Trudeau, << troo DOH, >> Pierre Elliott (1919-2000), served as prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and from 1980 to 1984. He was the third French-Canadian prime minister. Like the first two—Sir Wilfrid Laurier and Louis S. St. Laurent—he was a Liberal.

The energetic and wealthy Trudeau generated great interest among Canadians, particularly the nation’s youth. But during the late 1970’s, his popularity and that of his party declined as Canada’s economic problems worsened. The Progressive Conservatives defeated the Liberals in May 1979, and the Conservative leader, Joe Clark, succeeded Trudeau as prime minister. However, Clark’s government fell from power at the end of the year, and Trudeau led the Liberals to an easy victory in February 1980.

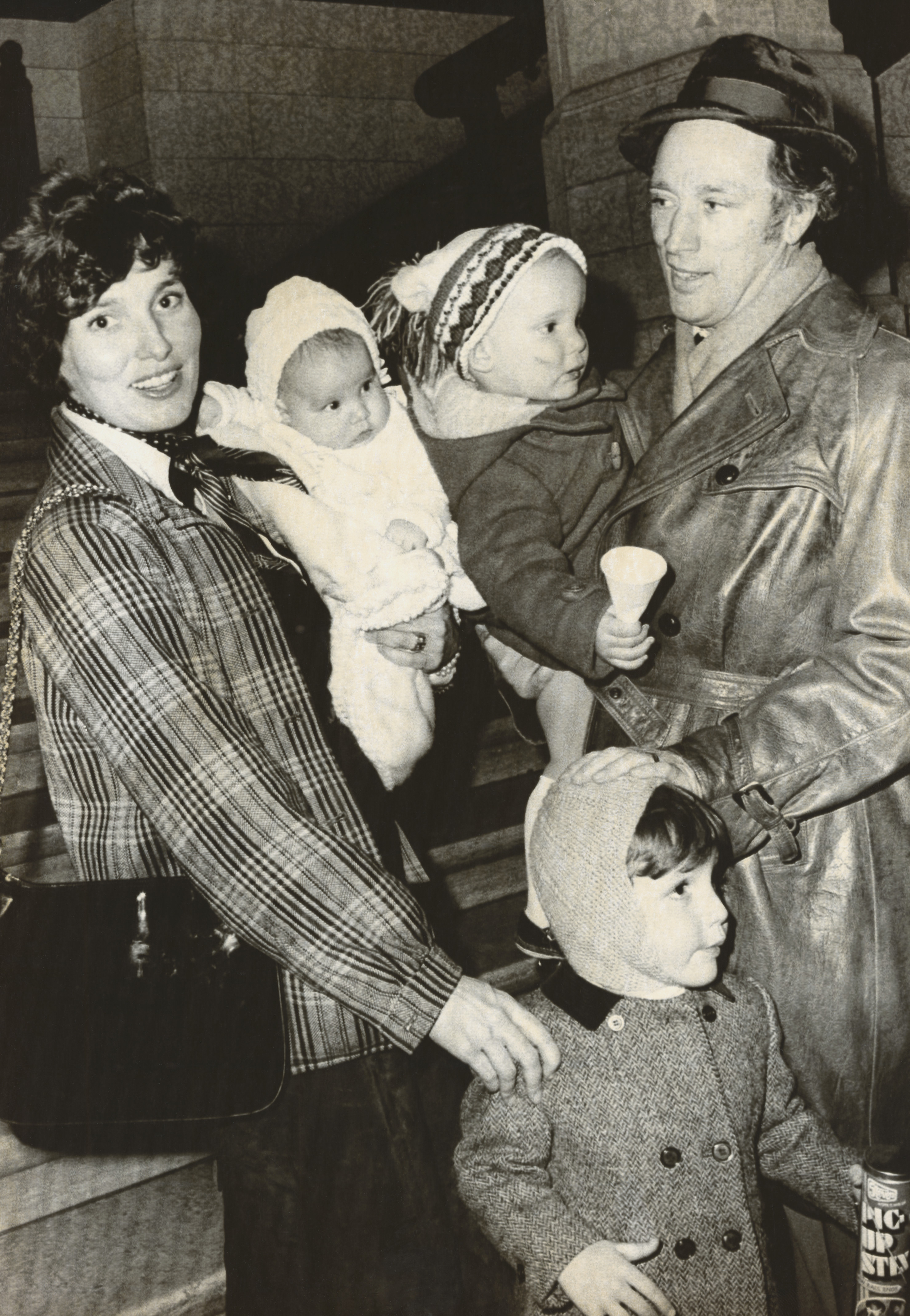

Before his first term as prime minister, Trudeau had worked as a lawyer and law professor and had only three years of experience in public office. Trudeau’s social life had made him famous. He often wore colorful clothes; drove fast cars; and enjoyed skiing, skin diving, and canoeing. Even as prime minister, his personal life generated interest. In 1971, he surprised the nation by marrying Margaret Sinclair, the daughter of a former member of Parliament. Their romance had received no publicity. The Trudeaus had three children, Justin (1971-…), Alexandre (1973-…), and Michel (1975-1998). In 1977, Trudeau and his wife separated. Trudeau received custody of the children. The couple divorced in 1984.

As prime minister, Trudeau worked to broaden Canada’s contacts with other nations and to ease the long-strained relations between English- and French-speaking Canadians. He achieved a personal goal in 1970, when Canada and China agreed to reestablish diplomatic relations. At home, Trudeau faced such problems as rapid inflation, high unemployment, and a movement to make the province of Quebec a separate nation. Trudeau achieved another major goal in 1982, when the Canadian constitution came under complete Canadian control. Previously, constitutional amendments required the British Parliament’s approval.

Early life

Boyhood.

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau was born in Montreal on Oct. 18, 1919. His father’s family had gone to Canada from France in the 1600’s. His mother’s family was descended from British colonists who moved to Canada because of their loyalty to the United Kingdom during the Revolutionary War in America (1775-1783). Trudeau, his sister Suzette, and his brother Charles spoke French and English with equal ease. Trudeau’s father became wealthy as owner of a chain of service stations.

Education.

Trudeau grew up in Montreal, where he attended a Jesuit college, Jean-de-Brébeuf. He received a law degree from the Université de Montréal (University of Montreal) in 1943. While at the Université de Montréal, he enlisted in the Canadian Officer Training Corps. He later completed his training with an army reserve unit.

In 1945, Trudeau earned a master’s degree in political economy at Harvard University. He then studied at the École des Sciences Politiques (School of Political Sciences) in Paris and at the London School of Economics and Political Science in the United Kingdom.

His travels.

In 1948, Trudeau set out to tour Europe and Asia. He traveled by motorbike or hitchhiked with a knapsack on his back. First he visited Germany, Austria, and Hungary. Then he traveled through Eastern Europe. In Jerusalem, the Arabs arrested him as an Israeli spy. But he continued on to Pakistan, Afghanistan, India, Burma (now Myanmar), Thailand, Indochina, and China. He returned to Canada from China in 1949.

Next, Trudeau worked in the Privy Council office in Ottawa as a junior law clerk. He returned to Montreal in 1951 and began to practice law. In 1960, Trudeau and five other Canadians toured China. They were among the first Western tourists admitted since the Communists conquered China in 1949. Trudeau became a law professor at the Université de Montréal in 1961.

Entry into public life

During the late 1940’s and the 1950’s, Trudeau became concerned about the political situation in Quebec. The province was governed by Premier Maurice Duplessis and the Union Nationale Party. Trudeau and a group of youthful liberal friends set out to expose what they saw as dishonesty in the provincial government. They believed this corruption had resulted from political, religious, and business leaders working together to prevent reforms. To express their ideas, they established the magazine Cité Libre (Community of the Free).

Trudeau worked in many ways for reform in Quebec. The most publicized event took place in 1949 when miners went on strike in the town of Asbestos. Premier Duplessis ordered the provincial police to aid the company and the nonunion men it tried to hire during the strike. The strikers blockaded the roads into Asbestos and kept the strikebreakers from entering. Trudeau spent more than three weeks rallying the strikers. The police and many ministers called him an “outside agitator.”

In 1956, Trudeau helped organize Le Rassemblement (The Gathering Together). The group’s 600 members worked to explain democracy to the people of Quebec and to persuade them to use it. Trudeau later served as president of the group. In 1960, the Union Nationale Party was voted out of office.

French Canadians demanded more than democratic reform for Quebec. They had always struggled against what they believed was discrimination by Canada’s English-speaking majority. Many French Canadians told of being refused jobs in government and industry because they spoke French. They feared that the French language would disappear in Canada if they were required to use English. They also feared that with the loss of their language they would lose their national identity and their culture and customs. Some demanded full equality. Others called for Quebec to become a separate country. During the 1960’s, demands for separation from Canada became even stronger.

Trudeau favored preserving the French culture in Canada. But he opposed the creation of any country in which nationality was the only major common bond.

Member of Parliament.

In 1965, Trudeau decided to enter national politics and run for a seat in the House of Commons as a member of the Liberal Party. In November 1965, he was elected to Parliament from Mont-Royal, a Montreal suburb.

Parliamentary secretary.

In January 1966, Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson appointed Trudeau as his parliamentary secretary. Trudeau used this position to influence the government’s policy on constitutional issues. He wanted the constitution changed to provide a stronger federal government and to promote more cooperation among the provinces. For example, Trudeau believed the wealthy provinces should help support the poorer ones. He favored a tax program that would divide tax money more fairly among the provinces. In March 1966, the government adopted this kind of plan.

Minister of justice.

In April 1967, Pearson named Trudeau to the Cabinet as minister of justice and attorney general. In this post, Trudeau introduced legislation to strengthen gun-control laws and to reduce restrictions on abortion, divorce, gambling, and same-sex relationships. He believed that individuals should be free to do whatever they wished if they did not endanger society as a whole. The government sponsored similar legislation after Trudeau became prime minister.

Prime minister

In December 1967, Pearson announced his intention to retire. Trudeau was elected leader of the Liberal Party on April 6, 1968, and he became prime minister on April 20. He called a general election for June 25, and the Canadian voters strongly supported him in that election.

Foreign affairs.

Trudeau wanted to strengthen Canada’s independence in world affairs. Early in his term, he changed the nation’s defense arrangements and expanded its relations with China and the Soviet Union.

New defense policy.

Trudeau adopted a defense policy that emphasized the protection of Canadian territory. In 1970, he withdrew about half of the 9,800 Canadian troops serving with forces of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe.

Foreign relations.

In 1970, Canada and China agreed to reestablish diplomatic relations. These ties had ended when the Communists gained control of China in 1949. The agreement had been one of Trudeau’s chief goals. Trudeau visited China in 1973. He traveled to the Soviet Union in May 1971, and Premier Aleksei N. Kosygin of the Soviet Union toured Canada five months later. Trade increased with both China and the Soviet Union.

The national scene.

Trudeau worked hard to help preserve the French heritage in Canada. For example, he greatly expanded the use of the French language in government services. Trudeau hoped his efforts would strengthen national unity. But relations between English- and French-speaking Canadians remained tense.

Domestic legislation.

Parliament passed several far-reaching bills that were supported by Trudeau. In 1969, Parliament approved the Official Languages Act. This law requires courts and other government agencies to provide service in French in districts where at least 10 percent of the people speak French. It also requires service in English in districts where at least 10 percent of the people speak that language. The Election Act, passed in 1970, reduced the minimum voting age in national elections from 21 to 18. In 1971, Parliament extended unemployment insurance benefits to cover nearly all Canadian workers. In 1976, Parliament abolished the death penalty.

The October Crisis.

Terrorism by Quebec separatists in October 1970 forced Trudeau to make his most difficult decision as prime minister. Members of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), an underground separatist group, kidnapped Pierre Laporte, the labor minister of Quebec, and James R. Cross, the British trade commissioner in Montreal. Trudeau suspended civil liberties and sent thousands of federal troops to Quebec. He invoked the War Measures Act, which permits police to search and arrest without warrants and to deny bail.

Laporte was murdered, and four men were later imprisoned for the crime. The government let Cross’s kidnappers go to Cuba in return for his release. Trudeau’s firm stand received strong popular support.

The economy.

Inflation became one of Canada’s chief problems in 1969. To halt rising prices, Trudeau reduced government spending and eliminated thousands of civil service jobs. These policies contributed to a sharp increase in unemployment in 1970.

Economic conditions in Canada worsened in August 1971, when the United States placed a 10 per cent surcharge (extra tax) on many imports. The surcharge affected about a fourth of Canada’s exports. In September, unemployment reached 7.1 per cent, the highest level since 1961. To encourage spending and help create jobs, Trudeau ordered cuts in individual and corporation income taxes. He also made available several hundred million dollars in loans for construction projects. The U.S. surcharge was ended in December.

The 1972 election.

Trudeau called a general election for Oct. 30, 1972. He promised to seek new ways to reduce unemployment if he were returned to office. In the election, the Liberal and Conservative parties each won about 110 seats in the House of Commons. The Liberals failed to win a parliamentary majority, but Trudeau remained prime minister. Canada’s economy expanded in 1973. But rapidly rising prices for clothing, food, fuel, and shelter caused hardship for many Canadians.

The 1974 election.

On May 8, 1974, the House of Commons passed a motion expressing no-confidence in Trudeau’s government. This motion, which forced a new general election, came on a vote concerning Trudeau’s proposed budget. It was the first time that a Canadian government was defeated over its budget.

In the election of July 1974, Trudeau led the Liberal Party to victory. This time, the party gained a majority in the House of Commons, winning 141 of the 264 seats.

New economic policies.

Trudeau’s government also was concerned about the influence of foreign companies on the Canadian economy. In the mid-1970’s, for example, U.S. firms controlled over half of Canada’s manufacturing. Trudeau supported establishment of a Federal Investment Review Agency to ensure that foreign investments in Canada serve Canada’s best interests. This agency, which was approved by Parliament in 1973, began to operate in 1974.

Inflation continued to soar in 1975. Late that year, the Trudeau administration set limits on price and wage increases. The controls expired in 1978.

The separatist challenge

to Canada’s national unity became more serious in 1976. The Parti Québécois, a political party that favored the separation of Quebec from Canada, won control of the province’s government. Trudeau spoke out strongly against separatism.

The 1979 election.

In March 1979, Trudeau called a general election for May 22. During the campaign, the Progressive Conservatives criticized Trudeau and the Liberals for their failure to solve Canada’s economic problems. In the election, the Progressive Conservatives won 135 seats in the House of Commons, the Liberals won 115, and 32 seats went to smaller parties. Joe Clark, leader of the Conservatives, replaced Trudeau as prime minister. On November 21, Trudeau announced his intention to resign as party leader.

Return to power.

The Liberals planned to select Trudeau’s successor in a party convention in March 1980. But on Dec. 13, 1979, the House of Commons passed a motion of no confidence in Clark’s government. The vote came during consideration of the government’s proposed budget, which called for tax increases.

As a result of his government’s defeat, Clark called a general election for Feb. 18, 1980. Trudeau led the Liberals in the campaign. He climaxed an amazing political comeback when the Liberals won a majority of the seats in the House of Commons. Trudeau became prime minister again on March 3.

Trudeau’s new administration soon faced a serious challenge. The government of Quebec asked Quebecers to vote on whether the provincial government should have authority to negotiate for sovereignty association with Canada. Sovereignty association would have given Quebec political independence but maintained its economic ties to Canada. Trudeau campaigned against giving Quebec’s government such authority, and the voters of Quebec rejected the proposal on May 20, 1980.

Trudeau achieved a major goal in 1982 when the British Parliament approved an act giving Canada complete control over the Canadian constitution. The act, called the Constitution Act of 1982, set up a procedure for approving constitutional amendments in Canada instead of in the United Kingdom. Previously, many amendments required the British Parliament’s approval.

A recession struck Canada during the early 1980’s. The economy began to recover in 1983. But unemployment remained high, and public support for Trudeau’s economic policies steadily declined. On June 30, 1984, Trudeau resigned as prime minister. He had held office for 15 years, longer than almost any other prime minister. W. L. Mackenzie King served for 21 years and Sir John Macdonald for almost 19 years. Trudeau was succeeded by his former finance minister, John N. Turner.

Later years

After he resigned as prime minister, Trudeau continued to play an important role in Canadian politics. He was especially influential as an opponent of Quebec nationalism and of proposals for shifting power from the federal government to the provinces. In the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, he helped generate opposition to two government plans that were designed to satisfy the demands of Quebec nationalists. These plans, the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown accord, called for revising the Canadian constitution to recognize Quebec as a distinct society within Canada. They also called for increasing the powers of Quebec and the other provinces. The plans were proposed by the government of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. Mulroney, leader of the Progressive Conservatives, had replaced Turner as prime minister in 1984.

Trudeau helped lead opposition to the Meech Lake Accord through well-timed speeches and through testimony before Canada’s Parliament. The agreement failed in 1990 when the legislatures of Manitoba and Newfoundland refused to approve it. Trudeau expressed his opposition to the Charlottetown accord in a number of influential speeches and writings. The accord was defeated by a majority of Canadian voters in a referendum in 1992.

Trudeau died on Sept. 28, 2000, and received a state funeral. He was buried next to his parents and grandparents in the St.-Rémi-de-Napierville Cemetery in St.-Rémi, Quebec. In 2015, Trudeau’s son Justin became prime minister of Canada.