United States, History of the. The history of the United States is a story about the lives of many groups of people. It includes accounts of conquest and struggle, mistreatment and resistance, creativity, bold action, and courage on the part of millions of people. The men and women who came to America and built the new nation called the United States had many reasons for their actions. Some wanted to get rich. Others wanted to improve people’s lives. Still others wanted religious or other freedoms, or simply wanted to be left alone. Many found inventive ways to adapt to conditions they did not expect.

The United States has always been a place of diversity and variation. The first people to live in North America—now known as Indians or Native Americans—arrived thousands of years ago. Long before the arrival of the Europeans and Africans in the 1600’s, these peoples had established many different societies. Hundreds of separate Indigenous (native) groups spoke different languages, practiced their own religions, and pursued various economic activities. The groups maintained complex trading and diplomatic networks, some spanning the continent. The Europeans and Africans were similarly diverse, as were the Asians who began to arrive in the 1800’s.

Spain had started to colonize parts of North America in the 1400’s and 1500’s, mainly by sending soldiers and missionaries to enslave Native Americans and convert them to Christianity. In the 1600’s, England (which later became part of Great Britain and later still part of the United Kingdom) began sending settlers. These colonists took land from native peoples and, in many places, imported Africans as slave laborers. The British colonies expanded along the eastern coast of North America, eventually stretching from present-day Maine to Georgia. The settlers found British rule agreeable until conflicts in the 1760’s and 1770’s drove them to declare their independence from Britain. They established the United States of America in 1776. At the start, the survival of the new nation was in doubt. The colonists had to defeat the mighty British Empire in the American Revolution (1775-1783) to establish their claim to independence.

The American people dedicated their new nation to the principles of democracy, freedom, equality, and opportunity. From the start, these promises attracted people from other countries. Millions of immigrants, most of them from Europe, poured into the United States. At the same time, the slave trade brought hundreds of thousands of Africans against their will. Waves of white settlers invaded the lands of Indigenous peoples as they moved westward.

Rapid population growth, resulting from immigration and natural increase, was accompanied by rapid economic growth. Wherever they went, American settlers cut down forests and plowed vast stretches of prairie to establish farms. They found minerals and other valuable resources, and built towns nearby. Cities grew along the main transportation routes, and business and industry prospered. This rapid expansion made the United States one of the largest nations in the world in both size and population.

The United States has often been divided, largely because it has been so diverse. Americans have often found themselves separated by race, religion, and other differences. In the North, most states abolished slavery during and after the American Revolution. In the South, slavery expanded. In the West, settlers and Native Americans fought bitter wars when native groups resisted expansion into their lands. In the 1860’s—less than 100 years after the American Revolution—the very survival of the United States was threatened. Eleven Southern states withdrew from the Union and tried to establish an independent nation. The American Civil War (1861-1865) between the North and South followed. The North won the war, and the nation survived, though hundreds of thousands of people died in the fighting.

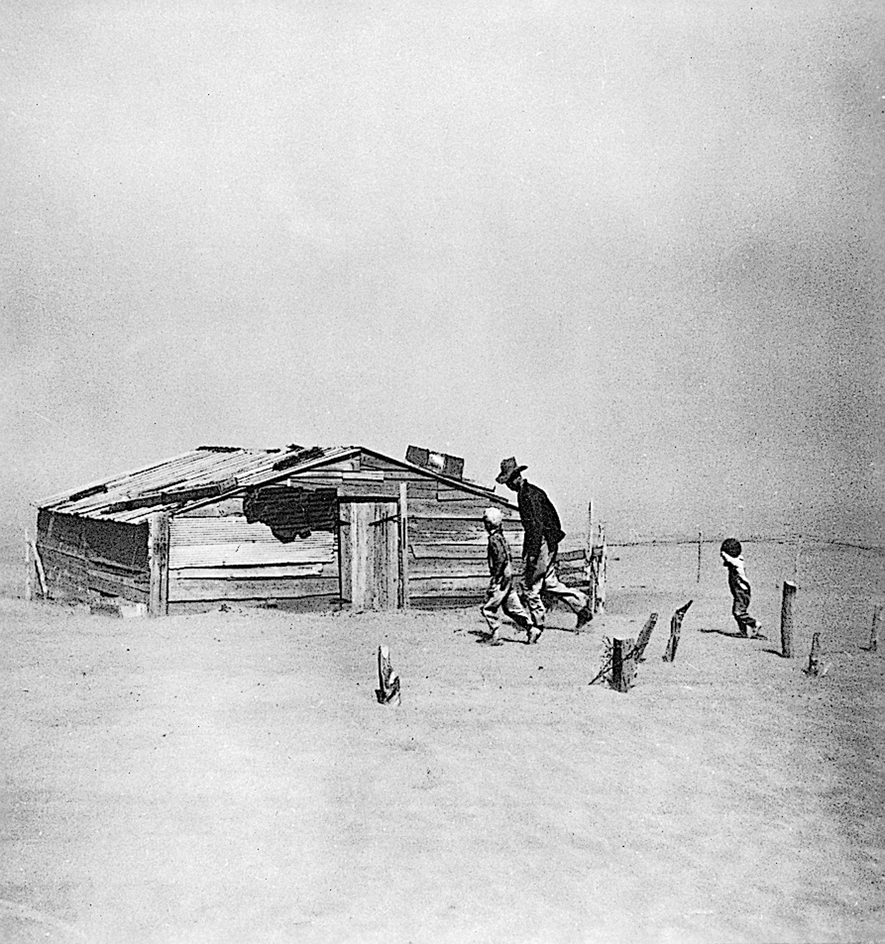

The economic growth of the United States, though rapid, has not always been smooth. At times, depressions brought the economy to a standstill. The worst depression struck in the 1930’s. Huge numbers of Americans lost their jobs and homes and fell into poverty.

In the 1900’s, the United States became one of the world’s strongest military powers. As such, it took a more active role in the world. This role led the United States into two world wars and a series of other conflicts. The Vietnam War (1957-1975) was the first foreign war in which U.S. combat forces failed to achieve their goals. After the war, many Americans questioned what the country’s role should be in world affairs. They asked the same question again after terrorists from the Middle East attacked New York City and Washington, D.C., in 2001.

In the early 2000’s, the United States faced many challenges. These challenges included the existence of poverty amid great wealth; continuing racial, ethnic, and religious discrimination; and pollution of the environment. The threat of terrorism heightened disputes over national security and the protection of civil liberties. Nevertheless, Americans held a deep pride in their country, and most believed it could overcome these challenges.

America before colonial times

For thousands of years, Native Americans were the only inhabitants of the Western Hemisphere. Most historians believe the first groups were hunters who came to North America from Asia at least 15,000 years ago by crossing a narrow strip of land that then linked Siberia to Alaska. After the land bridge sank underwater, people crossed the Bering Strait by boat. The migrants spread southward and eastward across North and South America. By A.D. 1000, ancestors of the Inuit—another Asian people—lived in what is now northern Alaska. The Inuit spread eastward across the Arctic but remained in the Far North, near the Arctic Circle.

The Vikings were probably the first Europeans to reach America. A band of these seafarers explored and temporarily settled part of the east coast of North America about 1,000 years ago. But serious exploration and settlement of America by Europeans did not begin for another 500 years, until 1492. Then, the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus sailed westward from Spain, seeking a short sea route to Asia. He found, instead, a vast New World. After Columbus, European explorers, soldiers, and settlers flocked to America.

The first Americans.

Scholars do not know how many Indigenous people lived in the Americas in the 1400’s, when Europeans reached what they called the New World. Many experts believe there were from 30 million to 75 million people living in all of North and South America, with about 1 million to 5 million in what is now the United States. But some estimates run as high as 118 million for the Americas, including more than 15 million in the United States.

The Native Americans formed hundreds of cultures, with many different languages and ways of life. Some groups, including the Aztec, Inca, and Maya in the south, established advanced civilizations. They erected cities with huge, magnificent buildings. They also accumulated gold, jewels, and other riches. North of Mexico, most Native Americans lived in small villages and relied on hunting or farming. The main crops were corn, beans, and squash. In the dry Southwest, the Anasazi built large towns and vast irrigation systems. In the wetter and cooler climate of what is now the Midwest, the Mississippians also built large towns and complex cultures. The fortified city of Cahokia, in present-day Illinois, may have had a population of 10,000 to 20,000 at its peak. In the 1500’s, Spanish explorers visited flourishing Mississippian towns in present-day Alabama, Georgia, and Oklahoma.

In the Northeast, from Canada to North Carolina, most Indigenous people spoke either the Iroquoian or Algonquian languages. The Iroquois lived in permanent villages and combined farming with hunting and gathering wild plants. They had great military power. By the early 1600’s, five Iroquois nations had founded the Iroquois League, a diplomatic arrangement that increased their strength.

The Algonquian peoples were spread over a large area but were less powerful. Some Algonquian lived in permanent villages and mixed farming with fishing, hunting, and gathering. Others had more mobile lifestyles. The Algonquian were divided into many tribes. One of their largest organizations was the Powhatan Confederacy in Virginia. Under the Algonquian leader Powhatan, this confederacy had united more than 30 tribes with about 15,000 people by 1607, when the first Europeans reached their land.

European discoveries.

About A.D. 1000, a Norse people called the Vikings, who had settled in Greenland, became the first white people to reach the North American mainland. Led by Leif Eriksson, they sailed to what is now the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador and explored the area. But they did not establish permanent settlements.

By the time of Columbus’s voyage in 1492, most Europeans did not know that the Viking expeditions had taken place, nor that the Western Hemisphere even existed. The Italian trader Marco Polo’s Description of the World (1298) had described fabulous wealth and advanced technologies in the Far East. Inspired by such reports, Europeans became interested in finding a short sea route to China, Japan, and India.

Columbus, an Italian navigator, believed he could find a short route to the East by sailing west. Financed by the Spanish king and queen, he set sail westward from Spain on Aug. 3, 1492. Columbus reached land on October 12 and assumed he had arrived in the Far East. Actually, he landed on an island in the Bahamas, just east of the North American mainland. He explored other Caribbean islands, still thinking he was in Asia. Leaving a crew on the island of Hispaniola, he returned to Spain and published a widely read account of his voyage. In 1493, Columbus returned to Hispaniola with a large army. Over the next few years, he conquered and enslaved the Taino people. The Taino were a subgroup of the Arawak, who lived on most of the Caribbean Islands. Many Indigenous people died from exposure to European diseases. The Arawak population of about 300,000 in 1492 fell to about 500 in 1548. Steep population drops—resulting from war, enslavement, and especially epidemics of European diseases—also struck other Indigenous peoples across the Americas.

Columbus died in 1506. He still believed he had sailed to an unknown land in the Far East. Other Europeans called this land the New World and honored Columbus as its discoverer. Europeans also called it America, after the Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, who claimed to have explored the land in 1497. However, many scholars have questioned Vespucci’s claims of discovery.

Exploration and early settlement.

The discovery of America caused great excitement in Europe. To many Europeans, the New World offered opportunities for wealth, power, and adventure. European rulers and merchants wanted to gain control of the hemisphere’s resources to add to their wealth. Rulers also sought New World territory to increase their power. Christian missionaries wanted to spread their religion to the Native Americans. Explorers saw the New World as a place to seek adventure, fame, and fortune. Before long, Europeans from several countries sailed across the Atlantic Ocean to explore America and set up trading posts and colonies. For details, see Exploration.

The Europeans often treated native people cruelly. But even when they were friendly, their arrival was disastrous for the Native Americans, who had never encountered many diseases that were common in Europe. Horrifying epidemics of smallpox, influenza, and other illnesses wiped out Indigenous populations across the Americas.

The Spanish and Portuguese.

During the 1500’s, the Spanish and Portuguese spread out over the southern part of the Western Hemisphere in search of gold, silver, and jewels. The Spaniards conquered the Inca of Peru, Maya of Central America, and Aztec of Mexico. The Portuguese gained control of the Guarani and other groups in what is now Brazil. By 1600, Spain and Portugal controlled most of the Western Hemisphere from Mexico southward.

Also during the 1500’s, Spaniards moved into what is now the southeastern and western United States. They did not discover riches there, but they took control of Florida and the land west of the Mississippi River. In 1526, the Spanish founded San Miguel de Gualdape, the first European settlement in the present-day United States. Historians believe the colony stood on the coast of what is now South Carolina or Georgia. The Spanish soon abandoned it because of disease or bad weather. In 1565, they founded St. Augustine, Florida, the oldest permanent European settlement in what is now the United States. They also founded missions and other settlements in the West and South. See Mission life in America; Spain (The Spanish Empire).

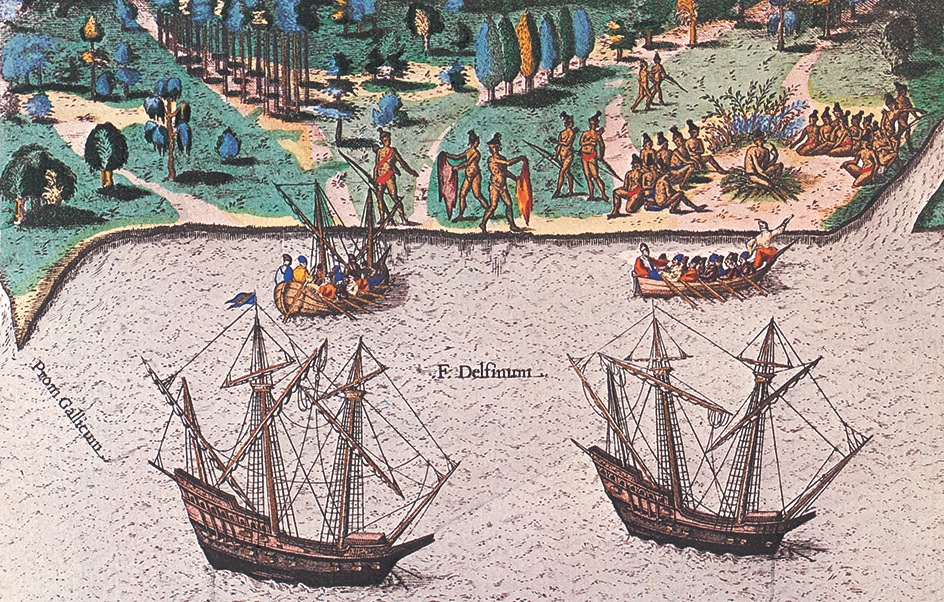

The English and French

began exploring eastern North America around 1500. At first, both nations sent only explorers and fur traders. But after 1600, they began founding permanent settlements. The French settlements were chiefly in what is now Canada, but also in the territory from the Great Lakes to Louisiana. The English settlements included the 13 colonies that formed the United States in 1776.

For years, Britain and France struggled for control of Canada and the land between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River. They also competed with each other for trade with Native American groups.

Impact on Native Americans.

Because the early explorers spread diseases that caused huge epidemics among Indigenous people, the settlers who followed often moved onto lands that were sparsely populated. Some found cleared fields and recently abandoned towns that helped them recognize the best places to settle.

Many Native Americans traded with the early European settlers and helped them survive in the wilderness. At first, the Indigenous people did not realize how great a threat the Europeans were, mainly because the newcomers seemed unable even to feed themselves. As growing numbers of settlers pushed westward, Native Americans realized that they presented a grave threat, and white and Indigenous people became enemies. Even so, they maintained economic and diplomatic links.

Contact with the Europeans changed Native American life in many ways. Trade with the Europeans, who wanted furs and deerskins to export to Europe, caused Indigenous people to hunt and trap many more animals than before. Once they exhausted local supplies of beaver and other animals, they invaded the territories of other tribes, causing wars between Native American groups. Trade with the Europeans also led many Native Americans to replace their traditional technologies with imported ironwork, cloth, and guns. This switch made Native Americans dependent on trade with Europeans. Disease was the most devastating European import into the Americas. However, large supplies of cheap alcohol from European traders also brought harm to many Indigenous people.

The American Colonies (1607-1753)

The first English attempt to establish a colony in what is now the United States took place in 1585. Sir Walter Raleigh sent settlers to Roanoke Island, off the coast of North Carolina. But this attempt at colonization failed (see Lost Colony).

In 1607, a band of about 100 English colonists reached the coast near Chesapeake Bay. They founded Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in North America (see Jamestown). During the next 150 years, a steady stream of colonists arrived and settled near the coast. Most were British, but they also included people from France, Germany, Ireland, and other countries. Many were Africans who were kidnapped from their homes and brought to the colonies as slaves.

The earliest colonists faced great hardship and danger. They suffered from lack of food and from disease. Sometimes, the colonists maintained peace and trade with native people. Other times, they fought fierce wars with them. Soon, however, the colonies prospered. They established small family farms and large slave-labor plantations; built towns, roads, and churches; and began many small industries. Their populations grew, and their wealth increased.

The colonists developed political practices and social beliefs that have had a major influence on the history of the United States. Some established democratic governments. Most placed a high value on individual liberty and respected hard work as a means of getting ahead. Many had the unsupported belief that white Europeans were superior to Native Americans and Africans. As a result, they felt they had the right to take Native American land by violence and to force African labor through the institution of slavery.

In the early 1600’s, the English king began granting charters, documents bestowing the right to establish colonies in America. The charters went to companies of merchants and to individuals called proprietors. The merchant companies and proprietors were responsible for recruiting people to settle in America and, at first, for governing them. By the mid-1700’s, most of the settlements had been formed into 13 colonies. Each had a governor and a legislature, but was under the ultimate control of the British government.

The Thirteen Colonies stretched from what is now Maine in the north to Georgia in the south. They included the New England Colonies of Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire; the Middle Colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware; and the Southern Colonies of Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia. (Some historians classify Virginia and Maryland, which lie along Chesapeake Bay, as Chesapeake Colonies.)

Virginia and Maryland

were among the earliest British colonies. They were established for different reasons, but they developed in much the same way.

Virginia was the largest of the Thirteen Colonies. It began with the Jamestown settlement of 1607. The Virginia Company of London (later shortened to Virginia Company), an organization of English merchants, sent settlers to America hoping they would find gold and other riches. But the settlers found no riches and faced great hardships. Captain John Smith played a major role in helping the colony survive its early days, mainly by forcing the colonists to grow food. In 1612, some Jamestown colonists began growing tobacco, which the Virginia Company sold in Europe. Virginia prospered as tobacco production increased in response to rising European demand. English settlers came in droves and established new farms and settlements.

Maryland was founded by the Calverts, a family of wealthy Roman Catholics. Catholics were persecuted in England, and the Calverts wanted a place where they could have religious freedom. In 1632, Cecilius Calvert became proprietor of the Maryland area. Colonists, led by Cecilius’s brother, Leonard Calvert, established the first Maryland settlement in 1634. The Maryland settlers also raised tobacco. As production increased, their colony prospered.

The settlers of Virginia and Maryland made important strides toward self-government and individual rights. The Virginians appealed to the Virginia Company for a voice in their local government. The company wanted to attract newcomers to its colony, and so it agreed. In 1619, it established the House of Burgesses, the first representative legislature in America. Maryland attracted both Catholic and Protestant settlers. In 1649, the Calverts granted religious freedom to people of both faiths. This grant was the first law in North America calling for religious toleration.

Virginia and Maryland also began a practice that violated individual rights—slavery. By the 1680’s, planters in both colonies had begun to buy enslaved Africans and force the Africans to work on their lands.

New England.

Puritans, originally financed by English merchants, founded the New England Colonies. Puritans were English Protestants who faced persecution because of their opposition to the Church of England, their homeland’s official church. See Puritans.

In 1620, a group of Separatists (Puritans who had separated from the Church of England) and other colonists settled in New England. Called Pilgrims, they founded Plymouth Colony, the second permanent English settlement in North America. Between 1628 and 1630, Puritans founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony at what are now Salem and Boston. Plymouth became part of Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691. See Plymouth Colony; Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Settlers spreading out from Massachusetts founded the other New England Colonies. Connecticut was first settled in 1633 and became a colony in 1636. Colonists took up residence in Rhode Island in 1636, and Rhode Island became a colony in 1647. New Hampshire, first settled in 1623, became a colony in 1680. Important Puritan leaders included governors William Bradford of Plymouth and John Winthrop of Massachusetts, and Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island.

Life in New England centered on towns organized around churches. Each family farmed its own plot of land, but they all lived close together in a town so they could walk to church. Most of the New England colonists farmed for a living. But they also developed a thriving shipping business and started many small industries, including fishing, lumbering, and crafts. There were few enslaved Africans in New England.

The Puritans of New England did not tolerate religious dissent, but they made important contributions to democracy in America. In 1620, the Pilgrims established the Mayflower Compact, an agreement among the adult males to provide “just and equal laws” for all (see Mayflower Compact). The Puritans created a democratic political system in which all officials were elected. At town meetings, most male adults could participate in decisions.

The Middle Colonies.

Soon after English settlement began, the Dutch founded New Netherland, a trading post and colony that included what are now New York and northern New Jersey. They started a settlement in New York in 1624 and in New Jersey in 1660. In 1638, the Swedes established New Sweden, a settlement in present-day Delaware and southern New Jersey. The Dutch claimed New Sweden in 1655. In 1664, the English took over New Netherland and New Sweden.

King Charles II of England gave the New York and New Jersey territory to his brother, James, Duke of York. Friends of the duke founded huge farming estates in New York along the Hudson River. New York City developed from the Dutch city of New Amsterdam. It became a shipping and trading center. The Duke of York gave New Jersey to two of his friends. They allowed much political and religious freedom, and New Jersey attracted many settlers.

Swedes established a small settlement in what is now Pennsylvania in 1643. In 1681, a wealthy Englishman named William Penn received a charter that made him the proprietor of Pennsylvania. Penn was a member of the Quakers, a religious group that was persecuted in many countries (see Quakers). At Penn’s urging, Quakers and other settlers who sought freedom flocked to Pennsylvania. Penn carefully planned settlements in his colony, and Pennsylvania thrived. Philadelphia became the largest city in colonial America. Penn also became proprietor of the Delaware region.

Most settlers in the Middle Colonies were farmers, whose main crop was wheat. The colonies developed thriving commerce and small industries. They had more enslaved Africans than New England had, but far fewer than the South. The Middle Colonies contributed to democracy and religious freedom in America. Adult white males could vote for most officials. Most colonists were Protestants but belonged to many different churches.

North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia.

About 1650, colonists from Virginia established a settlement in northern Carolina, the land between Virginia and Florida. In 1663, King Charles II gave Carolina to eight of his nobles. He called them lords proprietors (ruling landlords). Carolina soon attracted English settlers, French Protestants called Huguenots, and Americans from other colonies. In 1712, the northern two-thirds of the region was divided into two colonies, North Carolina and South Carolina. Much of North Carolina consisted of small farms. Many enslaved Africans also labored in the colony on tobacco plantations and in forest industries. In South Carolina, wealthy landowners purchased Black Africans and their descendants to work the large plantations where they grew rice and indigo. Indigo is a plant that produces blue dye for coloring textiles. South Carolina was the only colony that had more Black people than white people.

Few European settlers came to the southern one-third of Carolina until 1733. Then James Oglethorpe, a British social reformer, founded Georgia there. Oglethorpe hoped Georgia would become a colony of small farms. The colony’s charter banned the importation of Africans so that neither slavery nor plantations would develop. But Georgia later changed the law to allow settlers to bring in enslaved people, and plantations flourished.

Life in colonial America.

Reports of the economic success and religious and political freedom of the early colonists attracted a steady flow of settlers. Through immigration and natural increase, as well as the slave trade from Africa, the colonial population rose to 11/3 million. The colonies drew newcomers from almost every country of western Europe. Despite the varied backgrounds of the early settlers, the white Americans of the mid-1700’s had, as one writer said, “melted into a new race of men.” The slave trade brought in so many Africans that, by the 1750’s, Black people made up one-fifth of the population.

Why the colonists came.

A person who came to America faced hardship and danger. But the New World also offered the opportunity for a fresh start. As a result, many people were eager to become colonists. Some Europeans came seeking religious freedom. In addition to Puritans, Catholics, Quakers, and Huguenots, they included Jews and members of German Protestant sects.

Many Europeans became colonists for economic reasons. Some were well-to-do but saw America as a place where they could become rich. Many poor Europeans came to America as indentured servants. An indentured servant agreed to work for another person, called a master. In return, the master paid for the servant’s transportation across the Atlantic and provided food, clothing, and shelter. Most agreements between servants and masters lasted from four to seven years, after which the servants were freed.

Others who came to America had no choice in the matter. A few were convicts from overcrowded English jails. Most were Africans captured in intertribal warfare or kidnapped, and then sold to European traders. The convicts and enslaved people were sold into service in America.

At first, enslaved Black people had the same legal status as white indentured servants. But by about 1660, colonies began to enact laws that became known as slave codes, which stripped the Africans of basic human rights. All the American Colonies had enslaved people, but slavery became more common in the South than in the North. The South had plantations that required enormous labor, and their owners found it profitable to buy enslaved people to do the work. By the 1750’s, enslaved African Americans accounted for 2 percent of the population in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania, 40 percent in Virginia, and 60 percent in South Carolina.

Economic and social opportunity.

The earliest colonists struggled to produce enough food to stay alive. But before long, America had a thriving economy. Planters and the people they enslaved grew large crops of tobacco, rice, and indigo. Small farmers raised livestock and such crops as wheat and corn. Many colonists fished and hunted. Some cut lumber from forests to make barrels, ships, and other products. The colonists used part of what they produced, but they exported large quantities of goods. They traded chiefly with Britain and the British colonies of the British West Indies. The colonies exported tobacco, wheat, lumber, fish, rice, and indigo. They imported manufactured goods, especially clothing, furniture, and metal utensils from Britain. Their other major imports were sugar, tea, and African captives. The colonies traded with the French, Dutch, and Spanish as well.

Colonial America, like Europe, had both wealthy upper-class and poor lower-class people. But in Europe, traditions designed to keep wealth concentrated among the upper classes made it difficult for anyone to achieve economic and social advancement. America had few such traditions. New waves of immigrants arrived all the time, and advancement was possible for most people. Land became more plentiful and easy to obtain as settlers took more of it from Indigenous groups. There were also many opportunities to start businesses. Many indentured servants acquired land or worked in a trade after their period of service ended. Some former servants or their sons became well-to-do merchants or landowners.

The colonies had a great need for professional people, such as lawyers, doctors, schoolteachers, and members of the clergy. Women were excluded from these careers and many other jobs. However, the professions were open to most white men because they required less specialized training than they do today.

Colonial government.

The colonists lived under British rule. Voters elected their own colonial legislatures, but the British king appointed governors and other top officials in most colonies. The British also passed many laws to regulate trade in ways that helped Britain and only sometimes helped the colonies. But the colonists often ignored British laws they disliked. The British found it hard to enforce laws across the Atlantic Ocean. The tightening of British control over the colonists after they had grown self-reliant led to a clash between the Americans and the British in the late 1700’s. For more information on life in the American Colonies, see Colonial life in America.

The movement for independence (1754-1783)

Relations between the American Colonies and Britain began to break down during the 1760’s. Suddenly, Britain tried to tighten its control over the colonies. Its leaders passed laws that taxed the colonists and restricted their freedoms. The colonists had become accustomed to governing themselves. As a result, they resented what they saw as British interference in their internal affairs. Friction between the Americans and British mounted until, in 1775, the Revolutionary War broke out. During the war—on July 4, 1776—the colonists declared their independence. In 1783, they defeated the British and made their claim to independence stick.

The French and Indian War.

Britain and France had struggled for control of eastern North America throughout the colonial period. As their settlements moved inland, both nations claimed the vast territory between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River. This struggle led to the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which the British won. Under the Treaty of Paris of 1763, Britain gained control of (1) almost all French territory in what is now Canada and (2) all French territory east of the Mississippi except New Orleans. Britain also received Florida from Spain in 1763. As a result, the British controlled almost all of North America from the Atlantic to the Mississippi.

The French and Indian War was a turning point in American history. It triggered a series of British policy changes that eventually led to the movement for colonial independence. See French and Indian wars (The French and Indian War).

Policy changes.

The French and Indian War created problems for Britain. It led to a huge Native American uprising in America in 1763, as colonists moved west into the territory Britain won from France. The uprising became known as Pontiac’s Rebellion, or Pontiac’s War. Also, Britain spent so much money fighting the French and Indian War that its national debt had nearly doubled. George III, who had become king in 1760, instructed Parliament to solve these problems. Parliament began passing laws that taxed the American colonists, restricted their freedom, or both.

In 1763, Parliament voted to station a standing army in North America to defend the colonists against the Indigenous people. Two years later, in the Quartering Act, it required the colonists to help pay for this army by providing the troops with living quarters and supplies. Britain also sought to keep peace with the Native Americans. In the Proclamation of 1763, it prohibited American colonists from settling west of the Appalachians, thus reserving that land for Native American peoples.

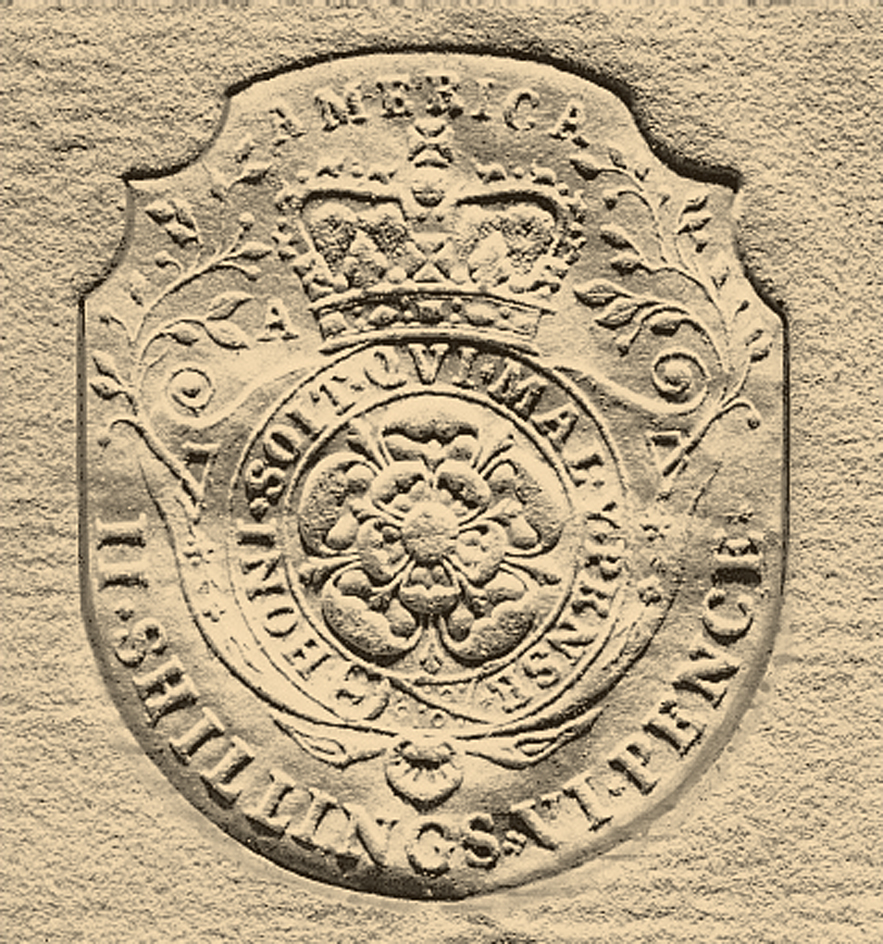

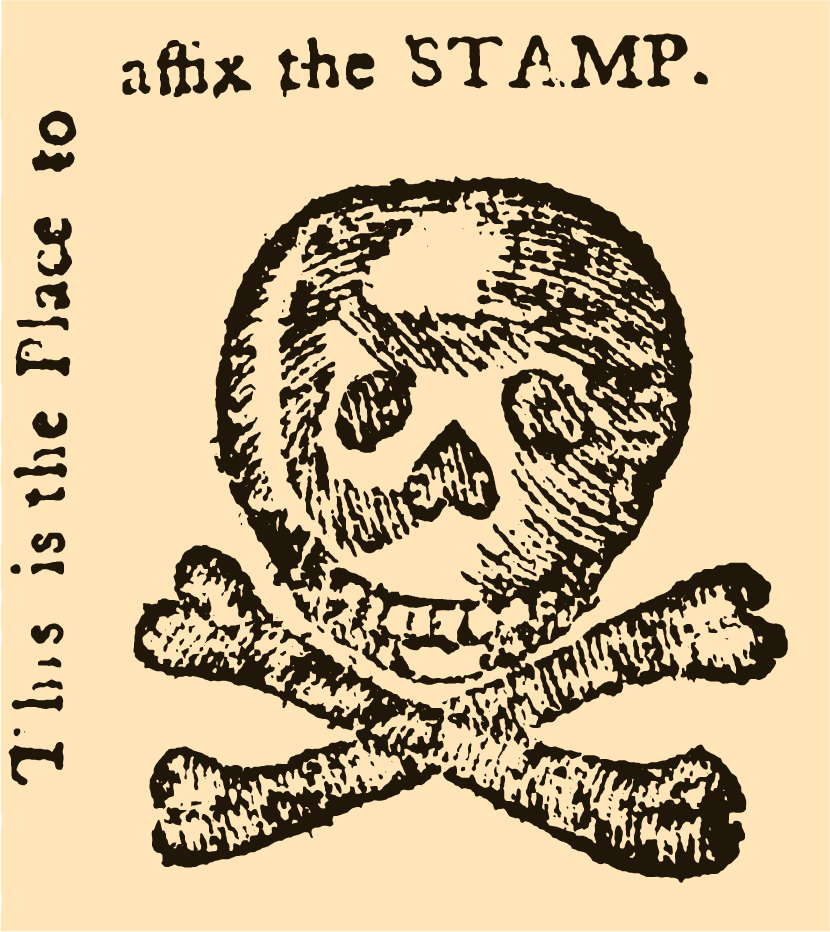

King George and Parliament believed the time had come for the colonists to start obeying trade regulations and paying their share of the cost of maintaining the British Empire. For that reason, in 1764, Parliament passed the Sugar Act. This law provided for the collection of taxes on molasses brought into the colonies. The Sugar Act also gave British officials the right to search the property of people suspected of violating the law. The Stamp Act of 1765 extended to the colonies the traditional English tax on newspapers, legal documents, and various other written materials (see Stamp Act).

Colonial reaction.

The colonists opposed the new British policies. They claimed that the British government had no right to restrict their settlement or deny their freedom in any other way. They also opposed British taxes. The colonists were not represented in Parliament. Therefore, they argued, Britain had no right to tax them. The colonists expressed this belief in the slogan, “Taxation Without Representation Is Tyranny.”

To protest the new laws, colonists organized a boycott of British goods. Men joined secret clubs called Sons of Liberty that used threats of violence to prevent enforcement of the laws (see Sons of Liberty). Women made items for themselves and their families to avoid purchasing British goods. For example, they created and wore homespun garments instead of clothing imported from Britain. In 1765, representatives of nine colonies met in the Stamp Act Congress to consider joint action against Britain. The colonial boycott and other acts of resistance were successful. In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act. But at the same time, in the Declaratory Act, it insisted that Britain had the right to make laws for the colonies.

Renewed conflict.

The repeal of the Stamp Act eased tensions between the Americans and the British only briefly. In 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which taxed lead, paint, paper, and tea imported into the colonies. Colonists responded with renewed protests and another boycott of British goods.

As tensions between the Americans and British grew, Britain sent troops into Boston and New York City. The sight of British troops in their streets aroused the colonists’ anger. On March 5, 1770, a crowd of Boston civilians taunted and attacked a small group of soldiers. The troops fired on the civilians, killing three people and wounding eight others, two of whom died later. This incident, the Boston Massacre, shocked Americans and disturbed the British. See Boston Massacre.

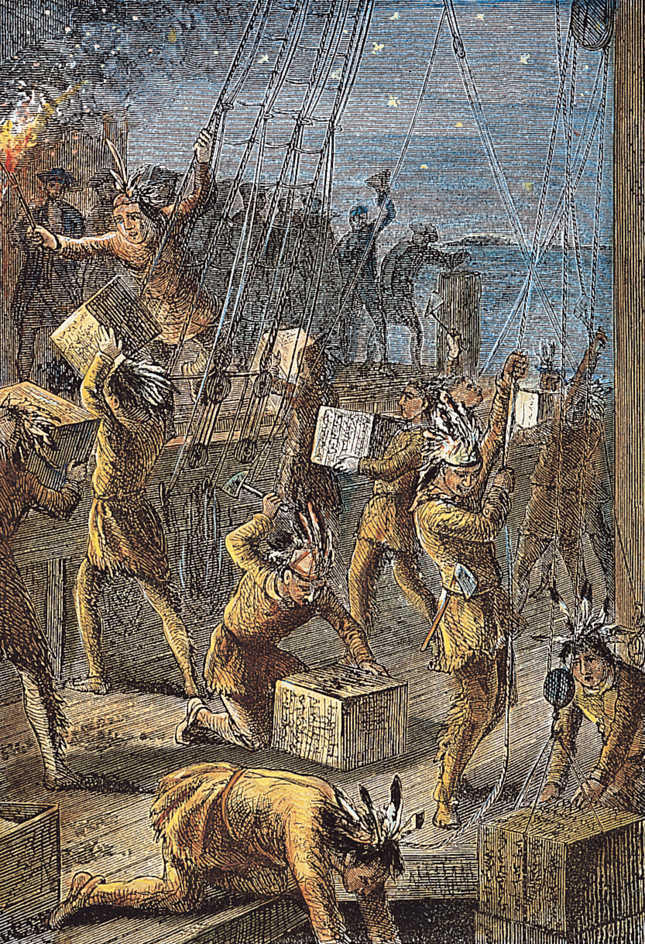

In 1770, Parliament repealed all provisions of the Townshend Acts except one, the tax on tea. Three years later, in the Tea Act, Parliament reduced the tax on tea sold by the East India Company, a British firm, and gave the company’s agents a monopoly on local tea sales in the colonies. The colonists saw these actions as taxing them and hurting American shopkeepers to benefit a big British company. Americans vowed not to drink tea, and mobs frightened the agents who tried to sell it. On Dec. 16, 1773, a group of colonists dramatized their opposition in the Boston Tea Party. Dressed as Native Americans, they boarded the East India Company’s ships and threw its tea into Boston Harbor. See Boston Tea Party.

Angered by the Boston Tea Party, Parliament passed laws in 1774 to punish the colonists. Britain called these laws the Coercive Acts. Americans called them the Intolerable Acts. The laws included provisions that closed the port of Boston, suspended democratic government in Massachusetts, and required the colonists to house and feed British soldiers.

The First Continental Congress.

The Coercive Acts stirred colonial anger more than ever. On Sept. 5, 1774, delegates from 12 colonies met in the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. The delegates were cautious men who disliked lawlessness and still hoped for a settlement with the British government. They reaffirmed American loyalty to Britain and agreed that Parliament could direct colonial foreign affairs. However, the delegates called for a boycott of all trade with Britain until Parliament repealed certain laws and taxes, especially the Coercive Acts. King George shattered hope for reconciliation by insisting that the colonies submit to British rule or be crushed. See Continental Congress.

The American Revolution begins.

On April 19, 1775, British troops tried to seize the military supplies of the Massachusetts militia. This action led to the start of the Revolutionary War. Colonists—first at Lexington, and then at Concord, Massachusetts—took up arms and inflicted numerous casualties on the British. Word of their success spread, and hope grew for victory over Britain. Colonial leaders met in the Second Continental Congress on May 10, 1775, to prepare for war. The Congress organized the Continental Army and, on June 15, chose George Washington of Virginia as its commander in chief.

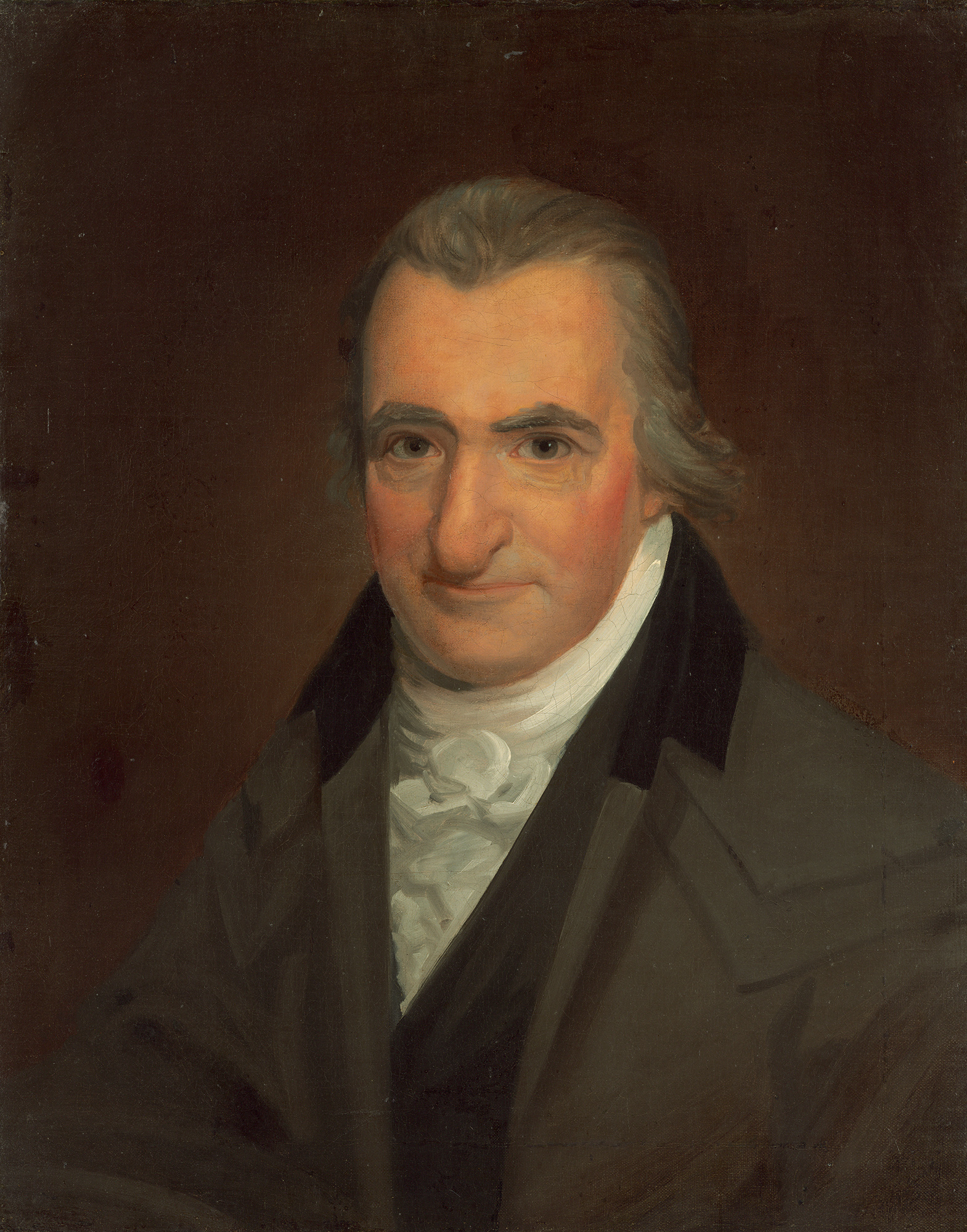

King George officially declared the colonies in rebellion on Aug. 23, 1775. He warned the Americans to end their rebellion or face certain defeat. But the threat had little effect on the colonists’ determination. Some Americans, called Loyalists, remained true to Britain, but a growing number of Americans supported the fight for independence. Many who had been unsure were convinced by Thomas Paine’s pamphlet Common Sense (1776). Paine called for complete independence from Britain and the creation of a strong federal union.

The Declaration of Independence.

On July 4, 1776, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence and formed the United States of America. Drafted by Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, the Declaration was a sweeping indictment of King George and the British Parliament. It also set forth certain principles that were basic to the revolutionary cause. It says all men are created equal and are endowed by their Creator with inalienable rights—that is, rights which cannot be taken away—to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Governments exist to protect those rights and derive their powers from the consent of the governed. The Declaration also says that when a government ceases to preserve those rights, it is the people’s duty to change the government, or abolish it and form a new one.

American victory.

In the Revolutionary War, the Americans faced the world’s most powerful empire. They lacked a well-trained army, a navy, military supplies, and money. But they had the advantage of fighting on their home territory. The British, on the other hand, had well-trained and well-equipped troops and officers, a powerful navy, and Native American allies who wanted to prevent Americans from taking more of their lands. But the British were fighting far from home.

Foreign aid helped the American cause. France and other European nations who opposed Britain loaned money to the United States. In 1777, France entered the war on the American side. Its army and navy ultimately helped the United States win the war.

The Revolutionary War raged on through the 1770’s. Then, on Oct. 19, 1781, American and French troops won a decisive victory at the Battle of Yorktown in Virginia. Thousands of British soldiers surrendered. Within months, the British government decided to seek peace. Two years of peace negotiations and occasional fighting followed. Finally, on Sept. 3, 1783, the Americans and the British signed the Treaty of Paris. The treaty officially ended the Revolutionary War, with British recognition of American independence. For a detailed account of the war, see American Revolution.

Forming a new nation (1784-1819)

As a result of the Treaty of Paris of 1783, the new nation controlled all of North America from the Atlantic to the Mississippi between Canada and Florida. Canada remained British territory. Britain returned Florida to Spain, and Spain continued to control the area west of the Mississippi. The original Thirteen Colonies made up the first 13 states of the United States, which was only a loose confederation of states at first.

Establishing a government.

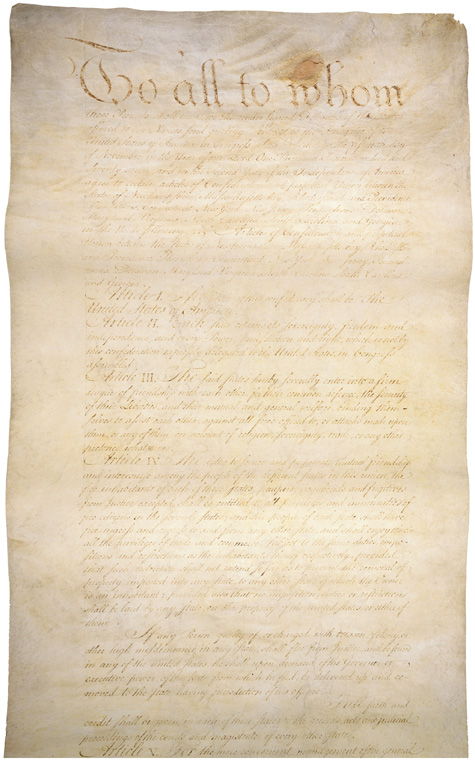

Americans began setting up a new system of government as soon as they declared their independence. Each of the new states had its own constitution before the Revolutionary War ended. The constitutions gave the people certain liberties, usually including freedom of speech, religion, and the press. In 1777, the Second Continental Congress designed a weak federal government under the Articles of Confederation. By the time the states finished ratifying the Articles in 1781, some Americans already thought the nation needed a stronger federal government.

The Articles of Confederation.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the federal government consisted of Congress. There was no president or federal court system. Congress organized the Revolutionary War effort and managed foreign diplomacy. But the Articles did not allow Congress to collect taxes, regulate foreign trade, or direct the activities of the states.

Under the Articles, each state worked independently for its own ends. Congress could make recommendations but could not enforce them. Yet the new nation faced problems that demanded a strong federal government. The United States had piled up a huge debt during the Revolutionary War. Because Congress could not collect taxes, the nation could not pay the interest on this debt to achieve a sound financial footing. Congress could not even pay the salaries of the Continental Army. It had no power to regulate the nation’s trade.

Some states issued their own paper money, causing sharp changes in the value of currency and economic chaos. In 1786 and 1787, this chaos led to Shays’s Rebellion in Massachusetts. Rebels led by Daniel Shays, a former army officer, shut down the state courts to stop them from hearing debt cases. Shays’s Rebellion scared many Americans and dramatized the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation. See Articles of Confederation; Shays’s Rebellion.

Writing the Constitution.

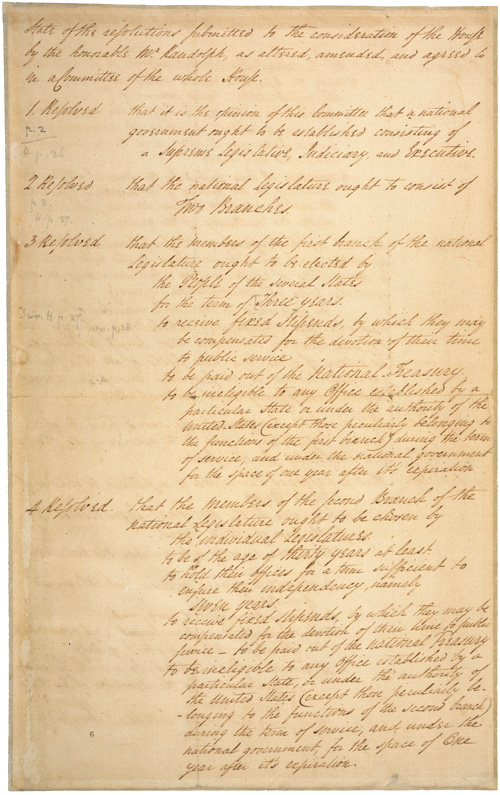

In 1787, delegates from every state except Rhode Island met in Philadelphia’s Independence Hall to consider amendments to the Articles of Confederation. Rhode Island did not take part because its leaders worried about outside interference in the state’s affairs. The convention decided not to draft amendments to the Articles. Instead, the delegates wrote an entirely new Constitution for the United States.

The delegates debated long and hard over the provisions of the Constitution. Some of them wanted a document that gave much power to the federal government. Others wanted to protect the power of the states and called for a weak central government. Delegates from large states said their states should have greater representation in Congress than the small states. But small-state delegates demanded equal representation in Congress. Delegates from the Southern States insisted that enslaved Black people be counted in determining the representation of each state in Congress. Northern delegates answered that because enslaved people could not vote, counting them would give white Southerners an unfair advantage.

The delegates finally reached an agreement on a new Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787. The authors worked out a system of government that satisfied the opposing views of the delegates to the convention. At the same time, they created a system that was flexible enough to continue in its basic form to the present day.

The men who wrote the Constitution included some of the most famous and important figures in American history. Among them were George Washington and James Madison of Virginia, Alexander Hamilton of New York, and Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania. The authors of the Constitution, along with such other early leaders as Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, won lasting fame as the Founding Fathers of the United States.

Provisions of the Constitution.

The Constitution established a two-house legislature, consisting of a House of Representatives and a Senate. In the House, representation was based on population to satisfy the large states. In the Senate, each state had two seats, regardless of its size, which pleased the small states. In a compromise between the Northern and Southern states, the Constitution provided that the population count for the House of Representatives would include all free people plus three-fifths of the enslaved Black population. The three-fifths clause caused resentment in the North because it gave the South extra power in Congress.

The Constitution also created the office of president of the United States. The president was elected by an Electoral College, a group of men chosen by the states (see Electoral College). Each state had a number of electors equal to its number of members in the House of Representatives plus its two senators. Because the House was based on the three-fifths clause and no enslaved people could vote, the Electoral College effectively granted white Southerners extra votes in presidential elections.

The Constitution gave many powers to the federal government, including the power to collect taxes and regulate trade. But the document also reserved certain powers for the states. The Constitution provided for three branches of the federal government: (1) the executive, headed by the president; (2) the legislative, made up of the two houses of Congress; and (3) the judicial, consisting of the federal courts. The authors of the Constitution created a system of checks and balances among the three branches of government. Each branch received specified powers and duties to ensure that the other branches did not have too much power.

Adopting the Constitution.

Before the Constitution became law, it needed ratification (approval) by nine states. Some Americans opposed the Constitution, and a fierce debate broke out. Hamilton, Madison, and John Jay responded to criticism of the document in a series of 85 newspaper essays published in 1787 and 1788. Called The Federalist, the essays gained much support for the Constitution (see Federalist, The). On June 21, 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify.

The Bill of Rights.

Much opposition to the Constitution stemmed from fears that it did not guarantee enough individual rights. In response, 10 amendments called the Bill of Rights were added. The Bill of Rights became part of the Constitution on Dec. 15, 1791. Among other things, it guaranteed freedom of speech, religion, and the press; and the rights to trial by jury and peaceful assembly. For more details, see Constitution of the United States; Bill of rights.

Setting up the government.

In 1789, the Electoral College unanimously chose George Washington to serve as the first president. It reelected him unanimously in 1792. Local voters elected members of the House of Representatives, as they do today. But state legislatures chose the members of the Senate, a practice that continued until the early 1900’s. The government went into operation in 1789, with its temporary capital in New York City. The capital moved to Philadelphia in 1790, and to Washington, D.C., in 1800. Loading the player...

Washington, the first President of the United States of America

Financial problems

plagued the new government. The national debt piled up during the Revolutionary War threatened the financial health of the United States. Americans split over how to deal with the financial problems. One group, led by Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, wanted the federal government to take vigorous action to pay off the debt and foster economic growth. Another group, headed by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, wanted the government to proceed more cautiously on the debt and opposed government participation in economic affairs.

Hamilton proposed that the federal government increase tariffs (taxes on imports) and that it tax certain products made in the United States, such as liquor. The government would use the money to pay its own debts and those of the states. The government would also use the funds for ongoing expenses and internal improvements, such as roads and bridges. Hamilton proposed a national bank, an agency that would be authorized to issue currency and perform other financial services for the federal government.

Jefferson and his followers, who included many Southerners, denounced Hamilton’s plans. But Jefferson later agreed to support some of Hamilton’s proposals. In return, Hamilton agreed to support a shift of the national capital to the South. Congress approved the financial plan and moved the capital to Washington, D.C. Jefferson continued to oppose the bank proposal. But in 1791, Congress chartered a national bank to handle the government’s finances for 20 years (see Bank of the United States).

The new tax program led to an uprising called the Whiskey Rebellion. In 1794, farmers in Pennsylvania who made whiskey refused to pay the liquor tax. President Washington sent in troops who ended the rebellion. Washington’s action did much to establish the federal government’s authority to enforce its laws within the states. See Whiskey Rebellion.

Problems in foreign affairs.

The new government faced serious problems in foreign affairs. In 1793, France went to war against Britain and Spain. Americans were grateful to France for its help in the American Revolution, but they also wanted to reestablish trade with Britain and its colonies in the British West Indies. Americans disagreed over which side to support. Jefferson and his followers wanted to back France. Hamilton and his group favored Britain.

President Washington insisted that the United States remain neutral in the European war. He rejected French demands for support, and he also sent diplomats to Britain and Spain to clear up problems with those countries. Chief Justice John Jay, acting for Washington, negotiated the Jay Treaty with Britain in 1794. The treaty included a trade agreement and a British promise to remove troops still stationed on U.S. territory. In 1795, Thomas Pinckney negotiated the Pinckney Treaty, or Treaty of San Lorenzo, with Spain. This treaty settled a dispute with Spain over the Florida border. Spain also granted the United States free use of the Mississippi River. See Jay Treaty; Pinckney Treaty.

In 1796, Washington refused to seek a third term as president, in part because he thought staying too long would make him resemble a king. John Adams of Massachusetts succeeded Washington in 1797. At about that time, French warships began attacking U.S. merchant vessels. Adams, like Washington, hoped to use diplomacy to solve foreign problems. He sent diplomats to France to try to end the attacks. But three agents of the French government insulted the diplomats by demanding a bribe. The identity of the agents was not revealed. They were called X, Y, and Z, and the incident became known as the XYZ Affair. Reports of the French action created uproar in the United States. But Adams was determined to keep peace. In 1799, he again sent diplomats to France. This time, the United States and France reached a peaceful settlement. See XYZ Affair.

Establishing political parties.

Washington and many other American leaders opposed political parties, believing that they caused disagreement and ill will. But in the 1790’s, the disputes over government policies led to the establishment of two parties. Hamilton and his followers, chiefly Northerners, formed the Federalist Party. The Federalist Party favored a strong federal government and generally backed Britain in international disputes. Jefferson and his followers, chiefly Southerners, created the Democratic-Republican Party, also known as the Republican Party. It had no relation to today’s Republican Party. The Democratic-Republicans wanted a weak central government and generally sided with France in foreign disputes. See Federalist Party; Democratic-Republican Party.

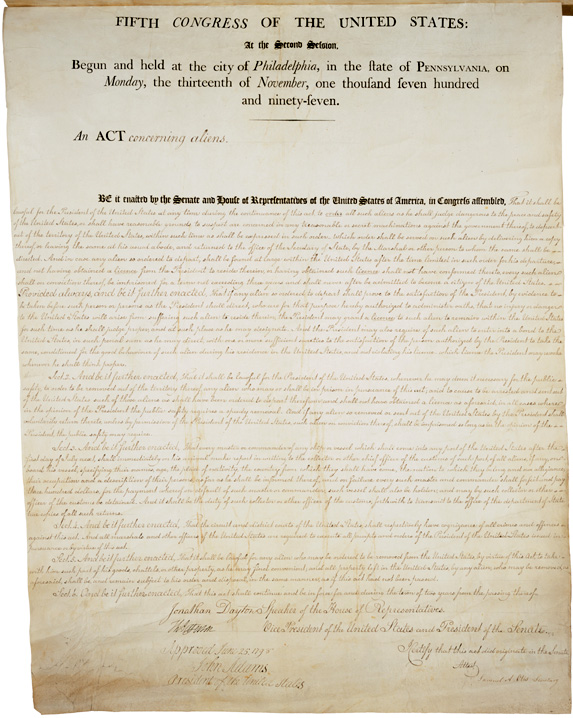

The Alien and Sedition Acts.

It took a while for Americans to accept the idea that taking strong political positions was a normal part of democratic politics. The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans could not believe their opponents had the country’s best interests at heart. After the XYZ Affair, for example, the Federalist Party denounced the Democratic-Republicans for their support of France. The Federalists had a majority in Congress. They set out to silence their critics, including Democratic-Republicans and foreigners living in the United States. In 1798, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, with the approval of President Adams, who was also a Federalist. These laws made it a crime for anyone to criticize the president or Congress, and subjected foreigners to unequal treatment.

These attacks on freedom caused a nationwide outcry. The protests included the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions. The resolutions were statements by the Kentucky and Virginia state legislatures that challenged the constitutionality of the Alien and Sedition Acts. The most offensive parts soon expired or were repealed. But the Alien and Sedition Acts gave the Federalists the reputation as a party that restricted freedom. See Alien and Sedition Acts; Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions.

The Jeffersonian triumph.

Public reaction to the Alien and Sedition Acts helped Jefferson defeat John Adams to win election as president in 1800. Supporters of Jefferson called his election a triumph for his political philosophy, which became known as Jeffersonian democracy. Jefferson envisioned the United States as a nation of small farmers. In his ideal society, the people would lead simple but productive lives and direct their own affairs. As a result, the need for government would decline. Jefferson hoped that slavery would eventually die out but doubted that the government could do anything to restrict it. Despite his views, Jefferson took actions as president that expanded both slavery and the role of the government.

The Louisiana Purchase,

the first major action of Jefferson’s presidency, almost doubled the size of the United States. It also led, ultimately, to the westward expansion of slavery. In 1801, Jefferson learned that France had taken over from Spain a large area between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains called Louisiana. After France failed to crush a revolution by enslaved people in Haiti, the French ruler, Napoleon I, abandoned his plans to exert influence in the Western Hemisphere. He decided to sell Louisiana to the United States. Jefferson arranged to buy it for about $15 million in 1803. The Constitution did not authorize the government to buy foreign territory. Jefferson agreed that he had created a new power.

The Louisiana Purchase added 827,987 square miles (2,144,476 square kilometers) of territory to the United States. The first states to be carved out of the Louisiana Purchase were Louisiana (1812), Missouri (1821), and Arkansas (1836). All three were slave states.

The power of the federal government

increased during Jefferson’s presidency as a result of rulings by the Supreme Court. John Marshall had become chief justice of the United States in 1801. Under Marshall, the court became a leading force in American society. In 1803, in the case of Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court asserted its right to rule on the constitutionality of federal laws (see Marbury v. Madison). From then to Marshall’s death in 1835, the court reviewed about 50 cases that involved constitutional issues.

Marshall’s court expanded the power of the federal government. For example, in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), it ruled that Congress has implied powers in addition to the powers specified in the Constitution. The Supreme Court also said that federal authority prevails over state authority when the two come into conflict (see McCulloch v. Maryland).

Jefferson’s foreign policy.

In 1803, Britain, by then known as the United Kingdom, went to war again with France. Both nations began seizing U.S. merchant ships. The British also captured American seamen and forced them into the British Navy. Jefferson again expanded the government’s powers, this time to protect U.S. shipping. At his request, Congress passed laws designed to end British and French interference. The Embargo Act of 1807 made it illegal for American goods to be exported to foreign countries. The embargo threatened to ruin the nation’s economy, and the law was repealed in 1809. The Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 prohibited Americans from trading with the United Kingdom or France. But the warring nations still interfered with U.S. trade.

The War of 1812.

James Madison succeeded Jefferson as president in 1809. France soon promised to end its interference with U.S. shipping, but the United Kingdom did not. Also, in the Ohio River Valley, the Shawnee chief Tecumseh helped unite Native American tribes to try to stop westward expansion by white settlers. Americans believed the British were supplying the Native Americans. For these reasons, many Americans demanded war against the United Kingdom. They were led by members of Congress from the West and South called War Hawks. The War Hawks included Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Other Americans, especially New Englanders, opposed the War Hawks’ demand. But on June 18, 1812, at Madison’s request, Congress declared war on the United Kingdom, and the War of 1812 began.

The two sides struggled to gain an advantage in the war. The United Kingdom was busy fighting the French in Europe, and the United States was poorly prepared for war. American forces killed Tecumseh in a battle in Canada in 1813 and won a naval victory on Lake Erie near Detroit, but the Americans also suffered major setbacks. On Aug. 24, 1814, the British captured Washington, D.C., and burned the White House and other government buildings. Eventually, American troops drove back the British.

Neither side won the War of 1812. The Treaty of Ghent, signed in 1814 and ratified (approved) in 1815, ended the war. See War of 1812.

Decline of the Federalists.

In 1814 and early 1815, New England Federalist leaders who opposed the War of 1812 held a meeting called the Hartford Convention. They were angry about the war and Southern domination of the federal government. They demanded seven amendments to the Constitution, including one removing the three-fifths clause and another making it harder for Congress to declare war. Opponents charged that they threatened the secession (withdrawal) of the New England States from the Union. The Federalists never recovered from this charge or their opposition to the War of 1812. Democratic-Republicans called them disloyal, and the Federalist Party broke up as a national organization after 1816. The breakup left no party to oppose the Democratic-Republicans. The Democratic-Republican candidate for president in 1820, James Monroe of Virginia, ran unopposed. See Hartford Convention.

The Era of Good Feeling.

A spirit of nationalism swept through the nation following the War of 1812. The war increased feelings of self-confidence. The defeat of Tecumseh made it easier for settlers to move west. Peace in Europe led to expanded trade and allowed Americans to concentrate on their own affairs. The nation acquired new territory, and new states entered the Union. The economy prospered. Historians sometimes call the period from 1815 to the early 1820’s the Era of Good Feeling because of its relative peace, unity, and optimism about the future.

The American System.

After the War of 1812, Henry Clay and other nationalists said the government should actively foster the economy’s growth. They proposed a set of measures called the American System. They said the government should raise tariffs to protect American manufacturers from foreign competition so that industries would grow and employ more people. The government should spend the tariff revenues on transportation projects and other internal improvements to help farmers ship their crops to market and knit the country together. A national bank should regulate the nation’s currency and take care of the government’s finances.

Congress soon put the American System into practice. In 1816, it enacted a high tariff and chartered the second Bank of the United States. The federal government also increased its funding of internal improvement projects, the most important of which was the National Road. Begun in 1811, the road stretched from Maryland to Illinois when completed. It became an important route for the shipment of goods and the movement of settlers westward.

Other transportation improvements included the development of the steamboat. In 1807, the American inventor Robert Fulton demonstrated the first commercially successful steamboat, the Clermont. The steamboat soon became the fastest way to ship goods and carry passengers by river.

The state governments as well as the federal government financed transportation improvements. The states built many canals to connect natural waterways. The Erie Canal, the most important, was built by New York state. Completed in 1825, it connected Albany, on the Hudson River, to Buffalo, on Lake Erie. It led to the growth of farms and towns across New York. By establishing a water route from New York City to the Great Lakes, the Erie Canal made it profitable for settlers to start farms in the Midwest. Canal boats carried manufactured goods from east to west and farm produce from west to east. See Erie Canal.

A national culture.

Americans had patterned their culture largely after European civilization. Architects, painters, and writers tended to imitate European models. In the early 1800’s, however, the writer Ralph Waldo Emerson and other thinkers called for an art and culture based on uniquely American experiences. Architects began to design simple houses that blended into their surroundings. Craftworkers built sturdy furniture that was suited to frontier life, yet elegantly simple. The nation’s literature also flourished when it began to reflect American experiences. The writings of Washington Irving, a leading early author, helped gain respect for American literature.

Cotton and slavery.

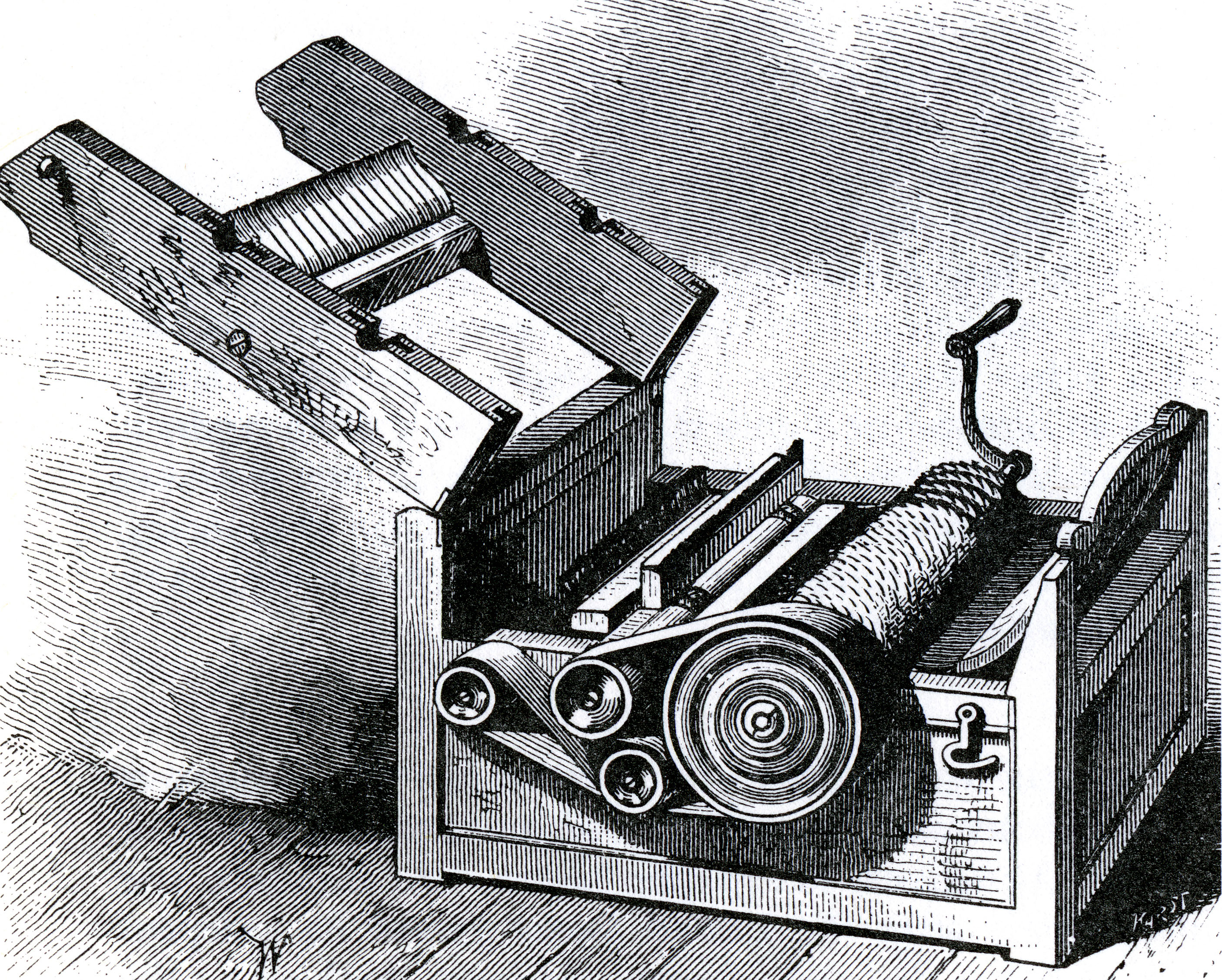

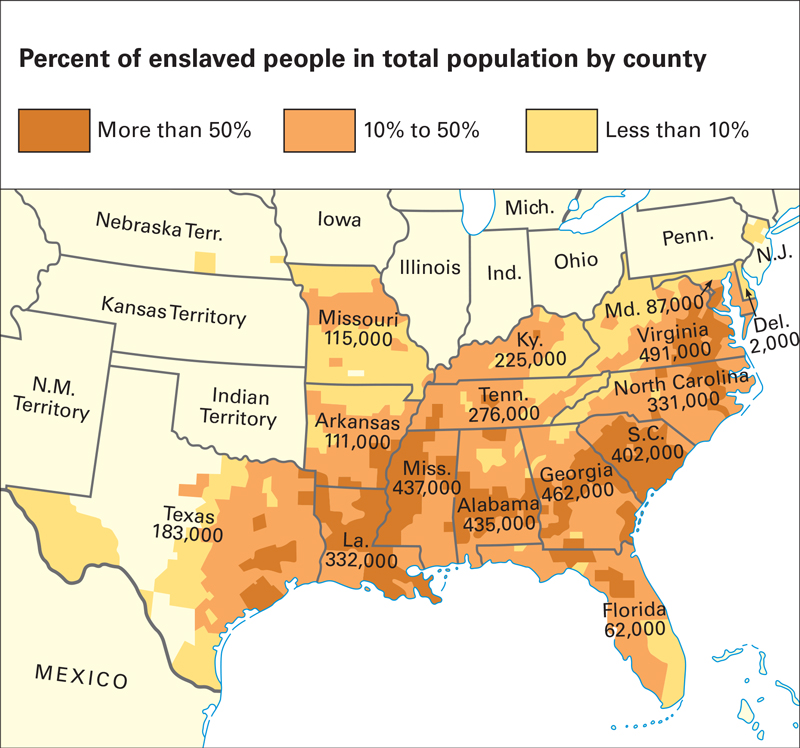

In the 1700’s, the main crops in the South were tobacco and rice. In the 1800’s, however, cotton became the region’s leading crop. In 1793, the American inventor Eli Whitney devised the cotton gin, a machine that separated cotton fiber from the seeds as fast as 50 people could by hand. This machine helped cause a boom in cotton production across the South (see Cotton gin). Cotton planters, who used enslaved African Americans to work their fields, poured into the new states of Louisiana, Alabama, and Mississippi. In 1819, the United States acquired Florida in a treaty with Spain, and cotton growers also went there. New Orleans, Louisiana, prospered as the nation’s leading slave market. Slaveholders farther east in Virginia, Maryland, and other states sold hundreds of thousands of enslaved people into what was soon known as the Cotton Kingdom. Slave traders and owners often separated African American families by selling children, parents, and other relatives away from each other.

The Missouri crisis.

The Era of Good Feeling did not mean an end to all the country’s political disputes. The westward expansion of slavery caused a bitter fight between Northerners and Southerners in Congress from 1819 to 1821. By 1819, every Northern state had outlawed slavery. But the plantation system had spread throughout the South, and the economy of the Southern States depended on the labor of enslaved people. The question of whether to encourage or limit the westward expansion of slavery became a hotly disputed political issue. Through the years, the United States had kept a balance between the number of free states, where slavery was prohibited, and slave states, where it was allowed. This balance meant that both sides had the same number of members in the U.S. Senate. By 1819, there were 11 free states and 11 slave states.

When the Territory of Missouri applied for admission to the Union as a slave state, most Northern members of Congress insisted that it enter as a free state instead. Either way, the balance in the Senate between free and slave states would be upset. After almost two years of angry debates, Congress worked out the Missouri Compromise, which temporarily maintained the balance. Massachusetts agreed to give up the northern part of its territory. This area became the state of Maine, and entered the Union as a free state in 1820. In 1821, Missouri entered as a slave state, and so there were 12 free and 12 slave states.

The Missouri Compromise also had another important provision. It provided that slavery would be “forever prohibited” in all territory gained from the Louisiana Purchase that was north of Missouri’s southern border, except for Missouri itself. See Missouri Compromise.

Expansion (1820-1849)

From the 1820’s to the 1850’s, the United States grew greatly in land, population, and wealth. Thousands of settlers moved westward into new states and territories. Immigration from Europe brought hundreds of thousands of newcomers. British, Irish, German, and Scandinavian immigrants settled in Eastern cities and across the West. In the 1850’s, Chinese immigrants also began to arrive on the West Coast. The federal government made more land available to white settlers through the policy of removal, in which the U.S. Army forced Native Americans to leave their lands in both Eastern and Western states. In the South, the cotton industry grew so rapidly that cotton accounted for half the value of all U.S. exports. Meanwhile, in the Northeast, the nation’s first large factories appeared. Some of the factory workers were women and children, and many were immigrants.

The United States moves west.

By 1820, Americans had established settlements as far west as the Mississippi River. By the 1830’s, they had pushed the frontier across the river, into Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and eastern Texas. The land beyond, called the Great Plains, was dry and treeless, and it seemed to be poor farmland. But explorers, traders, and others who had journeyed farther west told of rich land and forests beyond the Rocky Mountains. In the 1840’s, large numbers of settlers made the long journey across the Great Plains to the Far West.

The Western settlers included Easterners from both the North and South. Many other settlers came from Europe. Some people went west in search of religious freedom. The best known of these were the Mormons, who settled in Utah in 1847. Enslaved African Americans often went west against their will.

Most of the settlers became farmers who owned their own plots. But urban life also moved westward with the frontier. Bustling towns and cities grew up in the West. There, traders in farm equipment and other supplies carried on a brisk business. The towns had banks, churches, hotels, and stores. The townspeople included craftworkers, doctors, lawyers, government officials, schoolteachers, and members of the clergy.

Westward expansion of the United States gave rise to changes in American politics. It revived conflict over slavery because Congress had to decide whether to allow slavery into new states and territories. Western settlers joined up with Easterners who wanted the government to improve the country’s transportation system with new roads, canals, and railroads. For more details, see Westward movement in America.

The Monroe Doctrine.

The United States maintained peaceful relations with Europe during the era of expansion. But as Mexico and the nations of Central and South America won independence from Spain in the 1820’s, Americans worried that Europeans might interfere. In 1823, President Monroe issued the Monroe Doctrine, a statement warning European countries not to interfere with the nations in the Western Hemisphere (see Monroe Doctrine).

Manifest destiny.

Some settlers moved beyond the western boundary of United States territory. They flocked to Texas, California, and other lands belonging to Mexico. Americans also settled in the Oregon Country, a large territory between California and Alaska claimed by both the United Kingdom and the United States. By then, many Americans had come to believe that westward expansion was the manifest destiny of the United States—that is, the clear future of the nation. According to the belief of manifest destiny, the United States had the right to take all of North America. For many, manifest destiny justified the idea that white Americans were superior to Native Americans and Mexicans. Stirred by this belief, Americans demanded control of the Oregon Country and much of Mexico.

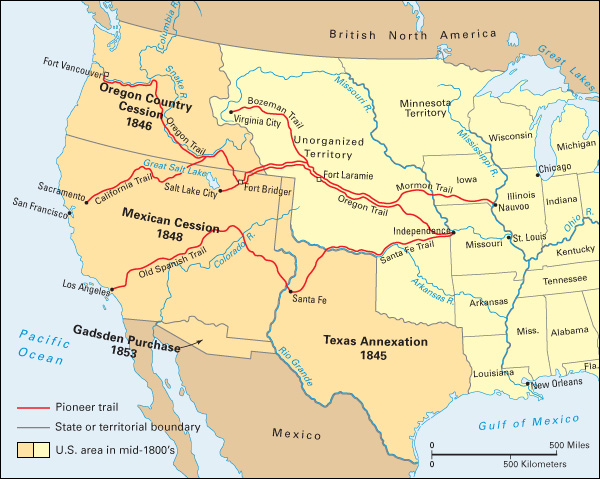

The conflicting claim with the United Kingdom over Oregon was settled fairly easily. The British decided the effort needed to hold on to all of Oregon was not worthwhile. In 1846, they turned over to the United States the part of Oregon south of the 49th parallel, except Vancouver Island. See Oregon Territory.

The struggle over Mexican territory was more complicated. It began in Texas in 1835, when American settlers, who had been invited to settle there by the Mexican government, revolted against Mexican rule. In 1836, these settlers proclaimed Texas an independent republic. Nine years later, the United States annexed Texas and made it a state, despite Mexico’s opposition.

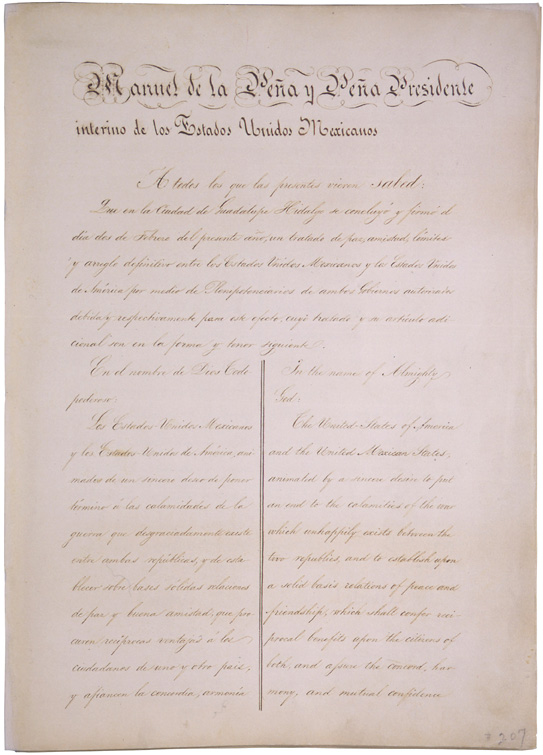

The Mexican War.

The United States gained additional Mexican territory in the Mexican War. In 1846, President James K. Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to occupy land near the Rio Grande that both the United States and Mexico claimed. Fighting broke out between Taylor’s troops and Mexican soldiers. On May 13, 1846, at Polk’s request, Congress declared war on Mexico. The United States quickly defeated its neighbor. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on Feb. 2, 1848, officially ended the war. The treaty gave the United States a vast stretch of land from Texas west to the Pacific and north to Oregon. The nation then extended from coast to coast. See Mexican War.

In 1853, in the Gadsden Purchase, the United States bought from Mexico the strip of land on the southern edge of Arizona and New Mexico. Although many Native Americans disagreed, the United States now claimed to own all the territory of its present states except Alaska (purchased from Russia in 1867) and Hawaii (annexed in 1898). See Gadsden Purchase.

Economic growth.

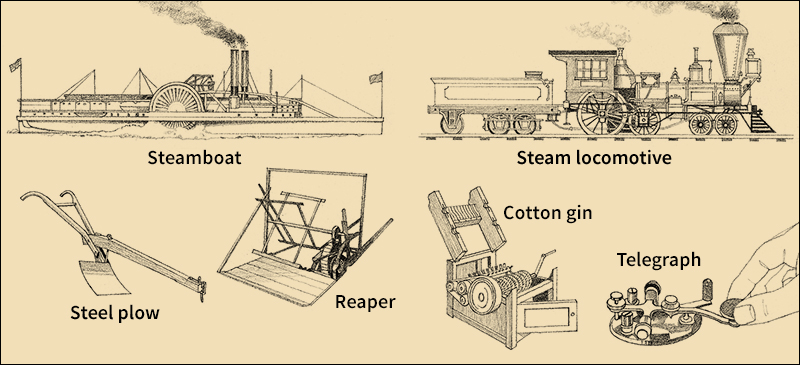

Expansion into the rich interior of the continent enabled the United States to become the world’s leading agricultural nation. Southern cotton was in great demand as a raw material for textile mills in Europe and the northeastern United States. Planters, enslaved workers, and family farmers in the South as far west as Texas raised cotton to supply the mills. Many planters in Kentucky and Tennessee prospered by growing tobacco and hemp, used for making rope. Midwesterners and Westerners produced large crops of corn and wheat, and also raised livestock. New machines boosted the output of U.S. farms. Eli Whitney’s cotton gin had already transformed Southern agriculture. The reaper, patented by the American inventor Cyrus McCormick in 1834, allowed Northern farmers to harvest grain much quicker than before.

The discovery of minerals in the West also boosted the economy. The most famous mineral strike took place in 1848, when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California. See Forty-Niners; Gold rush.

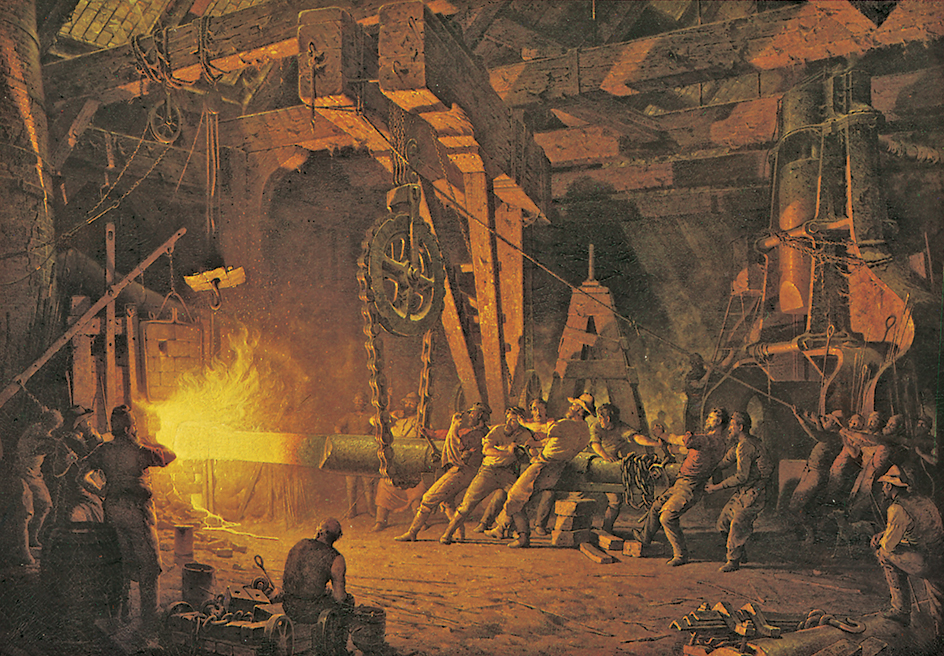

The period also marked the beginning of large-scale manufacturing in the United States. Previously, most manufacturing was done by craftworkers at home or in small shops. But in the early 1800’s, businesses began to erect factories with machinery that enabled them to produce goods more rapidly and cheaply.

Advances in transportation and communications

contributed to the economic growth of the United States. New or improved roads, such as the National Road in the East and the Oregon and Santa Fe trails in the West, eased the difficulty of traveling and shipping goods by land. The increased use of steamboats and the construction of canals improved water transportation. The steam-powered railroad soon rivaled steamboats and canal boats. By 1850, about 9,000 miles (14,500 kilometers) of railroad lines were in operation.

In 1837, the American inventor Samuel F. B. Morse demonstrated the first successful telegraph in the United States. The telegraph gave businesses the fastest means of communication yet known.

The election of 1824

destroyed the one-party rule of the Era of Good Feeling. Four Democratic-Republicans sought to succeed James Monroe as president. Andrew Jackson received the most electoral votes, and John Quincy Adams came in second. But nobody won a majority, and the House of Representatives had to select the new president. The House chose Adams. Embittered, Jackson and his followers formed a separate wing of the Democratic-Republican Party, which soon developed into the Democratic Party.

The rise of Andrew Jackson.

Historians often call the 1830’s and 1840’s the Age of Jackson, after Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, the most influential political leader of the era. Jackson, a rich slaveholder and a general in the War of 1812, was famous for success in battles against Native Americans and the British. He created a new kind of politics in which appeals to the “common man” drew enthusiastic mass support. By the 1820’s, most white men had gained the right to vote, as states abolished requirements that voters own land. Yet most states barred African American men and all women from voting. Even so, high turnouts at elections—up to 80 percent of the men who were eligible to vote—made U.S. politics more democratic than ever before.

Jackson ran for president for a second time in 1828. He appealed for support from Western farmers and Eastern city laborers and craftworkers. His reputation as a war hero and “Indian fighter” made him popular. He promised to end what he called a “monopoly” of government by the rich and to protect the interests of the “common man.” Jackson was elected by wide margins in 1828 and again in 1832.

Jackson as president.

When Jackson became president, he fired many federal officials and gave their jobs to his supporters. He called this policy “rotation in office” and said it was democratic because it allowed more men to hold federal positions. His opponents called it the “spoils system” and said it was corrupt because it distributed federal jobs to reward men for their party loyalty instead of their qualifications.

One of Jackson’s main crusades as president involved the second Bank of the United States. The bank held the government’s deposits and regulated the nation’s money supply by controlling how much currency was issued. Jackson thought that the bank favored the wealthy and that it was unfair for one bank to have a monopoly on holding the government’s money. In 1832, Congress voted to recharter the bank, but Jackson vetoed the bill. He soon withdrew the government’s money from the bank, and the bank later collapsed.

Another great issue of Jackson’s administration involved tariffs and nullification (action by a state to cancel a federal law). In 1828, Congress passed a bill that placed high tariffs on goods imported to the United States. The South believed the bill favored Northern manufacturing interests and denounced it as a “tariff of abominations.” Speaking for South Carolina, John C. Calhoun (then the vice president) claimed that any state could nullify (declare invalid) a federal law it deemed unconstitutional. In 1832, Congress lowered tariffs somewhat, but not enough to please South Carolina. South Carolina declared the tariff act “null and void” and threatened to secede from the Union if federal officials tried to collect tariffs in the state. This action created a constitutional crisis. Jackson believed in states’ rights, but he also thought the Union must be preserved. In 1833, he persuaded Congress to pass a force bill, a law that allowed him to use the armed forces to collect tariffs. But Congress lowered tariffs to a point acceptable to South Carolina, and the nullification crisis faded away.

Politics after Jackson.

Jackson’s influence on politics continued after he left office. As undisputed leader of the Democrats, Jackson chose Martin Van Buren to be the party’s candidate in the 1836 presidential election. Jackson’s opponents had formed the Whig Party four years earlier. In an effort to attract Jackson followers, most Whigs supported William Henry Harrison against Van Buren. Harrison, like Jackson, had won fame as an Indian fighter. But American voters, loyal to Jackson, elected Van Buren.

A depression called the Panic of 1837 crippled the U.S. economy shortly after Van Buren took office. The presidential election of 1840 again matched Van Buren and Harrison. In their campaign, the Whigs blamed Van Buren’s economic policies for the depression. They also promoted Harrison as a war hero and associated him with hard cider, the log cabin, and other symbols of the frontier. This time, Harrison won the election.

Immigration.

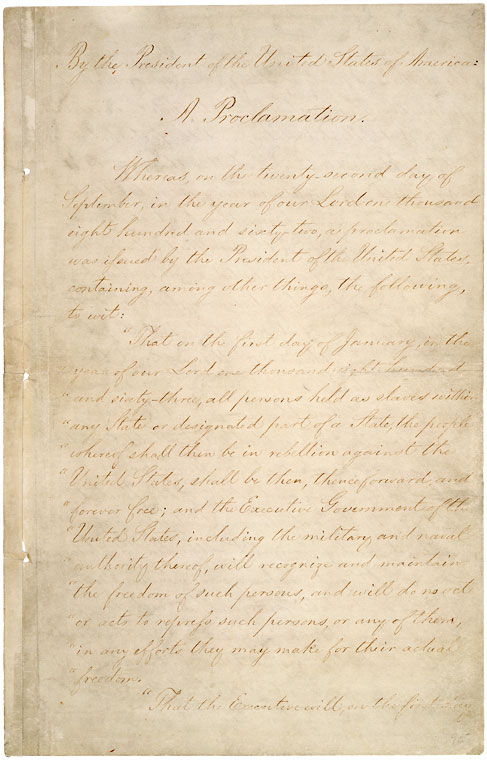

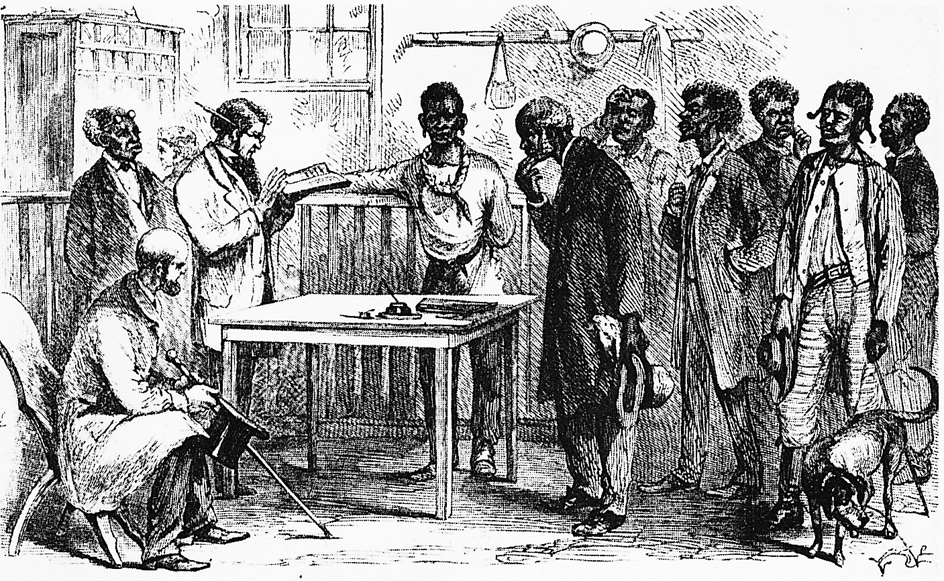

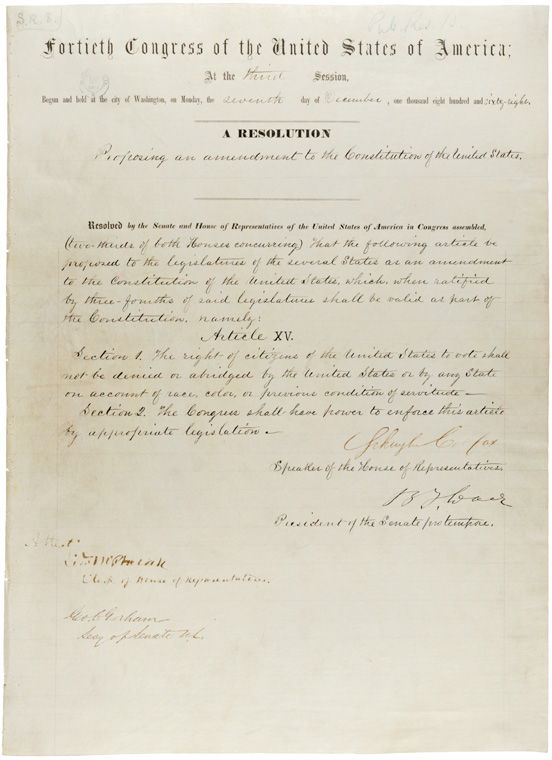

The United States had always been made up mainly of immigrants. But from 1845 through 1860, more than 100,000 immigrants arrived in the country every year. Most came to find opportunities in the growing U.S. economy. A majority settled in the North because slavery reduced the opportunities available to free workers in the South. The immigrants made major contributions to the economic growth of the United States. They came from many countries, but the largest numbers were from Ireland and Germany.