kingship and elaborate court life. By the 1400’s, vast empires south of the Sahara had prospered from control of gold, ivory, and other precious materials. Artists made sculptures, as well as other art forms, to represent and enhance the authority of kings. Their works included portraits of rulers, accounts of mythical or historical episodes, and highly decorative thrones that are closer to sculpture than to furniture. An example is the Royal throne from the palace at Foumban in Cameroon.

Today, some African sculpture still is made for public display. Some works play important religious and social roles. For example, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kongo people and their neighbors seal oaths and settle legal disputes by driving blades or nails into a large male figure. This figure, called a nkisi, is the residence of powerful spirits. Over time, such a figure becomes a kind of historical record for its village. The materials, facial expression, and pose of nkisi figures show their power.

African dance masks are also made for public display. In the Western world, such masks are generally hung on a wall and admired for their form. In Africa, however, the mask is one of several elements in a dance costume and is usually seen in motion. In African villages, masked dancers appear on a number of public occasions. They celebrate harvests, welcome back boys and girls who have gone through religious initiation, and participate in funeral ceremonies. Most masks represent standard characters from myth or folklore. They are widely recognized by the audience. The performance of the dancers is often meant to demonstrate both acceptable and unacceptable behavior, and thus reinforce social and moral values.

People in Igbo villages in Nigeria sometimes build mud sculpture displays called mbari houses as a way to educate young people and remind everyone of common Igbo cultural expectations. Inside each house are dozens of brightly painted figures, many of them life-sized. They show scenes of normal life next to mythic, outrageous, or sexually explicit images. The displays have a moral purpose. They tell stories in which the good are rewarded and those who behave in an unacceptable way are punished.

Personal sculpture.

African artists also make much sculpture for the everyday use of common people. Sculptors often create such useful objects as cosmetics boxes and combs. They even carve decorative geometric designs and tiny animals or human figures on pulleys that are part of weaving looms.

Some personal sculpture has a religious purpose, sometimes to commemorate a death. Twin births occur frequently among the Yoruba of Nigeria. If a Yoruba woman gives birth to twins and one baby dies, she cares for a small wooden figure in memory of the loss. These figures, called ere ibeji, are a well-known form of African art in the non-African world. Men in Gabon keep the bones of ancestors in a basket or box guarded by a spirit figure or highly abstract head, often made of wood and covered with metal. Ijaw people of Nigeria remember their ancestors with an elaborate three-dimensional memorial screen that depicts the deceased.

African sculpture today.

Male artists still make most African sculpture, both for traditional uses and to sell to tourists. The artists learn their skills through an apprenticeship system. They study with an older sculptor until they master the techniques of their art. During the European colonial period, Western ideas about education were introduced into Africa. Many African schools and universities now provide art education similar to that in Europe and North America. As a result, many studio-trained artists, both male and female, produce work more closely resembling that of Western artists. However, the African sculptors often incorporate traditional images or themes into their works.

Pacific Islands sculpture

Artists of the Pacific Islands have produced sculpture in an astonishing variety of materials. These materials include wood, wicker, stone, ceramics, barkcloth, tortoise shell, dog’s teeth, and cobwebs. Many kinds of Pacific sculpture have undergone change in the last 100 years as European tools and materials became available to sculptors, and as ways of life altered.

Pacific artists frequently make the human form their subject. However, they are generally not concerned with producing a realistically proportioned or modeled image. They are even less interested in creating portraits of individuals. For the most part, sculpted figures represent supernatural beings, such as spirits, deities, or deceased ancestors. Thus a close copying of human anatomy is not the artist’s goal. The expressive qualities of the sculpture are of far greater significance. The Pacific Islands are grouped into three main regions: Micronesia, Polynesia, and Melanesia.

Micronesia.

In the tiny scattered islands of Micronesia, people have not made much three-dimensional art. However, in the central region of the Caroline Islands, artists made masks and massive, highly abstract wooden figures until the early 1900’s.

Polynesia

has developed a great number of sculptural traditions. In earlier times, the region had dense population centers and highly developed political and religious leadership. As a result, a specialized class of artists emerged. Much of their work was meant to demonstrate the rank and status of their patrons.

Before the arrival of Christian missionaries, Hawaiian temples were filled with heads and figures, often more than 6 feet (1.8 meters) high. They were made of wicker or wood and represented deities. Some were ornamented with feathers, teeth, or shells. Artists also made smaller sculptures and decorative arts, such as cooking utensils, in a similar style. These pieces showed a shortened body and dramatic grimacing face.

Māori sculpture of New Zealand ranges in size from large carved architectural panels for assembly houses to small jade pendants called hei tiki. Māori religious tradition placed many restrictions on the making and use of sculpture. As a result, artists had to be highly educated in religious as well as artistic ideas. Scholars believe most figures represent honored ancestors. Lively curved surface decorations reproduce patterns formerly tattooed on the skin.

Melanesia

is one of the most culturally diverse regions in the world, and this diversity is reflected in its art. Melanesian sculptors, primarily men, make human figures, mythical beings, and animals. They also produce masks for occasions ranging from harvest festivals to funerals and initiation ceremonies. Some sculptures are made for public display. But others are kept inside houses that are forbidden to anyone but initiated males. For example, in many villages along the Sepik River in New Guinea, men make large wooden figures for public view. They also carve smaller ceremonial objects, as well as drums, canoe prows, and large decorated hooks for storing food and possessions inside houses.

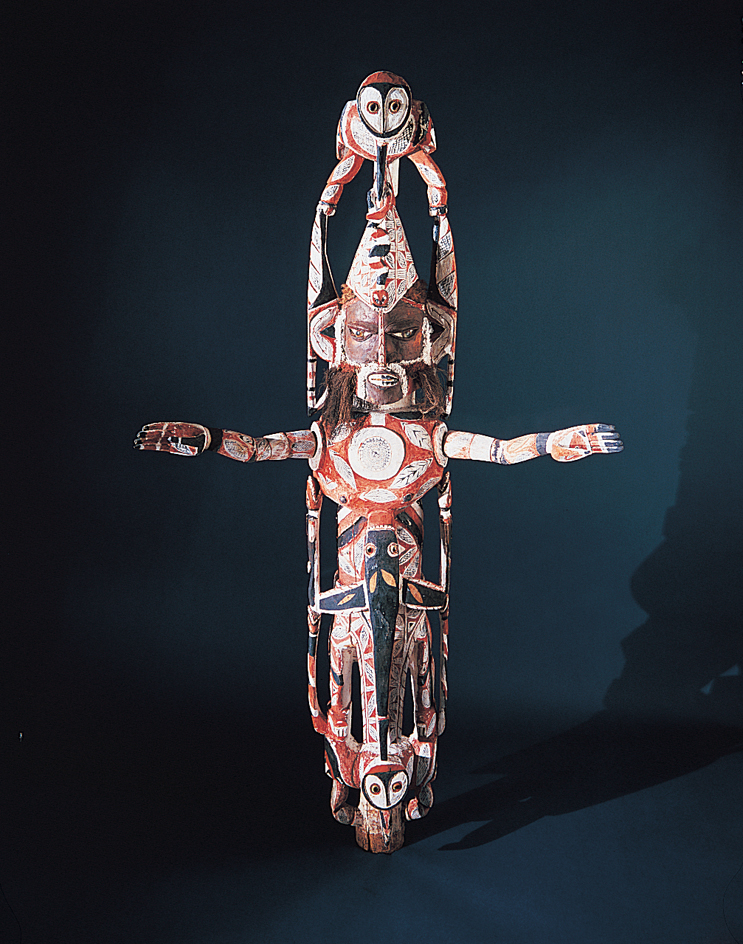

In many regions of Melanesia, public sculpture is thought of much as it is in the West. Works are commissioned by patrons, and artists are widely known by name. On the island of New Ireland, in Papua New Guinea, families commission sculpture groups at great expense for memorial ceremonies called malagans. The sculptures are complex combinations of images of human beings, animals, and dazzling patterns that have profound meanings. The display is arranged, discussed, and admired, but then the works—also called malagans—are discarded and allowed to decay. The right to make a particular sculpture can be inherited or sold. Because the owners remember its appearance, they can commission a new version for special occasions.

Indian sculpture of the Americas

Knowledge of the sculptural traditions of American Indians will always be incomplete. In many regions, Native American sculptors worked mainly in wood and other perishable materials, which disintegrate over time. Even sculptures made of durable materials have been destroyed by forces of nature or human activity. Because looters often plunder archaeological sites, the primary source for information, scholars may have difficulty determining the age and origin of surviving objects. In spite of so much missing evidence, however, it is still possible to form a general picture of the Indian sculpture of North, Central, and South America.

Early sculpture.

Although people in the Americas created sculpture earlier, the oldest well-defined sculptural traditions known thus far are those of the Olmec and the Chavin. The Olmec people lived in Mexico, and the Chavin culture thrived in Peru. Both cultures developed in the centuries before 1000 B.C. They emerged with the development of agriculture, the beginnings of towns and cities, and the rise of specialists in art and religion.

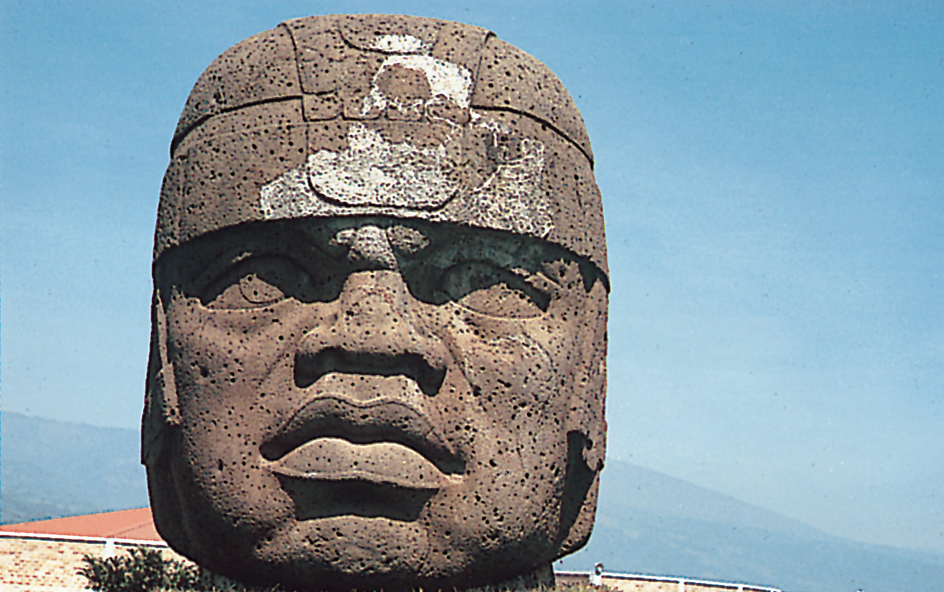

Olmec artists produced human figures in ceramic and jade. Many of these works show the facial features of the jaguar, an animal that often appears in Mexican and Central American art. The Olmec also made a variety of architectural sculpture, such as reliefs on buildings that show human and religious subjects. Perhaps the most spectacular Olmec works were their colossal stone heads, which historians assume had religious significance.

Chavin art, though smaller in scale than Olmec works, shows a similar high level of technical accomplishment. A Chavin Vessel in the form of a jaguar is an example. In addition to works in stone, ceramics, and shell, Chavin artists also sculpted in gold.

About the time when Olmec and Chavin art was developing, a tradition of sculpture was forming farther north. In the southern Mississippi Valley and eastward, Indians produced small stone sculptures that archaeologists call bannerstones and birdstones. The stones are weights for a device called an atlatl that permits a spear to be thrown a greater distance. However, most of them show little signs of use. The objects were probably made to display the prestige of their owner, to be exchanged, or to honor the dead.

Later Indian sculpture.

Although Native Americans seem to have made small-scale sculpture in clay continuously throughout much of Central and South America, more ambitious traditions developed with the rise of cities. In urban areas, artists most often worked in the service of political or religious authorities. The Maya succeeded the Olmec in southern Mexico and Guatemala. The Maya continued the production of large-scale stone architectural sculpture. They erected stelae in their city plazas to commemorate Maya rulers or deities or historical events and ceremonies. Maya artists also made smaller items in jade, stone, and ceramics.

In what is now Costa Rica and Nicaragua, artists produced sculptures in many materials—ceramics, cast and hammered gold, jade, and stone. Among their most spectacular creations are stone sculptures in the form of metates (corn-grinding platforms). Indians throughout Central and South America made and used simple stone metates. The platforms continue in use today. However, many elaborate versions show no signs of wear. They may have served as symbols of authority, indicating control of the process of transforming corn into food.

In Peru, artistic expression flourished most dramatically in ceramics, principally in spherical pots that often were made in human or animal form. Most were apparently made as grave goods, which were items buried with a dead person. Some of the more complex examples were formed in clay molds. The most famous of these are the Moche portrait jars from the northern coastal area, depicting detailed faces or crouching figures.

The west coast of Mexico was home to another highly developed tradition of ceramic sculpture. From about 300 B.C. to A.D. 200, sculptors produced a large number of pottery figures for use as grave goods. The sculptures portray human beings, animals, and even vegetables, as well as scenes of figures in houses or performing ceremonial dances. These pieces provide much information about clothing and ways of life. Some of their stylistic characteristics—such as extremely short, thick legs—were determined by the technical requirements of making large ceramic pieces.

Increasing trade and contact throughout the Americas helped the development of urban centers outside Central America. In south and southeastern North America, towns and cities began to develop, especially in the southern Mississippi River Valley. These urban areas were never as large or as wealthy as the great cities of Mexico or Peru. As a result, they did not produce the ambitious architectural sculpture of the southern regions. However, artists did work on a smaller scale in wood, stone, clay, and metal. Much of their work, such as representations of human heads and figures, probably had religious or political purposes. Some sculpture, such as pipes, was made for personal use.

The European impact.

The arrival of Europeans at the end of the 1400’s brought catastrophic change to the lives of the original inhabitants of the Americas. Many Indians died in battles or from diseases the Europeans introduced. In Central and South America, earlier forms of social organization were replaced by Spanish colonial rule and especially by the influence of the Roman Catholic Church.

The Europeans suppressed or destroyed many local artistic and religious traditions, but others evolved into new forms. For example, Indians in Mexico wore masks in ceremonies. These ceremonies were transformed into the festivals of the Christian church calendar. Wooden masks, which are still made in many Mexican towns, combine ancient elements with images of saints or Biblical characters.

In what is now the United States, the experience of Native Americans in dealing with Europeans was more varied. In the Southwest, Indian religious traditions survived best among remote or culturally closely knit peoples such as the Pueblo Indians. They included the Zuni of New Mexico and the Hopi of Arizona. Pueblo sculptors make the well-known Kachina dolls. These dolls are actually models of spirits called Kachinas in ceremonial dance costumes. The dolls are made for their original purpose of teaching children about Kachinas. Artists also sell the dolls to outsiders. See Kachina with its list of related articles.

The Indians of the eastern coast of North America lost much of their traditional way of life after Europeans arrived. Colonists from northern Europe constantly forced the northeastern Indians westward, with little regard for their survival. As a result, much of their culture has been lost. Scholars do know that in precolonial times people of the Eastern Woodlands made pipes and small figures of stone and clay. They also carved wood, but little has survived. Notable exceptions are the religious masks in wood or twined fiber made by the Iroquois Indians in New York. The masks represent supernatural beings and are used in healing ceremonies.

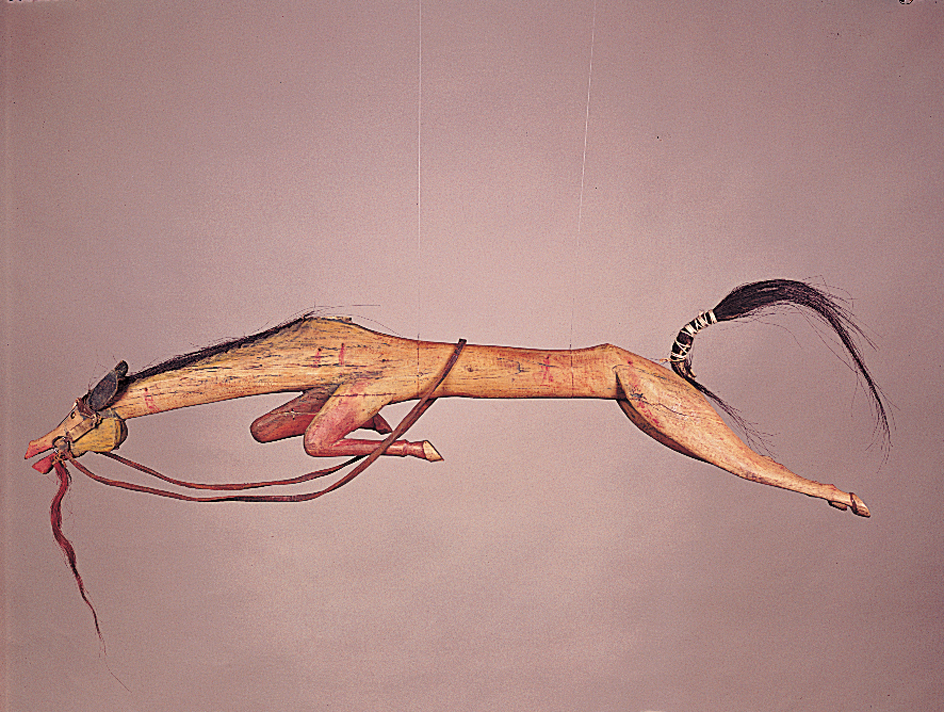

In the center of North America, the Plains Indians retained more of their cultural traditions. However, their nomadic way of life made only small sculptures practical. In Plains religions, the pipe is a sacred instrument. Plainsmen made pipe bowls from stone or wood. By the 1800’s, they often adorned these bowls with elaborate figures. The wooden pipestems were often decorated in high relief, pierced with patterns, or carved in twisted forms. Most Plains sculpture was created in wood, such as the Dance stick carved in the form of a galloping horse used in ceremonial dances. Other sculptures included feast bowls, spoons decorated with animal motifs, and elegant flutes that ended in bird heads.

The Indians of the Northwest Coast of North America have perhaps the most elaborate sculptural tradition. There, wealthy families commission a wide variety of objects, including carved spoons and enormous totem poles, to enhance their prestige (see Totem). Virtually every work of art of the Northwest Coast peoples includes animal themes that refer to mythical stories and clan identity. Many carvings are painted, and some are inlaid with bits of shell or metal. During long winter nights, masked and costumed dancers present elaborate theatrical productions. Many dancers wear transformation masks that can be opened, spread out, or changed from one character to another. Loading the player...

Totem pole

On the Northwest Coast and elsewhere, many Indian artists are working to preserve their culture. They make objects in the traditional way. Other artists, however, acknowledge that their world has changed, and they reflect that development in their work. It might be a relatively small change, such as using commercial paint instead of natural pigments. It also may be a major change, such as making tiny sculptured boxes in precious metals instead of the traditional large carved wooden chests. Some Indian artists produce work that cannot be distinguished from that of other modern artists in Europe and the Americas.

Greek sculpture

Early Greek sculptors made simple, formal works. They gradually learned to make realistic figures and to indicate emotion by facial expression or bodily pose. This was the style copied by Roman sculptors and relearned by Renaissance sculptors. It served as the basic style for European sculpture until the late 1800’s. Loading the player...

Winged Victory

There were three major periods in the development of Greek art: The Archaic period dated from about 630 to about 480 B.C. The Classical period lasted until about 323 B.C. The Hellenistic period ended about 146 B.C.

Archaic sculpture.

In the 700’s B.C., before the Archaic period, artists knew how to make only small figures of clay or bronze. However, they also may have carved wooden statues. During the 600’s B.C., they began making clay figures in molds. The Greeks learned this technique from the Phoenicians and other peoples of the East. Archaic sculptors developed a rigid and Eastern-looking style called Dedalic. They also used this style in carving small limestone figures.

At the end of the 600’s B.C., the Greeks learned from the Egyptians how to make larger statues and how to carve harder stone—their own white marble. From then until about 480 B.C., the Greeks perfected their carving techniques. They gradually succeeded in making figures that were more lifelike. They carved many standing figures of naked male youths. These figures, called kouroi, served as attendants to the temple of a god, or as memorials over tombs. Similar carvings of clothed maidens were called korai. The frontal pose and calm expression of the Kore show how much the Greeks improved on Egyptian work. Livelier figures appeared in reliefs on temples and treasuries, as in the Battle of the gods and giants.

Classical sculpture.

After Greek sculptors learned to show the human body accurately, they paid more attention to drapery. In early classical works, drapery hung straight and rather stiffly, as in the Charioteer of Delphi. In later works in the period, the garments hung in deeply cut folds. Finally, classical Greek sculptors showed drapery clinging to the body or blowing free from it.

The Greeks thought of their gods as being like people. Sculptors portrayed gods as people in such works as the Apollo Belvedere. They showed people as godlike beings. Even after sculptors began to make portraits of real persons, they idealized the faces.

The high point of the classical style is generally considered to be the sculptures on the Parthenon in Athens. They were created after the mid-400’s B.C. These sculptures celebrated the city’s pride and the Greeks’ defeat of the Persians in 480 and 479 B.C.

During the 300’s B.C., sculptures of the human figure showed some emotion and vigorous action. For the first time, some sculptors’ artwork showed goddesses nude. Lysippus made heavily built figures of athletes. Praxiteles specialized in a softer, flowing style in his figures of gods and goddesses. Sculptors decorated sarcophagi (stone coffins) with reliefs. A good example of such a relief is the Alexander Sarcophagus. Portrait sculpture also began during the classical period. Lysippus was perhaps the first to draw the viewer closer to the work of art by making movement in the piece more complex.

Hellenistic sculpture.

The conquests of Alexander the Great carried Greek culture into Egypt and the lands of the East. After Alexander’s death in 323 B.C., his empire was split into smaller kingdoms. In these kingdoms, the courts encouraged local schools of art. The most important of these schools were at Rhodes, Pergamum, and Alexandria. Artists blended local ideas with Greek standards of beauty. The result was a colorful art called Hellenistic.

Athenian artists continued to follow a more classical style. But Hellenistic sculptors preferred to create works in active, dramatic poses. Some subjects were portrayed showing violent feelings and lifelike actions. Many Hellenistic figures were much less idealistic than were earlier works. For example, in the Statue of a seated boxer, the sculptor showed a boxer’s broken nose. For more information about Greek sculpture, see Elgin Marbles; Lysippus; Parthenon; Phidias; Praxiteles; Venus de Milo; Winged Victory.

Etruscan and Roman sculpture

Etruscan sculpture.

The Etruscans probably came from what is now Turkey. They migrated to Etruria (present-day Tuscany, Umbria, and Latium) in central Italy about 800 B.C. They learned sculpture from Greek artists who settled in Etruria, and from Greeks living in neighboring colonies in southern Italy and Sicily.

The Etruscans specialized in bronzes and in terra-cotta works, which they painted in bright colors. Some of the best Etruscan terra-cotta sculptures are four life-sized statues, including one of the god Apollo. These statues stood on the roof of a temple at the ancient Etruscan city of Veii northwest of Rome. Sculptors seldom achieve figures of this size in clay, even today.

Etruscan sculptors also carved works from a soft, porous limestone called tufa. These works included statues and carvings found in tombs and reliefs that decorated boxes containing the ashes of the dead. The Etruscans showed a fondness for gruesome figures, and for portraiture, especially portraits of ancestors. However, Etruscan artists gradually adopted classical Greek styles in sculpture.

Roman sculpture.

The earliest Roman sculpture was influenced by the Etruscans to the north of Rome and by Greek colonists to the south. After the Romans conquered Greece and the Hellenistic kingdoms during the 140’s B.C., they brought hundreds of Greek statues to Italy. They also encouraged Greek artists to work for Roman patrons.

Greek artists brought to Italy the fully developed Hellenistic style, especially that of Alexandria. From 100 B.C. to A.D. 100, artists produced many works in a Greek style that at the same time expressed Roman ideas.

The Romans were religious and created many richly carved altars. Most altar reliefs showed ceremonies or symbolic stories. A famous example is the Altar of Peace in Rome. It celebrated the peace brought to the empire by Emperor Augustus.

The Romans were also particularly interested in showing historical events, a theme that the Greeks had avoided. Reliefs on commemorative arches and columns tell the story of military campaigns. The best-known columns are Trajan’s Column and the Column of Marcus Aurelius. Both show the Romans battling foreign peoples.

Relief decoration on coffins was more Greek than Roman in style and subject matter. However, many reliefs symbolized Roman and, later, Christian ideas about death.

Medieval sculpture

Medieval sculpture had no definite beginning date. It emerged from the tradition of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture that gradually had become fragmented and technically inferior after the A.D. 200’s. Medieval sculpture developed into an artistic tradition in its own right about A.D. 800. This was largely due to the cultural patronage of the great ruler Charlemagne.

Charlemagne conquered most of the area that is now France, Germany, and Italy. To stabilize this vast empire, he encouraged education for the aristocracy and founded a permanent capital at Aachen, Germany. He established centers of learning in royal monasteries and in his imperial court. Those centers also produced art.

Early medieval sculpture.

Carolingian art, named after Charlemagne’s family, extended from the late 700’s through the 800’s. Workshops attached to monasteries produced most surviving sculpture of this time. As a result, artistic production was largely religious, and chiefly applied to objects used in Christian worship services. Carolingian artists created sculpture for covers of Bibles, as decoration for parts of church altars, and for crucifixes and giant candlesticks placed on altars. Lacking other models, sculptors imitated miniatures painted on religious manuscripts.

Most Carolingian sculptures were reliefs. Some told stories, while others promoted ideas. Storytelling scenes were done in a generally realistic style. The gold and silver Altar frontal was made about 835 for the Church of Sant’ Ambrogio in Milan, Italy. The relief portrays an early event in the career of Saint Ambrose, his appointment as consul general of Milan. The figures interact with each other in a believable manner within the shallow space of an abbreviated landscape.

A contrasting style of images is represented by the Aachen situla, made about 1000. This jeweled ivory bucket was meant to hold holy water that was sprinkled by a bishop in solemn processions. The artist endowed the rows of rulers, saints, and guardians with a timeless sacred quality by presenting them unrealistically in a static frontal pose. At the same time, the precious materials of the bucket certified the spiritually cleansing value of the water.

The purpose of the Aachen situla typified the spread of liturgical items that developed with the elaboration of the worship service beginning in the late 800’s. The expansion of the liturgy led to the creation of many objects, such as bishops’ crosiers (staffs), vessels called pyxes to hold Communion wafers, and containers called reliquaries to hold the body parts of saints.

The 1000’s.

The use of relief to decorate small religious objects continued throughout the Middle Ages. But after 1000, sculptors also began to produce larger-scale church furnishings. For example, artists used cast bronze to make monumental doors, candelabra, baptismal fonts, and tomb slabs. By 1100, sculptors also began to make marble furnishings, recalling the grandeur of ancient Rome. The Bari throne in Bari, Italy, may have been created for a meeting of Pope Urban II and church leaders in 1098. The throne extends the tradition of working in precious metals to stone carving, with figures sometimes cut virtually in the round. Other marble furnishings with relief images include pulpits, choir railings, shrines, and table altars.

During the 1000’s, architectural sculpture began a renewal. In the next 100 years, it became the principal area of medieval sculptural achievement. The capital (top of a column) from the church of St.-Benoit-sur-Loire in France has been dated as early as the 1020’s. It may be one of the earliest medieval examples of figurative stone sculpture conceived in high relief. The sculpture represents the flight into Egypt of Joseph, the Virgin Mary, and the infant Jesus. The carving is skillful, but the figures are crudely portrayed. The work was carved by a mason from an architectural workshop instead of a monk from a monastery studio. The work thus marked the appearance of sculpture as a new artistic profession for artisans (craftworkers) outside monasteries.

The peak of architectural sculpture.

With the Tympanum of the central portal of Vezelay Abbey in the 1120’s, architectural sculpture was in its period of greatest creativity. The portal represents an intricate and subtle image of the feast of the Pentecost. Pentecost was the day when the apostles reported that the Holy Spirit had entered into them. The agitated figures of Jesus and the apostles are draped in swirls of garment folds to convey an otherworldly spirituality through their powerful expressiveness. The portal marks the extension of sculptured decoration to the public area of churches. With such works, sculptors established that images could be employed to proclaim complex theological concepts.

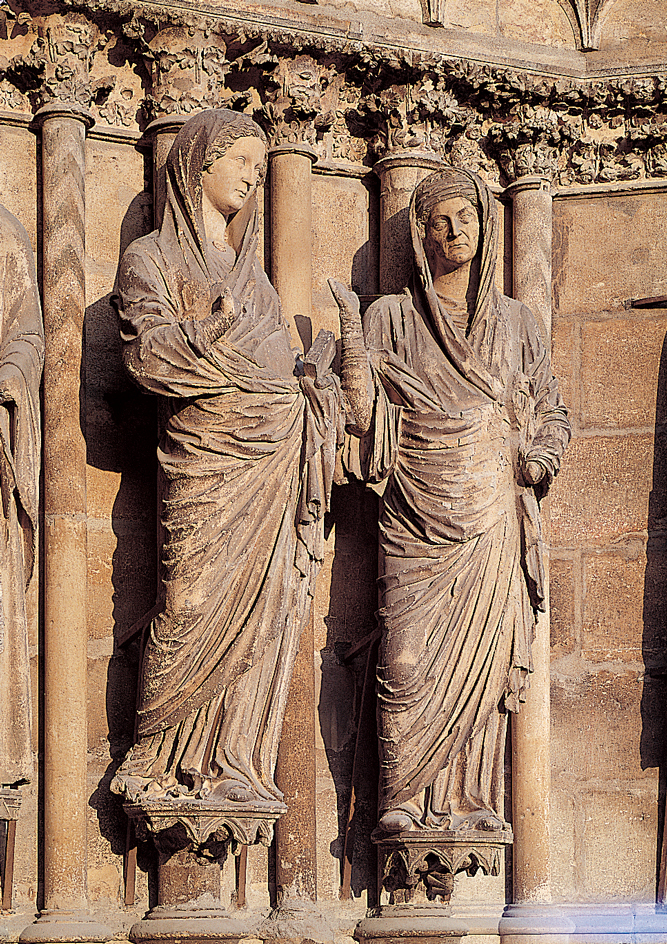

The Visitation group on the west-central portal of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Reims, France, was carved 100 years after the Vezelay portal. The sculptor portrayed the Virgin Mary and Saint Elizabeth. This work represents a completely different approach to sculptured imagery from the Vezelay portal. The figures are larger than life-sized and lifelike in appearance. The sculptor created them with believable proportions and anatomy. The sculptor also used different textures for the hair, skin, and fabric. As a result, the viewer could regard the scene as a living vision, knowing all along that the figures are made of stone.

The different styles of the two portals represent a fundamental change in the nature and function of images. The frank artificiality of Vezelay contrasts with the lifelike illusion of Reims. But both conceptions were prompted by the conviction that images could promote spirituality by vividly representing sacred truths.

Later medieval sculpture.

Patrons and sculptors of the 1300’s and 1400’s turned sharply away from the preoccupations of their predecessors. In the 1100’s and 1200’s, sculptured portals had displayed in public a visual interpretation of religious truths. Late medieval sculpture primarily reflected or stimulated the religious devotion of the individual.

The chief artistic concern in late medieval sculpture was the free-standing devotional statue. These statues were not displayed on main altars. They stood to the side or at the entrance of a lesser chapel. There the statue served as the focus for private prayers and the burning of devotional candles. For more than 200 years, no theme could rival that of the Virgin Mary in popularity. She was usually represented standing and holding the infant Jesus. Worshipers asked Mary to forward their prayers to heaven and to plead with God for special help.

See Carolingian art; Gothic art; Romanesque architecture; Cathedral; Milan Cathedral; Notre Dame, Cathedral of; Architecture (Gothic architecture).

Italian Renaissance sculpture

Figures made by medieval sculptors of northern Europe represented types rather than individuals, such as the concept of a “good man.” But Italian Renaissance sculptors portrayed individual persons—for example, a particular man or woman who was good.

Renaissance sculpture reflected the new outlook on life that first appeared in Italy during the early 1300’s. This outlook, which later scholars termed humanism, emphasized the importance of human beings and their activities. Humanism had its roots in the civilizations of ancient Greece and Rome. The Renaissance was given its name, which means rebirth, because of the revival of interest in classical art, architecture, and civilization. Artists and scholars, especially in Italy, wanted to recapture the spirit of the Greek and Roman cultures in their own art, literature, and philosophy. For more information about this rebirth of interest in classical culture, see Humanism; Renaissance.

In the late 1200’s, Nicola Pisano and his son Giovanni began the revolutionary changes that led up to the Renaissance in Italian sculpture. They were architects and designers as well as sculptors. Both are noted for their reliefs and ornamentation on pulpits. The Massacre of the Innocents by Giovanni Pisano is an example. The dense composition of this relief shows that the sculptor was inspired by the carved Roman coffins called sarcophagi. Its content, in which each person reacts as an individual, shows the new attitude of the Renaissance. The actual carving remains in the medieval Gothic style, however.

During the 1300’s, political and economic troubles in Italy limited sculptural activity. But the great revival of art in Florence about 1400 brought two generations of sculptors who were the equals of any artists anywhere at any time. They returned to classical Mediterranean traditions and turned away from the Gothic style, which was more at home in northern Europe.

Early Renaissance.

The greatest sculptor of the early Renaissance was Donatello. By 1409, he had produced a stone statue of David which, though Biblical in subject matter, was entirely new in spirit—the portrait of a proud, triumphant boy. In another statue of David, a bronze completed about 1430, Donatello revived the use of the nude figure. This statue reestablished the classical idea of beauty—the naked human body.

The new naturalness quickly affected sculpture throughout Italy. Donatello decorated the pulpits and singing galleries of churches in Florence and Padua with merry putti (singing and dancing children). Luca della Robbia made popular colored terra-cotta figures that were copied for generations. Sculptors also began to make figures of the Virgin Mary whose models might have been local women. These sculptures differed greatly from the formal, impersonal Romanesque and Gothic types.

Other new forms of sculpture developed during the 1400’s. They included lifelike portrait busts and great monuments in the classical style. Desiderio da Settignano became famous for portraits. Among the other brilliant sculptors of the 1400’s were Jacopo della Quercia, Michelozzo Michelozzi, Bernardo and Antonio Rossellino, and Agostino di Duccio.

In the mid-1400’s, Donatello moved to Padua. His style of modeling became more precise and sharp, and influenced the whole trend of sculpture in northern Italy. Many sculptors were influenced by this new style. Among them were the Mantegazza brothers, Giovanni Amadeo, the Lombardi family, and the great bronze worker Andrea Briosco, who was called Il Riccio. They all showed rather stylized, flattened planes in their works. Only in later nonreligious works, such as small bronzes and medals, did sculptors return to rounder, classical forms.

Two important sculptors of the late 1400’s were Antonio del Pollaiuolo and Andrea del Verrocchio, both of Florence. Pollaiuolo, like Donatello and many other artists of this period, made a careful study of the appearance of muscles while the body is in motion. These artists caught fleeting moments of tense action in their poses. Verrocchio designed the powerful realistic portrait of the Renaissance political and cultural leader Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Michelangelo.

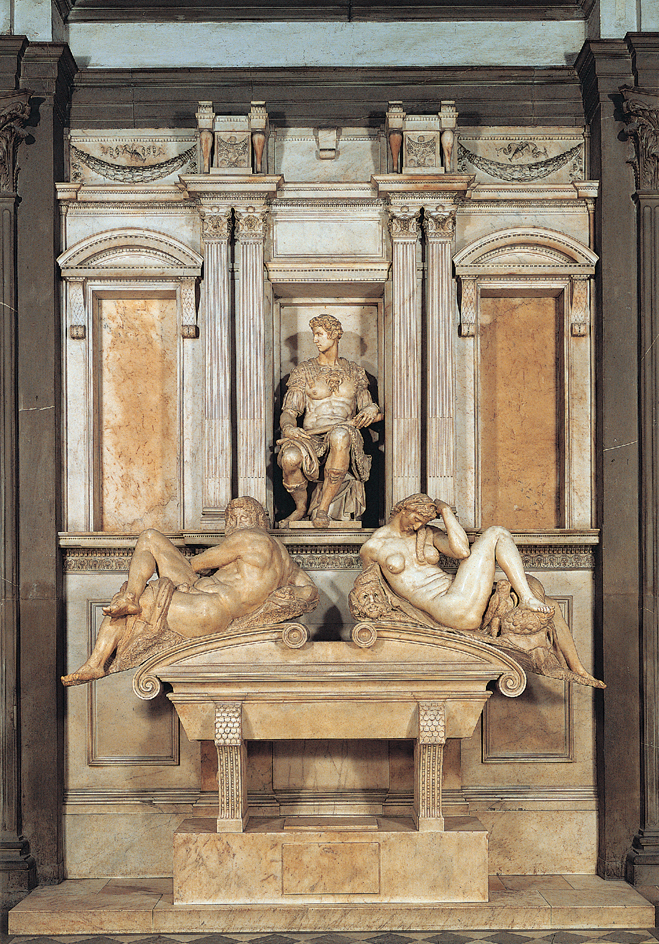

The great flood of Italian genius crested in the early 1500’s in Michelangelo Buonarroti. His great brooding sculptures, including the figures of Night and Day on the Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici in Florence, carry the observer beyond earthly reality. The deep feeling and emotion of his figures set them apart from all other sculpture of that time.

Most other sculptors of the 1500’s produced rather forced adaptations of imperial Roman figures and groups. Some monumental dignity can be seen in the works of such Venetian sculptors as Jacopo Sansovino and Alessandro Vittoria. Other sculptors followed Giambologna’s experiments in composition in which figures turn and twist in complicated poses. Still others, including Benvenuto Cellini and Bartolommeo Ammannati, developed the Mannerist style (see Mannerism). This style emphasized grace and elegance, and resulted in the creation of slender, artificial figures. An example is Cellini’s bronze Statue of Perseus. For more information on Italian Renaissance sculpture, see Ghiberti, Lorenzo; Pisano, Giovanni; Pisano, Nicola.

Sculpture from 1600 to 1900

European sculpture.

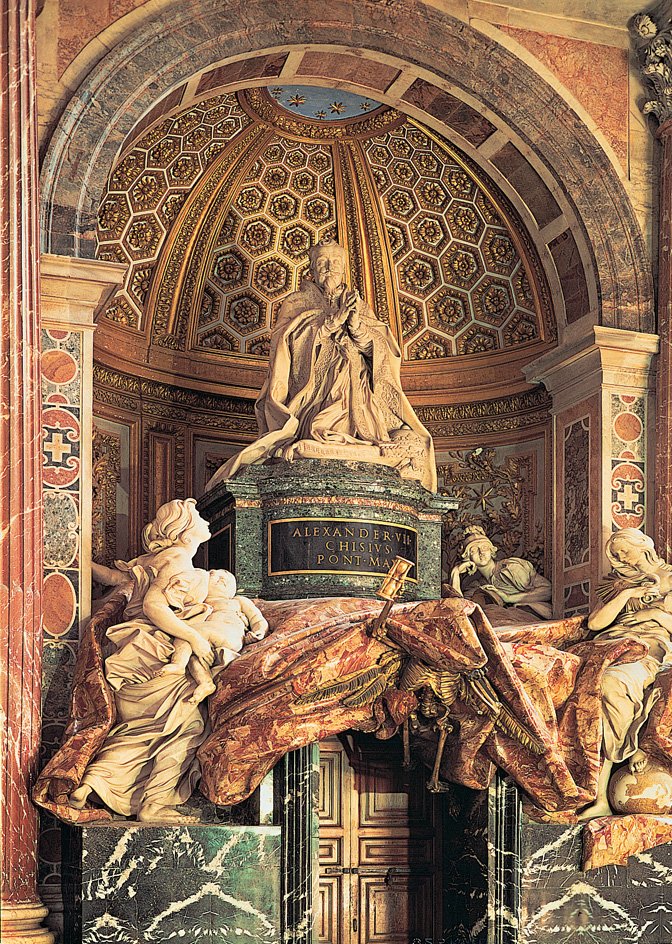

The greatest master of European sculpture in the 1600’s was Gian Lorenzo Bernini of Italy. Bernini was a superlative craftsman and also an outstanding architect. His sculpture for the Tomb of Pope Alexander VII shows the wide range of his talent. The work is typical of the Baroque style of the period because it was designed to appeal primarily to the emotions and senses. Bernini combined emotional and sensual freedom with theatrical presentation and an almost photographic naturalism. Bernini’s saints and other figures seem to sit, stand, and move as living people—and the viewer becomes part of the scene. This involvement of the spectator is a basic characteristic of Baroque sculpture.

The sculptors who succeeded Bernini in Rome during the late 1600’s softened the dynamic and showy Baroque style. They used a more static and restrained Classical style. These artists were technically skilled and made hundreds of monuments that filled the churches of the time. By the early 1700’s, they had become more interested in technical skill than in content. Their art reflected the change. But these artists had an important influence on sculptors of France and Flanders who made up the Franco-Flemish school.

Franco-Flemish sculptors were responsible for many church and public monuments built in northern Europe during the 1700’s. Their sculptures decorated many royal palaces and gardens, including Versailles in France. These artists all followed the same style. They combined naturalistic details with artificial poses and gestures, as shown in Antoine Coysevox’s statue of Mercury.

A brilliant new movement called Rococo grew up in Germany during the early 1700’s. The movement was led by such artists as Ignaz Gunther and Ferdinand Dietz. Their works are dramatic, colorful, and technically superb. Rococo saints and goddesses mingle in architecture with plasterwork and painted ceilings to create an extraordinary world of fantasy.

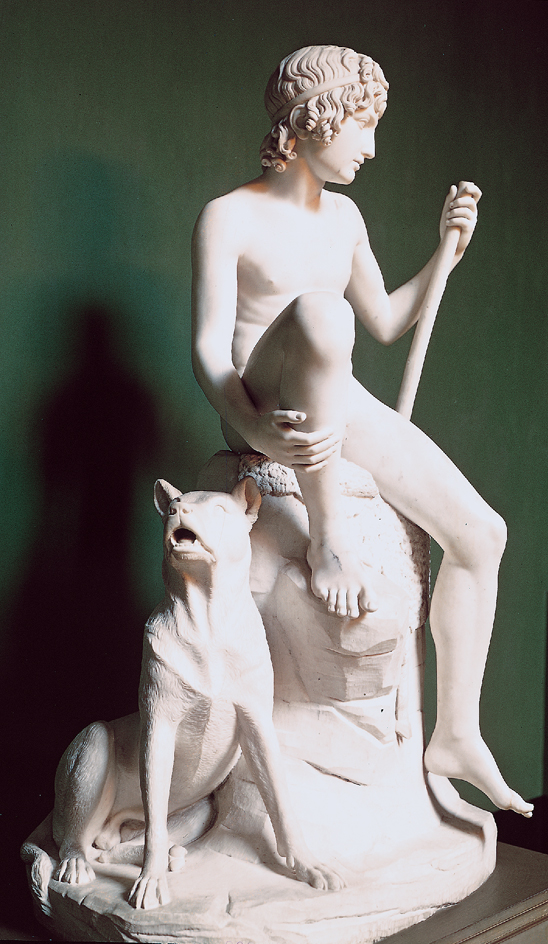

The neoclassical movement arose in the late 1700’s. The members of this vast international school restored what they regarded as classical principles of art. They were direct imitators of ancient Greek sculptors. They emphasized classical drapery and the nude. Leading neoclassical sculptors included Antonio Canova of Italy, John Flaxman of England, and Bertel Thorvaldsen of Denmark. Thorvaldsen’s delightful marble statue A Shepherd Boy is typical of the neoclassical style. This style greatly influenced churchyard and public monuments.

Jean Antoine Houdon of France was perhaps the greatest European sculptor of the 1700’s. He was known chiefly for his portraits of important men and women in Europe and America. These portraits show Houdon’s ability to capture the personalities of his subjects and his genius at working in a wide variety of materials. The marble statue of the French philosopher Voltaire is one of his best-known works.

The Romantic movement began in the 1830’s and existed side by side with Neoclassicism until about 1900. Romantic sculpture was sentimental, and it appealed to the senses. Leading sculptors who worked in the Romantic style included Francois Rude, Jean Baptiste Carpeaux, and Auguste Rodin, all of France. Such works as Rodin’s Orpheus emphasize the possibilities of the modeler’s technique. Rodin’s technique greatly influenced sculpture of the 1900’s.

American sculpture.

North America had no professional sculptors until the late 1700’s. However, anonymous craftworkers created fine examples of what is called folk art. The Gravestone by Zerubbabel Collins and other gravestones in New England cemeteries reflect Puritan ideals in crude but vigorous reliefs. Many metal weather vanes featured fanciful designs.

In the 1820’s, American sculptors started to go to Italy, where they were greatly influenced by the classical works they saw. Congress commissioned Horatio Greenough to make a colossal marble Statue of George Washington. Greenough represented his subject seated, seminude, in the pose of the Greek god Zeus. Hiram Powers created smooth and impersonal nude mythological figures. He also made some remarkable realistic portrait busts of public men. William Rimmer made a few dramatic, struggling figures. These figures were more emotional, powerful, and tragic than earlier American works. They showed a great knowledge of anatomy and a strong feeling of tension. John Rogers made small groups of American Civil War scenes. Rogers also created works that suggested the pleasant, warm-hearted quality of small-town everyday life.