Smell is one of the most important and basic senses in animals and human beings. Some animals use the sense of smell to recognize their home territory, animals of their own kind, and other kinds of animals. They also use smell to find food and mates. The scientific term for smell is olfaction, and the system by which we smell is known as the olfactory system.

How odors are detected.

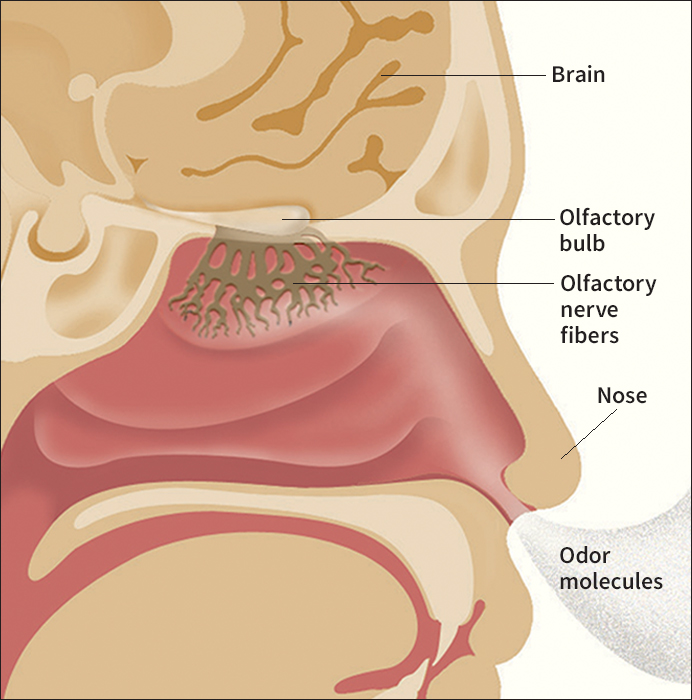

People and land-dwelling vertebrates (animals with backbones) detect smells by breathing or sniffing air that carries odors. Odors come from molecules of gas that have been released into the air from many different substances. These molecules stimulate receptor cells deep inside the nose. The cells, which are part of the olfactory nerves, are on layers of mucus-covered tissue. This tissue covers nasal bones called turbinates or conchae. The receptor cells send the impulses created by the odor along the olfactory nerves.

The olfactory nerves then carry the impulses to a part of the brain called the olfactory bulb. In dogs and some other vertebrates, the olfactory bulb is large, but in people it is relatively small. The size of an animal’s olfactory bulb may be an indication of how important the sense of smell is to that animal. The type of odor smelled determines where the nerve impulses arrive in the olfactory bulb. From the olfactory bulb, the nerve impulses travel toward the forebrain, at the front of the cerebrum of the brain. Parts of the forebrain process the impulses into information about the odor.

Scientists estimate that humans can distinguish as many as 1 trillion different odors. However, they do not know exactly how different smells are distinguished. One explanation is that molecules of certain odors become more quickly and more strongly attached to the mucus at a particular place on the turbinates than do other molecules. Therefore, molecules of certain kinds of odors will always stimulate the same receptor cells on the conchae. According to this theory, an odor is distinguished by how fast and where its molecules become attached to the receptor cells.

Another theory is that odor molecules stimulate any one or combination of receptor cells differently. Each receptor cell’s genes may cause the production of special proteins that attach easily only to certain odor molecules. The attachment of a few odor molecules triggers nerve impulses from the receptor cell to the brain.

Taste and smell.

Generally, we taste and smell food at about the same time. Thus, we have come to think of the two senses as being related. But they are, in fact, separate. Only at some point in the brain are the separate senses combined.

The smell-stimulus parts in food can be separated from the taste-stimulus parts. This separation can be achieved by blowing clean air into the nose while the food is put into the mouth, or by allowing food to contact the taste buds but not the air. When smell stimuli are separated from taste stimuli, people cannot identify some foods and beverages—for example, cherries, chocolate, and coffee—though they still taste them.