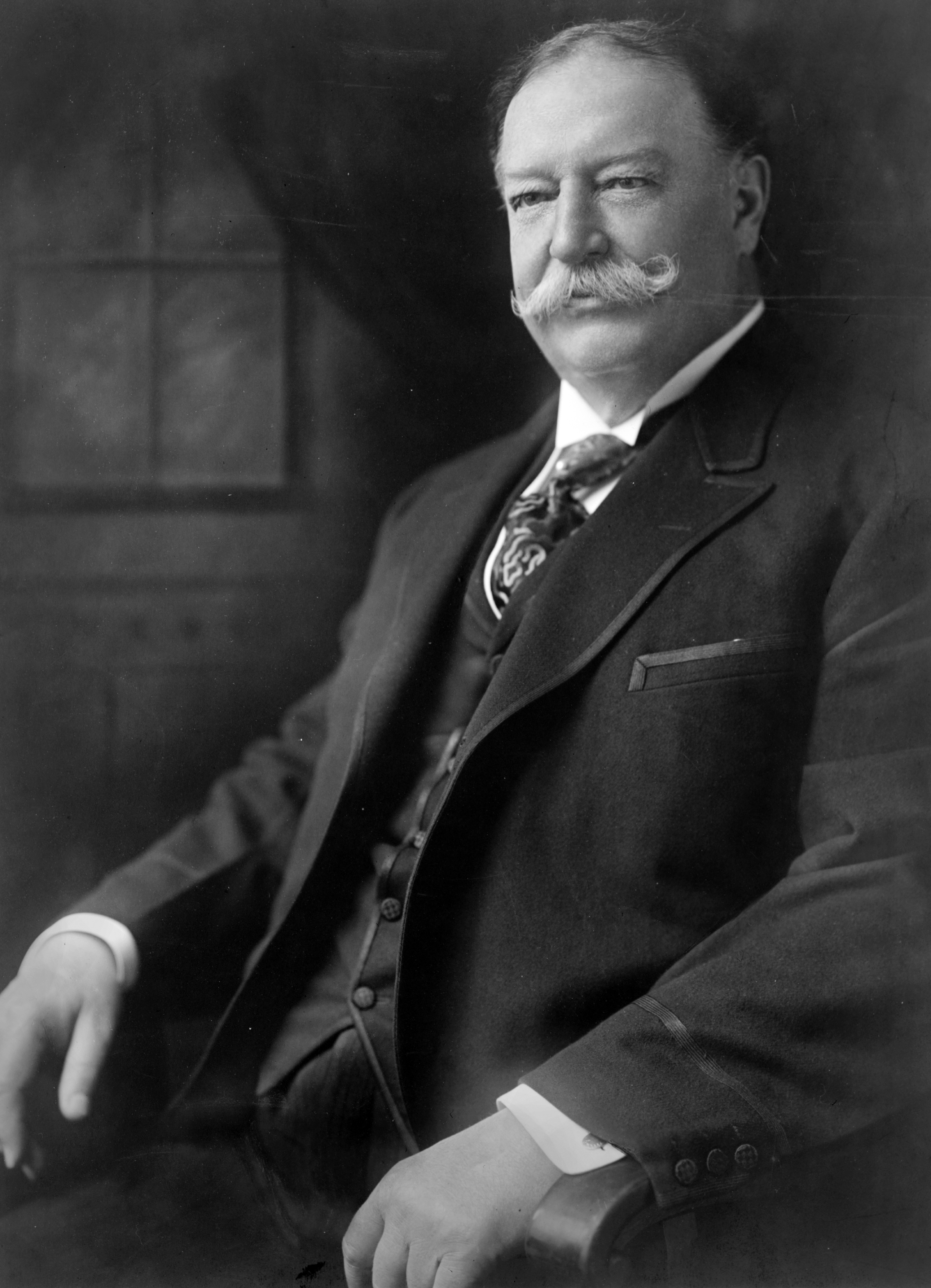

Taft, William Howard (1857-1930), was president of the United States from 1909 to 1913. In 1921, he was named chief justice of the United States. He was the only person in U.S. history who served first as president, then as chief justice. Taft did not want to be president. At heart, he was a judge and had little taste for politics. Above all, he wanted to be a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

Before becoming president, Taft, a Republican, served as governor of the Philippines and as U.S. secretary of war under President Theodore Roosevelt. However, Taft spent most of the first 20 years of his career as a lawyer and judge. His mother recognized his distaste for politics. “I do not want my son to be president,” she said. “His is a judicial mind and he loves the law.” But Taft’s wife opposed his career as a judge because she felt it was a “fixed groove.”

In the end, Taft’s mother proved to be right. Hardly any other president has been so unhappy in office. When Taft left the White House in 1913, he told incoming President Woodrow Wilson: “I’m glad to be going. This is the lonesomest place in the world.” When he was appointed chief justice of the United States eight years later, Taft said it was the highest honor he ever received. He wrote: “The truth is that in my present life I don’t remember that I ever was president.”

Taft was the largest person ever to serve as president. He stood 6 feet (183 centimeters) tall and weighed more than 300 pounds (136 kilograms). A newspaperman wrote that he looked “like an American bison—a gentle, kind one.” Taft had a mild, pleasant personality, but he clung firmly to what he considered the rugged virtues. He did not smoke or drink. He was honest by nature, plain of speech, and straightforward in action. He was completely, and sometimes blindly, loyal to his friends and to his political party.

The modest Taft felt he was not fully qualified for the presidency. He had no gift of showmanship like his predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt. Taft gave the public an adequate administration, but he failed to capture popular imagination. Many people called him a failure as president.

Early life

William Howard Taft was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Sept. 15, 1857. He was the second son of Alphonso Taft and Alphonso’s second wife, Louise Maria Torrey Taft.

Alphonso Taft’s ancestors had lived in Massachusetts and Vermont since emigrating from England in the 1600’s. His wife was descended from an English family that helped settle Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1640. Alphonso Taft, whose father was a Vermont judge, moved to Cincinnati about 1838. He became a successful lawyer and a nationally prominent figure in the Republican Party.

Will Taft was a large, fair, and attractive youth. He was brought up in the Unitarian faith. Two older half brothers, two younger brothers, and a younger sister were his playmates. They called Taft “Big Lub” because of his size. During the summers, the five Taft boys visited their Grandfather Torrey in Millbury, Massachusetts. He made them cut wood in his wood lot to pay for their vacations, and also to teach them the value of money.

When Taft was 13 years old, he entered Woodward High School in Cincinnati. At 17, he enrolled in Yale College. In 1878, Taft graduated second in his class. He then studied law at the Cincinnati Law School. He received a law degree in 1880 and was admitted to the Ohio bar.

Political and public career

First offices.

During 1881 and 1882, Taft served as assistant prosecuting attorney of Hamilton County, Ohio. In March 1882, President Chester A. Arthur appointed him collector of internal revenue for the first district, with headquarters at Cincinnati. Taft resigned a year later because he did not want to discharge good workers just to make jobs for deserving Republicans. He then formed a successful law partnership.

Taft’s family.

On June 19, 1886, Taft married Helen “Nellie” Herron (June 2, 1861-May 22, 1943), the daughter of John W. Herron of Cincinnati. Herron had been a law partner of President Rutherford B. Hayes. Taft wrote that his wife was “a woman who is willing to take me as I am, for better or for worse.” Mrs. Taft was both intelligent and ambitious. Throughout her husband’s career, she encouraged him to seek public office.

The Tafts had three children. Robert Alphonso Taft (1889-1953) became a famous U.S. senator from Ohio and a leader of the Republican Party. Helen Herron Taft Manning (1891-1987) served as professor of history and dean of Bryn Mawr College in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Charles Phelps Taft II (1897-1983), a lawyer, was mayor of Cincinnati from 1955 to 1957.

State judge.

Taft was happy as a lawyer, but his father’s importance in the Republican Party kept pushing him toward political life. Early in 1885, Taft was named assistant county solicitor for Hamilton County. In March 1887, Governor J. B. Foraker of Ohio appointed him to a vacancy on the Cincinnati Superior Court. The next year, the voters elected Taft to the court for a five-year term. This was the only office except the presidency that Taft won by popular vote.

Solicitor general.

Taft resigned from the Cincinnati Superior Court in 1890 to accept an appointment by President Benjamin Harrison as solicitor general of the United States. During his first year, he won 15 of the 18 government cases that he argued before the Supreme Court.

Federal judge.

In March 1892, President Harrison appointed Taft a judge of the sixth circuit of the newly established United States Circuit Court of Appeals (now the United States Court of Appeals). Taft spent the next eight years as a circuit judge. From 1896 to 1900, he also was dean of the University of Cincinnati Law School.

Governor of the Philippines.

In 1900, President William McKinley appointed Taft chairman of a civil commission to govern the newly acquired Philippines. The next year Taft was named the first civil governor of the islands.

Taft’s career in the Philippines was an example of the best in colonial government. He established new systems of courts, land records, vital and social statistics, and sanitary regulations. He built roads and harbors, worked toward the establishment of limited self-government, and led a movement for land reform. Taft also established schools in many areas and worked steadily to improve the economic status of the people.

Taft ardently desired to be a justice of the Supreme Court. But in 1902, he turned down his first chance for appointment to the court because he felt he had not finished his work in the Philippines.

Secretary of war.

Secretary of War Elihu Root resigned in February 1904. Taft returned to Washington to assume this post in President Theodore Roosevelt’s Cabinet. Taft’s appointment was good politics. The 1904 presidential campaign was approaching, and Taft had won great popularity for his work in the Philippines.

The president soon began using Taft as his unofficial troubleshooter, both at home and abroad. Roosevelt continued to do so after winning the 1904 election. Taft’s department supervised the construction of the Panama Canal and set up the government in the Canal Zone. Taft himself advanced Roosevelt’s tariff policy and assisted the president in negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth, which ended the Russo-Japanese War. Everything was all right in Washington, the president said, because Taft was “sitting on the lid.”

Election of 1908.

Roosevelt announced he would not seek reelection in 1908, and recommended Taft as the man who would follow his policies. At first, Taft objected, preferring to wait for possible appointment to the Supreme Court. But Mrs. Taft and his brothers helped change his mind.

With Roosevelt’s support, Taft won the nomination on the first ballot at the Republican National Convention, which was held in Chicago. Representative James S. Sherman of New York received the vice presidential nomination. In the election, the voters gave Taft a plurality of more than a million votes over William Jennings Bryan, who suffered his third loss as Democratic nominee for president. Bryan shared the Democratic ticket with John W. Kern, a Democratic Party leader of Indiana.

Taft’s administration (1909-1913)

“Even the elements do protest,” said Taft unhappily when a blizzard swept Washington on the morning of his inauguration in March 1909. From the start, Taft was filled with doubt about being president. He knew he could not be another Roosevelt. “There is no use trying to be William Howard Taft with Roosevelt’s ways,” he remarked. “Our ways are different.” Taft decided to “complete and perfect the machinery” with which Roosevelt had tried to solve the problems of the United States.

Legislative defeats.

Taft began his term with a divided party, although the Republicans controlled both houses of Congress. On the advice of Roosevelt, Taft refused to support the liberal Republicans in their fight to curb the almost unrestricted powers of the Speaker of the House, Joseph “Uncle Joe” Cannon of Illinois. But these Republicans, led by Representative George W. Norris of Nebraska, overthrew “Cannonism.” Because of his political inexperience in this and other matters, Taft soon lost the support of most liberal Republicans.

Like many other Americans, Taft believed in tariff protection. But he also felt that somewhat lower tariffs would help control trusts. He called Congress into special session to pass a tariff-reduction law but was reluctant to impose his ideas on Congress. The House passed a bill with big reductions. But in the Senate, Nelson W. Aldrich of Rhode Island, one of Taft’s chief advisers, led the campaign to keep high tariffs. The resulting law, the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, lowered some tariff rates slightly but left the general level of rates as high as they had been. Taft said he knew he “could make a lot of cheap popularity by vetoing the bill.” Instead, he accepted it as better than nothing, defended it in public, and suffered from the great unpopularity that the bill received.

Taft further antagonized the liberal Republicans by his stand in the Pinchot case. In late 1909, Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot made sensational charges that the Department of the Interior, and especially Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger, had abandoned the conservation policies of Theodore Roosevelt. Pinchot also accused the department of selling land concessions to water and power companies too cheaply and of illegal transactions in the sale of Alaska coal lands. Taft upheld Ballinger, who was later cleared by a congressional investigating committee. Taft then dismissed Pinchot. Liberal Republicans became convinced that some of Pinchot’s charges were true, and they began to turn to Roosevelt as their true leader.

Legislative achievements

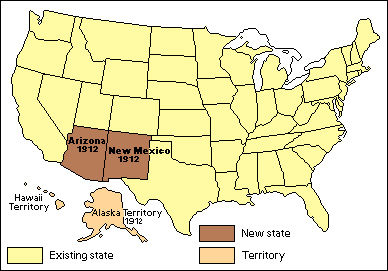

of the Taft administration included the first scientific investigation of tariff rates, for which the president established the Tariff Board. Taft took the first steps toward establishing a federal budget by asking his Cabinet members and their staffs to submit detailed reports of their financial needs. Congress created the Postal Savings System in 1910 and parcel post in 1913. At Taft’s request, Congress also organized a commerce court and enlarged the powers of the Interstate Commerce Commission. The president pushed a bill through Congress requiring that campaign expenses in federal elections be made public. During Taft’s administration, Alaska received full territorial government, and the Federal Children’s Bureau was established. The president took action against many trusts. Nearly twice as many “trust-busting” prosecutions for violation of the Sherman Antitrust Act took place during Taft’s four years in office as had occurred during Roosevelt’s administration of almost eight years.

Foreign affairs.

The Taft administration had an uneven record in international relations. During the late 1800’s, nations customarily used diplomacy to expand their commercial interests. “Dollar diplomacy,” as promoted by Secretary of State Philander C. Knox, had just the opposite purpose. To Knox, it meant the use of trade and commerce to increase a nation’s diplomatic influence. The United States made loans to China, Nicaragua, Honduras, and other countries in order to encourage investments by bankers in loans to these nations. Taft ended the second American occupation of Cuba in 1909 and negotiated treaties of arbitration with the United Kingdom and France. These treaties ranked as landmarks in the effort of nations to settle their differences peacefully, but the Senate rejected them.

Life in the White House.

Mrs. Taft, a skillful hostess, enjoyed presiding at state functions and entertaining friends at small teas. She hired a woman to replace the traditional male steward because she thought the service would be improved. At Mrs. Taft’s request, the mayor of Tokyo presented about 3,000 cherry trees to the American people. The trees were planted along the banks of the Potomac River.

Mrs. Taft suffered a stroke in the winter of 1909. Thereafter, her daughter, Helen, or her sister, Mrs. Louis More, often acted as Taft’s official hostess. Mrs. Taft had a better head for politics than did her husband. Taft relied on his wife’s judgment and missed her help after she became ill.

On summer evenings, the Tafts often sat on the south portico of the White House and listened to favorite phonograph recordings. Taft was an excellent dancer, and Mrs. Taft organized a small dancing class for his diversion. He played tennis and golf well and often rode horseback.

Election of 1912.

Theodore Roosevelt had returned in 1910 from an African hunting trip. He denied an interest in running for the presidency again but began making speeches advocating a “New Nationalism.” Under this slogan, Roosevelt included his old policies of honest government, checks on big business, and conservation, as well as demands for social justice, including old-age and unemployment insurance. Conservative Republicans lined up with Taft against Roosevelt.

Although Roosevelt won most of the primary elections, a majority of the delegates to the nominating convention were pledged to Taft. The president was renominated on the first ballot, and James S. Sherman was renominated as vice president.

Roosevelt and the progressive Republicans accused Taft of “stealing” the convention by recognizing the votes of pro-Taft delegations. They organized the Progressive Party with Roosevelt as their nominee and chose Senator Hiram W. Johnson of California as his running mate. The Democrats nominated Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey for president and Governor Thomas R. Marshall of Indiana for vice president.

Taft faced inevitable defeat. He received only 8 electoral votes, against 88 for Roosevelt and 435 for Wilson.

Later years

Law professor.

After Taft left the White House in March 1913, he became professor of constitutional law at Yale University. That same year, he was elected president of the American Bar Association. During World War I (1914-1918), President Wilson appointed Taft joint chairman of the National War Labor Board.

During the war, Taft also headed the League to Enforce Peace. The organization recommended the formation of a league of nations that could work to prevent future wars. Taft became the leading Republican to support such a league, and he cooperated with President Wilson in promoting the idea. Wilson became the chief planner of the League of Nations.

Chief justice.

In 1921, President Warren G. Harding appointed Taft chief justice of the United States. Taft regarded this appointment as the greatest honor of his life. His accomplishments as administrator of the nation’s highest court were more important than his decisions. The Supreme Court had fallen far behind in its work. In 1925, Taft achieved passage of the Judiciary Act. This law gave the court greater control over the number and kinds of cases it would consider and made it possible for the court to function effectively and get its work done. Taft was also instrumental in obtaining congressional approval for a new court building.

Taft performed more than his share of the court’s great workload and often advised President Calvin Coolidge. He watched his health and held his weight to about 300 pounds (136 kilograms). Taft became a familiar figure in Washington as he walked the 3 miles (5 kilometers) between his home and the court almost every morning and evening. But finally the strain of overwork became too great. Bad health, chiefly due to heart trouble, forced his retirement on Feb. 3, 1930. Taft died on March 8 and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Taft and President John F. Kennedy are the only presidents buried there.