Tire is a covering for the outer rim of a wheel. Most tires are made of rubber reinforced with some kind of fabric and are pneumatic (filled with compressed air). They are used on airplanes, automobiles, bicycles, buses, earth-moving and mining machinery, motorcycles, recreational vehicles, tractors, trucks, and many other kinds of vehicles. Some rubber tires, such as those used on many wagons and wheelbarrows, are solid rubber.

The main feature of rubber tires is their ability to absorb the shock and strain created by bumps in the road. Tires help provide a comfortable ride and help protect many kinds of cargoes. The air in a rubber tire supports the weight of a vehicle.

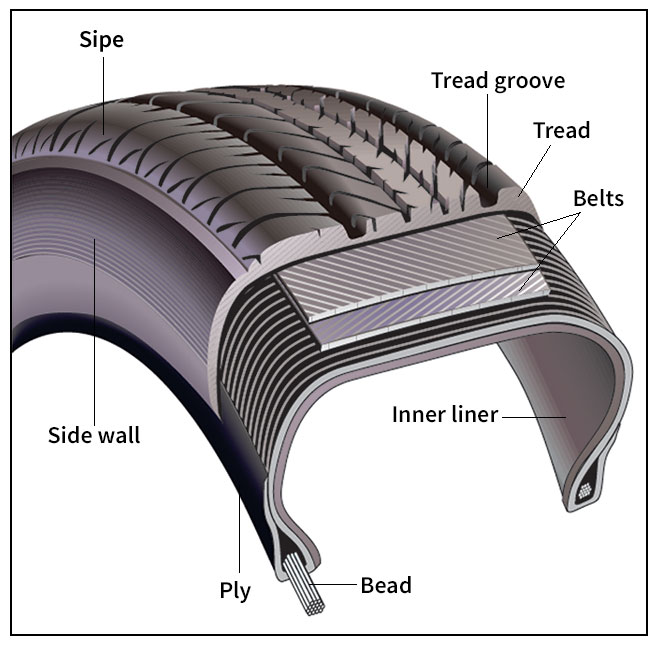

Another important feature of rubber tires is their ability to grip the road. The face of a tire, called the tread, has many deep grooves. These grooves and many smaller slits called sipes make up the tread pattern. The tread provides the traction that enables the tires to grip the road in wet weather. The tire body is composed of the rubber side walls (sides), which cover and protect the rest of the body and are made of high-strength bundles of wire for holding the tire on the wheel rim. The body also contains layers of rubberized cord fabric. Each layer is called a ply.

How tires are made

Preliminary operations.

Before a tire can be manufactured, several operations must be performed. They include mixing the rubber with sulfur and other chemicals, coating cord fabric with the rubber, and cutting the rubberized fabric into strips.

A machine called a Banbury machine mixes the rubber with the chemicals. The chemicals strengthen the rubber and increase its resistance to wear. The rubber comes from the machine in the form of sheets.

A calendering machine coats cord fabric with the rubber sheeting. Cord fabric is made of nylon, polyester, rayon, or steel. The triple rollers of the machine squeeze the cords and the rubber together, producing a rubberized fabric. A cutting machine then slices the rubberized cord fabric into strips of the necessary size.

Assembling a tire.

A tire is assembled mostly by hand, though some of the steps may be performed by specially designed machinery. The assembly process begins on a slowly rotating roller called a drum. The drum has the same diameter as the wheel on which the tire will be used. As the drum turns, a worker called a tire builder wraps an inner liner around the drum. The inner liner consists of a band of special rubber that makes the tire airtight. The tire builder then wraps the rubberized cord fabric around the drum, ply by ply. Most of today’s automobile tires have two belts of fabric between the plies and the tread. The belts are made of steel or manufactured fibers that resist stretching. Such fibers include aramid, fiberglass, and rayon.

After putting on the plies, the tire builder adds two beads. Each bead consists of several steel wire strands that have been wound together into a hoop and covered with hard rubber. A bead is put on each side of the tire. It is inserted at the point where the tire will come into contact with the rim of the wheel. The two ends of each ply are wrapped around the bead, securing the bead to the tire.

Next, the builder adds the rubber side walls, the belts, and the tread. The various parts of the tire are then pressed together by a set of rollers in a process called stitching.

The green (uncured) tire is now ready to be vulcanized. The vulcanization process combines chemicals with the raw rubber and makes a rubber product strong, hard, and elastic. The tire is taken off the drum and placed in a curing press. The press contains a large rubber bag called a bladder and a mold that has the sipes and large grooves of the desired tread pattern in it. The press operates like a giant waffle iron. It is closed, heat is applied, and the bladder is filled with steam. The filled bladder presses the tire against the mold. The bladder and the mold squeeze the tire into its final shape, complete with tread pattern. See Rubber (Vulcanization) .

Retreading tires.

After the original tread pattern has worn down, a tire–if it is in good condition–can be retreaded, or recapped. First, a machine rubs away the old tread. Then a worker applies new tread rubber and puts the tire into a mold. The new tread and tread pattern are then vulcanized to the old tire. Sometimes a new tread with a pattern that has already been vulcanized is cemented to the prepared tire body.

Types of tires and tread patterns

There are three basic kinds of automobile tires: (1) bias; (2) bias belted; and (3) radial, or radial ply.

Bias tires

are built with the fabric cord running diagonally–that is, on the bias–from one rim to the other. Each ply is added so that its cords run at an angle opposite to the angle of the cords below it.

As a vehicle moves, the plies of its tires rub against each other and against the tread in an action called flexing and squirming. This action produces inner heat, one of the major causes of tire wear. Extreme heat can separate the tread or split the plies.

Bias belted tires

are made in the same way as bias tires, but cord fabric belts are placed between the plies and the tread. The belts help prevent punctures and fight tread squirm.

Radial tires

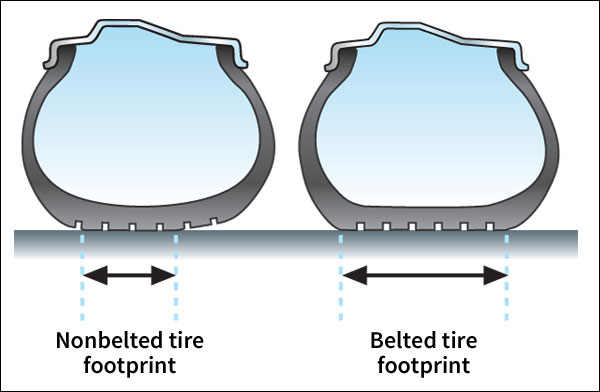

are built with the body fabric cord running straight across the tire from one rim to the other. All radial tires are belted. The combination of radial ply and belting produces a tire with longer tread life than either bias or bias belted tires. Radial tires give longer wear because they have less flex and squirm than bias ply tires. They also roll more easily and thus save fuel.

Low profile tires

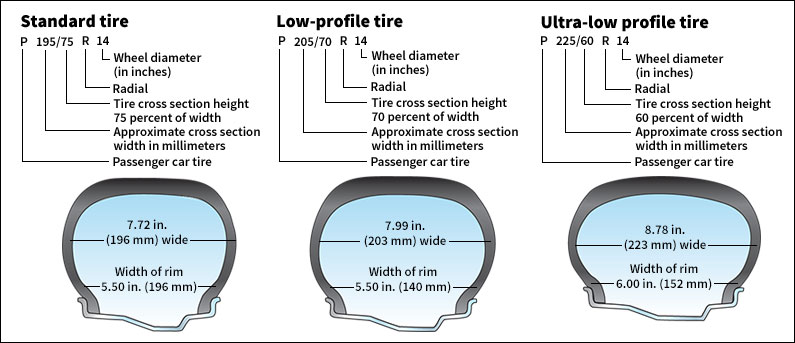

are used on many high-performance cars. These tires look pudgier than regular tires. They are wider (from side wall to side wall) than they are high (from tread to wheel rim). They put more tread into contact with the road than standard tires. This additional tread creates a wider footprint (track), which increases traction. The added stability provided by the tire shape gives a driver more control of a car at high speeds and around curves than standard tires give.

Tire tread patterns

are designed for a variety of special purposes. For example, snow tires have a tread with extra-deep grooves. This tread bites into snow and mud, providing exceptional traction. Tiny metal spikes called studs stick out of studded snow tires for added traction on ice. But studded tires have been banned in some areas because they can cause road damage. All-season, or all-weather, tires provide better traction than regular tires on snow- and rain-covered surfaces. Special tread patterns are made for the tires of racing cars, trucks, and various construction, farming, and military vehicles.

History

The pneumatic tire was invented in 1845 by Robert W. Thomson, a Scottish engineer. At that time, most vehicles had wooden wheels and steel tires. The steel tires preserved the wood and wore well. Thomson’s tires gave a smoother ride but were not strong enough. In 1870, the first solid rubber tires appeared in England. They were used on automobiles, bicycles, and buggies.

John B. Dunlop, a Scottish veterinarian, improved on Thomson’s invention in 1888. Dunlop developed air-filled rubber tubes for his son’s tricycle. These pneumatic tires provided a smoother ride and made pedaling easier than did solid rubber tires. Bike manufacturers in Europe and the United States soon began to use them.

Pneumatic tires appeared on automobiles in 1895. Like bicycle tires, they were single air-filled tubes. But as cars became heavier and were driven faster, the single tube tires could not hold enough air pressure for more than a short time. In the early 1900’s, two-part tires were developed. They consisted of a casing and a flexible rubber tube that fit inside the casing and held the air. This inner tube held from 55 to 75 pounds per square inch (3.9 to 5.3 kilograms per square centimeter) of air pressure. These tires were called high-pressure tires.

Then tire manufacturers learned that less air in the tires would not only support the weight of an automobile but also add comfort to the ride. In 1922, low-pressure tires, or balloon tires, were introduced. They held from 30 to 32 pounds per square inch (2.1 to 2.2 kilograms per square centimeter) of air pressure.

The tubeless tire was introduced in 1948. Its casing was made airtight by an inner liner. Since 1954, most new cars have come equipped with tubeless tires.

In 1966, the U.S. Congress passed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. The act called for minimum federal safety standards and a system of grading tires according to heat resistance, traction, and tread wear. These grades aid the consumer in choosing a tire. They are molded into the side wall along with the tire size, brand, maximum inflation pressure, maximum load, cord composition, and the symbol DOT, which shows that the tire meets safety standards.

In the 1970’s, manufacturers introduced thin, lightweight, “temporary use” spare tires. They also developed tires that would seal themselves if punctured. All-season tires appeared in the late 1980’s. In the 1990’s, manufacturers developed a tire that can be driven safely for some distance after being severely punctured. Specially strengthened sidewalls enable this tire to keep its shape even if all of the air escapes from it. Manufacturers also added sensors to some tires that indicate if the tires are properly inflated.

See also Dunlop, John B. ; Firestone, Harvey S. ; Goodyear, Charles ; Rubber .