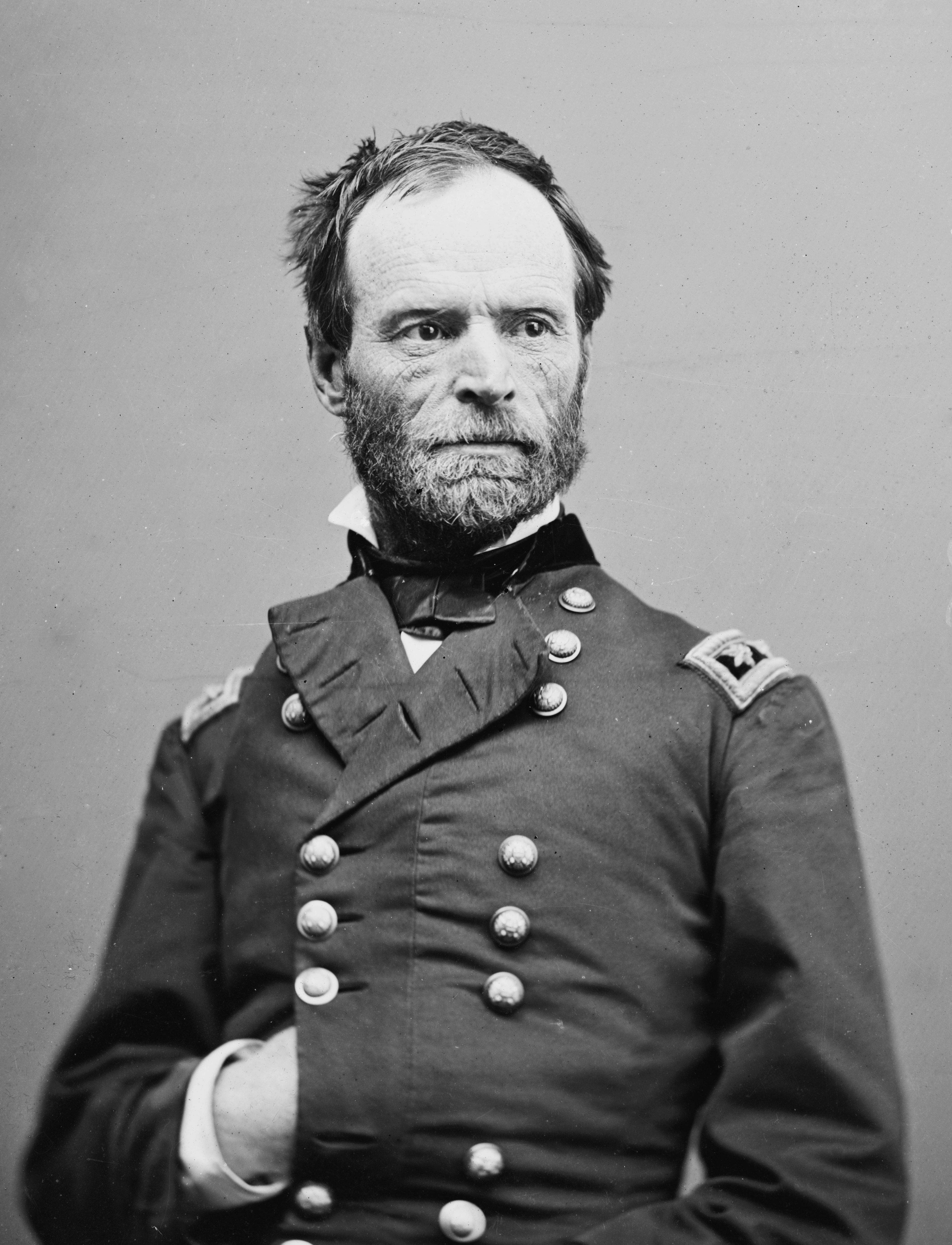

Sherman’s March was a controversial military campaign at the end of the American Civil War (1861-1865). From November 1864 through April 1865, Union General William T. Sherman marched 62,000 troops through Georgia and the Carolinas. On this march, Sherman’s troops destroyed much of the South’s military and economic resources. Some people believe that Sherman and his men terrorized civilians, while others believe that Sherman’s March helped bring about the end of the war.

Background.

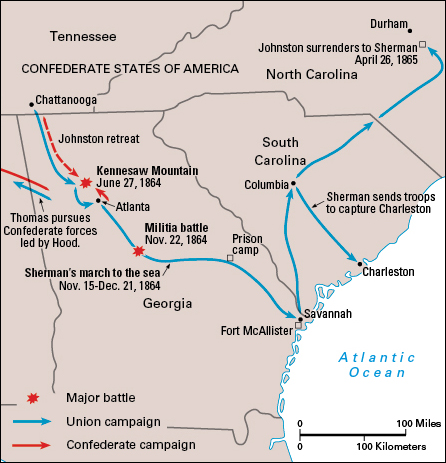

In May 1864, Sherman’s army of about 100,000 men advanced from Chattanooga, Tennessee, toward Atlanta , Georgia, about 115 miles (185 kilometers) south of Chattanooga. Confederate General Joseph Johnston opposed him with about 60,000 troops. Sherman forced Johnston south to the outskirts of Atlanta. On July 17, Confederate President Jefferson Davis replaced Johnston with General John Bell Hood . Hood made several failed attacks that depleted his army, and on September 1, he evacuated Atlanta. Union troops occupied the city the next day.

In an attempt to draw Sherman out of Atlanta, Hood’s army attacked Sherman’s railroad communications with Chattanooga. But Sherman chose not to chase Hood along the railroad and instead planned to march across Georgia about 285 miles (460 kilometers) to Savannah. Sherman felt that if he could destroy the South’s military and economic resources, the Confederates would no longer have the ability, or even the will, to fight.

General Ulysses S. Grant , who commanded all Union armies, and President Abraham Lincoln initially opposed Sherman’s plan. They did not want Sherman to abandon his supply line and leave Hood and the Confederates behind. Sherman altered his plan to appease his superiors. He planned to send some of his troops along with General George H. Thomas to fight Hood’s army, while Sherman marched the remainder to Savannah. Including troops already stationed in Tennessee, Thomas would have about 60,000 men to fight Hood’s 35,000. Sherman eventually persuaded Grant to back his plan. Grant, in turn, persuaded Lincoln.

March to the sea.

On November 15, Sherman left Atlanta and headed for Savannah with 62,000 troops. The Union army burned much of Atlanta before leaving. Not many Confederate troops were stationed between Atlanta and Savannah, so Sherman spread out his troops by dividing his army into two wings that marched on a 50-mile (80-kilometer) front across Georgia. During the march, Sherman had no communication with the North. Not even Lincoln or Grant knew where he was.

Since Sherman was separated from his supply lines, he ordered the army to “forage liberally on the country during the march.” Each morning, foraging soldiers called “bummers” were sent ahead to find food and supplies for the army. Sherman also ordered the soldiers not to “enter dwellings or commit any trespass” and to “leave with each family a reasonable portion for their maintenance.” Straggling soldiers, enslaved people who had been freed, and others who were not part of Sherman’s army stole from homes and burned buildings. Confederate soldiers were known to execute bummers who were caught foraging.

Sherman’s men also destroyed railroad tracks. To ensure that the tracks could not be used again, the soldiers created “Sherman’s neckties” by heating the tracks and wrapping them around trees and poles. The Confederates, meanwhile, attempted to slow Sherman’s army by planting torpedoes (land mines) in its path. However, they stopped this practice after Sherman ordered captured Confederate prisoners to walk ahead of his army and locate the mines. Sherman’s soldiers became increasingly angry toward the Confederates after they encountered emaciated (starved to extreme thinness) Union prisoners who had apparently been mistreated at the Millen, Georgia, prison camp.

Sherman’s men fought one battle on their way to Savannah. On November 22, they defeated a Georgia militia that had attacked them near Macon, Georgia. The Georgia militia—which included boys under 16 and men over 60—suffered about 600 casualties in the battle, while Sherman lost only about 60 men.

During the march, about 25,000 freed enslaved people followed Sherman’s army. Sherman, who did not want the burden of feeding additional people, tried to stop them from following. Many of them obeyed, but others continued to travel behind the group. On December 9, one of Sherman’s officers sought to prevent the formerly enslaved people from following the army across Ebenezer Creek, about 20 miles (32 kilometers) from Savannah. The officer ordered the removal of a pontoon (floating) bridge and left the followers on the other side. However, because the people were being pursued by Confederate cavalry, many of them drowned while trying to swim to safety.

On December 13, Sherman captured Fort McAllister, a Confederate fortification south of Savannah. The capture enabled the Union Navy to supply Sherman’s army with food and other provisions. It also allowed Sherman to regain communication with the North. On December 21, Sherman occupied Savannah and sent a message to President Lincoln: “I beg to present to you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

March through the Carolinas.

On Feb. 1, 1865, Sherman left Savannah and headed north into South Carolina. South Carolina had been the first state to secede (withdraw) from the Union and was considered the breeding ground of the Southern independence movement. As a result, Sherman’s army was motivated by revenge. The troops burned and looted on a scale much worse than in Georgia.

Many Southern military leaders felt that it would be impossible for Sherman’s army to march through the swamps of South Carolina during the winter. However, Sherman’s men built roads and bridges and marched through the swamps. Confederate General Johnston stated: “When I learned that Sherman’s army was marching … at the rate of a dozen miles a day, I made up my mind that there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar.”

On February 17, Sherman captured Columbia, the capital of South Carolina. That night, most of the city was burned. The Confederates blamed Sherman for the fire, but Sherman denied that his troops had set it. Union soldiers, including Sherman himself, helped put out the fires. When the city of Charleston, South Carolina, surrendered, it was spared. Sherman and his troops moved on into North Carolina, but they did not cause as much destruction there as they had in South Carolina.

On February 22, Confederate President Jefferson Davis appointed General Johnston to command the remaining Confederate forces in the Carolinas. Johnston gathered about 20,000 men and confronted Sherman in mid-March, but his army was defeated by Union troops at Averasborough, North Carolina. From March 19 to March 21, the two sides fought again at Bentonville, North Carolina. There, the Confederates had initial success against a wing of Sherman’s army, but Union reinforcements stopped the Confederate attack. On the night of March 21, Johnston withdrew his army. Sherman’s army chased Johnston’s army for a few miles before heading to Goldsboro, where Sherman’s men were joined by more Union troops.

Aftermath.

On April 9, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. After hearing of Lee’s surrender, Johnston proposed a cease-fire to Sherman. On April 18, Johnston surrendered to Sherman near Durham, North Carolina. However, President Andrew Johnson —who had recently taken over the presidency after Lincoln’s assassination —thought the terms granted by Sherman were too generous. President Johnson rejected the terms and instructed Sherman to renegotiate with Johnston. On April 26, Johnston formally surrendered his army to Sherman under terms similar to those Grant had given Lee. About a month later, the last Confederate army in the field surrendered, and the Civil War was over.