Shell is an important feature of many animals and plants. Most shells grow on the outside of living things. These shells are like strong suits of armor that protect the organisms they cover. Clams, turtles, and coconut seeds have outside shells. In cuttlefish and many kinds of squid, the shells grow inside the bodies. Such shells, called cuttlebones in cuttlefish or pens in squids, help support the bodies of the animals.

Some kinds of shells have beautiful shapes and bright colors. Others are plain and colorless. Among the smallest kinds are the shells of vitrinellids, marine snails found in many parts of the world. Some vitrinellid shells grow only about as big as a grain of sand. The largest shell is that of the giant clam of the Indian and southwestern Pacific oceans. It can measure more than 4 feet (1.2 meters) long and weigh about 550 pounds (250 kilograms).

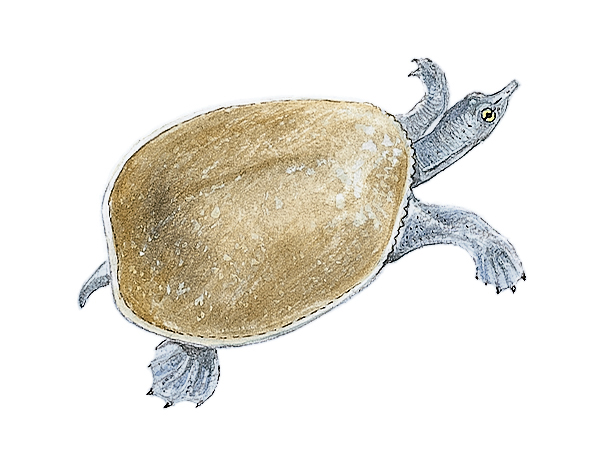

Some kinds of animals begin their lives inside egg shells. Thin, brittle shells cover the eggs of birds. Thick, leathery shells protect the eggs of alligators, snakes, and many other reptiles. Strong, rubbery shells cover the eggs of the platypus and echidna. Many other animals spend all their lives in shells that are important parts of their bodies. The shells of clams and oysters are really the skeletons of these animals. The shells of turtles and tortoises include part of their backbone and ribs.

Many people collect shells as a hobby. Most shells in these collections belong to mollusks, a group of animals that includes clams, conchs, cowries, oysters, and snails.

This article provides general information about mollusk shells in the following sections: Shell (How shells are formed) (Kinds of mollusk shells) (Collecting shells) (Uses of shells). For information about the animals that grow these shells, see the separate World Book article on Mollusk and its list of “Related articles.” For information about other kinds of shells, see the World Book articles on Egg and Seed, and articles on individual plants and animals, such as Walnut and Turtle.

How shells are formed

There are about 100,000 living species of mollusks. Each kind has a shell with its own special design and shape, but all are formed in much the same way. Some mollusks that grow shells live in the ocean, some in fresh water, and others on land.

Many shells consist of three layers—an outer, middle, and inner layer. These layers are also called the prismatic layer (outer layer), the lamellar layer (middle layer), and the nacreous layer (inner layer). Many primitive mollusks have only two layers, a prismatic and a nacreous layer. Each layer contains mineral crystals and an organic mortar holding the crystals together. The crystals consist of calcium carbonate, a kind of lime also found in marble and some other kinds of rocks. The prismatic layer is composed of small, elongated particles called prisms. Nacre or mother-of-pearl often is deposited on the inner shell surface as small six-sided or cookie-shaped tablets. These grow and combine into a smooth, glossy sheet.

The food eaten by a mollusk, and the water or soil it lives in, provides the minerals that form the shell and give it color. The blood stream of the animal carries the minerals to the mantle, a fleshy skinlike tissue that produces the shell. The inner layer of the mantle forms the inner shell layer, and the outer edge of the mantle helps form the middle and outer shell layers. A part of the mantle also produces the periostracum, a thin layer that covers the outer shell. Thinner periostracums are clear while thicker ones are darker. In some species, the periostracum can form hairlike structures on the outside of the shell, giving the mollusk a shaggy appearance.

The pattern of the shell color depends on (1) whether color is added continuously, and (2) the number of places in the mantle from which color is added. For example, if color is added continuously from only one place in the mantle, the shell will have one stripe. If color is added continuously from four places, the shell will have four stripes. If the color flow is interrupted from time to time, spots or bars will form on the shell.

Most kinds of mollusks add material to their shells throughout their lives. As long as the animal grows, its shell also grows. Clams and snails begin to grow shells before they hatch. After they leave the egg, their bodies rapidly increase in size. A sea snail that is only 1/10 inch (3 millimeters) long when it hatches may grow 5 or 6 inches (13 or 15 centimeters) in six months. Most clams and sea snails grow for about six years, though some may reach 100 years of age.

Kinds of mollusk shells

Mollusk shells can be divided into five main groups, each with a common name and a scientific name. These groups are (1) gastropods << GAS truh pahdz >>, also known by the scientific name Gastropoda << gah STROP uh duh >>, (2) bivalves or Bivalvia << by VAL vee uh >>, (3) tooth shells or Scaphopoda << skah FOP uh duh >>, (4) octopuses and squids, or Cephalopoda << sehf uh LOP uh duh >>, and (5) chitons << KY tuhnz >> or Polyplacophora << pah lee pluh KAHF uh ruh >>. A sixth group of mollusk shells, the Monoplacophora << mahn oh pluh KAHF uh ruh >>, is rarely seen. Scientists have found these shells only as fossils or in the deepest ocean waters.

Gastropods

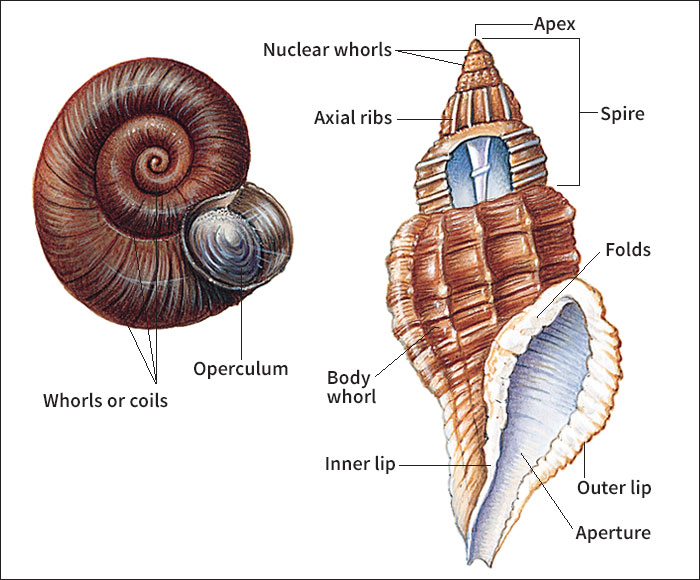

have a single shell made up of one plate or valve. These mollusks are sometimes called univalves, which means one shell. Snails are an important group of gastropods. A majority of snails have a tubelike shell that winds around itself as it grows. The soft body of the snail is in the spiraling tube. Most snail shells grow by winding to the right in a clockwise direction when viewed from above, and are called right-handed shells. A few species of snails possess left-handed shells.

The shells of gastropods have an opening at one end. Most of them have a hard lidlike part called an operculum at the opening. The animal can pull the operculum over the entrance of the shell to keep out small predators, such as fish and crabs.

Gastropods are found in almost every part of the world except on the highest mountain peaks. Some live in the ocean, some in fresh water, and some on land. Many ocean snails have smooth, glossy shells. Others possess shells with deep ridges, rough surfaces, and long, sharp spines. The carrier shell snail attaches bits of shells, stones, and other objects to its shell as it grows. The newly deposited shell substance acts as cement, and when the shell hardens, the objects are held firmly in place. Most snails that live in fresh water or on land have thin, smooth shells. Many tree snails, particularly those of the tropics, have brightly colored shells.

Limpets are also gastropods. Their shells grow almost flat and form a point in the center. The shells of keyhole limpets have a hole at the top, and look like miniature volcanoes.

There are more than 80,000 species of snails. The largest species are the horse conch of Florida and the baler of Australia. Both of these species grow about 2 feet (61 centimeters) long. A giant African snail has a larger shell than any other land snail. It is about 8 inches (20 centimeters) long. Many gastropods have shells so small they can hardly be seen with the unaided eye. A row of 30 Barleeia snail shells is less than 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long.

Bivalves

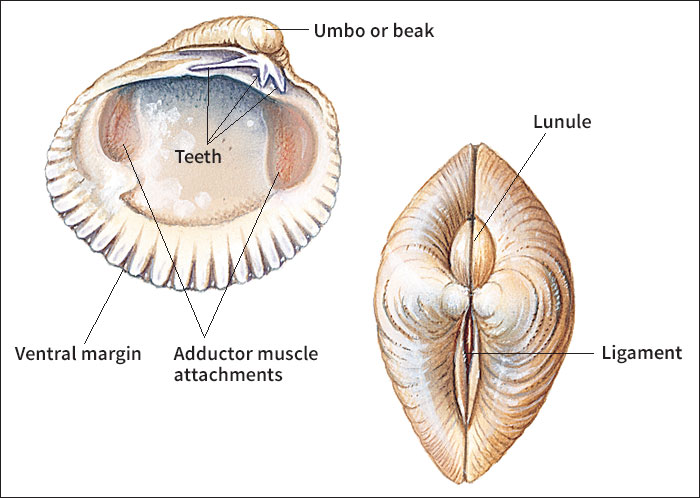

have two matching valves. The valves move on hinges that look like small teeth. Clams, oysters, and scallops are bivalves. Bivalves keep their shells open while they are eating or breathing and when they are undisturbed. A broad band of elastic tissue acts like a prop to hold the valves apart. Bivalves also have one or two strong adductor muscles attached to both valves. If a predator comes near, these muscles snap the shell shut and keep it closed. If the muscles get tired and relax, the shell opens again. A predator usually does not wait this long.

Bivalves are found almost everywhere except on dry land. There are about 11,000 kinds of bivalves. Most of them live in shallow ocean waters near land and in lakes, but a few species live in beds in large rivers. Among the best known of these are the freshwater clams of the Mississippi River Valley. Occasionally, a pearl is found in these shells. But most pearls valued as gems come from ocean-dwelling pearl oysters.

The giant clam of the South Pacific, whose shell can grow 4 feet (1.2 meters) long, is the largest bivalve. The smallest include turton clams of the North Atlantic. They grow about half as large as a grain of rice.

Tooth shells

look like long needles or like miniature elephant tusks. They are sometimes called tusk shells. The shells are hollow tubes that curve slightly and become smaller at one end. Both ends are open.

Tooth shells are found in the sand or mud of the ocean bottom in many parts of the world. Some kinds live close to shore. Others burrow in the ocean floor far below the surface of the water. The small end of the shell sticks up into the water.

Scientists recognize about 500 kinds of tooth shells. The shells vary from 1/2 to 5 inches (1.3 to 13 centimeters). Most are white, but some have green, red, or yellow tints. The most colorful kind is an elephant’s tusk from the Philippines. It is dark green with bluish ribs.

Octopuses and squids.

In this group of marine animals, the cuttlefish and squids have shells inside their bodies. The cuttlefish, also called the Sepia squid, has a chalky cuttlebone inside its body. This shell is light and spongy, but it serves as a strong support for the animal’s body. The Spirula squid has a shell about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long under the skin at the rear of its body. The coiled Spirula shell looks somewhat like a ram’s horn. In tropical countries, waves often wash these coiled shells ashore. Octopuses have no shells.

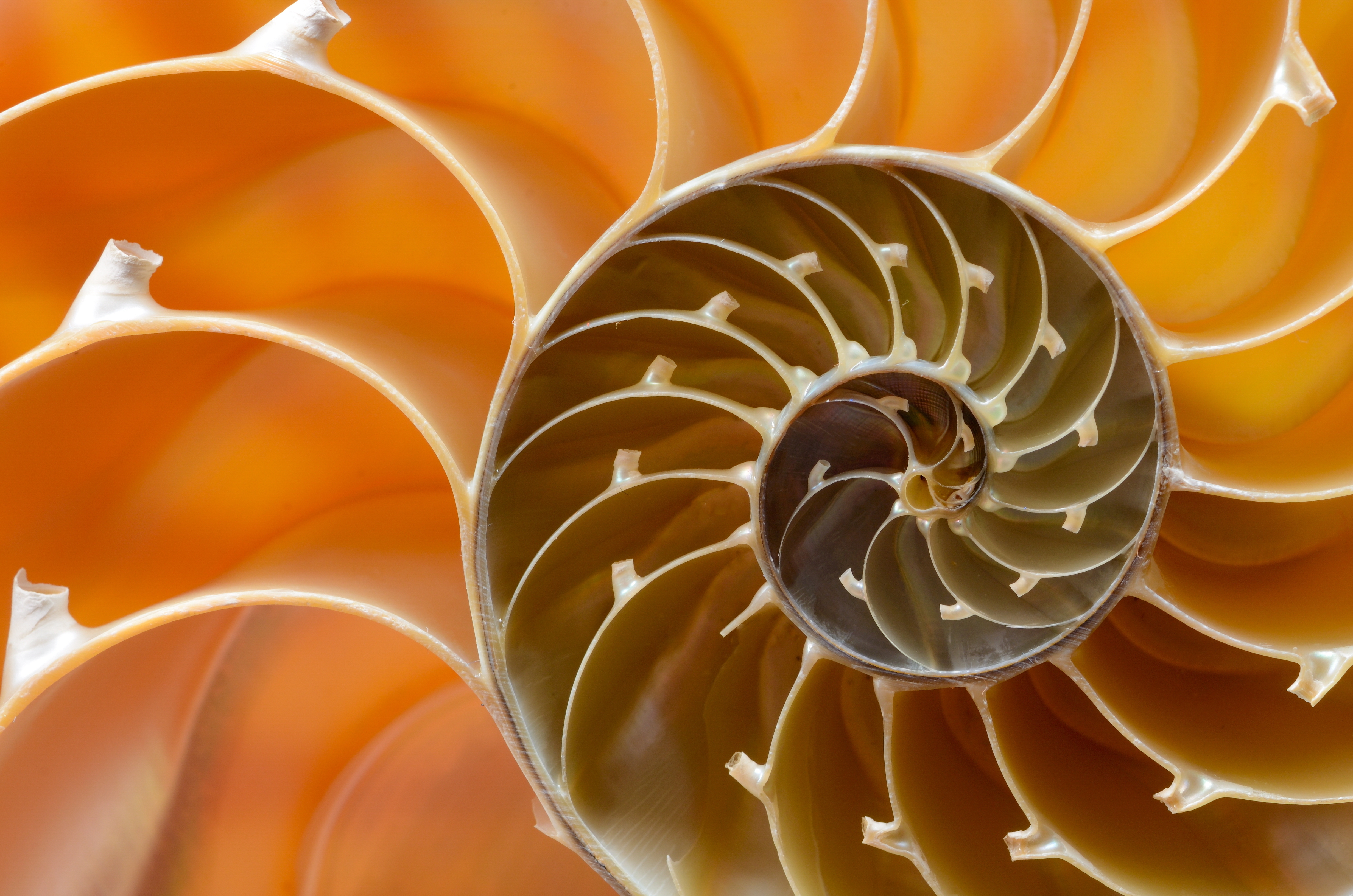

Perhaps the best-known shell of this group is the chambered nautilus, or pearly nautilus. It consists of a series of chambers, each larger than the one before. Its soft body is found in the outermost chamber. Thin walls seal off the other chambers. However, they are connected by a narrow tube that enables nitrogen and other gases to enter and leave the chambers. The coiled shell is cream colored with brown stripes, and the chambers are lined with shiny mother-of-pearl. Nautilus shells grow up to 10 inches (25 centimeters) in diameter. They live mostly in the western Pacific.

The paper nautilus or argonaut has a single, paper-thin shell much like that of the chambered nautilus, but with no chambers. Only the female paper nautilus builds a shell. The female resides in the shell and stores her eggs there. The paper nautilus lives at the surface of warm tropical seas.

Chitons.

A chiton shell consists of eight separate, movable pieces called plates that are held together by a surrounding leathery girdle (belt). The girdle acts like a series of hinges between the plates and enables the animal to bend and move about easily. The individual plates are usually hard, white, and shaped like a butterfly. Chiton shells are also called coat-of-mail shells because they look like tiny suits of armor. Chitons attach themselves to rocks in the sea. Some are less than 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long. The largest chiton, Steller’s chiton of the California coast, grows up to about 1 foot (30 centimeters) long.

Collecting shells

Many people find shell collecting a fascinating hobby. They spend leisure time hunting and cleaning shells, and mounting them in attractive displays. Some collectors become so interested in their hobby that they begin the scientific study of shells, which is called conchology. Hundreds of amateur and professional shell collectors exchange ideas, information, and shells through shell clubs in cities in almost every country.

Beginning collectors gather all the shells they can find, even broken and discolored ones. Serious collectors replace poor shells with those of the finest quality as soon as they can. The best quality shells are obtained from live mollusks—those taken with the animal still inside. These shells have their natural color and luster because they have not been bleached by the sun or worn down by sand or waves. However, people should be careful when they collect the living animals. Some cone snails of the Indian and southwest Pacific oceans can deliver a deadly sting. The next best quality are recently dead shells. Storm waves or outgoing tides leave them on the beach. The poorest shells are dead shells. Most shells found on beaches are dead shells. The sun has faded the colors, and sand and water have dulled the luster.

Searching for shells.

You can find the best sea shells during the night or in the early morning hours at low tide. Use a strong flashlight or lantern to light your way. Wear a bathing suit and soft canvas shoes, and take a small bag or bucket to hold the shells. Look for clams buried in the sand, for snails sheltered under rocks, and for scallops hiding in eelgrass. However, you should put rocks, algae, and logs back in their original position once you are finished. Hunt for sea shells with a companion who can help in case of an accident.

Many kinds of freshwater mussels and snail shells are found in rivers, streams, lakes, ditches, and ponds. Use a dip net to sweep along the grassy edges of ponds. To find the shells of land snails, roll logs over, scrape away the leaves and soil, and look in the cracks of the bark.

As you gather shells, write down the date and the exact location where you find them. Keep these notes with the shells until you add them to your collection. Then put the information on labels that identify the shells.

Cleaning shells.

The best and simplest way to clean live mollusk shells is to boil them. Put the shells in a pan of water, bring the water slowly to a boil, and boil for 5 to 10 minutes. Then let the water cool slowly. With luck, the soft tissue will fall out. Use a twisted safety pin to pull out any remaining soft tissue. Save the snail’s operculum because it belongs with the shell. Wash the shells with soap and water, and place them on paper to dry in the sun. Very small live shells can be soaked in alcohol for several days, and then dried in the sun.

Displaying shells.

You can mount your shells on cardboard, or you can put them on cotton in flat boxes with glass or plastic covers. Some collectors use a cabinet with large drawers to store their shells. A square cardboard tray holds each kind of shell. A label bears the name of the shell and tells where, when, and by whom it was collected. The label should describe the shell’s surroundings, such as grass, mud, sand, or depth of water. A logbook serves as an index to the shells in the collection and gives further information about them.

Every part of a shell helps identify it. For example, the number and location of the teeth in a shell hinge show that the mollusk belongs to a certain family of clams. The color, ridges, and shape of a snail shell identify the group to which it belongs. Each part of a shell has a special name, such as lip, ribs, or shoulders. The drawings in this article show the parts of shells and name them.

A shell collection should be arranged so that it begins with the shells of the simplest kinds of mollusks. Many shells have popular names, such as mouse cone or Florida cone. These names can vary from one country to another, and even from one area to another. For this reason, collectors identify shells by their scientific names. These names are in Latin and are understood by collectors and biologists in all parts of the world. The Latin name of the mouse cone is Conus mus, and that of the Florida cone is Conus floridanus.

Conserving shells.

Scientists believe that over-collecting of shells and pollution have caused some mollusks to become scarce. To help conserve mollusks, do not collect more shells than you need. One or two good specimens of a species should be enough for your collection. Avoid collecting freshwater mussels, many of which have become endangered. People who illegally collect endangered species face a stiff fine.

Uses of shells

In prehistoric times, cowrie and tooth shells were used as money. The Phoenicians and Romans made a purple dye from murex sea snails. They believed that cloth colored with this dye was more valuable than gold. Indigenous (native) peoples of North and South America also used shells as money. In North America, people carved wampum beads from large clam shells and parts of the knobbed whelk of the Atlantic Coast.

The color and luster of shells have made them especially useful as decorations and for jewelry. Before plastic became popular, manufacturers commonly cut the shells of freshwater mussels to make buttons. Today, craftworkers use mother-of-pearl from abalone and oyster shells to decorate fancy boxes, jewelry, and musical instruments. Artists carve raised designs called cameos in many kinds of shells to make jewelry. Conchs and some other large shells can be polished and used as lamp bases or paperweights. Craftworkers fasten many kinds of small shells together in the shape of animals or dolls, or to form attractive designs.

In the Philippines, the thin, almost transparent shells of the placuna oyster serve as window “glass.” The shells are cut into small squares and put into narrow wooden frames. The frames are then fastened together to make a large window.

Scientists sometimes use shells to help them in their work. Shells drilled from the ocean floor provide clues to water temperatures in ancient times. Oil prospectors search for certain fossil shells in deserts and prairies. The shells show that the area was an ocean bed in ancient times. Large oil pools formed in many of these beds.

People also use shells in their diet. Oyster shells provide a good natural source of calcium. People can take tablets containing ground up oyster shells as a calcium supplement.