Telegraph was an important means of communication from the mid-1800’s to the mid-1900’s. The telegraph was the first instrument used to send messages by means of wires and electric current. Telegraph operators sent signals using a device that interrupted the flow of electric current along a wire. They used shorter and longer bursts of current, with spaces in between, to represent the letters of the message in what became known as Morse code. A device at the receiving end converted the signals to a series of clicks that a telegraph operator or a mechanical printer translated into words. The message was called a telegram if it was sent over wires stretched across land and a cablegram, or simply a cable, if it was sent through cables laid underwater.

Loading the player...Morse code

Today, the original telegraph technology is rarely used. The telephone took the place of the telegraph for many uses. Other modern forms of communication, such as e-mail and fax, can transmit more information more quickly than the telegraph could. Certain telegraph services still survive, however, though the means of sending messages differ from the original technology. Messages now begin and end in computers, and they travel great distances by fiber-optic cable, radio, satellites, and other means of transmission.

Development of the telegraph

Before the telegraph, most long-distance messages traveled no faster than the fastest horse. An exception was the semaphore method, in which a sequence of lights or other markers signaled from point to point. However, semaphore systems did not work well at night or in bad weather. Even in good weather, they could transmit only a small amount of information.

Early discoveries.

The path to the telegraph began with discoveries that showed how electric current could be produced. In the 1780’s, the Italian physician Luigi Galvani conducted experiments in animal physiology in which he unknowingly discovered galvanism—that is, the production of an electric current from two metals in contact with a moist environment. In the late 1790’s, the Italian scientist Alessandro Volta used galvanism to create the first practical battery.

In 1820, Hans Christian Oersted, a Danish physicist, discovered that an electric current will cause a magnetized needle to move. This discovery about the relationship between electric currents and magnetism made possible the invention of the telegraph. An operator could send a message through a wire by varying the electric current. The movement of magnetized needles or of devices called electromagnets would show the variations in the current. Thus, an operator at the other end could receive and decode the message. In the decade following Oersted’s discovery, a number of primitive telegraphic devices were created by inventors in the United Kingdom and other countries.

The English inventor William Sturgeon developed an early electromagnet in 1825. A few years later, the American physicist Joseph Henry greatly improved on Sturgeon’s design. In 1830, Henry set up a crude telegraph using electromagnets that sent signals over more than 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) of wire. In 1837, he invented a device to boost the electrical signal along a wire when the signal became weak.

The most notable early device using electromagnets and needles was the one invented in England by William F. Cooke, an inventor, and Charles Wheatstone, a physicist. Cooke and Wheatstone created a telegraph that used five needles, each of which was connected to a separate wire, to transmit messages. Pulses of electric current caused two needles at a time to move and point to individual letters. Cook and Wheatstone patented their telegraph in England in 1837. They continued to develop their telegraph, eventually creating a version that used two wires and two needles. A later version used only one wire and one needle.

The Morse telegraph.

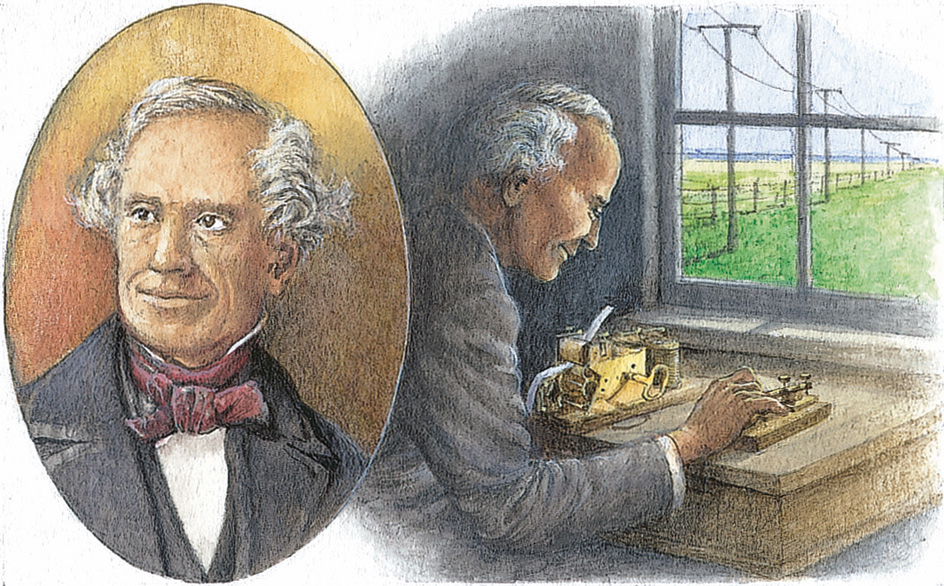

The American inventor and painter Samuel F. B. Morse is credited with making the first practical telegraph in 1837. He received a U.S. patent for his telegraph in 1840. However, Morse’s invention came after several decades of research by many people. He did not accomplish his feat alone.

Morse became interested in the telegraph in 1832. In November of that year he built his first model, which used a device called a portrule to turn the flow of electric current on and off at intervals. Morse also began work on a code for the telegraph, though not the code for which he is best known. His original code was based on the idea that a certain sequence of numbers would represent a word.

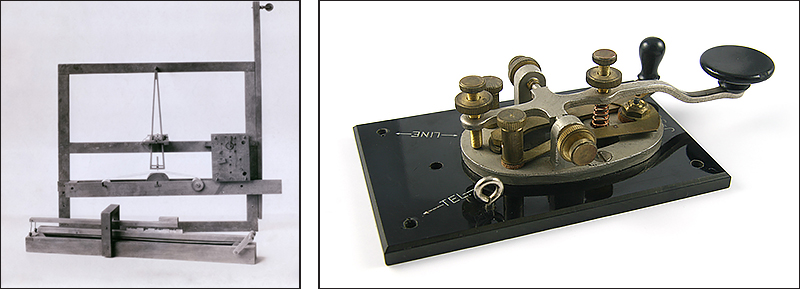

In 1835, Morse built a larger model that used an electromagnet to deflect a pencil suspended from a small picture frame. The pencil made short marks, called dots, or longer marks, called dashes, on a paper tape. The length of the marks was determined by the amount of electric current sent over a wire.

In 1836, Morse began to work with a chemistry professor named Leonard Gale. Gale helped Morse to improve the battery and the electromagnet in the telegraph so that electric current could be sent greater distances. Morse demonstrated this improved version of the telegraph on Sept. 2, 1837, sending a message over 1,700 feet (520 meters) of wire.

At that demonstration, Morse met machinist Alfred Vail, whose father agreed to help pay for further development of the telegraph. Later that year, Vail suggested that the dots and dashes represent letters rather than numbers. Vail assigned the simplest codes, such as one dot or one dash, to the most commonly used letters. Less frequently used letters have more complicated codes. For example, in Morse code the letter e is one dot, but the much more rarely used letter x is a dot, a dash, and two dots.

Vail also developed a sending and receiving device called a key. The key had a lever that the operator moved up and down to send signals. It also had a receiving device called a sounder. In the sounder, each burst of electric current caused an electromagnet to attract an iron bar called an armature. The armature struck the electromagnet and made a clicking noise that represented either a dot or a dash in Morse code. With each click, a pointed instrument attached to the armature marked the code on a strip of paper.

Construction and growth.

In 1843, the U.S. Congress approved $30,000 for Morse to build a telegraph line from the Capitol in Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. The first demonstration of the line occurred on May 1, 1844, when the Whig Party met in Baltimore to nominate candidates for president and vice president. Vail, who was waiting at the end of the telegraph line near Baltimore, found out from the passengers on a train traveling from Baltimore to Washington that the Whig Party had nominated Henry Clay for president and Theodore Frelinghuysen for vice president. He telegraphed the message to Morse in Washington. The train later arrived, and its passengers confirmed the news. On May 24, 1844, Morse sat at a sending device in the Supreme Court chamber of the Capitol and sent the first official telegraph message, “What hath God wrought!”

A year after the demonstration of the Washington-to-Baltimore telegraph line, Morse formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company. The company controlled his telegraph patents. Morse licensed the patents to others, setting off a great wave of telegraph line construction.

The telegraph quickly became an important means of transmitting news. Six New York City newspapers founded the Associated Press in 1848 to share the expense of gathering news by telegraph. In 1849, a German businessman named Paul Julius Reuter began a service that used homing pigeons to carry stock-market quotations between the terminal points of the telegraph lines in Belgium and Germany. In 1851, he founded the news service Reuters (now Thomson Reuters) in London to relay European financial news.

By 1851, the United States had more than 50 telegraph companies. Each one had short telegraph lines, and many lines were poorly built. As a result of faulty construction, lawsuits, and fierce competition, several companies went bankrupt. The public came to view the telegraph as unreliable. Delivery was unpredictable, many messages did not arrive, and rates were high.

Uses for the telegraph.

Despite poor service and high rates, many new uses for the telegraph developed during this period of early growth. For example, telegraph companies soon began to offer financial services. The first money order was sent on June 1, 1845.

Newspaper reporters used the telegraph to send stories to their newspapers. From the start of the construction of telegraph lines, telegraph companies advertised for business from newspapers. Many operators offered the newspapers special rates.

The telegraph became a vital tool during the American Civil War (1861-1865), not only for the press, but also for the armies on both sides. Telegraph operators felt so overworked during the war that they formed the National Telegraphic Union in 1863.

Brokers on Wall Street used the telegraph to gain quick access to important information, such as the current price of gold. In 1867, the New York Stock Exchange introduced stock tickers, telegraph devices that reported the purchase and sale of stocks.

Railroads used the telegraph to create a more efficient transportation network. In agreements between railroads and telegraph companies, railroads agreed to string telegraph lines along railroad rights of way. In return, telegraph companies agreed to transmit messages relating to railroad business free of charge and to give priority to messages concerning the movement of trains.

Western Union.

During the 1850’s, the U.S. telegraph industry worked to overcome the problems caused by the existence of more than 50 telegraph companies. The industry rebuilt short, disconnected, broken-down lines and combined them into extensive networks.

In 1851, Hiram Sibley and a group of businessmen from Rochester, New York, started the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company. They hoped to combine all the western telegraph lines into a single network. They bought and leased telegraph lines, railroad rights of way, and patent rights from other companies. In 1856, the company’s name became Western Union Telegraph Company. By 1866, Western Union had gained control of its major competitors and become the most successful of the telegraph companies.

Service expansion and improvement.

Telegraphy continued to spread around the world. In 1847, the German inventor Ernst Werner von Siemens helped found a company (now Siemens AG) that set up telegraph lines in Germany, Russia, and other nations. In 1850, the first underwater telegraph cable was laid between France and the United Kingdom. After several failed attempts, a permanent transatlantic link was achieved in 1866. The British scientist William Thompson, later Lord Kelvin, supervised the Atlantic cable project. See Cable (Telegraph cables) .

By the 1860’s, central telegraph offices existed in most major cities in the United States and Europe. Western Union completed the first transcontinental telegraph line in North America in 1861. In 1865, the International Telegraph Union, the forerunner of the International Telecommunication Union, was formed. This organization established standards for international telegraph communications. In 1869, a telegraph went into operation between Tokyo and Yokohama, Japan. By 1870, several lines connected India and the United Kingdom.

Western Union sent out weather reports from its major cities and began providing weather maps in 1868. The company established the first time service in 1877, relaying signals from the official government timekeeper, the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. Through these and other services, the telegraph connected communities and companies across North America and Europe. The government of the United Kingdom took over the British telegraph industry in 1870 and made it part of the British Post Office.

Improvements in telegraphy increased the message capacity of single wires and the speed of message handling and transmission. The duplex system, which could send two messages over one wire at the same time, one in each direction, had been developed in 1853 by the Austrian inventor Wilhelm Julius Gintl. But Gintl’s system failed to compensate for electrostatic interference in the wire, and so was impractical. The American inventor Joseph B. Stearns improved on this system. The system Stearns devised began operating in the United States in 1872. Two years later, American inventor Thomas A. Edison developed a quadruplex system, which handled four messages at the same time. In 1875, Emile Baudot, a French telegrapher, developed a multiplex system that could handle five at once.

Decline.

By the late 1800’s, the telegraph was a vital part of commerce, government, and the military. The introduction of the telephone in the 1870’s took away most of the short-distance communication business of the telegraph. By the late 1890’s, long-distance telephone communication threatened much of the remaining telegraph business. The telegraph continued to be used in the 1900’s, however, and the development of faster automated sending and receiving devices helped improve telegraph service. About 1900, the British inventor Donald Murray devised a telegraph system that used a keyboard to send text and a printer to receive it. He developed the system for the British Post Office. United States telegraph companies purchased Murray’s patent rights in 1912, and by the 1920’s, they had developed their own printing telegraph systems. The number of telegrams sent reached its peak in 1929, when over 200 million were transmitted.

In 1931, the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (now part of AT&T Inc.) introduced TWX, a telegraph service that sent messages directly from one unit equipped with a telephone line, printer, and typewriter to another. In 1958, Western Union introduced Telex, an advanced version of TWX, to the United States.

Telegraph service today

Despite the advances made in the 1900’s, the traditional telegraph could not compete with such communications equipment as computers and communications satellites. These machines, which operate much faster than the telegraph and can process many kinds of information, have almost completely replaced the telegraph.

Today, only a small number of companies in the world offer telegram service. People generally send telegrams only on special occasions. One company, Swiss-based Unitel Telegram Services, operates telegram businesses in a number of countries. In the United States, Western Union Financial Services, Inc., stopped offering telegram service in 2006.