War of 1812 (1812-1815) was a conflict between the United States and the United Kingdom. The war stemmed largely from complaints that the British had been interfering with American shipping. The fighting began with an American invasion of British colonies in what is now Canada. During the course of the war, the British invaded Washington, D.C., and burned the U.S. Capitol and the White House.

The War of 1812 was in many ways the strangest war in the history of the two countries. It could well be named the “War of Faulty Communication.” Two days before war was declared, the British government stated that it would repeal the laws that were the chief reason for fighting. If there had been high-speed communication with Europe, the war might well have been avoided. Speedy communication could also have prevented the greatest battle of the war, which was fought at New Orleans 15 days after a treaty of peace had been signed.

The war was peculiar in other ways as well. Even though the dispute centered on the maritime trade, the great shipping section of the United States, New England, strongly opposed going to war. The American demand for war came chiefly from the Western and Southern states. In addition, the treaty of peace that ended the war settled none of the issues over which the war had supposedly been fought.

The War of 1812 was not an all-out struggle on either side. The United States, a young nation at that point, was ill-prepared for war. The United Kingdom, meanwhile, was engaged in a larger struggle with France and could devote only some of its resources to fighting in North America. When the War of 1812 ended, both the United States and the United Kingdom claimed victory. However, neither side had won decisively.

Causes of the war

The causes of the War of 1812 emerged during a long-running period of conflict between the British and French. Napoleon I (also known as Napoleon Bonaparte) had been head of the French government since 1799 and emperor since 1804. Through an aggressive campaign, he had made himself the master of continental Europe. Except for a short break from 1801 to 1803, the French and British had been fighting since 1793.

British and French blockades.

Napoleon had long hoped to invade and conquer the United Kingdom. However, in 1805, his navy was destroyed by the British at the Battle of Trafalgar. The defeat forced Napoleon to give up the idea of taking an army across the English Channel. Shifting strategy, Napoleon set out instead to ruin the United Kingdom by destroying British trade. Napoleon’s Berlin and Milan decrees, in 1806 and 1807, aimed to shut off British export markets in Europe. The United Kingdom, in turn, issued a series of Orders in Council (decrees) that declared a blockade of French ports and of ports that were under French control. See Continental System; Milan Decree.

The British and French blockades had disastrous effects on U.S. shipping. Before 1806, the United States had grown wealthy from the European war. American ships took goods to both the United Kingdom and France, and the value of this trade increased dramatically from 1791 to 1805. But now the picture suddenly changed. An American ship bound for a French port had to stop first at a British port for inspection and payment of fees. Otherwise, the British were likely to seize the ship. At the same time, Napoleon ordered neutral ships not to stop at British ports for inspection. He announced that the French would seize any American ships that they found had obeyed the British Orders in Council.

The British Royal Navy, the most powerful fleet in the world, controlled the seas. Therefore, American vessels generally chose to trade only with other neutral nations, with the United Kingdom, or under British license. A few adventurous merchants, in search of huge profits, continued the risky trade with continental Europe. The United States complained that both the French and British policies were illegal “paper blockades” that neither side could fully enforce. See Blockade (Paper blockade).

Impressment of seamen.

The British Royal Navy was in need of manpower, in part because hundreds of deserters from the navy had found work on American ships. The British government claimed the right to stop neutral ships at sea, remove sailors of British birth, and impress (conscript, or force) them into British naval service. The United States objected strongly to this practice, partly because many native-born Americans were impressed “by mistake.”

In June 1807, the American Captain James Barron of the Chesapeake refused to let members of a British warship, the Leopard, search his ship for deserters. The Leopard then fired on the Chesapeake. The British removed four men they claimed were deserters and hanged one of them. Anti-British feeling in the United States rose sharply as a result of the incident. President Thomas Jefferson ordered all British naval vessels out of American harbors. The British later apologized for the incident and paid for the damage done. Still, bitterness remained.

American reaction.

The United States tried several times to convince the British to change their policies on neutral shipping and impressment. In April 1806, the U.S. Congress passed a Non-Importation Act, which barred British goods from American markets. The act was not put into continuous operation until December 1807. By that time, the Chesapeake incident had taken place, and sterner measures were deemed necessary. That month, Congress passed the Embargo Act. This act prohibited exports from the United States and forbade American ships from sailing into foreign ports. The act was intended to exert pressure on the British and French.

The Embargo Act did not produce the results Congress desired. Overseas trade nearly stopped, almost ruining New England shipowners and putting many sailors out of work. Shipyards closed, and goods piled up in warehouses. The embargo also hurt Southern planters, who normally sold tobacco, rice, and cotton to the United Kingdom. Opponents of the Embargo Act described its effects on the United States by spelling the word backward. They called it the “O-Grab-Me” act. And because the British and French were so intent on winning the war in Europe, both sides refused to yield to American pressure. After 14 months, Congress gave up the embargo.

Seeking a new way to put pressure on British and French commerce, Congress passed the Non-Intercourse Act in March 1809. This act permitted American ships to trade with any countries but the United Kingdom and France. The act also opened American ports to all but British and French ships. This plan, however, also failed.

In 1810, Congress passed Macon’s Bill No. 2, which removed all restrictions on trade. The law included a provision that if either the United Kingdom or France would give up its orders or decrees, the United States would restore nonintercourse rules against the other nation, unless that nation also agreed to change its policy.

Napoleon, eager to get the United States into a war against the United Kingdom, pretended to repeal his Berlin and Milan decrees as they applied to U.S. ships. President James Madison then shut off all trade with the United Kingdom. In the summer of 1811, further attempts were made to reach an agreement with the British. These attempts failed, and in November, Madison advised Congress to prepare for war.

The War Hawks.

A group of young politicians known as “War Hawks” dominated the U.S. Congress during this period. The War Hawks came mostly from Western and Southern states and favored going to war with the United Kingdom. Henry Clay of Kentucky and John C. Calhoun of South Carolina were the leaders of the group. Clay was speaker of the House of Representatives.

The people of New England generally opposed going to war. They feared that a war with the United Kingdom would wipe out the New England shipping trade, which had already been heavily damaged. Also, many New Englanders sympathized with the British in their struggle against Napoleon.

Some historians have argued that territorial expansion and tensions with Indigenous (native) peoples were motivating factors for the War Hawks. Many American settlers in the West had encountered armed resistance from Indigenous groups (then called Indians), and the settlers believed the Indigenous groups had considerable British support. Friction between Westerners and Indigenous warriors climaxed in November 1811 at the Battle of Tippecanoe, near what is now Lafayette, Indiana. Warriors there attacked an American army, and British weapons were found on the battlefield. Still, the drive toward war was primarily rooted in deep resentment over the British actions at sea.

In 1812, the main concerns of Congress were maritime rights, national honor, and the country’s obligation to respond to foreign threats. The Federalists in Congress strongly opposed going to war. But the Democratic-Republicans believed that war was the only solution to America’s international problems. Prominent Democratic-Republicans at the time included Henry Clay, John C. Calhoun, and President James Madison.

Progress of the war

On June 1, 1812, President Madison asked Congress to declare war against the United Kingdom. He cited British impressments of American seamen and interference with American trade as reasons for going to war. He also charged that the British had stirred up resistance among Indigenous peoples.

On June 18, Congress voted by a narrow margin to declare war. Two days earlier, the British foreign minister had announced that the Orders in Council would be repealed. However, word of this announcement did not reach America until after the war had begun. Because President Madison had asked for the declaration of war, many Federalists blamed him for the conflict, calling it “Mr. Madison’s war.”

Congress had known for seven months that war was likely to come, but no real preparations had been made. There was little money in the U.S. treasury. The Regular Army had less than 10,000 troops, and very few trained officers. The Navy had fewer than 20 seagoing ships.

Adding to the nation’s difficulties, a large minority, both in Congress and in the country, was opposed to war. The declaration of war had passed by a vote of only 79 to 49 in the House and 19 to 13 in the Senate. New England, the richest area of the country, bitterly opposed the war, and it withheld both money and troops.

The war at sea.

At sea, the massive British fleet dwarfed the regular American navy. As a result, the United States depended largely on privateers. Privateers were armed ships owned by private individuals and given legal permission to attack British merchant vessels.

American naval vessels and privateers would do considerable damage to British commerce, taking about 1,500 prize ships in all. British warships and Canadian privateers would take almost the same number of American merchant ships. The United States, which had fewer ships than its enemy, suffered proportionally higher losses as a result. A British blockade was gradually clamped on the coast of the United States, and American trade almost disappeared. The loss of duties on imports pushed the U.S. treasury deeper into debt.

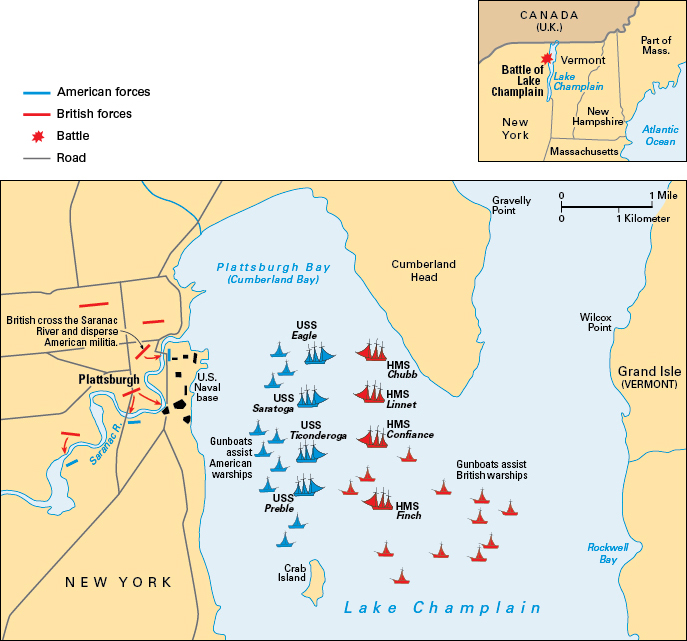

A few minor U.S. victories against British ships improved American morale, but they had little effect on the overall struggle. There would be two American naval victories of great consequence. They were the battles won by Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry on Lake Erie in 1813 and by Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough on Lake Champlain in 1814.

Campaigns of 1812.

The American plan of attack called for a three-way invasion of Canada. Invasion forces were to start from three points: the city of Detroit; the Niagara River, between New York and Canada; and the foot of Lake Champlain, between New York and Vermont.

At Detroit, General William Hull led about 2,000 U.S. troops across the Detroit River into Canada. However, the British commander, General Sir Isaac Brock, led a small force against Hull’s troops, and Hull retreated to Detroit. In August, Brock attacked Hull’s forces and captured both the city of Detroit and Hull’s entire army. The British and Indigenous warriors also captured Michilimackinac and Fort Dearborn (Chicago).

During the fall of 1812, the scene shifted to the Niagara area. General Brock, the British commander, had about 2,000 men scattered along the 35 miles (56 kilometers) of the Niagara River. American troops in the area, under Generals Stephen Van Rensselaer and Alexander Smyth, numbered more than 6,000. On October 13, a large American force tried to cross the Niagara River at the Canadian village of Queenston, about 5 miles (8 kilometers) below Niagara Falls. Several hundred Americans made it to the other side of the river, where they were attacked by Brock’s men. Brock was fatally wounded in the fighting, which came to be known as the Battle of Queenston Heights. Later in the day, after both sides received reinforcements, the British drove the invaders to the riverbank. Unable to get back across the Niagara, more than 900 Americans surrendered.

At Lake Champlain, a third American army advanced from Plattsburgh, New York, to the Canadian frontier. However, the militia (citizen army) soldiers refused to leave American territory, and the army marched back to Plattsburgh. Thus the first American attempts to invade Canada had failed completely.

Campaigns of 1813.

In January 1813, U.S. Brigadier General James Winchester led a detachment of Kentucky troops toward Detroit. On January 18, his men defeated Canadian militia and Indigenous warriors at Frenchtown (now Monroe, Michigan) on the Raisin River (also known as the River Raisin). But on January 22, British Colonel Henry Procter (also spelled Proctor) led a force of about 1,100 British and Indigenous troops to victory over Winchester’s force. After the battle, the British departed with the able-bodied American prisoners, leaving the wounded Americans behind with Indigenous warriors. The warriors killed some of the wounded prisoners.

In April, American troops captured York (now Toronto), the capital of the British colony of Upper Canada, and burned some of the city’s public buildings. The Americans then invaded the Canadian side of the Niagara and captured Fort George. Attempts to advance farther were stopped by British victories at Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams in June. The Niagara campaign of 1813, which had been successful at first, bogged down.

In September and early October, many of the American troops in the Lake Ontario region moved to Sackets Harbor, at the eastern end of the lake, to take part in a two-pronged attack on the city of Montreal, in Canada. Led by Major General James Wilkinson, the force at Sackets Harbor was to continue east along the Saint Lawrence River. Another force, under Major General Wade Hampton, was to move north from Lake Champlain toward Montreal. The plan failed, however. Hampton was defeated at the Battle of Châteauguay in October. Wilkinson lost the Battle of Crysler’s Farm in November.

On September 10, an American naval squadron under Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry defeated a British squadron at the western end of Lake Erie. The battle forced the British to pull out of Detroit and retreat into Canada. The retreating group included about 800 British troops and 500 warriors under their chief, Tecumseh. Major General William Henry Harrison led about 3,000 U.S. troops across the Detroit River in pursuit.

On October 5, the British halted near Moraviantown, on the Thames River in what is now Kent County, Ontario. The Americans advanced, and the British—led by Henry Procter, now a brigadier general—fled soon after the battle began. The Indigenous forces, however, held their ground and suffered heavy losses. The famed Shawnee leader Tecumseh died on the battlefield. His death broke the league of Indigenous tribes that had been allied to the British.

In December, the British crossed the Niagara River and captured Fort Niagara. They burned Buffalo and neighboring villages. The actions were retaliation for the American burning of the Canadian town of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake).

Campaigns of 1814.

In the spring of 1814, Napoleon was defeated in Europe. The end of fighting there enabled the United Kingdom to send reinforcements to North America, thus ending American hopes of conquest. However, the United States had at last created a well-trained and disciplined army on the Niagara frontier. Under the able leadership of Major General Jacob Brown, this army invaded Canada in early July and defeated the British at the Battle of Chippewa (also spelled Chippawa).

Later in July, the Americans engaged the British at Lundy’s Lane, about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) from Niagara Falls. On July 25, U.S. General Winfield Scott was moving toward Queenston with about 1,100 soldiers, and he came upon about 1,900 British troops. The two sides began fighting around 7 p.m. Within a few hours, General Brown had arrived on the field with about 1,600 reinforcements from Chippewa. About 1,700 British reinforcements also appeared. The battle raged until midnight, and the losses were heavy. Both sides claimed victory at Lundy’s Lane. The Americans drove the British from their position and captured the British artillery. However, the Americans neglected to remove the guns from the field when they withdrew to Chippewa, and the British repossessed their artillery.

Following Lundy’s Lane, American forces fell back to Fort Erie, in Canada. The fort stood where Lake Erie drains into the Niagara River. The Americans strengthened the defenses of the fort. They withstood a British assault in August and forced the British to end a siege in September. In November, the Americans withdrew to the United States.

Around the same time, about 10,000 British troops under General Sir George Prevost moved into New York by way of Lake Champlain. Prevost wanted to capture the American naval base at Plattsburgh, and he had the support of a small British naval squadron on the lake. On September 11, however, this squadron was defeated and captured in a clash with an American squadron under Master Commandant Thomas Macdonough. Prevost chose to retreat to Canada.

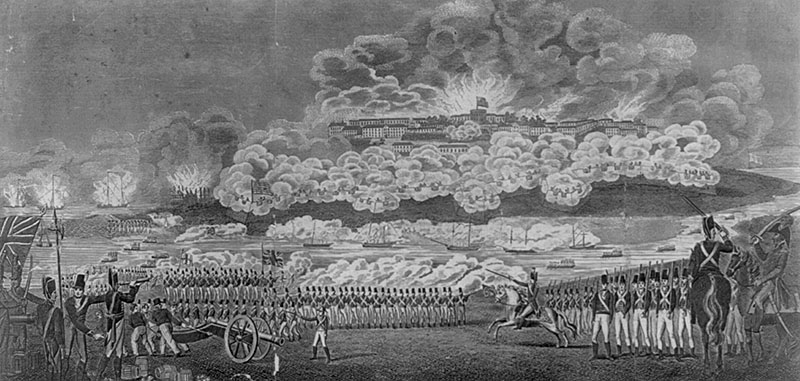

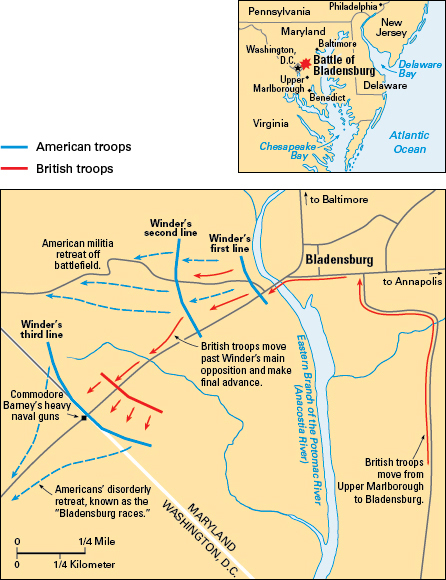

In an attempt to draw American troops away from the northern theater, another British army, under General Robert Ross, landed in Chesapeake Bay. In late August, Ross’s troops scattered the American troops at the Battle of Bladensburg and occupied Washington, D.C. The British then set fire to the Capitol, the White House, and other public buildings.

A British attempt to capture Baltimore was stopped in September. British warships bombarded Fort McHenry, which protected the city, but they could not break its defenses. The battle inspired Francis Scott Key to write “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

“The needless battle.”

The Battle of New Orleans, the last major engagement of the war, was fought on Jan. 8, 1815. It is considered “the needless battle” because a treaty of peace had been signed 15 days earlier. The treaty had not yet been ratified.

At the Battle of New Orleans, a British force of more than 8,000 attacked entrenchments that had been built under the direction of U.S. General Andrew Jackson. American artillery and riflemen killed or wounded about 1,500 British soldiers, including the commanding officer, General Sir Edward Pakenham. There were few American casualties (people killed, wounded, or captured). Although the battle had no effect on the outcome of the war, the victory helped to bring about a surge of American nationalism. It also brought fame to Jackson, who later became president.

Treaty of Ghent.

After more than two decades of conflict with France, the British public had grown tired of war and especially of war taxes. At the same time, an increasing number of Americans feared disaster if the war continued. Commissioners from the two countries met at Ghent, Belgium (then part of the Netherlands), in August 1814.

The British at first insisted that the United States give up territory on its northern border and set up a large permanent “boundary state” for Indigenous peoples in the Northwest. However, American victories in the summer and fall of 1814 led the British to drop these demands. A treaty was finally signed in Ghent on Dec. 24, 1814. It was ratified in Washington, D.C., on Feb. 17, 1815.

By the terms of this treaty, all land that had been captured by either nation was to be given up. Conditions were to be exactly as they were before the war, and commissions from both of the countries were to settle any disputed points about boundaries. Nothing was said in the treaty about impressments of American seamen, blockades, or the British Orders in Council—the chief issues that had driven the countries to war.

Results of the war

Thousands of people were killed in the War of 1812, though exact casualty numbers are difficult to verify. The total number of American battle deaths has been estimated at 2,260, with about 4,500 wounded. Estimates of British and Indigenous casualties vary. Some historians have estimated the number of British battle deaths at around 2,000, with thousands more wounded. In addition, disease and hardship caused by the war led to many deaths among the soldiers and civilians on all sides.

The United States faced near disaster in 1814, but it emerged from the war a stronger, more unified nation. The seemingly successful struggle against the British led to a surge in American patriotism and a heightened sense of unity. A period of general harmony that followed the war became known as the Era of Good Feeling.

The War of 1812 settled none of the issues over which it was fought, but most of these issues faded away over time. In the long period of peace after 1815, the British had no occasion to make use of impressments or blockades. Conflicts with Indigenous groups in the American Northwest were reduced by the death of Tecumseh and by the rapid settlement of the region. The United States occupied part of Florida during the war, and it was soon able to purchase the rest from Spain.

Both Andrew Jackson and William Henry Harrison won military fame during the war, and both would go on to serve as president of the United States. Another political effect of the war was the decline of the Federalist Party. New England leaders, most of them Federalists, had met secretly in Hartford, Connecticut, to study ways to protest the conduct of the war. Their opponents accused them of plotting treason, and the Federalists never recovered (see Hartford Convention).

Some historians believe the War of 1812 promoted unity and patriotism in the British colonies of North America, setting the stage for Canada’s emergence as a nation. Several of the colonies confederated in 1867 to form the Dominion of Canada, which eventually expanded and developed into present-day Canada. In the United Kingdom, the War of 1812 was in many ways forgotten. British people had largely viewed the conflict as a sideshow to the far greater struggle against France.