Statue of Liberty is a majestic copper sculpture that towers above Liberty Island at the entrance to New York Harbor in Upper New York Bay. This famous figure of a robed woman holding a torch is one of the largest statues ever built. The statue’s complete name is Liberty Enlightening the World.

The people of France gave the Statue of Liberty to the people of the United States in 1884. This gift was an expression of friendship and of the ideal of liberty shared by both peoples. French citizens donated the money to build the statue, and people in the United States raised the funds to construct the foundation and the pedestal (base). The French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi designed the statue and chose its site.

The Statue of Liberty is a monumental feat of sculpture, engineering, and architecture. It attracts visitors from all over the world. The Statue of Liberty and a former immigration station at Ellis Island make up the Statue of Liberty National Monument, which is administered by the National Park Service.

The statue as a symbol

The Statue of Liberty has become a symbol of the United States and an expression of freedom to people throughout the world. The statue shows Liberty as a goddess draped in the graceful folds of a loose robe. In her uplifted right hand, she holds a glowing torch. She wears a crown with seven spikes that stand for the light of liberty shining on the seven seas and seven continents. With her left arm, she cradles a tablet bearing the date of the Declaration of Independence. A chain that represents tyranny (unjust rule) lies broken at her feet.

Loading the player...

Lazarus' The New Colossus

From the 1890’s to the 1920’s, many millions of immigrants passed the Statue of Liberty as they entered the United States. For them, the statue was a strong, welcoming figure holding out the promise of freedom and opportunity. The American poet Emma Lazarus expressed this idea of the statue as “Mother of Exiles” in a famous poem written in 1883. This poem, entitled “The New Colossus,” was inscribed on a bronze plaque placed on the interior wall of the pedestal of the monument in 1903. The poem reads:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame, With conquering limbs astride from land to land; Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame. “Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me. I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Description

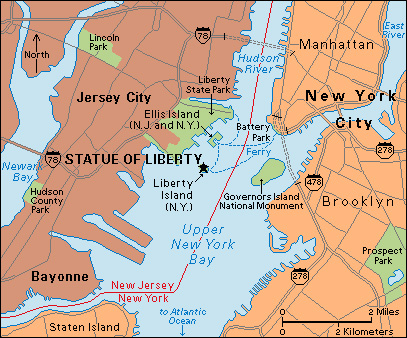

The Statue of Liberty stands on Liberty Island , a 12-acre (5-hectare) island in Upper New York Bay. The island lies about 11/2 miles (2.4 kilometers) southwest of the tip of Manhattan Island. The island was originally called Bedloe’s Island after Isaac Bedloe, a Dutch merchant who owned it in the late 1600’s. It came under federal jurisdiction after the Revolutionary War in America (1775-1783). The United States government completed construction of a star-shaped fort on the island in 1811 to defend New York against naval attack. The government later named the installation Fort Wood after Eleazar Wood, a hero of the Battle of Fort Erie during the War of 1812 (1812-1815). The statue’s pedestal rises from within the old fort’s walls. In 1956, the U.S. Congress changed the island’s name to Liberty Island.

The pedestal

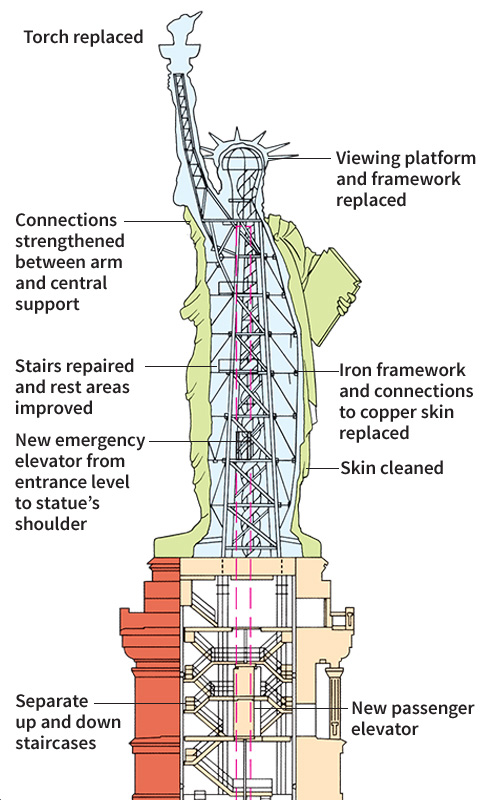

is an enormous mass of concrete reinforced with steel beams and covered with Connecticut granite. It was designed by Richard Morris Hunt, an American architect famous for designing magnificent mansions. The pedestal is 89 feet (27 meters) tall. It rests on a huge concrete foundation 65 feet (20 meters) tall. When the pedestal was completed in 1886, its foundation was the largest single concrete structure in the world. Stairs and a passenger elevator run up through the interior of the pedestal. Partway up the pedestal stands a row of pillars called a colonnade. A balcony extends around the top of the pedestal.

The statue

stands 151 feet 1 inch (46.05 meters) high from its feet to the top of the torch. It weighs 225 tons (204 metric tons). The figure consists of 300 sheets of Norwegian copper fastened together with rivets (threadless bolts). This copper skin is only 3/32 inch (2.4 millimeters) thick. Sculptor Auguste Bartholdi chose pure copper instead of an alloy (mixture) because it was lighter and it could be hammered thin. The statue is one of the most celebrated examples of repousse work, a process of shaping metal by hammering it into a mold.

Gustave Eiffel, the French engineer who later built the famous Eiffel Tower in Paris, designed the structural framework that supports the copper covering. The framework for the Statue of Liberty resembles what he later devised for the Eiffel Tower. It consists of a central tower of four vertical iron columns connected by horizontal and diagonal crossbeams. Iron girders leading up and out from the tower support the raised right arm.

Eiffel’s strong but flexible design enables the copper skin to react to wind and temperature changes without placing great stress on the statue’s framework. Iron bars extend from the central tower to stainless steel “ribs” that follow the shape of the statue’s inner surface. These ribs are not rigidly attached to the copper skin. Instead, they fit into special copper brackets connected to the inside of the skin. This indirect method of attaching the copper skin to the ribs enables the statue to absorb the force of the strong winds that often blow across the bay. The attachment method also allows the copper skin to expand and contract as the temperature rises and falls.

Two parallel, spiral stairways wind up through the interior of the statue to the crown on the statue’s head. A small elevator runs from the ground level in the base to the shoulder level of the statue. The elevator is used only in emergencies or for maintenance of the statue.

The torch towers 305 feet 1 inch (92.99 meters) above the base of the monument. At night, its gold-covered flame glows with reflected light from 16 powerful lamps arranged around the rim of the torch. Lamps shining up from below illuminate the rest of the statue.

History

Inspiration and preparations.

The idea for the statue came from Edouard Laboulaye, a prominent French politician and historian. Laboulaye greatly admired the United States. At a dinner party in 1865, after the end of the American Civil War, he proposed the construction of a joint French and American monument celebrating the ideal of liberty.

In 1871, Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, Laboulaye’s friend and a noted French sculptor, sailed to the United States to seek support for the project. During his trip, Bartholdi selected Bedloe’s Island, in Upper New York Bay, as the site for the monument.

Upon returning to France, Bartholdi began designing the statue. In the late 1860’s, he had proposed a lighthouse for the newly constructed Suez Canal in Egypt. He had suggested a colossal sculpture of a woman bearing a torch, to be called Egypt (or Progress) Bringing the Light to Asia. That project was never built. For the monument to liberty, Bartholdi planned a similar sculpture that would be the largest built since ancient times. He modeled the figure’s face after the face of his mother.

In 1875, the French-American Union was established to raise funds and oversee the project. Laboulaye became chairman of the organization in France. The French people donated about $400,000 for the construction of the statue. In 1877, the American Committee was organized in the United States to raise funds needed to build the pedestal. In 1881, the American architect Richard Morris Hunt was selected to design the pedestal. Hunt had studied architecture in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, a famous school of fine arts. He had designed many mansions for rich families in New York City and Newport, Rhode Island. He planned a massive pedestal of concrete, granite, and steel that would not detract attention from the statue.

Construction and dedication.

Construction of the statue began in 1875 at a workshop in Paris. First, Bartholdi built a small clay model of the figure. Then the sculptor and his assistants built three plaster models, each larger than the previous one. For the final version, workers made a strong wooden framework for each major section of the statue. A layer of plaster was then applied over this wooden framework, forming a full-scale model for each major part of the figure.

Next, carpenters built large wooden forms that followed the shape of the plaster model of the statue. Metalworkers then placed thin sheets of copper in the wooden forms. They bent the copper sheets and hammered them into the shape of the forms. When the hammered copper sheets were removed from the forms, they matched the shape of the plaster model from which the wooden forms had been made.

Designing a framework to support the statue presented a difficult engineering challenge. French engineer Gustave Eiffel devised a support system with a central iron tower. A strong but flexible framework of iron bars would connect the copper skin to the tower. Eiffel’s support system was erected outside the Paris workshop where the statue was being made. Then workers attached the sections of copper skin to the framework.

Bartholdi had hoped to present the statue to the United States on July 4, 1876—the centennial of the Declaration of Independence. But a late start and subsequent delays made this impossible. He had completed the right hand and torch by 1876, however, and sent this section of the statue to the United States. It was displayed at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and later shown in New York City before it was returned to Paris. In 1878, an international exposition in Paris displayed Liberty’s head. The people of France officially presented the entire statue to the U.S. minister to France in Paris on July 4, 1884.

Construction of the pedestal began in 1884 but soon came to a halt because of a lack of funds. In March 1885, Joseph Pulitzer, the new publisher of a New York newspaper called The World, launched a front-page campaign to raise funds for the completion of the pedestal. By mid-August, about 121,000 people had contributed a total of more than $100,000—enough to finish building the pedestal. Pulitzer listed every contributor’s name in his paper, which greatly boosted sales of The World. The pedestal was completed in April 1886, at a final cost of about $300,000.

Meanwhile, the statue had been disassembled in Paris and packed in 214 wooden crates for shipment to the United States. The French ship Isere carried the statue across the Atlantic Ocean and arrived at New York City on June 17, 1885. Assembly of the statue began soon after the pedestal was completed.

On Oct. 28, 1886, Liberty Enlightening the World was dedicated in Upper New York Bay. New York City celebrated with a grand parade, and boats filled the harbor. United States President Grover Cleveland and members of his Cabinet attended the ceremonies. Bartholdi and representatives of the French government and the French-American Union also participated.

Growth as a symbol.

The Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886 as a memorial to the alliance between France and the American colonists who fought for independence in the Revolutionary War in America. It also served as a symbol of the friendship between France and the United States. Over the years, however, it has taken on additional meanings. Bartholdi, aware of his statue’s commercial potential as an image, had copyrighted it in both France and the United States. But even by 1886, he found himself powerless to enforce his rights. The statue’s image came to be used in countless advertisements, campaigns, and trademarks.

During World War I (1914-1918), the Statue of Liberty became a powerful symbol of the United States. The statue’s image appeared on posters for war bonds sold by the U.S. Treasury. Sales of these bonds, called Liberty Bonds, raised about $15 billion and helped pay for the cost of the war. As the statue gained in popularity, its formal title, Liberty Enlightening the World, was replaced in common usage by the name Statue of Liberty.

From the 1890’s to the 1920’s, many millions of immigrants passed the Statue of Liberty as they entered the United States at Ellis Island. Increasingly, newcomers looked upon the statue as a welcoming presence. In 1903, a plaque with Emma Lazarus’s poem, “The New Colossus,” had been placed on an interior wall of the pedestal of the statue. But it was not until a second wave of immigrants arrived after World War II (1939-1945), that the statue became popularly linked with the poem’s image of the “Mother of Exiles.”

Repairs and changes.

Bartholdi had intended the Statue of Liberty to serve as a lighthouse, with kerosene lamps burning in the crown. Before the statue was dedicated, however, officials decided to light the torch instead. They had electric lights installed that shone through two rows of windows cut in the flame. The federal lighthouse board administered the Statue of Liberty from 1886 to 1902. But the light from the torch was too dim to serve as an effective beacon. In 1902, the U.S. War Department, which administered Fort Wood, took over responsibility for the statue.

In 1916, the War Department installed floodlights at the base of the statue and changed the torch lighting system. Visitors were no longer allowed in the torch or on the torch’s observation deck. Hundreds of windows were cut in the copper flame of the torch, and powerful lamps inside lit the torch.

In 1924, the Statue of Liberty became a national monument. The National Park Service took over responsibility for maintaining the statue in 1933.

By the early 1980’s, the Statue of Liberty required major repairs. A group of engineers and friends of the monument formed the French-American Committee for Restoration of the Statue of Liberty. In cooperation with the National Park Service, the committee inspected the statue and planned a $30-million restoration project. However, the final cost of the restoration totaled more than twice that amount. Private donations to the Statue of Liberty—Ellis Island Foundation raised the funds. The foundation also set out to raise $160 million to restore the immigration station at Ellis Island.

For two and a half years, while the restoration work went on, aluminum scaffolding hid the statue. During the original assembly process, the workers had used no scaffolding, only ropes. A major part of the restoration was the replacement of the torch. Restorers removed the old torch and fashioned a new one, duplicating Bartholdi’s original design and construction methods. The new torch has no windows. Its flame is covered with gold leaf and glows with reflected light. The old torch now stands on display in the lobby of the pedestal.

When the statue was erected in 1886, workers did not attach the statue’s head and right arm to the framework in the right place. Instead, they attached the head and arm about 2 feet (60 centimeters) to the right of where Eiffel had planned their attachment. This caused a weak connection at the right shoulder. The restoration strengthened this connection.

The restoration also included replacing the statue’s many ribs that link the skin to the frame. The original ribs were made of iron, and many had rusted badly. Restoration workers shaped new stainless steel ribs to replace those made of iron. Workers also replaced many rivets that had pulled loose from the copper skin.

Cleaning crews carefully removed stains from the exterior of the statue but preserved the familiar greenish color of the exposed copper. In fact, the restorers coated any copper they added to match the existing copper. The cleaning also stripped layers of dirt, paint, and tar from the inside.

The Park Service installed a new passenger elevator in the pedestal and added an emergency elevator that reaches to the shoulder level. The restoration also improved the ventilation system and installed a new lighting system. Landscapers redesigned the plantings around the monument to provide a new approach from the ferry landing. New doors were installed at the entrance in the statue’s base.

Official celebrations marked the opening of the newly restored Statue of Liberty on July 4, 1986, with President Ronald Reagan and an audience of 2 million people in attendance. Another grand ceremony took place on Oct. 28, 1986—100 years after the original dedication.

The early 2000’s.

On Sept. 11, 2001, the United States experienced the worst terrorist attacks in the nation’s history. About 3,000 people were killed, and the World Trade Center towers in New York City and part of the Pentagon Building, near Washington, D.C., were destroyed (see September 11 terrorist attacks). After these attacks, the Statue of Liberty and other important symbols of the United States were closed to the public until increased security measures could be put in place.

Until September 11, visitors had been free to climb the staircase inside the Statue of Liberty and look out a window from an observation deck in the crown. For three months after the events of September 11, visitors were not allowed on Liberty Island. On Dec. 20, 2001, ferry rides to the island began again. However, the statue itself remained closed while new fire-alarm systems were installed and other changes were made for the protection of visitors and the monument.

Officials reopened the Statue of Liberty in the summer of 2004. Visitors can go inside the pedestal and up to an observation area at the top of the pedestal. There, they can view the harbor and look up through a glass ceiling to see the statue’s interior. The crown reopened to visitors on July 4, 2009.