Transplant, in medicine, is surgery that transfers any type of tissue or organ from one person to another. Transplanted tissues and organs replace diseased, damaged, or destroyed body parts. They can help restore the health of a person who might otherwise die or be seriously disabled. Transfers of such tissues as skin or hair from one part of a person’s own body to another part are also called transplants. This article focuses on person-to-person transplants.

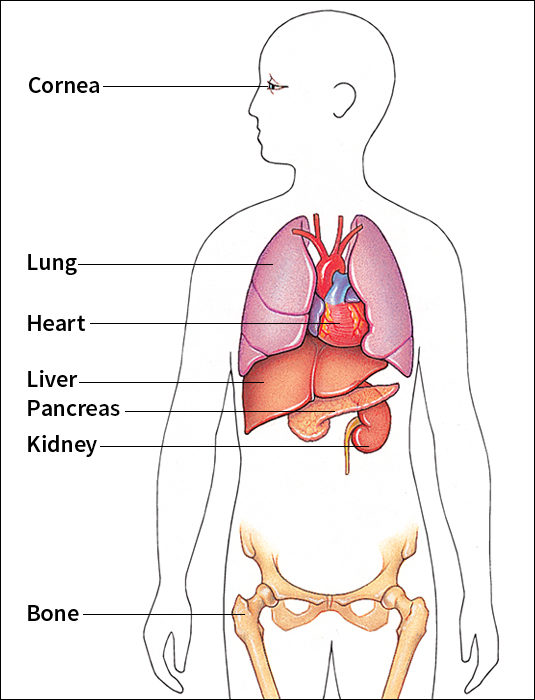

There are two major types of transplants—tissue transplants and organ transplants. A tissue is a group of similar cells that work together—bone and skin are examples. Organs are more complex than tissues. Each organ is made up of at least two kinds of tissue and performs a particular job for the body. For example, the heart—one of the most important organs—pumps blood. Some organs, such as the heart and lungs, cannot survive outside the body for more than a few hours. As a result, doctors must transplant these organs quickly.

Some tissues that are commonly transplanted—including bone, corneas, and skin—can be held for longer periods. Many tissues can be stored for future use in refrigerators or freezers at facilities called tissue banks.

Transplanted tissues and organs differ in that way that the body’s disease-fighting immune system responds to them. The immune system recognizes that many transplanted organs come from outside the body. It then attacks them as if they were disease-causing invaders. Doctors use special methods and drugs to protect new organs from attack. Most tissues do not require such protection because the immune system responds less strongly to them.

Tissue transplants

The most commonly transplanted tissues include corneas, skin, and bone marrow. The cornea is a piece of clear tissue that lies over the colored part of the eye and enables light to enter. Cornea transplants improve vision for patients whose corneas have been scarred by injury or clouded over by infection.

Skin transplants are used to temporarily cover areas of the body that have been badly burned and thus reduce the risk of infection. These transplants can last for several weeks until skin from another part of the patient’s body can be used for a permanent transplant.

Bone marrow transplants replace the blood-forming tissue inside bones. These procedures are used to treat certain kinds of cancer and serious blood disorders. See Bone marrow transplant. The hard outer tissue of bones can also be processed and transplanted to replace bones damaged by cancer or other diseases.

Organ transplants

In most developed countries, organ transplants have become an established form of treatment for a variety of diseases and injuries. Commonly transplanted organs include the heart, lungs, kidney, and liver. Most transplant operations last several hours, and most patients survive the operation. Patients usually remain in the hospital for 1 to 4 weeks, depending on the organ transplanted.

Qualifying for a transplant waiting list.

The first step in qualifying for a transplant is a thorough medical evaluation. In most hospitals that perform transplants, these evaluations are done by a team of doctors and nurses with broad experience in transplant medicine. Patients must have badly damaged organs that do not respond to other forms of treatment. The damage must be severe enough to greatly reduce quality of life or significantly shorten life expectancy.

Most transplant teams also include social workers, psychologists, or members of the clergy. These participants help determine that patients can tolerate the emotional and psychological demands of transplant surgery.

After patients are accepted as transplant candidates, they must wait until suitable donor organs can be found. In the United States, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), in Richmond, Virginia, maintains lists of all U.S. patients who are waiting for an organ transplant.

Sources of donor organs.

Other people are the main source of donor organs. Living people can donate organs that they can survive without. For example, a person can donate one kidney and remain healthy. Sometimes people can donate part of an organ without suffering harm. If someone donates part of the liver, the organ will regrow the donated part. But most donor organs come from cadavers—bodies of people who have died.

Cadaver organs

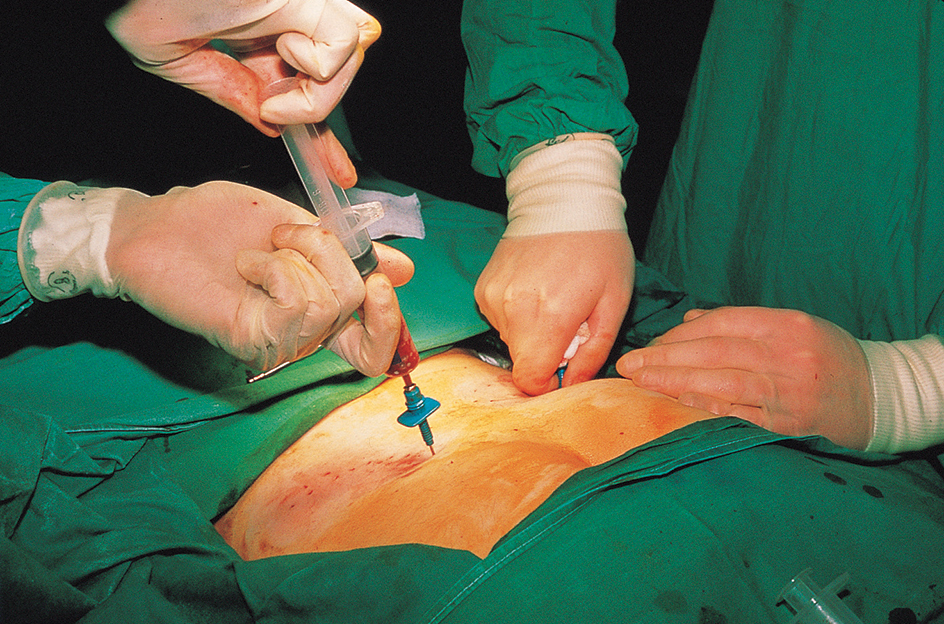

are usually taken from someone who accidentally received a fatal head injury. After such an accident, the brain dies, but the rest of the body is kept alive with a respirator or other artificial means. Once all brain activity stops, hospital staff or a representative of a local Organ Procurement Organization (OPO) may ask the family about organ donation. If the family agrees, the OPO begins a search for suitable recipients. After a recipient has been chosen, organs are removed from the donor and taken to recipients’ hospitals. Meanwhile, the recipient is prepared for surgery.

Many patients die while awaiting organ transplants because the number of donors falls far short of the number needed. To save lives, health care professionals encourage more people to consider organ donation. Attitudes about organ donation vary among individuals in different nations. The United States and the United Kingdom, for example, rely on a policy called informed consent. In this approach, patients or their closest relatives must directly give permission for organs to be used for transplants. People can express their desire to donate organs at the time of their death by carrying a signed donor card or by marking a space provided on their driver’s license.

Other countries—including Austria and Belgium—approach organ transplantation with a policy of presumed consent. In this approach, medical professionals assume that organs can be used for transplantation after death.

Nonhuman sources of organs.

Because of the shortage of human organs, researchers are actively investigating the possibility of obtaining donor organs from animals. Transplanting organs from one species to another is called xenotransplantation << ZEHN uh TRANS plan TAY shuhn >>. Use of pigs as organ donors is an especially active area of research. Pigs are already widely raised for food and leather, and their organs are about the same size as adult human organs.

One challenge of xenotransplantation is preventing the recipient’s immune system from destroying a donor organ from another species. The human immune system reacts especially vigorously to nonhuman organs. This reaction is called rejection.

The first successful xenotransplants of whole organs were performed in the early 2020’s. In many countries, governments are developing strict regulations to ensure the safety of xenotransplantation.

Preventing rejection.

Rejection occurs when the body’s immune system attacks a transplanted organ. The immune system fights disease by finding and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other foreign materials in the body. If the immune system recognizes that a transplanted organ came from outside the body, the system attacks the organ as a dangerous invader. Doctors try to prevent rejection by choosing the best donor and prescribing special medication to protect the transplant.

Matching donors and recipients.

To reduce the risk of rejection, doctors must find a donor who has the same blood type as the patient. For some organs—such as the lung, heart, and liver—it is also important that the donor’s organ be relatively similar in size to the one it replaces.

In addition to matching blood type, physicians also try to match certain inherited proteins of the donor and the patient. These proteins, called HLA antigens, occur on the surface of cells. Each person has a unique combination of HLA antigens, which are determined by genes (hereditary instructions in cells). A transplant is more likely to succeed if the donor’s and recipient’s HLA antigens match. Doctors try to match six different HLA antigens from the donor and recipient. HLA matching is used mainly in kidney and bone marrow transplantation.

The best possible organ donor would be a patient’s identical twin. Because identical twins have all the same genes, all antigens would match perfectly and the patient’s immune system would not react to the transplant. As a result, rejection would not occur. Other relatives of the patient are the next best organ donors because they are next most likely to have similar HLA antigens.

Using immunosuppressive drugs.

Because transplants usually come from unrelated individuals, most patients must take immunosuppressive << ih `myoo` noh suh PREHS ihv >> drugs. These drugs prevent rejection by reducing the activity of the immune system. Unfortunately, the reduced immune activity also hampers the body from defending itself against infections. As a result, patients who take immunosuppressive drugs have an increased risk of infection.

Immunosuppressive drugs commonly used to prevent rejection include azathioprine << `az` uh THY uh preen >>, cyclosporine << `sy` kloh SPAWR een >>, and prednisone << PREHD nuh sohn >>. These drugs interfere with the action of cells of the immune system that are directly responsible for the rejection of the organ. Cyclosporine is especially useful because it interferes less than other immunosuppressive drugs with the immune system’s ability to fight infection. Most transplant patients require a combination of cyclosporine and other immunosuppressives.

Survival rates.

Kidney transplants are the most successful type of organ transplant. Ninety percent or more of these transplants are still functioning after one year. About 80 percent of heart transplant patients and about 75 percent of liver transplant patients survive for at least one year, and about 70 percent of these patients live for three years or longer. But survival requires continued medical care, including close supervision, and patients must take immunosuppressive drugs for the rest of their lives.