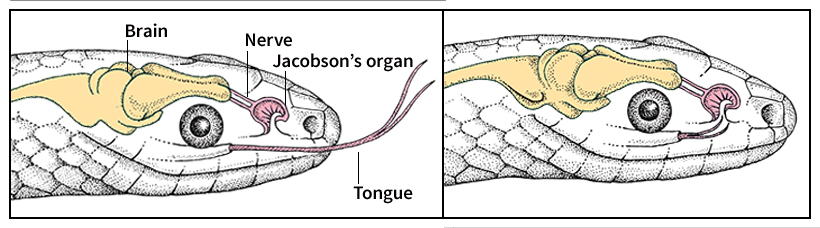

Snake is an animal with a long, legless body covered in dry scales. To move about on land, a snake usually slides on its belly. Clear scales—instead of movable eyelids—cover the eyes of a snake. As a result, the eyes are never truly closed. Snakes have a narrow, forked tongue, which they repeatedly flick in and out. The tongue carries odors to a special sense organ inside their mouth.

Snakes are closely related to lizards. Together, snakes and lizards belong to a class of animals called reptiles. Like other reptiles, snakes are cold-blooded, or ectothermic. The body of a cold-blooded animal stays about the same temperature as its surroundings. Snakes regulate their body temperature through their behavior. For example, they raise their body temperature by lying in the sun. They lower it by crawling into the shade or into cool water. In contrast, mammals and birds are warm-blooded, or endothermic. The body of a warm-blooded animal stays around the same temperature regardless of its surroundings.

Snakes live on every continent except Antarctica. They inhabit deserts, forests, oceans, streams, and lakes. Many snakes live on the ground. Some make their homes underground. Others live in trees. Still others spend most of their time in water. Only a few areas in the world have no snakes. Snakes cannot survive where the ground stays frozen the year around. Thus, no snakes live in the polar regions or at extremely high elevations in mountains. In addition, some islands, including Ireland and New Zealand, have no native snakes.

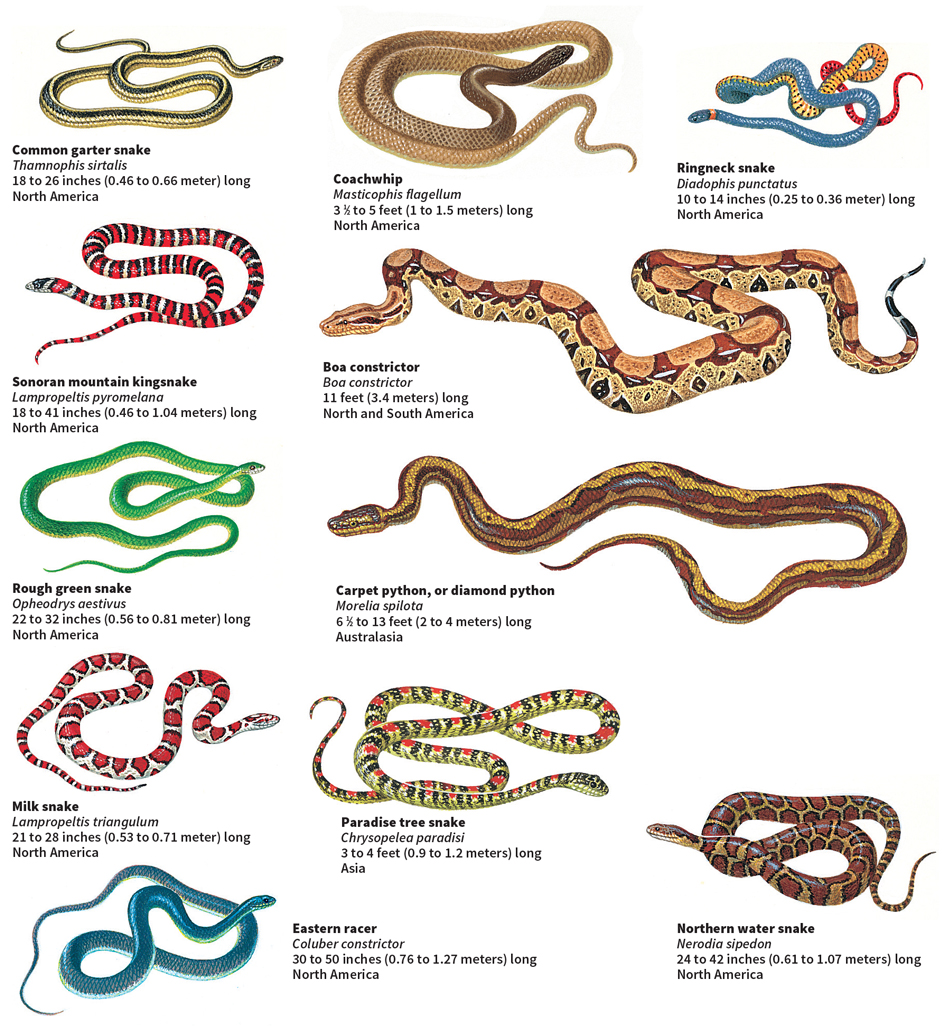

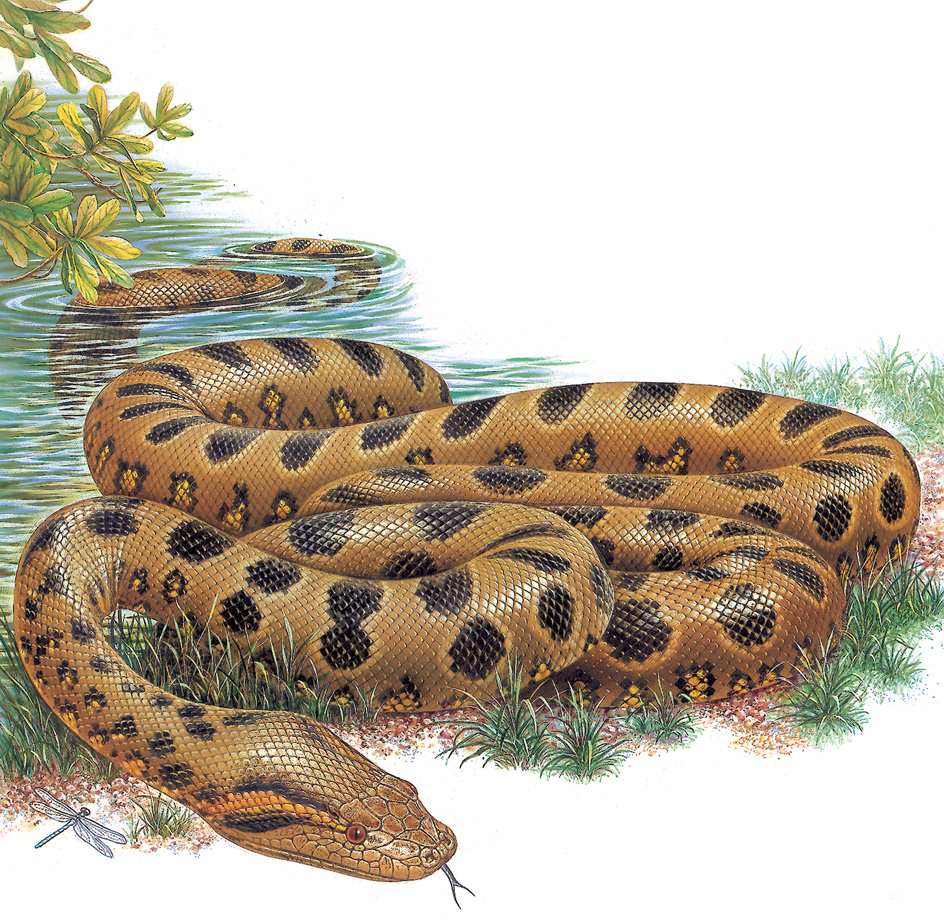

There are thousands of species (kinds) of snakes. The greatest variety live in the tropics. The largest snakes are the green anaconda of South America, the reticulated python of Southeast Asia, and the African rock python. All three can reach nearly 30 feet (9 meters) long. Among the smallest snakes is the Barbados thread snake. This Caribbean snake grows only 4 inches (10 centimeters) long. When coiled, it can fit onto a small coin.

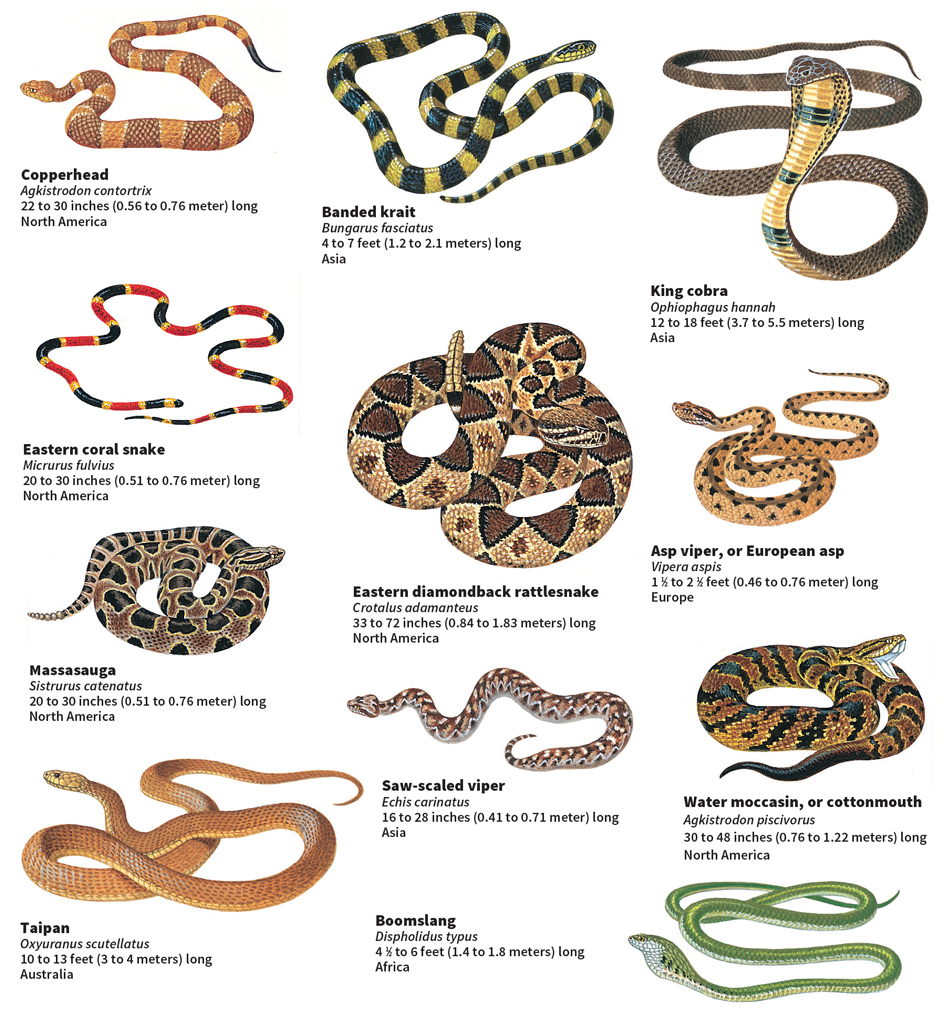

Some snakes can inject venom (poison) through their fangs when they bite. About 15 percent of all snake species have venom that is harmful or fatal to human beings. About 25 species cause most of the deaths from snakebites. These include the Indian cobra of Asia, the black mamba and the saw-scaled viper of Africa, and the tiger snake of Australia.

Some people fear and dislike snakes, partly because some species are venomous. But snakes are mostly harmless to people. Many myths and superstitions may have inspired people to fear snakes. But snakes are an important part of the balance of nature. Snakes also help control the numbers of rats and other pests.

The bodies of snakes

Body shape.

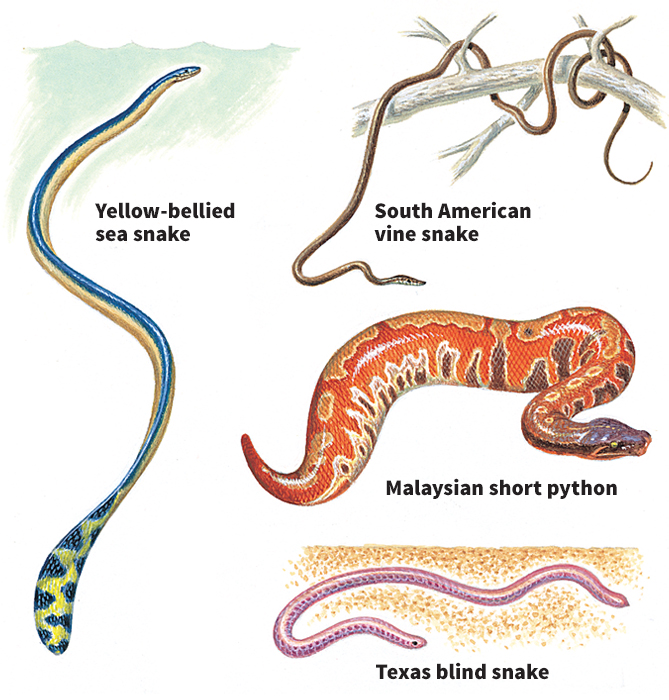

Snakes vary in body shape. Some snakes, such as the Gaboon viper of Africa, have a thick, stout body. Certain tree snakes have a thin, long, lightweight body. Such a snake might resemble a vine or a branch. Sea snakes have a body that makes them good swimmers. Their body is flattened vertically, and their tail resembles a paddle. In most species of snakes, the males and females look alike.

Scales and color.

Dry scales cover the body of a snake. The scales may be smooth or ridged. Most snakes have overlapping scales that stretch apart. The belly scales, called ventral scutes, consist of one row of enlarged scales extending from the neck to the tail among most species. The belly scales may help the snake move. The side and back scales vary in size and shape among different species.

The scaly skin of a snake has two layers. The inner layer consists of cells that grow and divide. The cells die as they are pushed upward by new cells. The dead cells form the outer layer of skin. From time to time, a snake sheds the outer layer of skin because it is worn or because the snake has grown.

The skin-shedding process is called molting or ecdysis. For a short time before molting, a snake is less active than usual. The animal’s scales, including its eye scales, become clouded. About one day before molting, the snake’s skin appears bright, as if the snake had already molted. However, a short time later the snake begins to loosen its dead skin. It starts around the mouth and head by rubbing its nose, catching the skin on a rough surface. The snake then crawls out of the old skin, turning it inside out in the process.

How often a snake molts depends on its age, growth, activity, and health. Young snakes shed more often than older ones. Snakes in warm climates are active for longer periods than those in cooler climates. As a result, they molt more often. Some pythons of the tropics shed six or more times a year. In contrast, some North American rattlesnakes average two or three molts a year. They may add a new section to their tail rattle each time they molt. Snakes with skin injuries also molt more often.

A snake’s color pattern comes chiefly from special pigment cells deep in the skin. Snakes have many different colors, including black, blue, brown, green, orange, red, and yellow. But some blue or purple coloration may be due to the way light is reflected from the surface of the scales. The color seems to change as the snake moves, an effect called iridescence.

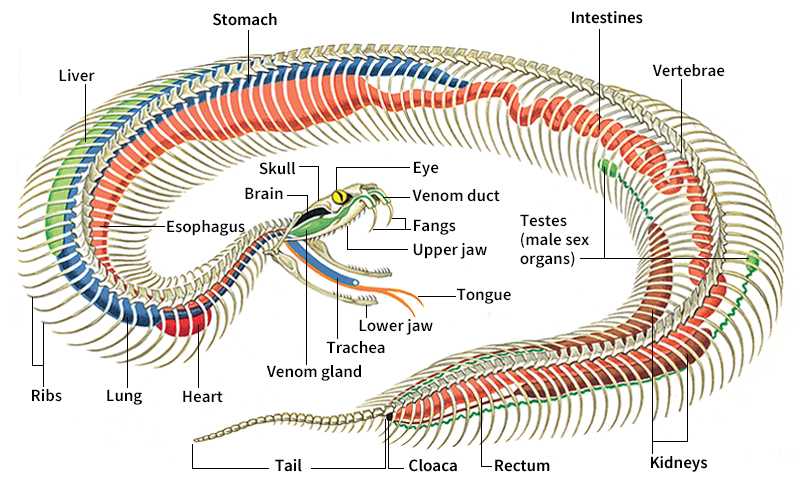

Skeleton.

The main parts of a snake’s skeleton are the skull, vertebrae, and ribs. A few snakes, such as blind snakes, boas, and pythons, have vestiges of hind legs or hipbones. A vestige is a remaining trace of a body part that a group of animals has lost through evolution (change over time). Snakes that have such vestiges show their close relationship to lizards.

Skull.

Most of the bones of a snake’s skull are loosely connected. Bone completely encases the brain, however. In most snakes, the lower jaw has two bones connected at the chin by an elastic tissue, or ligament. This structure enables the bones to stretch wide apart. The lower jaw is loosely attached to the upper jaw. Several bones of the upper jaw and roof of the mouth also are loosely joined to one another and to the rest of the skull. The two sides of the jaws can move separately.

The flexible structure of the jaws enables most snakes to open their mouth wide enough to swallow animals that are larger than their own head. To swallow an animal, a snake moves first one side of its jaws forward and then the other side. Some bones of the lower and upper jaws have pointed teeth that curve back toward the throat. These teeth are not for chewing. Instead, they stick into prey and prevent it from escaping as it is swallowed whole. As the snake alternately draws each side of its jaws forward, it pulls the animal toward the throat. Saliva in the snake’s mouth and throat eases the passage of the prey. The snake’s saliva may also begin digesting the prey before it reaches the stomach.

In some cases, a snake may take more than an hour to swallow an animal. A special feature prevents the trachea (windpipe) from being blocked while the snake’s mouth and throat are full. The trachea moves forward over the tongue so that the snake can breathe while swallowing.

Vertebrae.

The backbone of snakes consists of an unusually large number of vertebrae. Snakes have from about 150 to more than 430 vertebrae, depending on the species. Strong, flexible joints connect the vertebrae. These joints enable the body to make a wide range of movements, including coiling into a ball.

Ribs.

A pair of ribs is attached to the sides of each vertebra in front of the tail. The rib tips are not joined together along the belly and so can be extended outward. After a snake has swallowed a bulky meal, the ribs spread out as the stomach expands.

Muscles.

As many as 24 small muscles are attached to each vertebra and rib in a snake’s body. These muscles connect one vertebra to another and the vertebrae to the ribs. Snakes use most of these muscles to move.

Internal organs.

The lung, liver, and other major internal organs of snakes are long and slender. Most snakes have only one lung, though some have a vestige of a second lung. Snakes have a pair of kidneys and a pair of sex organs—ovaries in a female and testes in a male. The paired organs lie one on each side of the body. But each pair is staggered from front to back. In most animals, paired organs lie across from each other.

In most snakes, the stomach and intestines are specially suited for handling bulky food. Both have a thick lining that can expand greatly. The stomach and intestines produce substances called enzymes. The enzymes break down food into smaller particles that can be absorbed. Snakes can digest the entire body of their prey, except for hair or feathers. Bone may be completely digested within 72 hours. Waste products pass out of a snake’s body through an opening called the cloaca or vent. The vent marks the end of the snake’s trunk and the beginning of its tail. In female snakes, the cloaca is also the cavity into which the oviducts (tubes from the ovaries) empty.

Snakes that eat large meals use a great deal of energy digesting food. Between meals, their intestines, liver, and other internal organs may shrink. The snakes’ bodies must restore these organs to their full size before they can digest new food.

Sense organs.

Snakes can hear sounds and feel vibrations. Some snakes have excellent eyesight. Most can see movement. But snakes rely mainly on special sense organs to provide information about their surroundings.

Snakes have an eye on each side of the head, which gives them a wide field of view. A clear scale called a brille covers each eye. The snake sheds these scales and replaces them each time it molts.

Snakes lack outer ear openings. However, they have inner ears and can hear a limited range of sounds carried in the air or through the ground. Certain bones in a snake’s head transmit sound waves to the inner ear.

An organ of smell called the Jacobson’s organ enables snakes to detect odors. The Jacobson’s organ consists of two hollow sacs in the roof of a snake’s mouth. The sacs have many nerve endings that are sensitive to odors. A snake sticks out its tongue to pick up scent particles in the air or on the ground. When the snake pulls its tongue back into the mouth, these particles enter the Jacobson’s organ. The organ enables a snake to recognize and follow the scent trail of its prey. In addition, a snake can recognize a member of its own species and detect whether the individual is male or female.

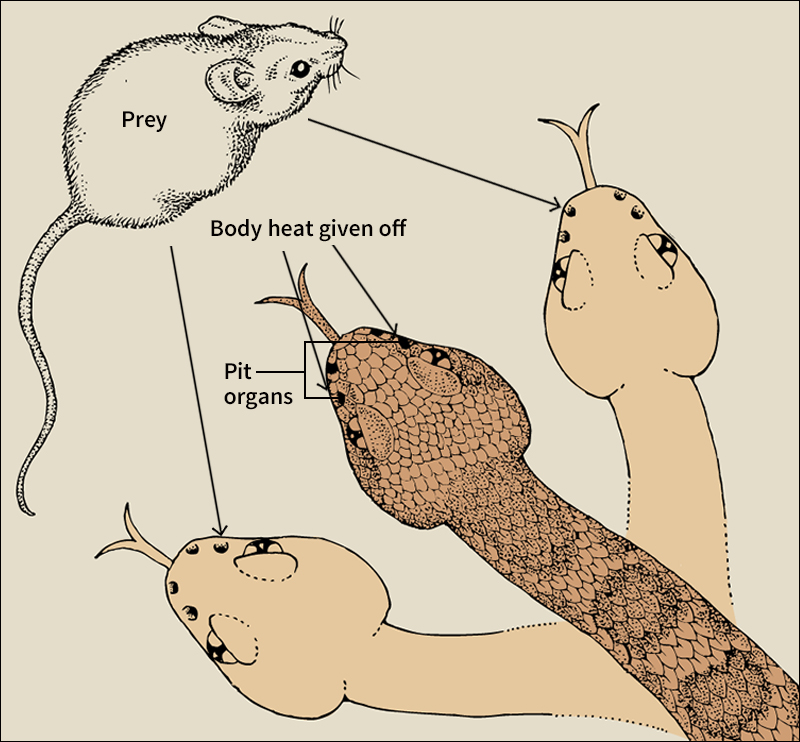

Certain snakes have special heat-sensitive pit organs. Pit vipers have two pit organs, one on each side of the head, between the eye and nostril. Boas and pythons have many pits along the lip of the upper jaw. Pit organs enable a snake to detect the exact location of a warm-blooded animal by its body heat. Thus, the snake can accurately direct its strike at warm-blooded prey even in the dark. A snake with pit organs can sense a change in temperature of less than 1 °F (0.5 °C) near its head.

Fangs and venom glands.

Only venomous snakes have fangs and venom glands. Venom glands developed from salivary glands (glands that produce saliva). Venomous snakes bite a victim with their fangs and inject venom into the wound. Several kinds of snakes can also spit venom.

Most venomous snakes have fangs in the front of the mouth. The two foremost teeth in the upper jaw form hollow fangs, which act somewhat like hypodermic needles. A tube connects each fang to a venom gland on each side of the upper jaw. The snake may shed and replace the fangs several times a year.

There are two main groups of venomous snakes—vipers and elapids. The two groups have different fangs. Vipers, which include cottonmouths and rattlesnakes, have long, movable front fangs. When not in use, the fangs fold back into a sheath on the roof of the mouth. When the snake strikes, the fangs swing forward. Elapids, which include cobras, coral snakes, and sea snakes, have short front fangs that are fixed in place.

A third group of venomous snakes is the colubrids << kahl yuh brihdz >>. Some colubrids have short rear fangs that are fixed. They must chew on their prey to release the venom. Most colubrids are harmless to people, but some have injured or even killed people.

A snake uses its fangs and venom chiefly to slow or kill prey. Venom glands produce a number of enzymes and other substances that can cause death. After a snake bites its prey, some of these enzymes begin the process of digestion even before the snake starts to swallow the animal. However, the snake usually waits for the venom to cause unconsciousness or death before swallowing.

In addition to enzymes, most snake venoms include neurotoxins and hemotoxins. Neurotoxins affect the nervous system. They cause difficulties in breathing, swallowing, and heart function. Hemotoxins damage blood vessels and body tissues. Sea snakes have an unusual type of venom that directly affects muscles.

The life of snakes

Snakes are difficult to observe in their natural surroundings because they stay hidden much of the time. Little is known about the ways of life among many species. Scientists who study snakes and other reptiles and amphibians are called herpetologists. They have detailed information about the behavior of relatively few species of snakes.

In general, the life of a snake consists mainly of moving about alone in search of food, shelter, or a mate. Many snakes are active during the day. Others move about at night. During certain times of the year, a shift in activity can occur. Snakes sometimes become inactive for long periods because of cold or hot weather, or because of scarce water or food.

Some snakes stay within a limited area. For example, a study of prairie rattlesnakes showed that the males roamed an area about 3/4 mile (1.2 kilometers) in diameter. The females kept to an area about 1/6 mile (0.3 kilometer) in diameter.

How snakes move.

Snakes often seem to slither swiftly. But they actually move slowly compared with other animals. Garter snakes and pythons, for example, crawl less than 3 miles (5 kilometers) per hour. The fastest snake may be the African black mamba. It can move at speeds of 7 miles (11 kilometers) per hour over a short distance. In comparison, people can sprint 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 kilometers) per hour.

Snakes have four main ways of moving. They are (1) lateral undulation, (2) rectilinear movement, (3) concertina movement, and (4) sidewinding. Some snakes also move in other, unusual ways.

Lateral undulation

is the most common way in which snakes move. The snake flexes its muscles, first on one side of its body, then on the other. The loops of its body push against the ground. In this manner, the snake’s body moves forward. Snakes also use lateral undulation to propel themselves through water.

Rectilinear movement

is also known as creeping. Snakes often use this method to climb trees or pass through narrow burrows. Many thick-bodied snakes, such as puff adders and pythons, may use rectilinear movement when crawling on the ground.

In rectilinear movement, the snake contracts muscles that pull its belly scales forward. The back edges of the scales catch on a rough surface. The snake then contracts other muscles, which push the scales against the surface. Pushing moves the body forward.

Rat snakes and many other snakes have belly scales especially suited to climbing. The edges of the scales are squared. They readily catch on any rough surface that the snake climbs, such as tree bark.

Concertina movement

is often used by snakes to crawl through trees or advance over smooth surfaces. The front part of the snake’s body moves forward and coils slightly, pressing against the surface to anchor itself. The snake then pulls its back end forward, coils that part, and presses it down. The back end grips the surface, enabling the front part to move forward again.

Sidewinding

is used chiefly by certain snakes that live in areas with loose soil or sand. These snakes include the sidewinder of North America and the carpet viper and horned viper of Africa. In sidewinding, the snake’s head and tail serve as supports. The snake lifts the middle of its body off the ground and moves it sideways. The snake then moves its head and tail into position with the rest of its body. It then repeats the sequence.

Unusual ways of moving.

Many small species of snakes seem to jump when trying to escape from danger. They hurl their body forward or to the side by rapidly straightening from a coiled position. Certain snakes of southern Asia can glide from a high tree limb to a lower one. They leap from a branch and spread their ribs, which flattens the body and helps slow the fall. Scientists have observed these snakes gliding up to about 330 feet (100 meters).

Reproduction.

Snakes ordinarily reproduce sexually. In sexual reproduction, a sperm (male sex cell) unites with an egg (female sex cell), forming a fertilized egg. The fertilized egg develops into a new individual.

Male snakes have a pair of sex organs called hemipenes. These organs lie inside the base of the tail and can be pushed out through the cloaca. During mating, the male curls his tail under the female’s, inserts a hemipenis into her cloaca, and deposits sperm. Among some species, the sperm can live within the female’s body for several months or even longer. Thus, the eggs may become fertilized long after mating occurs. Male and female snakes do not stay together after mating.

In regions with warm summers and cold winters, most snakes mate in the spring or fall. In the tropics, snakes may mate at any time of the year.

Most snakes lay eggs. The females generally lay eggs in shallow holes, rotten logs, tree stumps, or similar places. The number of eggs laid at one time varies among different species. In many species, the female lays 6 to 30 eggs at a time. Large pythons usually lay about 50 eggs, but they can produce up to 100.

Most female snakes leave their eggs after laying them. But among a few species, including Indian pythons and king cobras, the females may coil on top of their eggs and guard them. Some pythons may also incubate their eggs—that is, keep the eggs warm to help the young develop quickly. A female python curls her body around the eggs and contracts her muscles to produce heat if the temperature is cool. In this way, she keeps her eggs as warm as 85 °F (29 °C), which aids in hatching.

The shells of snake eggs are leathery. The eggs expand as the young grow inside. They typically hatch in about 8 to 10 weeks, depending on the temperature. Females of some species carry their eggs within the body several weeks before laying them. As a result, the eggs are well developed by the time they are laid. They hatch within 2 to 6 weeks. When young snakes are ready to hatch, they slash their shells with a special growth on the upper jaw called the egg tooth. The little snakes shed that tooth shortly after tearing through their shells.

About a fifth of all species of snakes bear live young. Pregnancy among most of these species lasts about two or three months. Some species have more than 100 young at a time, but most bear far fewer.

Newly hatched or newborn snakes live entirely on their own. They must find their own food and shelter. They grow rapidly. The young of some species reach maturity—that is, become able to reproduce—in one year. Among other species, the young mature in two to four years. Snakes continue to grow after maturity.

Regulation of body temperature.

The body temperature of snakes varies with changes in the temperature of their surroundings. However, a snake must keep its body temperature within a certain range to survive. Most snakes can be fully active only if their temperature measures between 68 and 95 °F (20 and 35 °C). They cannot move if their temperature drops below about 39 °F (4 °C). On the other hand, most snakes will die if exposed to temperatures above 104 °F (40 °C).

Snakes maintain their body temperature within the necessary range by moving to warmer or cooler places. They typically raise their body temperature by lying in the sun. After sunset, they may stretch out on a warm surface. Snakes that live underground move to warmer areas in the soil. Snakes avoid excess heat by seeking shelter under bushes, logs, or rocks, or in water. Some snakes that live in the tropics spend the hottest part of the year in a state of reduced activity called estivation.

Snakes that live in regions with cold winters hibernate. They spend the winter in caves, burrows, or other frost-free places where the temperature is constant. In most areas of the world, a snake sheltered 3 feet (90 centimeters) below the surface of the ground is protected from freezing. During hibernation, a snake’s body temperature may measure from about 39 to 41 °F (4 to 5 °C).

If suitable sites for hibernation are scarce, hundreds of snakes of different species may spend the winter in the same place. Such a shared shelter is called a hibernaculum. In the fall and spring, the snakes may be seen near the hibernaculum warming themselves in the sun.

Feeding habits.

Most snakes eat birds, fish, frogs, lizards, and such small mammals as rabbits and rats. Some snakes, such as Asian king cobras and North American kingsnakes, eat other snakes. Large constrictors sometimes eat animals that weigh more than 100 pounds (45 kilograms), such as antelopes and hogs.

Numerous snakes have specialized feeding habits. For example, some species eat chiefly snails. The teeth and lower jaw of some snail-eating snakes are specially adapted for pulling the snails out of their shells. Snakes that eat mainly termites have tiny mouths. They suck the insides of a termite’s abdomen from its body, leaving the less digestible parts. Certain snakes that eat eggs have long spines inside the throat. After the snake swallows an egg, these spines pierce the shell. Then the snake’s muscle contractions crush the egg. The contents of the egg pass through the throat, but the spines prevent passage of the shell. The snake spits out the shell.

Snakes capture prey in various ways. They may wait in ambush, stalk an animal, or pursue it. When a snake strikes, it lunges forward with its mouth wide open. A snake usually can strike effectively only at a distance equal to one-half to two-thirds of its body length.

Most snakes swallow their prey while it is unconscious but still alive. However, venomous snakes generally wait for their venom to kill an animal before they devour it. Constrictors, including boas, bull snakes, kingsnakes, pythons, and rat snakes, squeeze prey until it is unconscious before eating it. A constrictor wraps two or more loops of its body around its catch and then contracts its muscles. The snake squeezes the animal tighter with every breath until it falls unconscious. Some people think constrictors kill by crushing their victims. Actually, constrictors kill by suffocating their prey.

After feeding, a snake may lie in the sun. The warmth raises its body temperature, which speeds digestion. A meal may last a snake a long time. Large snakes, such as boas and pythons, may eat a big meal and then go without another for months. Occasionally, some large snakes fast for more than a year.

Snakes can survive a long time without food for several reasons. Unlike warm-blooded animals, snakes need little energy to maintain their body temperature. Snakes also may remain inactive for extended periods. In addition, snakes store a great deal of fat in their body. During long fasts, they live off this fat.

Protection against predators.

Many kinds of predators (hunting animals) feed on snakes. These predators include large birds, such as eagles and herons. Certain mammals, such as mongooses and hogs, prey on snakes. King cobras and kingsnakes are among the snakes that hunt other snakes.

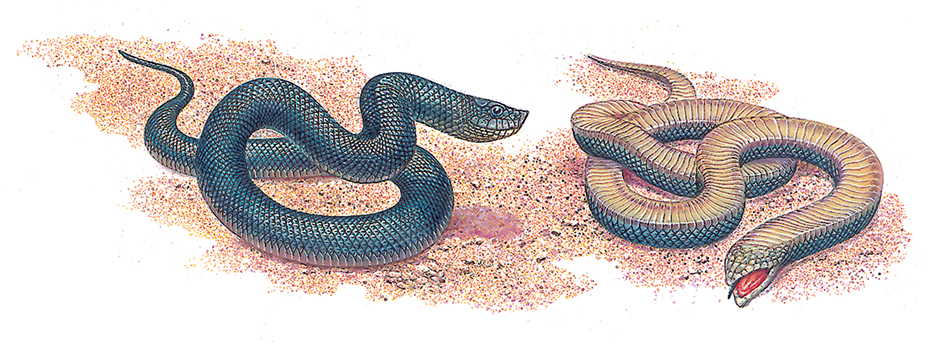

Snakes have a wide variety of defenses against predators. Many species have color patterns that match their surroundings, which helps to conceal them. For example, the North American copperhead has brown bands that blend with the dead leaves on the forest floor, where it lives. The North American smooth green snake has a thin body with a green back. The snake blends in with green vines and other vegetation.

Some snakes have bright colors. For example, the coral snakes of North America have bands of black, red, and yellow. These colors may serve as warning coloration, cautioning potential predators to avoid venomous snakes.

Some harmless snakes may gain protection from their resemblance to venomous snakes. For example, the harmless scarlet kingsnake has a color pattern that resembles that of the venomous coral snake. Predators may avoid the kingsnake, confusing it with the coral snake. This type of protection is called Batesian mimicry.

Snake behaviors also help to defend them against predators. If threatened, a snake may escape by fleeing into a burrow, the water, or some other place where the predator cannot follow. Some shield-tailed snakes of southern Asia can block the entrance to their burrow with their short, blunt tail.

Many snakes make threatening noises when a predator approaches. Some hiss loudly. Most snakes shake their tail when threatened. Rattlesnakes make a distinctive buzzing sound by shaking the rattle, a loose, horny structure on the tail. The African saw-scaled viper makes a rasping sound by rubbing its side scales together.

Some snakes adopt a threatening posture that may frighten away predators. For example, the cobra lifts its neck and spreads its ribs, forming a broad hood. North American hognose snakes and other species may spread their neck ribs and inflate their lung. These actions make them look larger and fiercer. This type of behavior is called a threat display.

Some kinds of harmless snakes mimic the behavior of venomous snakes. For example, kingsnakes and rat snakes vibrate their tail among dry leaves. This action produces a sound like that made by rattlesnakes. Some harmless snakes of Africa mimic the rasping sound of the saw-scaled viper. Certain harmless Asian snakes and the Madagascar leaf-nosed snake spread their ribs and form a hood similar to that of the cobra.

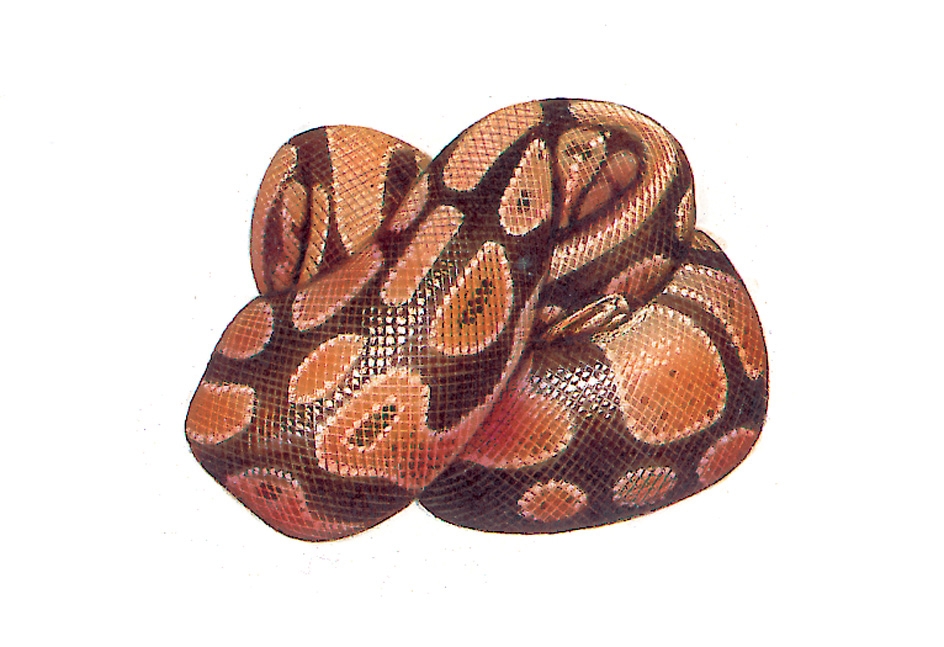

Some animals that prey on snakes have no interest in dead snakes. Thus, certain snakes defend themselves by playing dead. The North American hognose snake is especially well known for this behavior. When threatened, it may twitch violently until it rests upside down with its mouth open and tongue out. After the threat has passed, the snake rights itself and crawls away to safety. The African ball python coils into a tight ball with its head in the middle. This position makes it difficult for predators to reach vulnerable parts of the snake’s body. This defense also is used by North American ground snakes, rubber boas, and other species.

If other defenses fail, a snake may attack. The bite of a venomous snake is a powerful weapon. But the snake could be clawed or bitten before its venom takes effect. The African “spitting” cobra has added protection. It can squirt venom into the eyes of a predator 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 meters) away. The venom produces an immediate burning sensation and can cause blindness. Large constrictors are also a powerful match for most predators. They can quickly coil around an animal and suffocate it, just as they do to their prey.

Battles among male snakes.

Among some snake species, adult males sometimes fight each other. In a typical battle, two snakes rear up and twist their bodies together. They try to push each other downward until one snake retreats. These encounters, called combat rituals, usually occur during the mating season. The victor wins the right to mate with a nearby female. Such battles are especially common among vipers. But they also occur among such small, harmless snakes as North American kingsnakes and European smooth snakes.

Life span.

Scientists do not know how long most snake species live in the wild. Few snakes in zoos survive longer than 15 years.

Snakes and the environment

Snakes and ecosystems.

Snakes are a vital part of many ecosystems. An ecosystem consists of the living and nonliving things in a particular place. Each species of animal in an ecosystem depends on other organisms for food. The feeding relationships among all the animals in an area can help prevent any one species from becoming too numerous. Snakes can help to preserve this balance of nature. See Balance of nature.

In many ecosystems, snakes feed on small animals that grow and reproduce quickly. For example, imagine an ecosystem in which snakes feed on mice. If snakes were removed, the number of mice would grow rapidly. The mice would harm many plants by eating their leaves, stems, and roots. In addition, the mice would soon consume much of the food needed by other animals. Snakes also are fed upon by birds and other animals. These animals might not be able to find enough food without snakes. In this way, removing snakes from an ecosystem would result in much destruction.

Snakes as invasive species.

People have introduced snakes into ecosystems where they do not live naturally. These snakes can become an invasive species—that is, an introduced species that spreads quickly and harms native wildlife.

Snakes have colonized a number of islands. For example, in the late 1940’s or early 1950’s, brown tree snakes came to the island of Guam. The snakes are native to Australia and Papua New Guinea. They may have reached Guam by traveling with military cargo. The brown tree snake is a fierce predator of small animals, including birds and lizards. Animals native to Guam had no experience of tree snakes. Nor were there predators to control the snake’s numbers. The snake soon spread throughout most of the island. It destroyed native bats, birds, and other animals. Most of the island’s native bird species became extinct.

Invasive snake species also threaten native wildlife in North America. Burmese pythons, traditionally considered a subspecies of Indian pythons, have colonized the Florida Everglades. These snakes are large constrictors that are native to Southeast Asia. They can reach about 20 feet (6 meters) long. Researchers estimate that many thousands of Burmese pythons now reproduce in the wild in Florida. They feed on native species, including endangered birds and mammals. They also compete with native snake species. Scientists worry that the pythons may spread to similar areas elsewhere in North America. Boa constrictors also have become established in southern Florida, and scientists think that African pythons probably have as well.

Snake conservation.

Many species of snakes are abundant and face few threats to their survival. But humans have caused a decline in the numbers of many other snake species. Scientists are not certain how many snake species are in decline. That is partly because scientists have not studied wild snakes as much as they have many other animals. Also, snakes can be difficult to survey because they may remain hidden most of the time. However, many scientists consider it likely that at least one in four snake species are threatened.

Species that are in danger of becoming extinct include the broad-headed snake, the Jamaican boa, and the giant garter snake. People have already caused the extinction of several snake species, including the Round Island burrowing boa and the Saint Croix racer.

The single largest threat to snakes is habitat destruction. People destroy the places where snakes live by clearing land for farms, cities, or other uses. Some snakes are threatened because people have captured so many for the pet trade. Snakes also are threatened because people kill them for their skin. For example, Burmese pythons are invasive in Florida, but they have become threatened in their native Asia because so many have been taken for pets and skins. People also kill many snakes needlessly, out of fear or misunderstanding.

Snakes and people

The uses of snakes.

Snakes provide many benefits to human beings. They can aid farmers by preying on pests, such as mice and rats. Because these pests may carry disease, snakes can help to protect human health. In some countries, such as China, people eat the meat of snakes. The skin of many kinds of snakes is used to make such items as belts, boots, and handbags. However, this use of snakeskin has threatened the survival of some species.

Snake venom has several uses in medicine and biological research. Antivenin, which is used to treat snakebite, is prepared from the blood of animals that have been injected with venom. Certain painkilling drugs are prepared from neurotoxins in venom. Researchers use the powerful enzymes in venom to break down complex proteins for biochemical studies.

Snakes as pets.

Some people keep snakes as pets. However, many snake species do not make good pets. Some snakes move around little and stay hidden most of the time. Snakes may have unusual feeding habits, which makes it difficult to give them an adequate diet. Venomous snakes make especially poor pets. In addition, some snakes may be easy to care for when young, but they soon grow huge. Unfortunately, people who feel they can no longer care for the animals sometimes release them into the wild. For example, pet owners likely released the Burmese pythons that colonized the Everglades. Pets should never be released into the wild, and it is illegal in many places.

People who would like to keep a snake as a pet must commit to feeding and caring for the animal. They should carefully consider whether a particular species would make a good pet. Most people cannot properly care for large constrictors, such as Burmese pythons. Because some snake species have become threatened in the wild, it is better to buy a snake that was bred in captivity rather than captured.

Snakebites.

Snakes bite people relatively rarely, and most snakebites cause only minor injuries. The majority of snakes do not have venom. Even venomous snakes often inflict dry bites. A dry bite occurs when a venomous snake pierces the skin with its fangs but does not inject venom. Some researchers think that venomous snakes can control how much venom they inject into a bite wound.

Dangerous snakebites are rare in most of the world. Even in Australia, which has a variety of venomous snakes, few people suffer dangerous bites. Lightning strikes cause more deaths in Australia than snakebites do. However, snakes do kill thousands of people per year in certain rural, tropical areas of Africa and Asia. Venomous snakes are more common in these areas, and people may have limited access to medical care.

A person bitten by a venomous snake should seek medical help immediately. In most areas with venomous snakes, antivenin is available to treat snakebite victims. Nearly all people who receive treatment with antivenin survive. However, some people have allergic reactions to antivenin, so it must be given under proper medical supervision. For information on the treatment of snakebites, see Snakebite.

People are sometimes bitten when they accidentally step on a venomous snake. But most bites result from people trying to harm snakes. People should keep a safe distance from dangerous or unfamiliar snakes. Generally, snakes attack people only if they feel threatened.

The evolution of snakes

The earliest known snake fossils date from about 100 million years ago, during the time of the dinosaurs. However, the first snakes probably evolved millions of years earlier, possibly as early as 150 million years ago. Snake skeletons are delicate, and their fossils are difficult for scientists to discover and fully understand.

Snakes evolved from lizards. Many scientists think that snakes evolved from burrowing lizards that tunneled through the soil in search of food. The first snakes may have resembled such small, wormlike snakes as blind snakes. According to this theory, certain groups of snakes that evolved from these burrowing snakes later adapted to life above ground and in the water.

However, other scientists argue that snakes evolved from aquatic (water-dwelling) lizards. According to this theory, certain groups of snakes that evolved from aquatic snakes later adapted to life on land. Snake researchers must find additional and better-preserved fossils to fully determine the evolutionary history of snakes.

By the time the dinosaurs went extinct, about 65 million years ago, blind snakes, boas, pipe snakes, and other groups had become widespread. Many snake species went extinct during the Eocene Epoch, which ended about 34 million years ago. During the Oligocene Epoch, which lasted from about 34 million to 23 million years ago, a new group of snakes called colubrids evolved. The colubrids ultimately gave rise to hundreds of new species. In fact, more than half of modern snake species descend from colubrids.

Snakes, especially colubrids, became much more diverse during the Miocene Epoch, which began about 23 million years ago. In fact, some scientists refer to the Miocene as the Age of Snakes. The spread of small birds and mammals may have encouraged the evolution of snakes during this time. Such diversifying species would have provided many new sources of food for snakes, causing snakes in turn to diversify. Many venomous species evolved during this time, which provided new opportunities for snakes. Also, many snake species feed on other snakes, which might have contributed to diversification in both the predatory snake species and the hunted ones. Most modern snake groups had developed by the start of the Pliocene Epoch, about 5.3 million years ago.

Classification of snakes

There are thousands of snake species. They are classified into various families, based on how closely related they are. Not all scientists agree on the number and arrangement of snake families. Scientists continue to uncover new evidence that affects how snakes should be classified, and not all researchers agree on how to interpret this evidence. This section describes families that include most familiar snakes. It does not list all snake families. The scientific name of each family is given in parentheses after the common name.

Blind snakes

(Typhlopidae) burrow underground and eat mainly ants and termites. Blind snakes look much like earthworms, though some species may grow to more than 2 feet (60 centimeters) long. Their eyes are covered by head scales. Most live in tropical and subtropical regions. There are hundreds of species.

Boas

(Boidae) typically have large, stout bodies. The green anaconda can reach about 30 feet (9 meters) long. However, some boa species may grow less than 3 feet (90 centimeters) long. Most boas have external vestiges of hind legs, called spurs. Most boas live in tropical and subtropical regions. The different species may live on land, in trees, or in water. There are dozens of species.

Colubrids

(Colubridae) make up more than half of all species of snakes. The different species vary greatly in appearance and ways of life. The family includes most of the common harmless snakes, such as the North American garter snakes and rat snakes. It also includes many species of venomous, rear-fanged snakes. However, only a few rear-fanged snakes, such as the African bird snakes and boomslangs, are dangerous. Colubrids live throughout most of the world. They make their homes on land, in trees, in water, or underground.

Early blind snakes

(Anomalepididae, or Anomalepidae), also called primitive blind snakes, are small wormlike snakes that burrow on the floor of rain forests in Central and South America. They eat small invertebrates (animals without backbones). There are more than a dozen species.

Elapids

(Elapidae) are venomous snakes with short, fixed front fangs. Elapids are most diverse in Australia and nearby islands. Australian species include the black snakes, death adders, taipans, and tiger snakes. The cobras of Africa and Asia, the kraits of southern Asia, the mambas of Africa, and sea snakes are also elapids. There are dozens of species.

Homalopsids

(Homalopsidae), sometimes called rear-fanged water snakes, are aquatic snakes that live in Southeast Asia and Australia. They are venomous but are considered to pose little threat to humans. Traditionally, this group was placed in the colubrid family. There are dozens of species.

Pythons

(Pythonidae) are a group of mostly large snakes from Africa, Asia, and Australia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, from rain forests to dry scrub. Most species live on the ground, though some reside in trees or in water. Pythons eat a variety of vertebrates (animals with backbones), often including warm-blooded animals. Most species have heat-sensitive pits on their faces to locate prey. Some researchers place pythons in the boa family. There are dozens of species.

Shield-tailed snakes

(Uropeltidae) are burrowing snakes that live in Sri Lanka and southern India. They have a pointed or wedge-shaped snout; a short, blunt tail; and smooth scales. Most species live in the soils of humid mountain areas. There are dozens of species.

Slender blind snakes

(Leptotyphlopidae), also called worm snakes or thread snakes, resemble other families of blind snakes and have similar ways of life. Slender blind snakes live in Africa, southern Asia, and warm areas of North America and South America. There are dozens of species.

Vipers

(Viperidae) have hinged fangs attached to the front of the upper jaw. The fangs, which may be quite long, can move forward and backward. The Gaboon viper, or Gaboon adder, has perhaps the longest fangs of any snake. Its fangs can grow to about 2 inches (5 centimeters) long. There are hundreds of viper species.

The two largest groups of vipers are pit vipers and true vipers. Pit vipers have pit organs between their eyes and nostrils. They inhabit the Americas, Asia, and Europe. Pit vipers include rattlesnakes and moccasins. True vipers lack pit organs. They live in Africa, Asia, and Europe. True vipers include the Gaboon viper and carpet vipers, also called saw-scaled vipers.

Other snake families.

There are a number of other snake families with relatively few members. For example, Asian pipe snakes (Cylindrophiidae) are small to medium-sized burrowing snakes. File snakes (Acrochordidae) are aquatic snakes with a stout body and wrinkled skin. The pipe snake (Aniliidae), sometimes called the false coral snake, is a burrowing snake.