Sewage is water that contains waste matter produced by human beings. It is also called wastewater. It contains about a tenth of 1 percent solid matter. Sewage comes from the sinks and toilets of homes, restaurants, office buildings, and factories. It contains dissolved material that cannot be seen, plus bits of such solid matter as human waste and ground-up garbage. Some sewage may also contain ground and surface water runoff that occurs after storms or floods. Most sewage also includes harmful chemicals and disease-producing bacteria.

Most sewage eventually flows into lakes, oceans, rivers, or streams. In the United States, almost all sewage is treated in some way before it goes into the waterways as a semiclear liquid called effluent. Untreated sewage looks and smells foul, and it kills fish and aquatic plants.

Even treated sewage can harm water. For example, most methods used to treat sewage convert organic wastes into inorganic compounds called nitrates, phosphates, and sulfates. Some of these compounds may serve as food for algae and cause large growths of these simple aquatic organisms. After algae die, they decay. The decaying process uses up oxygen. If too much oxygen is used, fish and plants in the water will die.

A system of pipes that carries sewage from buildings is called a sanitary sewerage system. There are two main types of sanitary sewerage systems: (1) urban sewerage systems and (2) rural sewerage systems.

Urban sewerage systems

In the United States, treatment of sewage is regulated by the Clean Water Act of 1972 and its amendments. In most U.S. cities and towns, sewage from homes and other buildings flows into a public sewerage system. Many industries operate their own wastewater treatment facilities. Other industries partially treat the sewage and then discharge it into a public sewerage system. In some cases, industrial wastewater flows untreated into waterways.

In a public sewerage system, the largest sewers, called interceptors, carry the sewage to a wastewater treatment plant. Sewage treatment in most cities involves two main steps, primary and secondary treatment. Some cities also require a step called tertiary (third) treatment.

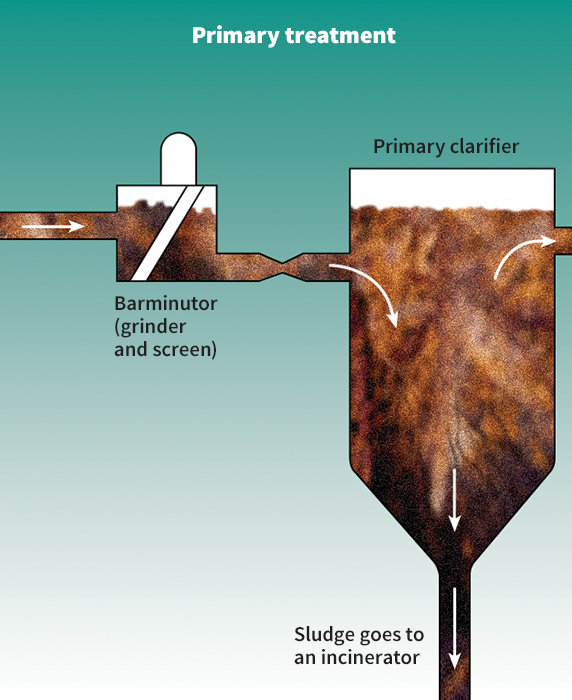

Primary treatment

removes the heaviest solid material from sewage. At a treatment plant, sewage first passes through a screen that traps the largest pieces of matter. It then flows through a grit chamber, where heavy inorganic matter, such as sand, settles. The liquid next flows into a large primary sedimentation tank. Many suspended solids sink to the bottom of this tank and form a muddy material called sludge. Grease floats to the surface, where it is removed by a process called skimming. The effluent is then released into waterways.

Primary treatment removes about half the suspended solids and bacteria in sewage. Sometimes a gas called chlorine is added after primary or secondary treatment to kill most of the remaining bacteria. Primary treatment removes about 30 percent of the organic wastes. When the remaining organic wastes are discharged into waterways, bacteria break them down and thus continue the process of purifying the wastewater. The breaking-down process uses up oxygen in the water. See Water pollution (Effects) .

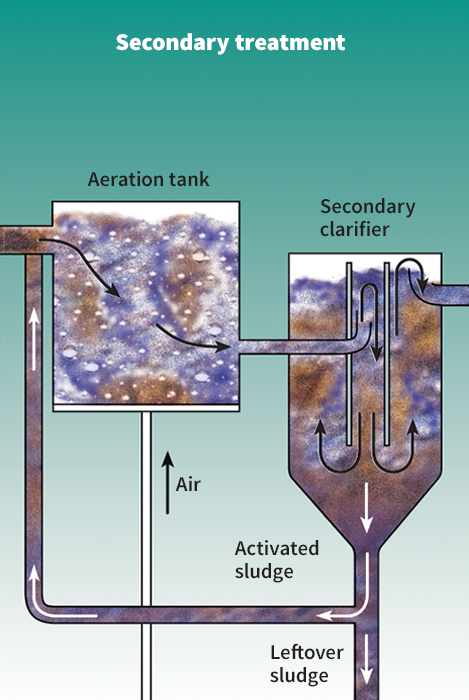

Secondary treatment

removes from 85 to 90 percent of the solids and oxygen-consuming wastes remaining in sewage after it has undergone primary treatment. The most common methods of secondary treatment are (1) the activated sludge process and (2) the trickling filtration process.

The activated sludge process.

In this process, effluent from the primary sedimentation tank flows into a second tank called an aeration tank. Air is injected into this tank in a bubbling action. Sludge containing useful bacteria is also in the tank. The useful bacteria move through the liquid and change the organic matter into less harmful substances. Next the liquid flows into a final sedimentation tank, where the sludge settles to the bottom. The effluent is then discharged into waterways. Part of the sludge is recycled into the aeration tank.

The trickling filtration process.

Trickling filters are tanks filled with crushed rocks. As sewage is distributed over the rocks, it reacts with slime that develops on the rocks. The slime contains useful bacteria that change organic material in the sewage into less harmful substances. These substances are removed in a final sedimentation tank, where they fall to the bottom as sludge.

Sludge resulting from primary and secondary treatment is pumped to a sludge digestion tank. In this tank, bacteria break the sludge down into less harmful substances producing methane gas, a useful fuel. Digested sludge may be dried for use as fertilizer or burned.

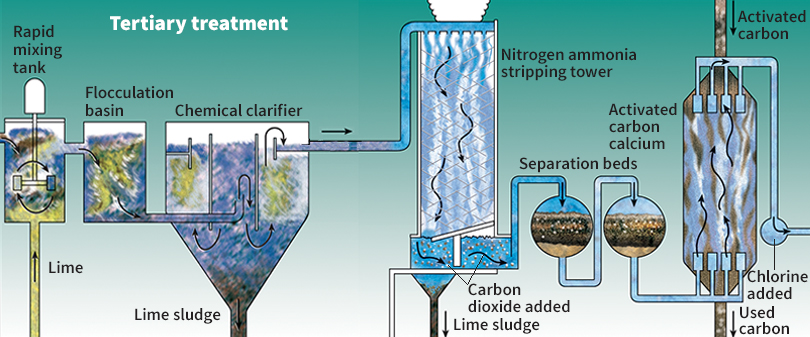

Tertiary treatment

is used after primary and secondary treatment to produce purer effluent. There are various methods of tertiary treatment. The method a community chooses depends on (1) what substances are present in its raw sewage and (2) how the effluent will be used. Tertiary treatment methods include biological nutrient removal, chemical treatment, microscopic screening, radiation treatment, and the discharge of the effluent into lagoons.

Tertiary treatment makes effluent safer to discharge into waterways and safer for industry to use. Few treatment plants in the United States use all three methods of treatment—primary, secondary, and tertiary. However, many states are working with local communities to improve sewage treatment methods.

Rural sewerage systems

Many rural areas are not served by public sewers. In such areas, most homeowners use septic tanks to treat their sewage. These tanks are concrete or steel containers buried underground at homes and buildings.

Sewage flows into a septic tank through a pipe connecting the tank with a building. Solids in the sewage sink to the bottom of the tank as sludge or float to the surface as scum. Effluent then flows from the tank into a leaching field, a system of pipes with open joints that allows sewage effluent to be gradually distributed into the soil. Soil bacteria then destroy the remaining organic material in the effluent.

In a septic tank, bacteria in the sewage attack and digest the sludge and scum. This digestion process changes most of the wastes into gas and a harmless substance called humus. The gas escapes into the air. The humus in the tank must be pumped out periodically and taken to a sewage treatment plant.