Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.), also called the Soviet Union, was the world’s first and most powerful communist country. It encompassed all of Russia, along with the territories of 14 other present-day countries. It was the largest country in the world in area, covering more than half of Europe and nearly two-fifths of Asia. The Soviet Union had the third largest population in the world, after China and India. The U.S.S.R. existed from 1922 to 1991. In 1991, the Communist Party lost power, and the Soviet Union broke up into a number of independent states.

The Soviet Union was formed as a result of the Russian Revolution of 1917, which brought the Communist Party to power. The U.S.S.R was officially created in 1922 when Communist Russia joined with three other territories under the name Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. These became the first of the country’s 15 union republics. The other republics were created and added from 1922 to 1940. The 15 union republics were Armenia, Azerbaijan, Byelorussia (now Belarus), Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan (also spelled Kazakstan), Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldavia (now Moldova), Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Each republic had its own government, but these governments were strictly under the control of the Communist central government in Moscow.

Soviet leaders sought to entirely transform the U.S.S.R. After seizing control of the country in 1917, they undertook enormous economic, cultural, and social changes. The agrarian (agricultural) society became more urban and well educated, and achieved many advances in the arts and sciences. At its height, the Soviet Union was an industrial giant, ranking second after the United States in total production. For years, it led all other countries in space exploration. It had the largest armed forces in the world and an immense nuclear arsenal.

However, many Soviet families lived in crowded conditions because there was not enough housing. There were often shortages of meat, shoes, and many other basic goods. The Communist Party controlled the Soviet Union’s government, economy, educational system, and media. It restricted individual freedoms and punished those who opposed state policies. Under the dictator Joseph Stalin, state policies resulted in millions of deaths. Although the country experienced rapid industrial growth, its economic system was inefficient, corrupt, and often failed to meet the people’s needs.

When the Communist Party lost control in 1991, the Soviet republics—excluding Georgia and the three Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—formed a loose confederation called the Commonwealth of Independent States. The Soviet Union ceased to exist.

Government

The Soviet Party-State.

The government of the Soviet Union was organized into two institutions: the Communist Party and a state administration. Throughout nearly all of Soviet history, the party was superior. Powerful party leaders controlled both the party and the state.

The Communist Party.

Russia’s Communist Party formed in 1903 as a secret organization dedicated to leading a global communist revolution. Soon after seizing power in Russia in 1917, the Communists banned all other political parties, which remained outlawed until 1990.

By the 1920’s, the Communist Party structure was like a pyramid. At the bottom of the pyramid were thousands of primary party organizations, or cells. These groups were established in such places as factories, farms, government offices, and schools. They were responsible for local political and economic life. Any Soviet citizen over the age of 18 could apply to join the Communist Party at the primary party level. At the time of the country’s breakup, about 16 million people—about 6 percent of the Soviet population—were Communist Party members.

Just above the primary party organizations were the district party organizations. The district organizations operated under the regional party organizations, which, in turn, reported to the republic party organizations.

At the top of the Communist Party pyramid were the party congresses, which met periodically—usually every five years. Thousands of delegates from party organizations throughout the country attended these congresses. Each congress elected a Central Committee to handle its work. The Central Committee, in turn, elected a Politburo (Political Bureau) and a Secretariat. The Politburo was the most powerful body in the Soviet Union.

In practice, party leaders in the Politburo and Secretariat selected supporters to sit on the Central Committee. Beginning with Joseph Stalin, the general secretary, or chairman, of the Central Committee headed the Politburo and the Secretariat and was the most powerful person in the U.S.S.R.

The Soviet State

was a massive and complex bureaucracy. The main body of the official Soviet central government was a two-house federal parliament called the Supreme Soviet of the U.S.S.R. Soviet is a Russian word meaning council. The two houses were the Soviet of the Union and the Soviet of Nationalities. The members of each house were called deputies. The number of deputies to the Soviet of the Union from each republic depended on population. Each republic—and certain other political units within the Soviet Union—sent a fixed number of deputies to the Soviet of Nationalities. For most of the country’s history, the Supreme Soviet met only twice a year. Almost all the deputies were party members, and the Soviet passed without question all laws proposed by the Communist Party’s leaders.

The Supreme Soviet selected an executive body, the Presidium. The Chairman of the Presidium was the Soviet Union’s legislative leader, head of state, and commander of the armed forces, though the Politburo held the real power.

The Soviet government also included the Council of Ministers, which dealt with particular areas of control, such as defense and education. Until 1946, the ministers were called commissars, and they formed a Council of People’s Commissars, or Sovnarkom. Although officially elected by the Supreme Soviet, the Council was in fact chosen by Communist Party leaders. The head of the Council was known as the Premier of the Soviet Union (the Chairman of the Sovnarkom).

The Committee on State Security, known from 1956 to 1991 as the KGB, was an agency of the Council of Ministers. It was the government’s political police system and had offices and agents throughout the Soviet Union.

Union republics and local and regional government.

The Soviet Union was internally divided into union republics, each with its own party organization and state officials. Below the republic level, territories were divided into regions and districts.

In addition to the union republics, the Soviet Union included various autonomous republics, autonomous regions, and autonomous districts. Autonomous means self-governing, but the autonomous republics, regions, and areas actually had little control over their own affairs. The political structure of the union republics and the autonomous republics was much like that of the entire country. Each republic was governed by a supreme soviet with a presidium, and a council of ministers. Each one also had its own constitution. The lower levels of local government, from autonomous regions to small districts, had soviets of people’s deputies.

Armed forces

of the U.S.S.R. were the largest in the world. At the time of its breakup, the Soviet Union had a total of about 4 million people in its army, navy, and air force.

People

The population of the Soviet Union consisted of more than 100 ethnic groups. The Soviet republics were set up on the basis of ethnic groups and carried their names. For example, Georgians lived mainly in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (now the independent nation of Georgia), and Armenians were centered in the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (now independent Armenia).

Slavic ethnic groups made up about 70 percent of the total Soviet population. The Russians, the largest Slavic group, made up about half of the population. They lived throughout the country, including in the non-Russian republics. The Ukrainians were the second largest Slavic group, and the Belarusians were the third largest. In 1991, the Ukrainians and Belarusians formed their own independent nations.

Turkic peoples ranked second in number to Slavic peoples in the U.S.S.R. The largest Turkic groups included the Uzbeks, the Kazakhs, the Kyrgyz people, and the Turkmen. Other ethnic groups included the Tajiks, Moldovans, Chechens, Georgians, and Germans.

Many other ethnic groups, some related to Native Americans of the Far North, lived in Siberia. They spoke a variety of languages.

To win support from different ethnic groups, Soviet leaders at first supported non-Russian languages, cultures, and education. Beginning in the 1930’s, however, the party began to advocate Russia’s role as the U.S.S.R.’s leading nation. The government continued to recognize many non-Russian ethnic groups, but Russian language and culture became dominant. Languages once written in the Roman or Arabic alphabets had to be written in the Cyrillic alphabet of the Russian language. Many people who supported the single-culture idea were given top political and economic positions. Their privileged status caused friction with minority ethnic groups. Under Stalin, ethnic groups suspected of disloyalty were forcibly removed from their homelands.

Jews, who were listed as a nationality group by the Soviet census, faced widespread discrimination in the U.S.S.R. Jews had faced severe persecution in the late Russian Empire. After the Revolution, many Jews played important roles in the Communist Party, the government, and in academic institutions. However, Jewish religious practices were restricted, and even nonreligious Jews faced widespread prejudice (opinion without fair judgment) throughout the Soviet era.

Way of life

Personal freedom.

For much of Soviet history, the people had little personal freedom. During the reign of Stalin, in particular, many lived in fear. The secret police arrested millions of citizens suspected of anti-Communist views or activities. The victims were shot or sent to prison camps. In the late 1980’s, the government began to grant the people greater freedom. It allowed criticism of the Soviet system. Also, the works of writers whose views had been officially condemned were permitted to be read openly.

Until 1990, the Soviet government restricted religious practices. The Communist Party was officially atheist (the belief that there is no God). Party officials believed that religion existed only to comfort poor people who were economically exploited (taken advantage of). In their view, religion had no place in a communist country. They discouraged and sometimes punished religious observance. Religious worship of all kinds survived throughout the Soviet period, however, and the restrictions gradually decreased. In 1990, the government promised freedom of religion.

Privileged classes.

The Communist Party hoped to achieve a classless society—a society with neither rich nor poor people. They believed that in capitalist countries, the rich use their control of the means of production—such as factories, farms, and banks—to exploit the poor. The Communists thought that if all the people controlled the means of production together, no one would be exploited. To achieve this vision, they took control of factories, banks, railroads, and other economic sectors. To see to people’s needs, they provided social welfare benefits, such as universal education, housing, and free medical and hospital care.

The Communists failed to achieve a classless society. The nobility and wealthy classes of the pre-revolutionary era disappeared. However, new groups with special rights developed under the Soviet system. These groups included top officials of the Communist Party and the government, and some professional people, including certain favored artists, engineers, scientists, and sports figures. They enjoyed many luxuries most Soviet citizens did not have, including better food, cars, and comfortable apartments. Privileged Soviet citizens also had access to higher quality education and other government services.

City life.

By 1990, about two-thirds of the Soviet people lived in urban areas. Cities were crowded, and most families lived in small and poorly maintained but cheap apartments. Housing shortages forced some families to share space and kitchen or bathroom facilities with other families.

Because of poor economic planning and problems with distribution, there were frequent shortages of basic goods. Shoppers often had to spend much time searching for things they needed and waiting in line. Quality or imported goods were scarce and often only available to privileged groups, such as high party officials.

Rural life.

Living conditions in the rural areas of the Soviet Union were worse than in the cities. In rural villages, many people lived in small log huts or in community apartments. Many families had no gas or indoor plumbing, and some did not have electricity.

Most people in rural areas worked on huge government-controlled farms, called sovkhozy, or on collective farms, called kolkhozy. Farmers were allowed to cultivate small plots of land for private use and to keep a few animals, selling any surplus produce. These private plots generated about one-fourth of the total value of agricultural production in the U.S.S.R.

Education.

During the early 1900’s, most of Russia’s people were peasants with low levels of education. After the Communists seized control, they strongly promoted education and literacy. Highly trained managers and workers were needed to build the country. To meet this need, the government expanded its schools and made major improvements in education. The schools stressed science and technology. Soviet achievements in these fields were among the highest in the world.

Beginning in 1958, Soviet children had to attend school for 11 years, from the age of 6 to 17. Soviet schools followed a standardized program that required students to study many subjects. In addition to schoolwork, students were graded on classroom behavior and leadership in group activities.

The Soviet Union had many schools for gifted children, who were chosen by examination. These schools provided extra instruction in the arts, languages, or mathematics and science.

After ninth grade, many students attended technical or trade schools. The Soviet Union also had about 70 universities and more than 800 technical institutes and other schools of higher education. For the most part, both basic schooling and higher education were free.

Science and technology.

The Soviet government established many research institutions and employed hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers, and technicians. These specialists made it possible for the Soviet Union to become an industrial and military power. Soviet scientists developed new processes and new technology for industries, and new weapons for defense. In addition, their work enabled the U.S.S.R. to lead the world in space exploration. In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. In 1961, Soviet air force officer Yuri A. Gagarin orbited Earth and became the first person to travel in space.

The arts.

For most of the history of the Soviet Union, the Communist Party restricted artistic expression. After a brief period of artistic freedom and experimentation in the 1920’s, the government permitted only an art style called socialist realism, which emphasized the goals and benefits of Soviet socialism. Such writers as Boris Pasternak and Alexander Solzhenitsyn were disciplined for criticizing Communism. Their works, along with those of many others, were prohibited in the Soviet Union for years. In the late 1980’s, however, the Soviet government began to allow artists much greater freedom.

Even under the strict controls, a number of Soviet artists made noteworthy achievements. Pasternak and Solzhenitsyn each won the Nobel Prize for literature. Director Sergei Eisenstein became famous for his methods of film editing. The music of composers Sergei Prokofiev and Dimitri Shostakovich received worldwide attention. The Moscow Art Theater, founded in 1898, remained the most respected theater company in the Soviet Union. The Bolshoi Theater Ballet and the Kirov Ballet (now the Mariinsky Ballet) continued to earn international fame for the brilliant technical skill and dramatic dancing of their performers.

Economy

The Soviet Union developed the world’s largest centrally planned economy. Until the mid-1980’s, the Soviet Union ranked second after the United States in production of goods and services. The government owned the country’s banks, factories, land, mines, and transportation systems. It planned and controlled the production, distribution, and pricing of all important goods.

Beginning in 1928, the Soviet economy grew rapidly under a series of plans emphasizing industrialization. But improvements in living conditions lagged behind the growth of the economy as a whole. The country’s participation in World War II (1939-1945) caused a major economic setback. The standard of living rose rapidly from 1953 to 1975. But it then remained stalled far below that of most developed countries.

Beginning in the mid-1980’s, General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev and his supporters in the Soviet government began a major reform of the economy called perestroika << `pehr` uh STROY kuh >> , which means restructuring in Russian. Perestroika was an attempt to promote innovation, efficiency, and productivity by reducing government control over industries and introducing elements of a free market economy. In spite of these efforts, economic problems continued until the Soviet Union was dissolved.

Manufacturing.

During the 1920’s, the U.S.S.R. was mainly a farming country. But it had been developing its industry since the late 1800’s, and under communism it became an industrial giant. Only the United States outranked the Soviet Union in the value of manufactured products.

In 1928, Soviet Communist leaders began the first of a series of five-year plans to promote industry. Each plan set up investment programs and production goals for a five-year period. At first, the government chiefly developed factories that produced heavy-industry products, including chemicals, construction materials, machine tools, and steel. Heavy industry expanded rapidly. But housing construction and the production of consumer goods lagged seriously behind.

The Soviet government had widespread control over the operation of individual factories. Government agencies told factory managers which products to make, how many items of each to produce, and where to sell them. Factory managers could reward or discipline workers based on their behavior or expressed views, not just on their work performance. Workers were represented by unions, but in practice, union demands came second to party orders.

Agriculture.

The U.S.S.R. had more farmland than any other country. Its farmland covered more than 21/4 million square miles (5.8 million square kilometers), over a fourth of the entire country. The Soviet Union was one of the world’s two leading crop-producing countries. The United States was the other leader. The U.S.S.R. had more than twice as much farmland as the United States, but U.S. farmland was generally more fertile.

In the 1980’s, about two-thirds of the farmland in the U.S.S.R. consisted of some 22,000 sovkhozy. These huge state farms averaged about 42,000 acres (17,000 hectares) in size. They were operated like government factories, and the farmworkers received wages.

About a third of the farmland in the U.S.S.R. consisted of some 26,000 kolkhozy. The collective farms were overseen by local people appointed to leadership positions. Peasant farmers worked the land according to the orders of their kolkhoz leaders, who in turn answered to local party officials. The kolkhoz farms averaged about 16,000 acres (6,500 hectares). In general, a collective farm supported about 500 households. The collective farmers were paid regular wages in the late Soviet era. Families on collective farms could farm small plots for themselves and sell their products privately.

Foreign trade

played only a small part in the Soviet economy, because the country’s policy was to be self-sufficient. The Soviet Union’s enormous natural resources provided almost all the important raw materials needed. No other country had so much farmland, so many mineral deposits or forests, or so many possible sources of hydroelectric power as the Soviet Union had.

The country’s major exports were lumber and wood products, machinery, natural gas, petroleum, and steel. Its main imports were consumer goods and industrial equipment. Before World War II, the Soviet Union exported grain to pay for imported machinery and other goods. After the war, most of the Soviet Union’s trade was with the countries of Eastern Europe, including Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Poland. The Soviet Union’s chief trading partners outside of Eastern Europe were Cuba, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan.

History

This section traces the major developments of the history of the Soviet Union, from the country’s founding in 1922 until its breakup in 1991. The section begins with the revolution of 1917, which led to Communist rule in Russia. For the history of Russia before 1917 and after 1991, see Russia (History) .

Background of the revolution.

Since the mid-1500’s, Russia had been ruled by absolute monarchs, called czars. By the early 1900’s, however, many people in the empire had turned against the czarist government. Most of the population was comprised of peasants. Russia’s peasants were generally poor, had little education, and were heavily taxed. By 1900, they were desperate for more land and greater opportunities. In the cities, industrial workers—many of whom had originally been peasants—were frustrated with the difficult working conditions and their lack of political representation. Some of the Russian Empire’s many ethnic groups, such as Poles, Jews, and Georgians, resented Russian rule and sought greater independence.

After the mid-1800’s, small groups of educated Russians formed organizations that sought to liberate the people from the czarist government. One group, the Marxists, followed the socialist teachings of Karl Marx, a German social and economic philosopher. The Marxists established the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP). The RSDLP split in 1903, with one group becoming known as the Bolsheviks (later called Communists). The Bolshevik leader was Vladimir I. Ulyanov, who used the name V. I. Lenin.

In 1905, following an economic depression and Russia’s defeat in a war with Japan, discontented groups across the country rose in revolt. Workers and radical political groups formed revolutionary councils, known as soviets. The uprisings forced the czar to establish a fully elected lawmaking body, the Duma. However, the czar resisted the Duma. Frustration with the government grew and opposition groups flourished.

The February Revolution.

World War I began in 1914. Russia fought against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire. During the war, Russia suffered enormous losses, and the people experienced severe shortages of food, fuel, and housing. Townspeople and soldiers grew angry with their leaders, who they believed were mismanaging the war effort.

In March 1917, the people revolted. (The month was February in the old Russian calendar, which was replaced in 1918.) Demonstrations marking International Women’s Day in the capital, Petrograd, turned into violent protests over shortages of bread and coal. (The city of Petrograd was known as St. Petersburg until 1914, was renamed Leningrad in 1924, and again became St. Petersburg in 1991.) Troops were called in to halt the uprising, but they joined it instead. The people of Petrograd turned to the Duma for leadership. Czar Nicholas II ordered the Duma to dissolve itself. The parliament defied the czar and established a provisional (temporary) government. Nicholas had lost all political support, and he abdicated (gave up the throne) on March 15. Nicholas and his family were then imprisoned. Bolshevik revolutionaries killed them in July 1918.

Lenin formed a Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies in Petrograd in March 1917. It was a rival of the provisional government. Many similar soviets were set up throughout Russia. In April, Lenin demanded “all power to the soviets.” In July, following a failed military attack, armed workers and soldiers rioted in Petrograd and tried to convince the Soviet to take power. Lenin refused, but the Bolsheviks were blamed for the violence, and Lenin fled to Finland. Alexander Kerensky, a moderate socialist, became prime minister of the provisional government.

The October Revolution.

Continuing economic chaos and military defeat eroded support for the provisional government. In September 1917, the army commander in chief, General Lavr Kornilov, marched on Petrograd to stop the chaos. The Petrograd Soviet and many city residents rallied against Kornilov and stopped his army. Following Kornilov’s march on the capital, the soviets became more radical. The Bolsheviks became the majority party in the Petrograd Soviet, and won over many army units.

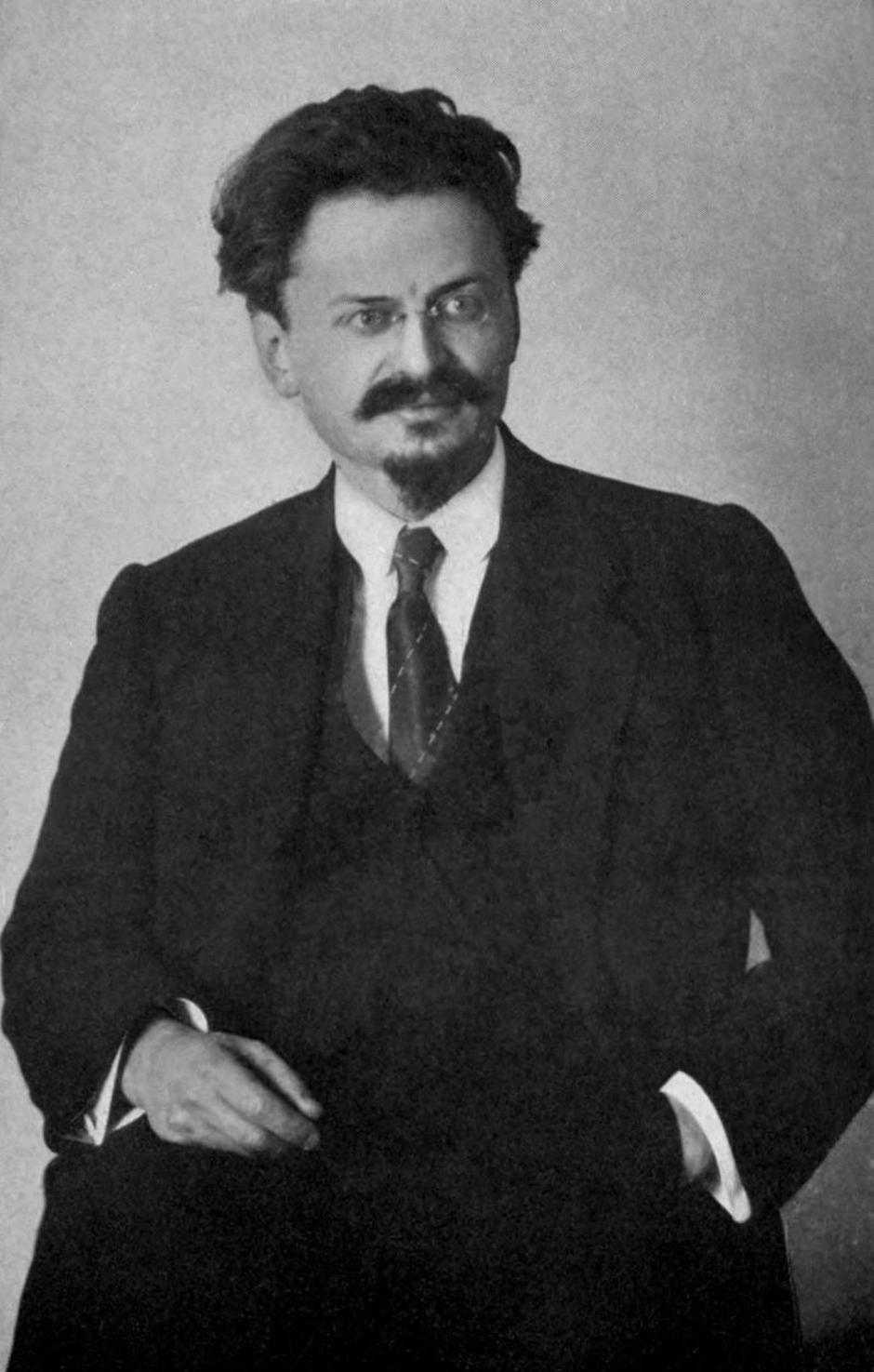

Lenin returned from Finland in October and convinced the Bolsheviks to try to seize power. He hoped a revolution would set off other socialist revolts in Western countries. Lenin’s most capable assistant, Leon Trotsky, helped plan the take-over. On November 7 (October 25 in the old Russian calendar), armed workers and army units loyal to the Petrograd Soviet took over important points in Petrograd. After a bloody struggle in Moscow, the Bolsheviks controlled that city by November 15.

The Bolsheviks formed a new government, headed by Lenin, and sought to appeal to the Russian people. They vowed to end the war. They also endorsed peasants’ seizure of nobles’ lands. For a brief period, Lenin permitted workers to control the factories.

The Bolsheviks began peace talks with Germany. In March 1918, Soviet Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Germany. Under the treaty, Russia gave up large areas, including the Baltic States, Finland, Ukraine, and part of Poland. After the war, Armenia and Georgia set up independent republics.

In 1918, the Bolsheviks moved the Russian capital back to Moscow, which had been the center of government until Czar Peter I made St. Petersburg the capital in 1712. The Bolsheviks also changed the name of their Russian Social Democratic Labor Party to the Russian Communist Party, and later the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. They organized the Red Army, which was named for the color of the Communist flag. The Communists themselves were called Reds. The Cheka, a secret police force, was established.

Civil war.

From 1918 to 1920, Russia was torn by war between the Reds and the various anti-Bolshevik forces, called Whites. The Whites were aided by supplies and troops from the United Kingdom, the United States, Japan, and other countries. Some parts of the former Russian Empire, including Georgia, Ukraine, and parts of Central Asia, also fought against the Bolsheviks in an attempt to assert their independence.

During the war, the Reds proved more organized than the Whites. The Whites included a wide range of political groups that agreed on little and failed to coordinate their efforts. The Bolsheviks focused resources on the war effort. They reimposed control on factory workers and forced peasants to give up their grain. The peasants sometimes resisted the Bolsheviks, but they feared the return of their old landlords if the Whites won, and so they generally supported the Reds. The Red Army grew increasingly effective and ultimately prevailed. The Reds reconquered most of the former Russian Empire, but Poland, Finland, and the Baltic States became independent countries.

The New Economic Policy.

By 1921, seven years of war, revolution, civil war, famine, and invasion had exhausted Russia. Millions of people had died. Agricultural and industrial production had fallen disastrously. About 1 1/2 million Russians, many of them skilled and educated, had left the country. The people’s discontent broke out in the form of strikes, opposition within the Party, and a revolt at the Kronstadt naval base near Petrograd. To protect their revolution, Lenin and his supporters attacked and defeated the Kronstadt sailors and silenced opponents in the Party.

To solve the economic crisis, in 1921 Lenin established a compromise called the New Economic Policy (NEP). Small industries and retail trade were allowed to operate under their own control. The peasants no longer had to give most of their farm products to the government. They paid taxes instead. The government kept control of the most important segments of the economy—banking and heavy industry. The economy recovered steadily under the NEP.

Formation of the U.S.S.R.

In December 1922, the Communist government established the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.). Byelorussia, Transcaucasia, and Ukraine joined with Russia to make up the union’s first four republics.

During the 1920’s, three other union republics were established—Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. In 1936, Transcaucasia was divided into Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Georgia. Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan also became union republics in 1936.

Stalin gains power.

Lenin became seriously ill in 1922 and died in 1924. A struggle for power developed among members of the Politburo. Ultimately, Joseph Stalin out-maneuvered and defeated his rivals. Stalin had become General Secretary in 1922. Using this position, he appointed supporters to important Party positions, giving him backing during Party conflicts.

At first, Leon Trotsky, commander of the Red Army, ranked next after Lenin in power. However, fearing Trotsky would become a military dictator, two other important members of the Politburo—Lev Kamenev and Grigori Zinoviev—allied with Stalin to oppose Trotsky.

Trotsky lost power in 1925. Stalin then helped to expel from the party his own former partners, Kamenev and Zinoviev. By 1929, Stalin had established himself as dictator of the Soviet Union.

Stalin’s policies.

Soviet leaders believed that communism could only be achieved in an industrialized country, but the Soviet Union was still mostly agricultural. During the struggles for power in the 1920’s, Stalin had isolated his rivals by criticizing their plans for industrialization. After he defeated them, he adopted a radical plan for rapid industrialization known as the First Five-Year Plan. The Five-Year Plan was meant to establish a state-run, planned, industrial economy. It had two major components. First, heavy industries, such as railroads, steel, and machine production, would be expanded rapidly and would operate according to state planning. The private enterprises permitted during the NEP period would be taken over by the state. Second, peasant farms would be collectivized and placed under centralized state management. Stalin and his supporters assumed that by collectivizing agriculture, farms would be able to produce more food with less labor. This way, peasant farmers would be freed up to work in new industries. Also, more food would be available to feed industrial workers and to purchase equipment from abroad.

Although costly and somewhat wasteful, the industrialization campaign achieved major gains. It led to quick economic growth across the Soviet Union during the 1930’s. However, the collectivization of agriculture set off a disaster. Soviet officials forced peasants to form collective farms, where they had to give most of their products to state agencies or sell them at low prices. Many peasants resisted. They slaughtered much of their livestock, refused to join the farms, and sometimes attacked state officials. The state responded with force, resulting in thousands of deaths. Millions of peasants were arrested and exiled to remote areas for anti-Soviet resistance.

In 1932 and 1933, a drought struck much of Ukraine, southern Russia, and Kazakhstan. Soviet officials confiscated scarce grain supplies. As a result, historians estimate that 5 million to 8 million people starved to death or were killed in the following unrest, mostly in Ukraine.

State violence.

Many party leaders, especially Stalin, believed that the Soviet Union was full of internal enemies in league with foreign powers. When a party leader was assassinated in 1934, Stalin claimed that it was part of a terrorist plot against the Soviet government. He used the event to justify the arrest, imprisonment, and execution of many citizens, especially those suspected of disloyalty.

From 1936 to 1938, Stalin and his secret police expanded the scope of the violence in what became known as the Great Purge, or the Great Terror. The secret police had been reorganized from the Cheka as the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD). The acronym NKVD comes from the organization’s name in Russian. The NKVD arrested millions of people and sent many to labor camps. They arrested people for a variety of crimes, real or invented. Most of the arrested individuals were innocent of crime, and many were loyal Communists. Nevertheless, police interrogators forced false confessions, often under torture. Private citizens informed on one another to settle personal disputes. Leading figures publicly confessed to crimes they did not commit in a series of public show trials. Hundreds of thousands of people—possibly more than one million—were executed. Fear spread throughout the country. Although the Great Purge was not entirely directed by Stalin, he was its main architect and beneficiary. The result was the elimination of all real or suspected threats to his power.

World War II.

Adolf Hitler became dictator of Germany in 1933, and one of his stated goals was to destroy communism. He believed that Germans deserved more “living space,” which he sought to acquire by invading Poland and the Soviet Union. But Hitler did not want enemies toward both the west and the east. Stalin, for his part, feared a Nazi attack and planned to buy time and gain territory. So in August 1939, the Soviet Union and Germany signed a nonaggression pact, an agreement that neither nation would attack the other. In this pact, the two countries agreed secretly to divide Poland between themselves.

World War II began when Hitler’s troops invaded Poland from the west on Sept. 1, 1939. Two days later, France and the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. Soviet troops invaded Poland from the east on Sept. 17, 1939, and soon occupied eastern Poland. On November 30, the U.S.S.R. attacked Finland. The Soviet Union won much Finnish territory, and in March 1940, Finland was forced to agree to a peace treaty.

In June 1940, the Red Army moved into Bessarabia (then part of Romania) and the Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The Baltic countries were forced to become republics of the Soviet Union, and most of Bessarabia became part of the new Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.

On June 22, 1941, a huge German force, together with troops from Romania, Hungary, and other countries, invaded the U.S.S.R. German warplanes destroyed much of the Soviet air force, and Hitler’s armies drove deep into Soviet territory. In September, the Germans captured Kiev (now Kyiv) and attacked Leningrad. In December, the Germans came close to Moscow.

By early 1942, however, the Red Army had stopped the Germans outside Moscow and driven them back. After the Battle of Moscow, the conflict became a war of attrition, in which each side slowly exhausted the other’s energy and resources, without achieving any substantial gains.

The United Kingdom and the other Western Allies welcomed the U.S.S.R. as a partner in the war against Germany. Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States began shipping supplies to the Soviet Union. The United States had joined the Allies in December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

The five-month Battle of Stalingrad (now Volgograd), which began in late August 1942, was the war’s largest and bloodiest battle. By the time the Germans surrendered, they and their allies had suffered over 800,000 casualties (dead, wounded, captured, and missing). Soviet casualties were more than one million, including thousands of civilians.

After the victory at Stalingrad, the Red Army advanced steadily across Eastern Europe and into Germany. The attack on Leningrad lasted until January 1944, when the Germans were finally driven off. As the Red Army swept across Eastern Europe, it freed many countries from German control, including Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. In April 1945, Soviet troops began to attack Berlin. Hitler died by suicide on April 30. Berlin fell to the Red Army on May 2, and Germany surrendered to the Allies on May 7. The war in Europe was over.

On August 8, the U.S.S.R. entered the war against Japan, occupying Japanese-held Manchuria and part of Korea. The United States had dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima two days before, and dropped another on Nagasaki on August 9. Japan surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945, marking the end of World War II.

Results of the war.

The Soviet Union played a key role in the defeat of Nazi Germany. Soviet forces inflicted roughly three-fourths of German wartime military losses. The human cost to the Soviet Union, however, was enormous. Historians estimate that from about 20 million to 27 million Soviet citizens, including troops and civilians, died as a result of fighting, disease, famine, displacement, and other war-related causes. No other country suffered so many casualties. Whole regions of the U.S.S.R. lay in ruins, and much of the Soviet economy was shattered.

Beginnings of the Cold War.

During World War II, Stalin had promised United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister WInston Churchill to help promote peace and freedom throughout the world. As the Soviet Union’s military position improved, Stalin became less agreeable. He insisted on having “friendly”—meaning pro-Soviet—governments in Eastern Europe, especially in Poland, and on making sure Germany remained disarmed. After the war, the Soviet Union and the Western Allies came to oppose each other on many issues, especially the future of Germany and Poland. The Soviets occupied the eastern zone of Germany and a sector of Berlin. East-West relations in Germany became tense. The U.S.S.R. set up a Communist police state in its zone and blocked Western efforts to unite Germany. Red Army units remained in the Eastern European countries they had freed from German control and helped communist governments take power in these nations.

The communists in Eastern European countries formed what seemed to be coalition governments. In such governments, two or more political parties share power. But the communists, supported by the Soviet Union, seized important government positions and held the real power. Their strength grew, and they did not permit free elections. By early 1948, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania had become Soviet satellites (countries controlled by the Soviet Union). The U.S.S.R. also tried to control communist governments in Albania and Yugoslavia.

The U.S.S.R. cut off nearly all contacts between its satellites and the West. Its barriers against communication, trade, and travel came to be known as the Iron Curtain. Distrust grew between East and West. The Cold War, a struggle between the two sides for international influence and allies, spread through Europe and many other regions of the world.

The rise of Khrushchev.

Rapid Soviet industrialization resumed after World War II under new five-year plans. Restrictions on the peasants, which had been loosened during the war, again became severe. Rebuilding heavy industry took priority over producing consumer goods. The collective farms were reorganized and enlarged. Stalin also began a new wave of political arrests and executions. Then, on March 5, 1953, he suddenly died after a stroke.

No single leader immediately replaced Stalin. A collective leadership of several men ruled. For almost two years, Georgi Malenkov served as premier. During this period, a struggle for power developed among Malenkov and other leading Communists. Nikita Khrushchev served as secretary of the Communist Party beginning in September 1953. Khrushchev outmaneuvered Malenkov, who was forced to resign in 1955. In 1958, Khrushchev became premier as well as Communist Party leader.

At the 20th Communist Party Congress in 1956, Khrushchev openly criticized Stalin and began a program meant to distance the party from the former leader. This program was known as destalinization. Khrushchev accused Stalin of murdering innocent people and of faulty leadership. Buildings, cities, and towns that had been named for Stalin were renamed. In addition, pictures and statues of Stalin were destroyed.

Khrushchev’s policies

differed greatly from Stalin’s. Khrushchev was unpredictable. He was likely to use crude language and change policies suddenly. Khrushchev thought Soviet socialism could be more humane. Under his rule, most Soviet prison camps were closed, and the secret police, now called the KGB, did not spread terror. Writers, scientists, and scholars were permitted greater freedom of expression in a period known as the Thaw. The workweek was shortened to about 40 hours, and workers were allowed to quit or change jobs. Khrushchev also sought to raise the people’s standard of living through greater production of clothing, food, appliances, and other consumer goods.

Khrushchev also tried to restructure the Party to encourage more public participation. However, he did not permit outright disagreement, and used force to stop opposition. In 1956, Soviet forces invaded Hungary to crush a democratic-socialist movement there, killing thousands of people.

Foreign affairs under Khrushchev.

Khrushchev’s foreign policy was, at first, less confrontational than Stalin’s, and Soviet relations with the West improved. Unlike other Communist leaders, Khrushchev denied that war with the West was necessary for communism to triumph. In 1956, Khrushchev announced a policy of peaceful coexistence. He described it as a means of avoiding war while competing with the West in technology and economic development. Khrushchev eased restrictions on communication, trade, and travel across the Iron Curtain. He made friendly visits to several Western countries, including the United States. But the U.S.S.R. still tried to expand its influence by encouraging revolts, riots, and strikes in noncommunist countries.

China’s communist government believed war with the West was necessary and criticized the “soft” Soviet policy.The dispute between the two communist powers caused a lasting split between them. In 1969, violent border clashes occurred between the two countries in the Far East.

Under Khrushchev, the Soviet Union still competed with the United States for power and influence. Khrushchev encouraged communist revolutions in the developing world, especially in Africa and Latin America. The Soviet Union continued to develop its conventional and nuclear military capabilities. It also invested heavily in space exploration.

Relations with the United States.

Under Khrushchev’s leadership, the Soviet Union came very close to starting a nuclear war. In 1960, he clashed with U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower after an American surveillance plane was shot down over Soviet territory.

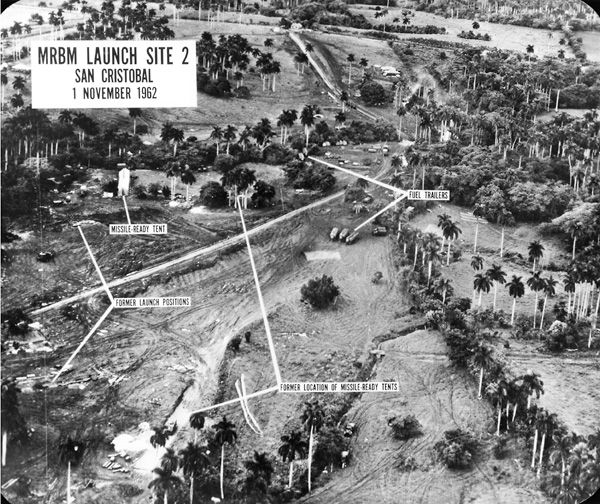

Another crisis occurred in 1962. The United States learned that the Soviet Union had missile bases in Cuba. These bases were capable of launching nuclear attacks against the United States or other parts of the Western Hemisphere. United States President John F. Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba and demanded the removal of all the missiles and bases. The Soviets removed their missiles in exchange for the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear missiles from Turkey and Kennedy’s promise that the United States would not invade Cuba.

In 1963, the U.S.S.R., the United Kingdom, and the United States signed a treaty prohibiting all nuclear weapons tests except those conducted underground. Also in 1963, the Soviet Union and the United States set up a direct teletype connection called the hot line between Moscow and Washington, D.C. A teletype is a telegraphic device. They hoped it would help prevent any misunderstanding from leading to war.

Brezhnev comes to power.

Although Khrushchev improved Soviet relations with the West, many of his other policies failed. Farm output lagged, and in 1963 the U.S.S.R. began to buy wheat from the West. Economic growth slowed, and people criticized the many poorly made products. Also, the split with China and the retreat in Cuba drew criticism. Some Party leaders were also opposed to Khrushchev’s destalinization policies. In 1964, a conspiracy among high-ranking Communists led to the overthrow of Khrushchev. Khrushchev was replaced by Leonid Brezhnev as Communist Party head and by Aleksei Kosygin as premier. During the early 1970’s, Brezhnev’s power increased at Kosygin’s expense. By the mid-1970’s, Brezhnev was more powerful.

The new leaders took power amid worsening Soviet relations with a number of countries. In Eastern Europe, several Soviet satellite countries sought to lessen Soviet control and follow their own policies. For example, the government of Czechoslovakia began a reform movement to give the people more freedom. In 1968, Soviet troops invaded Czechoslovakia and crushed this movement.

The Soviets continued to expand their influence in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Soviet Union supplied equipment and advisers to communist groups that sought to gain, or keep, control in Angola, Ethiopia, and other countries in Africa.

Like Khrushchev, Brezhnev and his supporters tried to step up the production of consumer goods and the construction of housing. The Soviet economy made some gains, though it never met government goals. Nevertheless, the Soviet economy under Brezhnev was fairly stable, and Soviet citizens enjoyed an average, if not prosperous, standard of living.

However, the Soviet Union under Brezhnev faced many long-term problems. The development of advanced technologies, especially computers, fell far behind that of the United States, Western Europe, and Japan. The rate of growth of Soviet industrial production began to decline, and workers’ productivity slowed. Also, agricultural production suffered from planning problems and a series of disastrous harvests. As a result, the U.S.S.R. continued to import grain from the West. The Soviet government depended increasingly on revenue from oil exports to finance grain imports, consumer goods, and its enormous military force. Corruption and mismanagement in the government, together with major health and environmental problems, also undermined support for the Communists.

Détente.

Brezhnev pursued a policy of friendlier relations with the West. This easing of tensions between East and West became known as détente << day TONT >> . Soviet leaders sought detente chiefly to improve the Soviet Union’s economic and military position. They wanted to sell natural resources abroad and acquire advanced Western technology. Doing so allowed Party leaders to use income from exports—especially from oil sales—to prop up their flawed economy.

Détente also had a political component. In 1972, the Soviet Union and the United States signed two agreements to limit nuclear arms. These agreements resulted from a series of meetings called the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT). In 1975, the leaders of the Soviet Union and many other countries had signed agreements known as the Helsinki Accords. According to the agreements, the U.S.S.R. agreed to honor such basic human rights as freedom of thought and freedom of religion in exchange for recognition of the borders established at the end of World War II.

Following the agreements, Soviet writers and other intellectuals protested government violations of the people’s rights. The Soviet government arrested many of its critics. It sentenced some of them to prison or to mental hospitals. Others were sent to live in remote areas, and a few were expelled from the country.

The collapse of detente

began in the late 1970’s. United States President Jimmy Carter strongly supported human rights. Under Carter, U.S. relations with the Soviet Union and other countries that violated their citizens’ human rights became strained. In late 1979 and early 1980, Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan to try to keep that country’s pro-communist government in power. The United States protested the invasion by limiting shipments of wheat to the U.S.S.R. and by boycotting the 1980 Summer Olympic Games held in Moscow.

Soviet-U.S. relations worsened in 1981. That year, U.S. President Ronald Reagan called for a U.S. military build-up to match an expansion of Soviet arms under Brezhnev. Soviet leaders feared that this build-up would give the United States a military advantage.

The rise of Gorbachev.

The older generation of Soviet leaders, who had been trained under Stalin, had nearly all died by the mid-1980’s. Kosygin died in 1980. Brezhnev died in 1982 and was succeeded by Yuri Andropov, who died in 1984. Konstantin Chernenko replaced Andropov, but he died in 1985. Mikhail Gorbachev then became head of the Communist Party. At age 54, Gorbachev became the first member of a new generation of Soviet leaders to head the country.

Gorbachev’s reforms.

Brezhnev and his immediate successors had not been interested in making significant changes to the system, despite the Soviet Union’s many problems. Gorbachev, on the other hand, believed that the Soviet Union needed fundamental reforms. He wanted to change the Soviet economy to achieve higher living standards and to maintain the Soviet Union’s superpower status. He believed that the Soviet Union could achieve a humane, democratic form of socialism, rather than a repressive one.

The central part of Gorbachev’s reform program was known as perestroika (restructuring). Begun in 1985, perestroika was intended to restructure the Soviet economy to stimulate growth and increase efficiency in Soviet industry. But the reforms soon encountered resistance. Ultimately, they made things worse. Shortages of basic goods increased. Inflation grew, and hoarding became widespread.

A related aspect of Gorbachev’s program was a reduction in Cold War tensions. Gorbachev wanted to redirect resources from foreign competition toward internal reform. Beginning in 1985, he called for “peaceful coexistence,” halted the deployment of new missiles, and moved to reduce military expenses. In 1987, Gorbachev and Reagan signed a treaty agreeing to reduce the size of U.S. and Soviet nuclear forces. From May 1988 to February 1989, Soviet troops withdrew from Afghanistan. In 1991, Gorbachev and U.S. President George H. W. Bush signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). This agreement, which entered into force in 1994, ordered a reduction in the numbers of U.S. and Soviet long-range nuclear weapons.

The most striking change was a new policy of openness called glasnost << GLAHS nawst >> . Gorbachev introduced glasnost to help win popular support for his policies and overcome resistance to perestroika in the Communist Party and the Soviet government. Glasnost made it possible to discuss political and social issues more critically and openly . Also, greater freedom of expression in literature and the arts was allowed, and books by opponents of Communism and previously banned Western authors became available in stores.

Perestroika and glasnost provoked resistance among many Communist Party leaders. To block this resistance and to make the government more democratic, Gorbachev tried to shift power away from the party toward the Supreme Soviet, the U.S.S.R’s national legislature. The Supreme Soviet had historically been under the Communist Party’s control. However, under Gorbachev it was renamed the Congress of People’s Deputies. In 1989, elections to the Congress were held in which non-Communist candidates were permitted for the first time. Many top Party officials were defeated.

In 1990, the Soviet government voted to permit the formation of non-Communist political parties in the Soviet Union. The Soviet government created the office of president of the U.S.S.R. The president became the head of the central government and the most powerful person in the Soviet Union. The Congress of People’s Deputies elected Gorbachev as the first president of the U.S.S.R.

Threats to unity.

Communist governments in Eastern Europe faced strong popular opposition. Gorbachev was unwilling to use force to keep them in power. Beginning in 1989, such governments collapsed across Eastern Europe, ending the era of Soviet control.

Popular independence movements were also strong in many regions of the Soviet Union, particularly in the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. In 1990, Lithuania declared independence, and Estonia and Latvia called for a gradual separation from the Soviet Union. By the end of 1990, all 15 republics had declared that laws passed by their legislatures took precedence over laws passed by the central government. In June 1991, the Russian Republic elected its own president, Boris Yeltsin.

To prevent further disintegration, Gorbachev proposed a new union treaty that would have given more independence to the republics. He and 10 republic-level leaders reached agreement on a new treaty in July 1991. It was to be signed by five of the republics on August 20.

On August 19, before the treaty could be signed, conservative officials of the Communist Party staged a coup (overthrow) against Gorbachev’s government. The coup leaders imprisoned Gorbachev and his family in their vacation home. However, the coup was poorly organized. Yeltsin led opposition to the coup, which collapsed on August 21. Yeltsin’s role in defying the coup increased his power and prestige both at home and abroad.

After the coup, Gorbachev returned to the office of president but never regained full power. He then resigned as head of the Communist Party.

The breakup of the Soviet Union.

The collapse of the coup further eroded support for the union and the party. The Congress of People’s Deputies formed a transitional government to maintain the unity of the country until a new union treaty could be written. The transitional government recognized the independence of the Baltic republics in September 1991. By November, 13 of the 15 Soviet republics—all except Russia and Kazakhstan—had declared independence. Eleven of the republics—all but the Baltic republics and Georgia—agreed to remain part of a new, loose confederation of self-governing states. Many of the republics, however, viewed this confederation as only a temporary arrangement.

The final blow to Soviet unity came in December 1991. On December 8, Yeltsin and the presidents of Belarus and Ukraine met in Minsk, Belarus. The leaders announced that they had formed a new, loose confederation called the Commonwealth of Independent States. They declared that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist and invited the remaining republics to join the commonwealth. On December 21, another eight republics joined. On December 25, Gorbachev resigned as Soviet president, and the Soviet Union was formally dissolved.

In 1993, 12 leaders of the 1991 failed coup against Gorbachev went on trial. The Russian government had charged them with treason and plotting to seize power. In February 1994, the Russian parliament granted amnesty to the coup leaders and freed them.