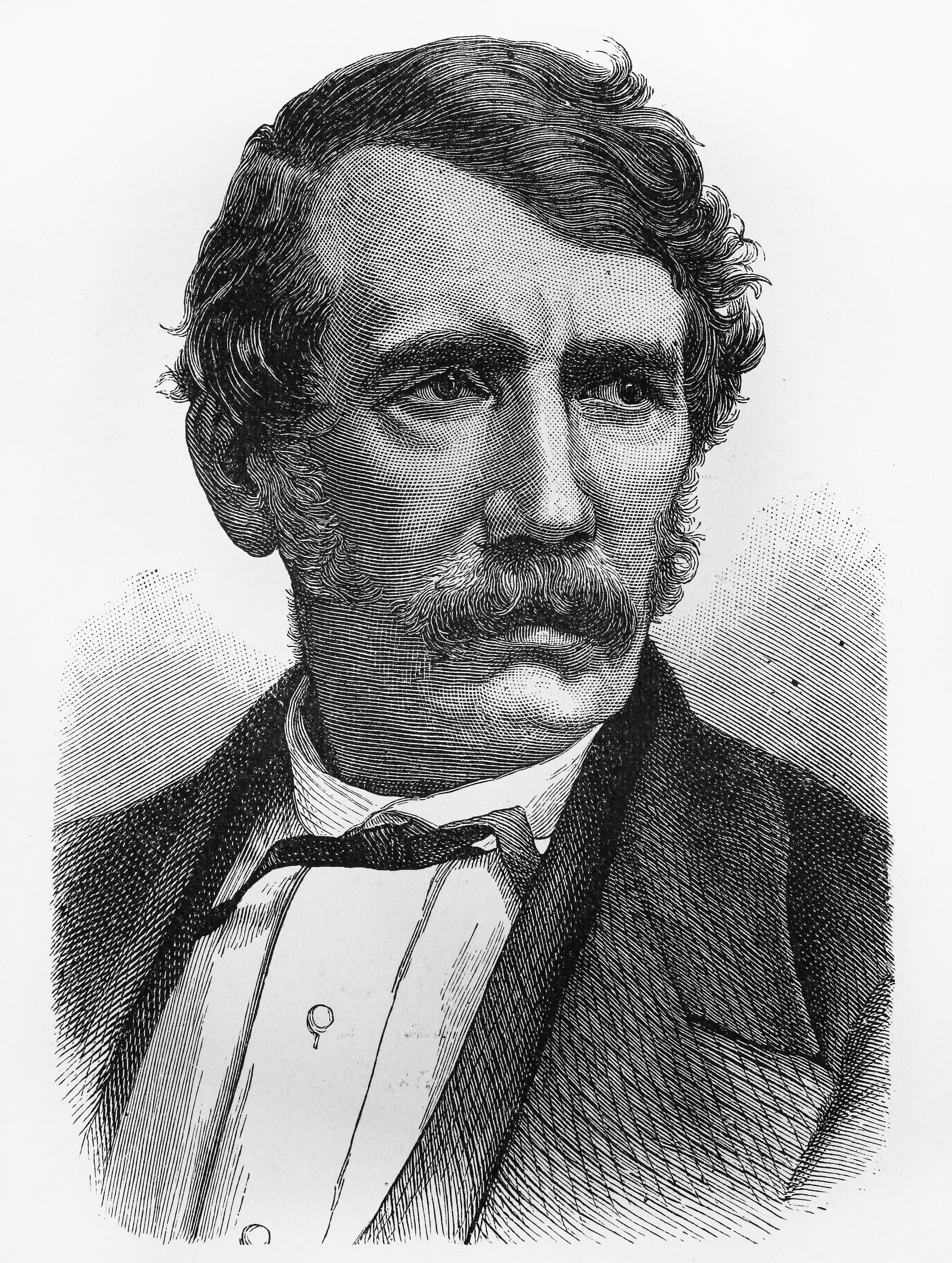

Stanley and Livingstone were two explorers whose travels in Africa excited the Western world and paved the way for Africa’s European colonization. David Livingstone (1813-1873) had captured the public’s imagination through his writings about his African explorations. But when he disappeared in the late 1860’s, rumors about his death began to circulate. In 1869, the New York Herald sent Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1904) to find him. In early November 1871, Stanley found Livingstone at the town of Ujiji, on Lake Tanganyika in east-central Africa. Stanley greeted him with the now-famous words: “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”

Livingstone’s discoveries.

David Livingstone was born on March 19, 1813, in Blantyre, Scotland, near Glasgow. He received a medical degree from the University of Glasgow. He later joined the London Missionary Society, which sent him to southern Africa in 1841. There he worked to convert Africans to Christianity and to end the business of selling Africans as slaves.

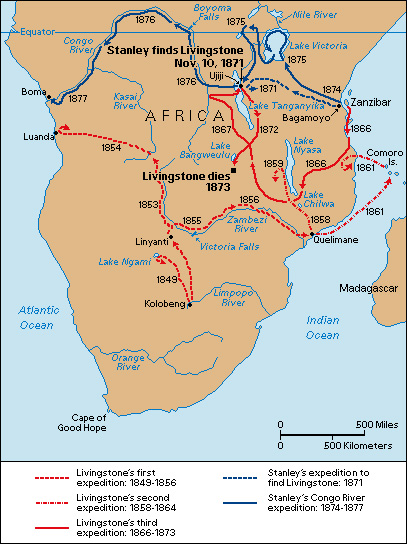

In 1849, Livingstone began to travel into Africa’s interior, mapping the land and searching for navigable rivers that British missionaries and traders could use. That year, he arrived at Lake Ngami, in what is now Botswana. In 1851, he traveled to the Zambezi River, on the border between present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Livingstone is famous for being the first European to cross Africa. But his trip, taken between 1853 and 1856, was financed and equipped by King Sekeletu of the Lozi Kingdom. On this trip, Livingstone started at the Zambezi and went northwest across Angola to Luanda on the Atlantic Ocean. On the return journey, he followed the Zambezi to its mouth in what is now Mozambique, where Portuguese officials treated him as a representative of Sekeletu. In 1855, he became the first European to sight what are now known as Victoria Falls on the Zambezi. He named the falls for Queen Victoria.

From 1858 to 1864, Livingstone led a large expedition, funded by the British government, across Africa’s interior. He became the first European to see Lakes Nyasa and Chilwa, in what is now Malawi. In 1866, Livingstone began to explore the Lake Tanganyika region. Livingstone believed that commerce and Christianity went hand in hand and enthusiastically depicted central Africa as a highly fertile region suitable for the production of sugar and cotton. His discoveries thus helped spark a great competition among European nations for control of Africa. He died on May 1, 1873, in what is now Zambia. His body was brought to London and buried in Westminster Abbey on April 18, 1874.

Stanley’s explorations.

Henry Morton Stanley was born on Jan. 28, 1841, in Denbigh, Wales, and was baptized John Rowlands. He spent most of his youth in a workhouse for orphans. At the age of 17, he sailed as a cabin boy on a ship to New Orleans. There, Henry Hope Stanley, a cotton dealer, adopted him. Stanley joined the Confederate Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865) and was soon captured. Stanley joined the Union Army to get out of prison but was discharged because of poor health. He joined the Union Navy in 1864.

In 1865, Stanley deserted and became a newspaper reporter. During the late 1860’s, he covered Indian wars in the American West and a British military campaign in Ethiopia. But his best-known assignment was to find Livingstone. He wrote about his journey in How I Found Livingstone (1872), a best-selling book.

After their meeting, Stanley became interested in Livingstone’s hope of finding a source of the Nile River south of the known source in Lake Victoria. Stanley postponed his plans to rush home with news of the great explorer and stayed with him until March 1872.

After Livingstone’s death, Stanley became a professional explorer. Although Stanley emphasized his friendship with Livingstone, he was more ruthless in dealing with the African communities he encountered on his journeys. In 1874, he led an expedition of about 350 people into Africa’s interior. The group explored Lake Victoria and other lakes, and followed the Congo River west to its mouth at the Atlantic Ocean. By 1877, over two-thirds of the group had died or deserted, and he left for England. Stanley‘s bold exploration and reputation for ruthlessness earned him the nickname Bula Matari (smasher of rocks) from the Africans he exploited.

From 1879 to 1884, Stanley, who had been hired by King Leopold II of Belgium, helped the king claim the Congo Free State, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1887, Leopold, with financing from English traders and the Royal Geographical Society, sent Stanley to the Sudanese province of Equatoria, prized for its trade routes and ivory stockpiles. Leopold and William Mackinnon, a Scottish businessman, portrayed Stanley’s journey as a mission to rescue Equatoria’s governor, Emin Pasha, but they secretly hoped to claim Equatoria.

The accounts of Stanley’s travels made him famous, and he served in the British Parliament from 1895 to 1900. He was knighted in 1899 and died on May 10, 1904.