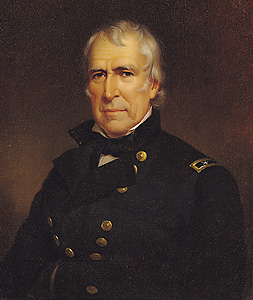

Taylor, Zachary (1784-1850), served his country for 40 years as a soldier and for 16 months as president. His courage and ability during the Mexican War made him a national hero. Taylor showed the same courage while he was president, but he died before he could prove his full abilities as a statesman. He was succeeded by Vice President Millard Fillmore.

President Taylor was one of the large slaveowners of the South. But he did not oppose admitting California and New Mexico to the Union as free states. The South demanded that other slavery problems be settled before those territories became states, and threatened to secede. Taylor replied that he was ready to take his place at the head of the army to put down any such action. He died at the height of this argument. President Fillmore’s policies delayed the American Civil War for 10 years.

Taylor made his greatest contribution to his country as a soldier. This quiet, friendly man was not a military genius but was a good leader. He never lost a battle. His troops nicknamed him “Old Rough and Ready.”

Early life

Childhood.

Zachary Taylor was born near Barboursville, Virginia, on Nov. 24, 1784. He was the third son in a family of six boys and three girls. His parents, Richard and Sarah Strother Taylor, came from leading families of the Virginia plantation region. Richard Taylor served as an officer in the Revolutionary War. In 1783, he received a war bonus of 6,000 acres (2,400 hectares) of land near Louisville, Kentucky. He settled there in 1785.

There were no schools on the Kentucky frontier, but Zachary studied for a while under tutors, and gained practical knowledge by working on his father’s farm.

Perhaps it was natural that Zachary should turn to a military career. He grew up in the midst of Indian warfare, and heard tales of the Revolutionary War from his father. In 1808, he was appointed a first lieutenant in the U.S. Army. In 1810, he was promoted to captain.

Taylor’s family.

Early in 1810, Taylor met Margaret Mackall Smith (Sept. 21, 1788–Aug. 14, 1852). She was the orphaned daughter of a Maryland planter. Taylor and Smith were married on June 21, 1810. They had a son and five daughters, two of whom died as infants. Their daughter Sarah married Jefferson Davis, the future president of the Confederacy. She died three months after her wedding. The Taylors’ son, Richard, served as a general in the Confederate Army.

Military career

Indian campaigns.

During the War of 1812, Taylor won promotion to major for his defense of Fort Harrison in the Indiana Territory. In 1819, he became a lieutenant colonel. He served in Wisconsin during the Black Hawk War and received the surrender of the Sauk Indian leader Black Hawk in 1832 (see Black Hawk ).

Taylor was sent to Florida in 1837. There he defeated the Seminole Indians at Lake Okeechobee on Dec. 25, 1837. This victory brought him the honorary rank of brigadier general. In 1841, Taylor became commander of the second department of the western division of the U.S. Army, with headquarters at Fort Smith, Arkansas.

Mexican War.

In 1846, Mexico threatened war with the United States over the annexation of Texas. Taylor was ordered to the Rio Grande with about 4,000 troops. Mexico considered this advance an invasion, and Mexican forces crossed the river to drive off the Americans. Taylor defeated them in battles at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. The United States declared war on May 13, 1846. Taylor then advanced into Mexico and captured Matamoros and Monterrey.

After these victories, Taylor seemed the obvious choice to lead an invading army into the central valley of Mexico. But President James K. Polk, a Democrat, knew that Taylor favored the rival Whig Party. Because Polk feared the growth of a popular Whig leader, he named General Winfield Scott to lead the campaign.

On Feb. 22-23, 1847, before Scott’s army departed, Taylor’s army of about 5,000 was attacked by between 16,000 and 20,000 Mexican troops in the Battle of Buena Vista. Taylor’s troops won a stunning victory over the forces of General Santa Anna. The triumph was due more to the skill and vigor of Taylor’s officers than to his generalship, but the victory made Taylor a national hero. See Mexican War ; Santa Anna, Antonio López de .

Nomination for president

Many Whig leaders, especially in the South, believed Taylor could easily win the presidency because of his military fame. Taylor hesitated to enter politics, but the Whigs nominated him anyway. They chose Millard Fillmore, comptroller of New York, for vice president. The Democrats nominated Senator Lewis Cass of Michigan and General William O. Butler of Kentucky.

During the campaign, both Whigs and Democrats took a two-sided stand on the divisive issue of slavery, seeming to favor it at one time and oppose it at other times. Only the Free Soil Party, led by former President Martin Van Buren, campaigned to ban slavery in the newly acquired Mexican territories (see Free Soil Party ). Van Buren did not carry a single state, but he drew many votes from Cass. Taylor and Fillmore won by 36 electoral votes. The presidential election of 1848 was the first held at the same time in all the states.

Taylor’s administration (1849-1850)

Taylor was inaugurated on March 5, 1849. He would normally have taken office on March 4, but declined to be inaugurated on Sunday. Some historians claim that David R. Atchison, president pro tempore of the Senate, served as acting president on March 4 because the presidency was vacant on that day.

Taylor relied on the advice of other people because he knew that he lacked political experience. However, no one could influence him to act against his conscience.

Life in the White House.

Mrs. Taylor had not favored the idea of her husband running for president. She viewed it as a plot to deprive her of his company. Mrs. Taylor, a semi-invalid, took little part in the White House social life. Hostess duties passed to her daughter Mary Elizabeth, known as Betty. Betty’s husband, Colonel William W. S. Bliss, served as Taylor’s secretary.

The Nicaragua Canal.

The acquisition of territory on the Pacific Coast during President James K. Polk’s administration revived the dream of a water route across Central America. American businessmen tried to obtain rights to build a canal across Nicaragua. The British were also interested in such a canal. In 1850, the United States and the United Kingdom signed the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty, which guaranteed the neutrality of any such canal. See Clayton-Bulwer Treaty .

Sectional quarrels.

Controversy over the extension of slavery in new territories reached a new high in 1849 as California prepared to apply for admission to the Union as a free state. Taylor urged Congress to admit California and New Mexico immediately as states rather than make them territories first. In this manner, he hoped to avoid the dispute over slavery in the territories. But Southerners angrily demanded the adjustment of other slavery problems before new states were admitted to the Union. During the next months, Congress had one of its greatest debates. Southerners threatened secession, and Northerners promised war in order to preserve the Union. Though he owned many slaves, Taylor sided with the North. He pledged to use force to uphold the Union.

Numerous congressional leaders, including Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, urged compromise. However, Taylor scorned any compromise, and insisted that California be admitted to the Union. Supporters of compromise eventually won, but not until Fillmore had succeeded to the presidency. Congress then adopted laws referred to as the Compromise of 1850. See Compromise of 1850 .

Death.

Before the slavery issue could be settled, Taylor became ill and died on July 9, 1850. He was buried in the family cemetery near Louisville, Kentucky. Mrs. Taylor died on Aug. 14, 1852, and was buried beside her husband.

In 1991, a team of experts examined President Taylor’s body to determine whether he had been assassinated by poisoning. They concluded that he died of natural causes.