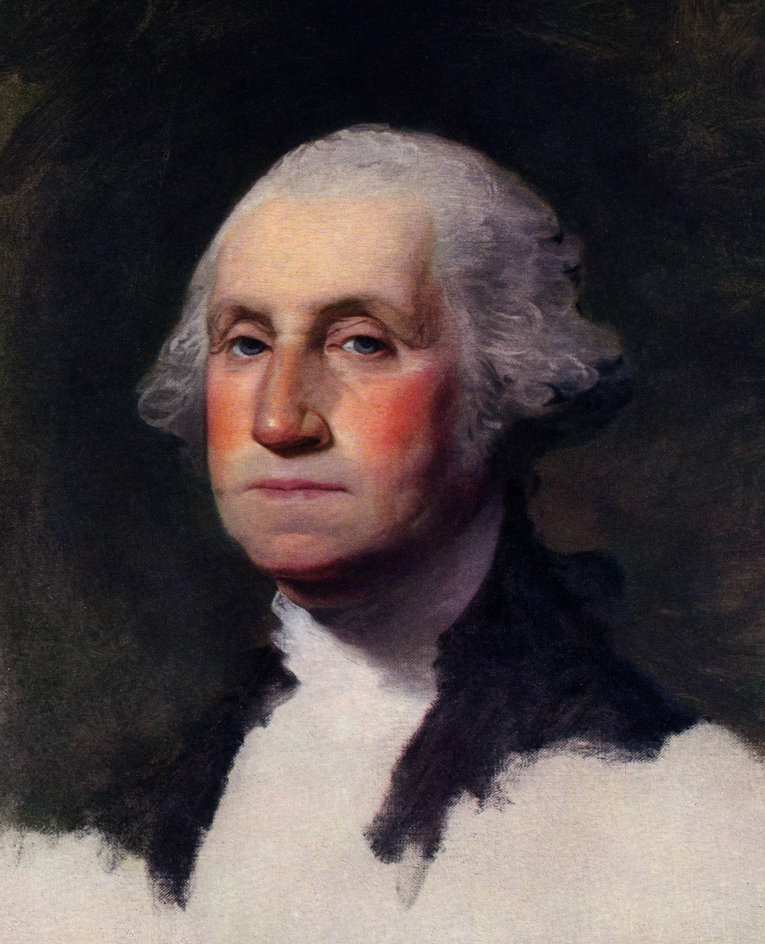

Washington, George (1732-1799), won a lasting place in American history as the “Father of the Country.” For nearly 20 years, he guided his country much as a father guides a growing child.

In three important ways, Washington helped shape the beginning of the United States. First, he commanded the Continental Army that won American independence from Britain in the American Revolution (1775-1783). Second, Washington served as president of the convention that wrote the Constitution of the United States. Third, he was elected the first president of the United States.

Loading the player...Washington, the first President of the United States of America

Most Americans of his day loved Washington. His army officers would have tried to make him king if he had let them. From the American Revolution on, his birthday was celebrated each year throughout the country.

Washington lived an exciting life. As a boy, he explored the wilderness. When he grew older, he helped the British fight the French and Indians. Several times, he was nearly killed. As a general, he suffered hardships with his troops. Perhaps the worst were the cold winters at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, and Morristown, New Jersey. He lost many battles. But he led the American army to final victory at Yorktown, Virginia. After he became president, he solved many problems in turning the plans of the Constitution into a working government.

Washington went to school only until he was about 14 or 15. But he learned to make the most of all his abilities and opportunities. Washington’s patience and understanding of others helped him win people to his side.

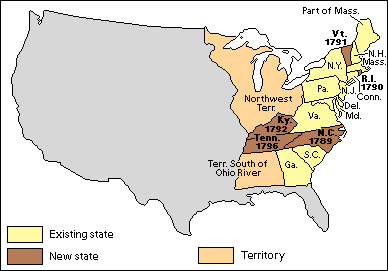

There are great differences between the United States of Washington’s day and that of today. The new nation was small and weak. It stretched west only to the Mississippi River. It had fewer than 4,000,000 people. Most people made their living by farming. Few children went to school. Many men and women could not read or write. Transportation and communication were slow. It took Washington three days to travel about 90 miles (140 kilometers) from New York City to Philadelphia. That was longer than it now takes to fly around the world. There were only 11 states in the Union when Washington became president. There were 16 when he left office.

Many stories have been told about Washington. Most are probably not true. So far as we know, he did not chop down his father’s cherry tree, then confess by saying: “I cannot tell a lie, Pa.” He probably never threw a stone across the Rappahannock River. But such stories show that people were willing to believe almost anything about his honesty and his strength. One of Washington’s officers, Henry “Light Horse” Lee, summed up the way Americans felt and still feel about Washington: “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Washington the man

Washington’s appearance caused admiration and respect. He was tall, strong, and broad-shouldered. As he grew older, cares lined his face and made him look stern. Perhaps the best description of Washington was written by a friend, George Mercer, in 1760:

“He may be described as being straight as an Indian, measuring 6 feet 2 inches in his stockings, and weighing 175 pounds … A large and straight rather than a prominent nose; blue-gray penetrating eyes … He has a clear though rather colorless pale skin which burns with the sun … dark brown hair which he wears in a queue …

His mouth is large and generally firmly closed, but which from time to time discloses some defective teeth … His movements and gestures are graceful, his walk majestic, and he is a splendid horseman.”

Washington set his own strict rules of conduct. But he also enjoyed having a good time. He laughed at jokes, though he seldom told any.

One of the best descriptions of Washington’s character was written after his death by Washington’s fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson:

“His mind was great and powerful … as far as he saw, no judgment was ever sounder. It was slow in operation, being little aided by invention or imagination, but sure in conclusion. …

“Perhaps the strongest feature in his character was prudence, never acting until every circumstance, every consideration, was maturely weighed; refraining if he saw a doubt, but, when once decided, going through with his purpose, whatever obstacles opposed.

“His integrity was most pure, his justice the most inflexible I have ever known …

“He was, indeed, in every sense of the words, a wise, a good and a great man. … On the whole, his character was, in its mass, perfect … it may truly be said, that never did nature and fortune combine more perfectly to make a man great …”

Early life (1732-1746)

Family background.

Washington inherited more than a good mind and a strong body. He belonged to an old colonial family that believed in hard work, in public service, and in worshiping God. The Washington family has been traced back to 1260 in England. The name at that time was de Wessington. It was later spelled Washington. Sulgrave Manor in England is the home of George Washington’s ancestors.

George’s great-grandfather, John Washington (1632-1677), came to America by accident. He was mate on a small English ship that went aground in the Potomac River in 1656 or 1657. By the time the ship was repaired, he had decided to marry and settle in Virginia. He started with little money. Within 20 years, he owned more than 5,000 acres (2,000 hectares). His property included the land that later became Mount Vernon. Lawrence Washington (1659-1698), the oldest son of John, was the grandfather of George.

Washington’s parents.

George’s father, Augustine Washington (1694-1743), was Lawrence’s youngest son. After iron ore was discovered on some of his land, he spent most of his time developing an ironworks. He had four children by his first wife, Jane Butler. She died in 1729. In March 1731, he married Mary Ball (1709?-1789), who became George’s mother.

Mary Ball did not have a very happy childhood. Her father and mother both died before she was 13. Although she had inherited property from her mother, she spent all her life worrying about money. After her son George became a man, she wrote him many letters asking for money even though she did not always need it.

Augustine and Mary Ball Washington had six children. Besides George, there were Betty (1733-1797), Samuel (1734-1781), John Augustine (1736-1787), Charles (1738-1799), and Mildred (1739-1740).

Boyhood.

George Washington was born on Pope’s Creek Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, on Feb. 22, 1732 (February 11, on the Old Style Calendar then in use). When George was about 3 years old, his family moved to the large, undeveloped plantation that was later called Mount Vernon. It lay about 50 miles (80 kilometers) up the Potomac River in Virginia. The plantation was then called Little Hunting Creek Farm. George’s only playmates were his younger sister and brothers. No neighbors lived close by. George probably enjoyed exploring the nearby woods and helping out in farm work. He saw little of his father. The older man made many trips to his ironworks, about 30 miles (48 kilometers) away.

In 1738, when George was nearly 7, his father decided to move closer to the ironworks. He bought the 260-acre (105-hectare) Ferry Farm. It lay on the Rappahannock River across from Fredericksburg, Virginia.

Education.

George probably began going to school in Fredericksburg soon after the family moved to Ferry Farm. No accurate records have been found that tell who his teachers were. Altogether, he had no more than seven or eight years of school. His best subject was arithmetic. He wrote his lessons in ink on heavy paper. His mother or a teacher then sewed the paper into notebooks.

George studied history and geography. But he never learned as much about literature, languages, and history as did Thomas Jefferson or James Madison. They had the advantage of much more education.

By the time he ended his schoolwork at the age of 14 or 15, George could keep business accounts and do simple figuring. He could also write clear letters. During the rest of his life, he kept diaries and careful accounts of his expenses.

George’s father had probably planned to send him to school in England because there were few schools in Virginia. But Augustine Washington died when George was only 11. The plans came to nothing. After his father’s death, George’s mother did not want him away from home. George was to inherit Ferry Farm when he reached 21. Meanwhile, he, his younger sister and brothers, and the farm were in the care of his mother.

Plantation life.

Growing up at Ferry Farm, young George helped manage a plantation worked by 20 black slaves. He was observant and hard-working. He learned how to grow tobacco, fruit, grains, and vegetables. He saw how many things a plantation needed to keep operating, such as cloth and iron tools. He also developed his lifelong love for horses. At the same time, Washington enjoyed the life of a young Virginia country gentleman. He had boyhood romances and wrote love poems. He became a good dancer. He enjoyed hunting, fishing, and boating on the river.

Development of character.

As a youth, Washington was sober, quiet, attentive, and dignified. His respect for his elders and his dependability made him admired. He experienced the hardships of colonial life on the edge of the wilderness. He learned that life was difficult. This knowledge helped make him become strong and patient.

As a schoolboy, Washington copied rules of behavior in an exercise book. His mother or a teacher may have suggested he do so. Following are some of these rules in his own spelling, capitalization, and punctuation:

Turn not your Back to others especially in Speaking, Jog not the Table or Desk on which Another reads or writes, lean not upon any one. Use no Reproachfull Language against any one neither Curse nor Revile. Play not the Peacock, looking every where about you, to See if you be well Deck’t, if your Shoes fit well, if your Skokings Sit neatly, and Cloths handsomely. While you are talking, Point not with your Finger at him of Whom you Discourse nor Approach too near him to whom you talk especially to his face. Be not Curious to Know the Affairs of Others neither approach those that Speak in Private. It’s unbecoming to Stoop much to ones Meat Keep your Fingers clean & when foul wipe them on a Corner of your Table Napkin.

George Washington’s admiration for his half brother Lawrence (1718-1752) also influenced his development. Lawrence had been educated in England. He had the polish of a young English gentleman. From 1740 to 1742, Lawrence had gone to South America as a Virginia volunteer captain in a brief war between Britain and Spain. Lawrence took no part in the actual fighting. But he returned to Virginia with many war stories. These tales excited George’s imagination. George often visited the fashionable new house that Lawrence had built at Mount Vernon.

Lawrence decided that 14-year-old George should join the British Royal Navy. George wanted to go. But he needed his mother’s permission. No matter how much he argued, she would not let him go. She asked advice of her half brother, Joseph Ball. He suggested somewhat jokingly that rather than let George become a sailor, it would be better to apprentice him to a tinker, a mender of pots and pans.

Washington the surveyor (1747-1752)

After teenaged George Washington gave up hopes of becoming a sailor, he became interested in exploring the frontier. Becoming a surveyor and marking out new farms in the wilderness would give him a chance to seek adventure and earn money. He enjoyed mathematics. He easily picked up an understanding of fractions and geometry. Then he took his father’s old set of surveying instruments out of storage. At 15, he began studying to be a surveyor.

On one of his visits to Mount Vernon, George met Lord Fairfax, the largest property owner in Virginia. Fairfax was a cousin of Lawrence Washington’s wife. He owned more than 5 million acres (2 million hectares) of land in northern Virginia. These lands extended to the Allegheny Mountains and included much of the Shenandoah Valley.

First expedition.

Lord Fairfax began planning an expedition to survey his western lands. James Genn, an expert surveyor, was put in charge of the expedition. Sixteen-year-old George Washington was invited along. The boy persuaded his mother to let him make his first long trip away from home.

The monthlong expedition set out on horseback in March 1748. Washington learned to sleep in the open and hunt for food. By the time he returned to Mount Vernon, he felt he had grown into a man.

Professional surveyor.

In July 1749, Washington was appointed official surveyor for Culpeper County. In November, Lord Fairfax allowed him to make a short surveying trip on his own to the Allegheny Mountains.

Washington lived at Mount Vernon for part of that winter. His surveying work paid him well. It was one of the few occupations in which a person could expect to be paid in cash. Most other business in Virginia was carried on with payments in tobacco. Washington kept track in his account book of small loans he made to his relatives and friends. He also wrote down winnings and losses at cards and billiards.

During the next three years, Washington made more surveys as settlers moved into the Shenandoah Valley. He saved his money. When he saw a good piece of land, he bought it. By 1752, he owned about 2,300 acres (930 hectares).

Only foreign trip.

In 1751, George Washington made his only trip away from America. Lawrence Washington had become ill. He decided to sail to the warm climate of Barbados Island in the British West Indies, a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea, for his health. He asked George to go along.

The brothers arrived at the island in November. George’s diary shows he was interested in comparing farming methods on the island with those of Virginia. Two weeks after arriving, George became ill with smallpox. He carried a few pox scars on his face the rest of his life. A week after recovering, George decided to return to Virginia while Lawrence remained in the tropics.

George was now 20. He fell in love with 16-year-old Betsy Fauntleroy, the daughter of a Richmond County planter and shipowner. George proposed to her at least twice. Each time he was refused. He sadly wrote that she had given him a “cruel sentence.”

In early June 1752, Lawrence Washington suddenly returned home. He died of tuberculosis before the end of the month. Lawrence left Mount Vernon to his wife for as long as she lived, then to his daughter. He provided that the estate should go to George if his daughter died with no children of her own. He also left George an equal share of his land in the Shenandoah Valley with his other three brothers.

Early military career (1753-1758)

At the age of 20, George Washington had no experience or training as a soldier. But Lawrence’s war stories had interested him in military affairs. He applied to the governor for a commission in the militia. In December 1752, he was commissioned as a major. He was put in charge of training militia in southern Virginia. Washington probably prepared for his new duties by reading books on military drills and tactics.

Messenger to the French.

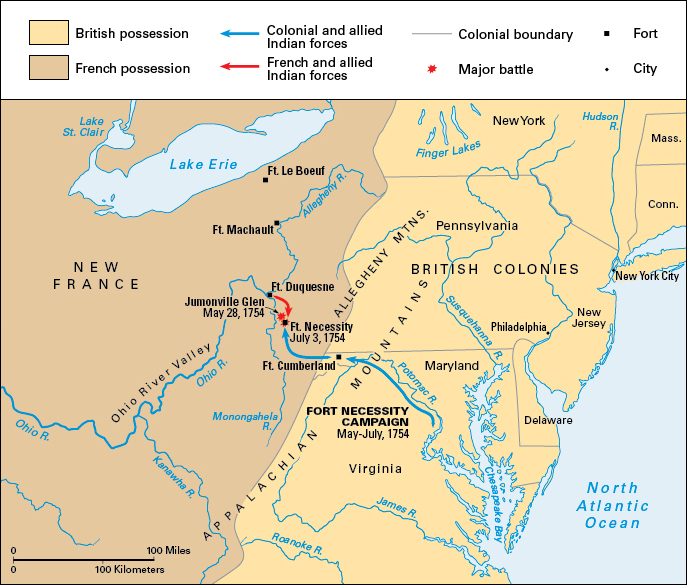

In October 1753, Washington learned that Robert Dinwiddie, the acting governor of Virginia, planned to send a message to the French military commander in the Ohio River Valley. Dinwiddie intended to warn the French that they must withdraw their troops from the region. Both the French and the British wanted the Ohio River Valley for fur trading. British speculators also wanted to invest in land there. Washington volunteered to carry the message. Dinwiddie gave him the task.

In mid-November, Washington set out on the dangerous trip. With him went Christopher Gist, a frontier guide. He also took an interpreter and four frontiersmen. Washington’s party traveled north into western Pennsylvania. Sometimes, the men covered as much as 20 miles (32 kilometers) in a day. They stopped at an Indian village near the site of present-day Pittsburgh. There, three Indian chiefs agreed to accompany the party to visit the French. The Indians gave George the name Conotocarious, which meant Towntaker.

Early in December, Washington reached French headquarters at Fort Le Boeuf. The fort stood just south of present-day Erie, Pennsylvania. The French commander rejected Dinwiddie’s warning. He said that his orders were to take and hold the Ohio River Valley. He gave Washington a letter to carry back to the British. Washington experienced many hardships and dangers on the return trip. It was late December and bitterly cold. Snow lay deep on the ground. Once Washington nearly drowned trying to cross the Allegheny River on a raft.

On Jan. 16, 1754, Washington reached Williamsburg, Virginia. He delivered the French reply to Dinwiddie. Washington urged Dinwiddie to build a fort where the Ohio and Allegheny rivers joined (the site of present-day Pittsburgh). He also drew a detailed map of the region. Before the end of the month, Dinwiddie ordered a force of frontiersmen to build the fort. The governor had unknowingly taken the first step toward the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The war spread to many other countries. It was known in Canada and Europe as the Seven Years’ War.

First military action.

The 22-year-old Washington was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He received orders to enlist troops to man the new fort. He found Americans resentful because the Virginia government refused to pay them as much as regular British soldiers. Washington himself threatened to resign because his pay was lower than that of a lieutenant colonel in the regular British Army. Perhaps for the first time, he realized that American colonists were treated unfairly. It also may have been the first time he thought of himself as an American rather than as an Englishman.

Washington set out with about 160 poorly trained soldiers in April 1754. He was still 100 miles (160 kilometers) from the fort when he learned the French had captured it. Washington decided to move on toward the fort. The French had named it Fort Duquesne.

On May 28, 1754, Washington’s men fired the first shots of the war. He surprised a group of French troops. His forces killed 10, wounded 1, and took 21 prisoners. Only one of Washington’s men was killed. Washington described the short fight: “I heard bullets whistle and believe me there is something charming in the sound.”

Surrender of Fort Necessity.

Washington’s men built a fort about 60 miles (97 kilometers) south of Fort Duquesne. They completed it in June and named it Fort Necessity. Meanwhile, Washington had been promoted to the rank of colonel.

Early in June, about 180 Virginia soldiers arrived to reinforce Fort Necessity. Some friendly Indians also joined Washington’s forces. But no food arrived. On June 14, just as the last food was eaten, a company of about 100 British Regular Army troops arrived. They brought with them some supplies.

On July 3, the French attacked Fort Necessity. Washington had fewer than 400 men. Many of the troops were sick. All of them were hungry. The French fired from behind trees and rocks. About 30 of Fort Necessity’s defenders were killed and 70 wounded. A rainstorm turned the battlefield into a sea of mud. As night fell, the young colonel had few men, little food, and no dry gunpowder. His position was hopeless. About midnight, Washington agreed to surrender Fort Necessity. The French let him march out of the fort and return to Virginia with his men and guns.

A discouraged Washington returned to Williamsburg two weeks later. The colonists did not blame the young colonel for losing the fort. They praised Washington and his men for their bravery.

In October, Washington again visited Williamsburg. He was shocked when Dinwiddie told him he had orders from London not to allow colonial officers to have ranks above captain. Washington wanted a military career. But he resigned, rather than be lowered from the rank of colonel to captain.

Washington had inherited Ferry Farm from his father. But he did not wish to go there to live with his mother. Instead, he rented Mount Vernon from the widow of his half brother Lawrence. He agreed to pay a rent of 15,000 pounds (6,800 kilograms) of tobacco a year.

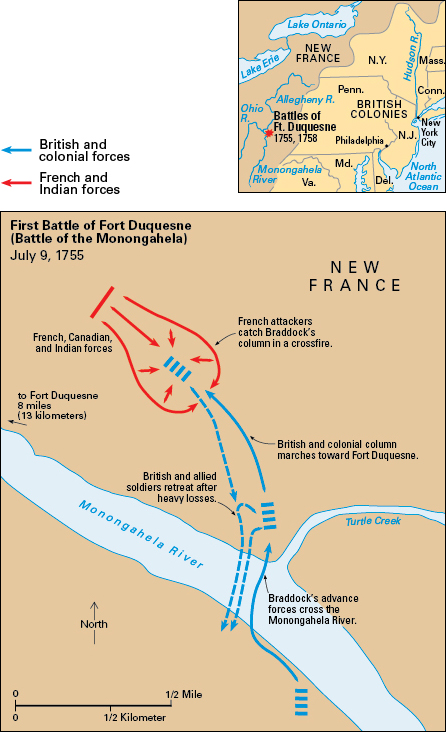

Braddock’s defeat.

In March 1755, Washington received a message from Major General Edward Braddock. The British general invited Washington to help him in a new campaign against the French at Fort Duquesne. Washington agreed to serve without pay as one of Braddock’s aides. He believed this was an opportunity to learn from an experienced general.

Braddock assembled his forces at Fort Cumberland, Maryland, about 90 miles (140 kilometers) southeast of Fort Duquesne. On June 7, the troops started across the rough country. Washington was upset by the slow march. He wrote in a letter: “They were halting to level every mole hill, and to erect bridges over every brook; by which means we were 4 days getting 12 miles.”

During the second week of the march, Washington became ill with a high fever. He was forced to remain behind in camp for two weeks. He warned Braddock to be careful of “the mode of attack which, more than probably, he would experience from the Canadian French, and their Indians.”

On July 9, the British had nearly reached Fort Duquesne. After making two dangerous crossings of the Monongahela River, Braddock ordered his long column to march forward. Wearing bright red uniforms, the British soldiers looked as though they were parading before the king. Washington was not yet well. But he had rejoined the army and rode his horse with pillows tied to the saddle. Braddock was confident that the French now would wait at their fort for his attack. What happened next was later described by Washington:

“We were attacked (very unexpectedly I must own) by about 300 French and Indians; our numbers consisted of about 1300 well armed men, chiefly regulars, who were immediately struck with such a deadly panic, that nothing but confusion and disobedience of orders prevailed amongst them.

“… the English soldiers … broke and ran as sheep before the hounds … The general (Braddock) was wounded behind the shoulder, and into the breast; of which he died three days after …

“I luckily escaped without a wound, though I had four bullets through my coat and two horses shot under me …”

With Braddock’s defeat and death, Washington was released from service. He rode home to Mount Vernon. Shortly after, in a letter to one of his brothers, he summed up his military career thus far:

“I was employed to go a journey in the winter (when I believe few or none would have undertaken it) and what did I get by it? My expenses borne! I then was appointed with trifling pay to conduct a handful of men to the Ohio. What did I get by this? Why, after putting myself to a considerable expense in equipping and providing necessaries for the campaign—I went out, was soundly beaten, lost them all—came in, and had my commission taken from me, or in other words, my command reduced, under pretense of an order from home … I have been on the losing order ever since I entered the service …”

Frontier commander.

The French encouraged the Indians to attack English settlers. In August 1755, Dinwiddie persuaded Washington to accept a new commission as colonel. Washington would take command of Virginia’s colonial troops to defend the colony’s 350-mile (563-kilometer) western frontier.

Many of the Virginians recruited by Washington and his officers were homeless men. Sometimes Washington had less than 400 of the 1,500 troops that he was supposed to have. Often he had to call the militia to help him. But the militia would not stay with him long. Many of the militia did not even have weapons.

Washington constantly urged that a new attack be made on Fort Duquesne. The British finally decided in 1758 to attack Fort Duquesne again. An advance British force of 800 men again was ambushed by the French and Indians. More than 300 British soldiers were killed. When the main army, including Washington, finally reached the fort in late November, the French had burned it and retreated toward Canada.

Washington returned to Virginia to hang up his sword. He was now the most famous American-born soldier. He knew how to train other soldiers and how to run an army. More important, he had shown courage and patience in leading his men.

The peaceful years (1759-1773)

At the age of 26, Washington turned to seeking happiness as a country gentleman and to building a fortune. During the next 16 years, he became known as a skilled farmer and an intelligent businessman. He was also a popular legislator, a conscientious warden of the Church of England, and a wise county court judge.

Marriage.

On Jan. 6, 1759, Washington married Martha Dandrige Custis. She was a widow, eight months older than George. The marriage probably took place in New Kent County, Virginia, at the bride’s plantation home. Her home was called the White House. Her first husband had left a fortune of about 18,000 acres (7,300 hectares) of land and 30,000 pounds. This was divided equally among the widow and her two children, John “Jackie” Parke Custis (1754-1781) and Martha “Patsy” Parke Custis (1756-1773). Washington became a loving stepfather to the children. He and Martha had no children of their own.

Legislator.

After a six-week honeymoon at the White House, Washington took his new family to Williamsburg. There he served for the first time in the colonial legislature. He had been elected to the House of Burgesses in 1758, while still on the frontier. Although he had not personally campaigned, he had paid bills for his friends to entertain voters during the campaign.

During the next 15 years, Washington was reelected time after time to the legislature. He seldom made speeches. He did not put any important bills before the legislature. But he learned the process of representative government. He saw the difficulties in getting a law passed. The experience gave him patience in later years when he had to deal with Congress during the revolution and as president. He also became acquainted with Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, and other Virginia leaders.

Farmer and landowner.

Washington brought his wife and children to Mount Vernon in April 1759. He found it run down by the neglect of his overseers.

In 1761, Washington inherited Mount Vernon because his half brother Lawrence’s widow and daughter had both died. He began to buy farms that lay around the estate. He also bought western lands for future development. In 1770, Washington made a trip west as far as the present town of Gallipolis, Ohio, searching for good land to buy. By 1773, he owned about 40,000 acres (16,000 hectares). Washington also controlled the large Custis estate of his wife and her children. He rented much of his land to tenant farmers.

Washington was a careful businessman. He did his own bookkeeping. He recorded every penny of expense or profit. His ledgers tell us when he bought gifts for his family, and what prices he received for his crops.

As a large landowner, Washington had to supervise many different activities. He wanted to learn more about farming, so he bought the latest books on the subject. When he discovered he could not grow the best grade of tobacco at Mount Vernon, he switched to raising wheat. He saw the profit in making flour, so he built his own flour mill. Large schools of fish swam in the Potomac River. Mount Vernon became known for the barrels of salted fish it produced. Washington experimented with tree grafting to improve his fruit orchards.

Social life

at Mount Vernon revolved around visitors. Many people came there for pleasure as well as for business. The men often joined Washington in his favorite sport, fox hunting. Both men and women enjoyed dining and playing cards in the mansion. Washington often visited other plantations. Several times a year, he went to such towns as Williamsburg and Alexandria, Virginia, and Annapolis, Maryland. There he would attend plays and dances, watch horse races, and shop.

The coming revolution (1774-1775)

The American colonists in the late 1760’s and early 1770’s grew angrier and angrier at the taxes placed on them by Britain. As a legislator and as a leading landowner, Washington was concerned as relations with Britain worsened. During this time, his knowledge of colonial affairs increased. He read many newspapers and political pamphlets. He often discussed the growing crisis with his neighbor, George Mason, a leading statesman of the time.

Lord Botetourt, the British governor, dismissed the Virginia legislature in 1769 because the representatives had protested the taxation imposed by the British Townshend Acts. Washington met with other legislators in a Williamsburg tavern. He presented a plan that he and Mason had discussed for forming an association to boycott imports of British goods. The plan was adopted.

Washington became one of the first American leaders to consider using force to “maintain the liberty of the colonies.” He wrote Mason in April 1769: “… That no man should scruple, or hesitate a moment to use arms in defense of so valuable a blessing, on which all the good and evil of life depends, is clearly my opinion; yet Arms I would beg leave to add, should be the last … resort.”

In 1774, the British closed the port of Boston as punishment for the Boston Tea Party. Virginia legislators who protested were dismissed by Governor Lord Dunmore. Again the representatives met as private citizens. They elected seven delegates, including Washington, to attend the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia. Washington wrote: “… shall we supinely sit and see one province after another fall a prey to despotism?”

First Continental Congress.

The Continental Congress met in September 1774. There, Washington had his first chance to meet and talk with leaders of other colonies. The members were impressed with his judgment and military knowledge. Washington made no speeches. He was not appointed to any committees. But he worked to have trade with Britain stopped by all the colonies. The trade boycott was approved by the Congress. Then Congress adjourned.

In March 1775, representatives from each Virginia county met in a church in Richmond, Virginia. Washington and the others heard Patrick Henry’s famous speech in which he said: “Give me liberty or give me death!” But Washington’s quiet common sense impressed people as much as Henry’s dramatic words did. The representatives again elected Washington to attend the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

Elected commander in chief.

By the time Washington left Mount Vernon to attend the Second Continental Congress, the Battles of Lexington and Concord already had been fought in Massachusetts. The Congress opened on May 10, 1775. For six weeks, the delegates to the Congress debated and studied the problems facing the colonies. The majority, including Washington, wanted to avoid war. At the same time, they feared they could not avoid it.

To express his desire for action, Washington began wearing his red and blue uniform of the French and Indian War. He was appointed to one military committee after another. He was asked to prepare a defense of New York City and to study ways to obtain gunpowder. He also had to make plans for an army and to write army regulations.

Then, on June 14, Congress called on Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to send troops to aid Boston. The city had been placed under British military rule. John Adams rose to discuss the need of electing a commander in chief. In later years, Adams would be Washington’s vice president and successor as president, Adams praised Washington and said his popularity would help unite the colonies. Many New England delegates believed a northerner should be made commander in chief. But the following day Washington was elected unanimously.

Washington had not sought the position. He particularly wanted to make everyone understand he did not want the $500 monthly pay that had been voted. He said he would keep track of his expenses. He would accept nothing else for his services. His acceptance speech, on June 16, was presented with modesty.

“I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room,” Washington said, “that I this day declare with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command I am honored with.”

“First in war” (1775-1783)

“These are the times that try men’s souls,” Thomas Paine wrote during the revolution. “The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot, will in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country. …”

During the eight years of war, Washington encountered both “summer soldiers” and “sunshine patriots.” Summer soldiers did not care to fight in winter. Sunshine patriots supported the American cause only when things went well. Only his strong will to win made it possible for Washington to overcome his many discouragements.

The following sections describe the most important problems that Washington overcame to win the revolution. For an account of the main battles, see the article American Revolution.

Symbol of independence.

To most Americans of his time, Washington became the chief symbol of what they were fighting for. The colonists had been brought up to respect the British king. They did not easily accept the idea of independence. The Congress that approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, was not elected by the people, but by the legislatures of the states. And the legislatures were elected only by property owners. As a result, some people who did not own property and had no vote viewed independence with suspicion. Thousands of Loyalists, as British sympathizers were called, refused to help the fight for independence.

Although many people did not wish for independence and did not trust Congress, they came to believe in Washington. They sympathized with him for the misery he shared with his soldiers. They cheered his courage in carrying on the fight.

“Washington retreats like a General and acts like a hero,” the Pennsylvania Journal said in 1777. “Had he lived in the days of idolatry, he had been worshiped as a god.” That same year, the Marquis de Lafayette wrote to Washington: “… if you were lost for America, there is nobody who could keep the army and the Revolution for six months.”

Discouragement.

Praise did not keep Washington from feeling discouraged. Often he believed he could not hold out long enough to win. Following are several comments he wrote throughout the war.

1776—”Such is my situation that if I were to wish the bitterest curse to an enemy on this side of the grave, I should put him in my stead with my feelings. …”

1779—”… there is every appearance that the Army will infallibly disband in a fortnight.”

1781—”… it is vain to think that an Army can be kept together much longer, under such a variety of sufferings as ours has experienced.”

The army.

Throughout the war, Washington seldom commanded more than 15,000 troops at any one time. He described his soldiers as “raw militia, badly officered, and with no government.” There were two kinds of troops, soldiers of the Continental Army, organized by Congress; and militia, organized by the states.

Washington had trouble keeping soldiers in the Continental Army. At the beginning of the war, Congress let soldiers enlist for only a few months. Toward the end of the war, Washington convinced Congress that enlistments had to be longer. When their enlistments were up, the soldiers of the Continental Army went home. Sometimes a thousand soldiers marched off at once.

Washington often had to plan battles for certain dates, because if he waited longer the soldiers’ enlistments would be up. For example, Washington attacked the Hessian (German) troops at Trenton, New Jersey, on Dec. 26, 1776, for this reason. His army had shrunk to only about 5,000 troops. The enlistments of most of his soldiers would be up at the end of December. The victory at Trenton inspired many of his soldiers to reenlist.

From time to time, Washington asked the states to call out their militia to help in a battle. The militia included storekeepers, farmers, and other private citizens. They were poorly trained. Most of them did not like being called from their homes to fight. The militia complained so much that troops of the Continental Army called them “long faces.” Washington’s army was defeated many times because the militia turned and ran when they saw redcoated British soldiers.

Desertion by his soldiers was another one of Washington’s major problems. Many soldiers enlisted only to collect bonuses offered by Congress. At some times, as many men deserted each day as were enlisted. Washington authorized harsh punishment for deserters. He had some hanged. Dangerous mutinies also occurred.

“We are, during the winter, dreaming of independence and peace, without using the means to become so,” Washington wrote in 1780. “In the spring, when our recruits should be with the Army and in training, we have just discovered the necessity of calling for them, and by the fall, after a distressed, and inglorious campaign for want of them, we begin to get a few men, which come in just in time enough to eat our provisions. …”

From the time Washington took command to the end of the war, he had to put up with many incompetent officers. Congress sometimes appointed the generals without asking Washington’s advice. The states appointed the lower-ranking officers in the Continental Army and all of the militia officers. Most officers were chosen for political reasons. Some generals, such as Charles Lee and Horatio Gates, believed they should have been commander in chief. They sometimes ignored Washington’s orders. In the winter of 1777-1778, a few army officers and members of Congress hoped that Washington might be replaced by Gates. This group became known as the Conway cabal. It was named for the foreign-born general Thomas Conway, who had criticized Washington sharply. But there was no organized movement against Washington. Congress continued to support him.

Shortage of supplies.

Washington’s troops lacked food, clothing, ammunition, and other supplies throughout the war. If the British had attacked the Americans around Boston in 1775, Washington could have issued only enough gunpowder for nine shots to each soldier. He had to give up Philadelphia to the British in 1777 because he could not risk losing the few supplies he had. The army repeatedly ran out of meat and bread. Sometimes hundreds of troops had to march barefoot in the snow because they had no shoes.

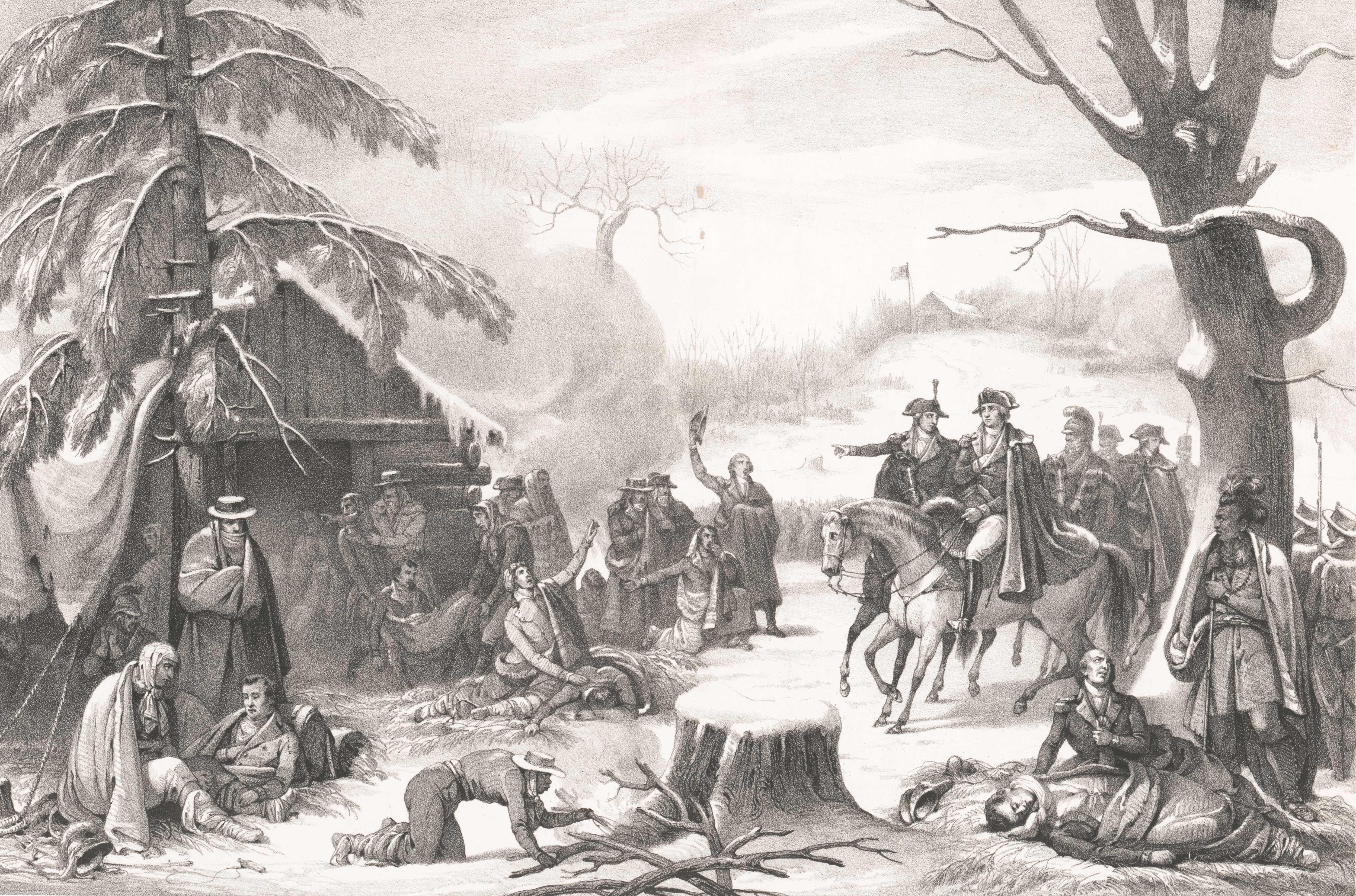

“The want of clothing, added to the misery of the season,” Washington wrote in the winter of 1777-1778 at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, “has occasioned (the soldiers) to suffer such hardships as will not be credited but by those who have been spectators.”

In the winter of 1779-1780 at Morristown, New Jersey, Major General Nathanael Greene described Washington’s army: “Poor fellows! They exhibit a picture truly distressing—more than half naked and two thirds starved. A country overflowing with plenty are now suffering an Army, employed for the defense of everything that is dear and valuable, to perish for want of food.”

Winning the war.

From the beginning of the war, Washington knew the powerful British Navy gave the enemy a great advantage. The ships of the British could carry their army anywhere along the American coast. Washington’s tiny, ragged army could not possibly defend every American port.

On the other hand, Washington knew from his experience in the French and Indian War that the British army moved slowly on land. He also knew it could be beaten. He proved that he could stay one jump ahead of the British by quick retreats. Meanwhile, Washington waited and prayed for the French to send warships to America. He hoped then to trap the British while the French navy prevented them from escaping.

Washington’s prayers came true at Yorktown, Virginia. There, on Sept. 28, 1781, he surrounded Lord Cornwallis’s army. The French fleet prevented the British from escaping by ship. Washington began attacking on October 6. On October 19, Cornwallis and 8,000 troops surrendered.

Turning down a crown.

After Cornwallis surrendered, the British lost interest in the war. Peace talks dragged on in Paris for many months.

In May 1782, Colonel Lewis Nicola sent a document to Washington on behalf of his officers. It complained of injustices the army had suffered from Congress. It suggested that the army set up a monarchy with Washington as king. Washington replied that he read the idea “with abhorrence.” He ordered Nicola to “banish these thoughts from your mind.”

In November 1783, word finally arrived that the Treaty of Paris had been signed two months earlier. The last British soldiers boarded ships at New York City on November 25. That same day, Washington led his troops into the city. About a week later, on December 4, he said good-by to his officers at Fraunces Tavern. On his way home to Virginia, he stopped at Annapolis, Maryland, where Congress was meeting. He returned his commission as commander in chief, saying “… I resign with satisfaction the appointment I accepted with diffidence.”

“First in peace” (1784-1789)

Washington was now 51 years old. He reached Mount Vernon in time to spend Christmas 1783 with Martha. The war had aged him. He now wore glasses. As he had told his officers: “I have grown gray in your service and now find myself growing blind.”

For the next five years, Washington lived the life of a Virginia planter. Many guests and visitors dropped in at Mount Vernon. His entertainment expenses were large. In 1787, he wrote: “My estate for the last eleven years has not been able to make both ends meet.”

Washington believed in the future development of the West. This made him search for more land to buy. In 1784, he made a 680-mile (1,090-kilometer) trip on horseback through the wilderness to visit his land holdings southwest of Pittsburgh. He helped promote two companies interested in building canals along the Potomac and James rivers. He took part in plans to drain the Dismal Swamp in southern Virginia.

Washington also widened his interest in farming. In many ways his farm methods were ahead of the times. He began breeding mules. He introduced rotation of crops to his farms. He began using waste materials from his fishing industry as fertilizer. He also took steps to prevent soil erosion.

Constitutional Convention.

In 1786, Washington wrote: “We are fast verging to anarchy and confusion.” In Massachusetts, open revolt broke out. See Shays’s Rebellion. Finally, the states agreed to call a meeting in 1787 to consider revising the weak Articles of Confederation. Washington was elected unanimously to head the Virginia delegates. A huge welcome greeted him when he arrived in Philadelphia in May. All the bells in the city were rung. The Constitutional Convention opened on May 25. The delegates elected Washington president of the convention.

Debate on the proposed constitution went on throughout the hot summer. Washington wrote: “I see no end to my staying here. To please all is impossible….” As president, Washington took little part in the debates. But he helped hold the convention together. The convention finally reached agreement in September. See Constitution of the United States.

Elected president.

By the summer of 1788, enough states had approved the Constitution to allow for the reorganization of the government. Throughout the country, people linked Washington’s name directly to the new Constitution. They took it for granted that he would be chosen as the first president. But Washington had doubts as to whether he should accept the position. He wrote: “… If I should receive the appointment, and if I should be prevailed upon to accept it, the acceptance would be attended with more diffidence and reluctance than I ever experienced before in my life.”

In February 1789, members of the first Electoral College met in their own states and voted. Each elector voted for two candidates. The candidate who received the most votes became president. The runner-up became vice president. Washington was elected president with a total of 69 votes—the largest number possible—from the 69 electors. John Adams was elected vice president with 34 votes.

First administration (1789-1793)

Washington’s journey from Mount Vernon to New York City was the parade of a national hero. Every town and city along the way held a celebration.

Inauguration Day

was April 30, 1789. The 57-year-old Washington rode in a cream-colored coach to Federal Hall at Broad and Wall streets. Washington walked upstairs to the Senate Chamber, then out onto a balcony. Thousands watched as Washington raised his right hand and placed his left hand on an open Bible. Solemnly he repeated the presidential oath of office given by Robert R. Livingston of New York. Washington added the words, “So help me God!” and kissed the Bible. Cannons fired a 13-gun salute. Then President Washington walked back to the Senate Chamber and delivered his inaugural address.

Life in the Executive Mansion.

The house of Samuel Osgood on Cherry Street in New York City was the first Executive Mansion. In February 1790, Washington moved to a larger house on Broadway. When Congress later made Philadelphia the capital, the Washingtons moved into the home there of financier Robert Morris. It was the finest house in the city.

The Washingtons entertained a great deal. They had a large staff of servants and slaves. The president held two afternoon receptions each week so he could meet the hundreds of people who wanted to see him. Every Friday night, Martha Washington held a formal reception. These affairs ended at 9 p.m. because, she said, the president “always retires at 9 in the evening.” Each year on his birthday, Washington gave a ball. The dancing at the ball lasted until well after midnight.

Martha Washington’s two young grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis, came to live with the Washingtons in the early 1780’s. Their father, John Custis, had died during the revolution. Their mother had remarried.

Martha Washington was described in a letter by Abigail Adams, wife of the vice president: “She is plain in her dress, but that plainness is the best of every article. … Her hair is white, her teeth beautiful, her person rather short. … Her manners are modest and unassuming, dignified and feminine. …”

The Washingtons made many trips home to Mount Vernon during the next eight years. The president sometimes stayed there as long as three months when Congress was not in session.

New precedents of government.

“I walk on untrodden ground,” Washington said as he began the new responsibilities of his office. “There is scarcely any part of my conduct that may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.”

Washington believed that the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the government should be separate. The Constitution provided for such separation. He thought the president should not try to influence the kinds of laws that Congress passed. However, he believed that if he disapproved of a bill, he should let Congress know by vetoing it. Washington regarded the duties of his office largely as administering the laws of Congress and supervising relations with other countries.

In 1789, at the beginning of Washington’s presidency, 11 of the original 13 colonies had ratified the Constitution. North Carolina accepted the Constitution in November 1789. Rhode Island did so in 1790. Three other states joined the Union while Washington was in office. Vermont joined in 1791. Kentucky became a state in 1792. Tennessee joined in 1796.

On July 4, 1789, Washington received the first important bill passed by the new Congress. It provided income to run the government by setting taxes on imports. He signed it with no comment.

By September, Congress had established three executive departments to help run the government. They were the Department of Foreign Affairs (now Department of State), the Department of War, and the Department of the Treasury. Congress provided for an attorney general and a continuation of the Post Office. Congress also adopted the Bill of Rights and established a system of federal courts.

Cabinet.

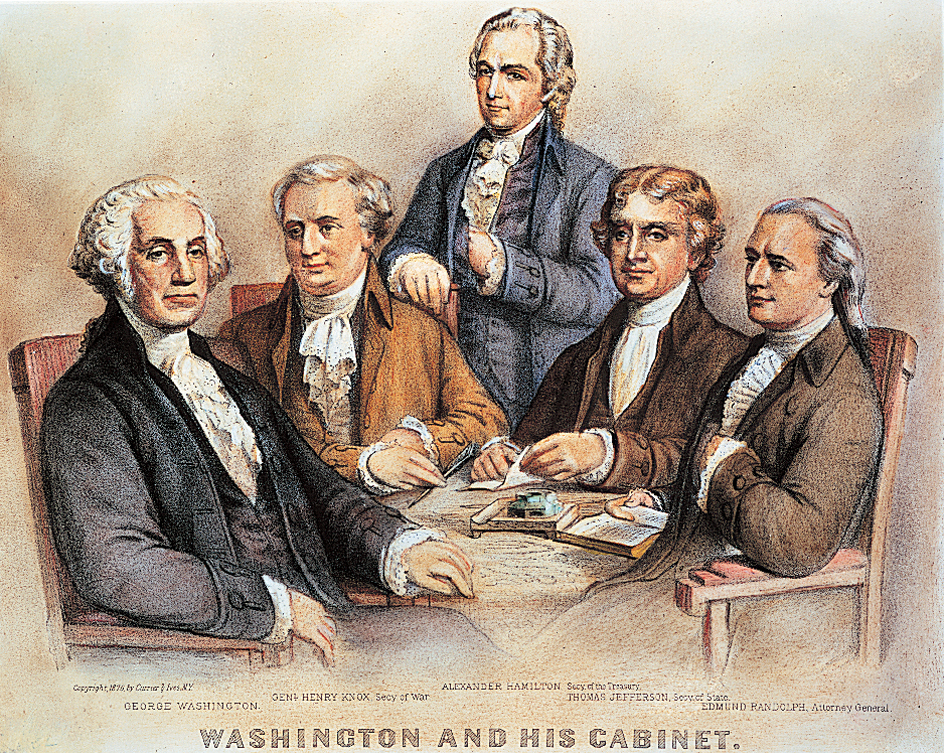

In September, Washington began making important appointments. He chose men whom he knew and could trust:

Chief justice of the United States— John Jay, who had been secretary of foreign affairs under the Articles of Confederation.

Secretary of state—Thomas Jefferson, who had served with Washington in Virginia’s legislature.

Secretary of war— Henry Knox, Washington’s chief of artillery during the revolution.

Secretary of the treasury— Alexander Hamilton, who had been one of Washington’s military aides.

Attorney general— Edmund Randolph, former governor of Virginia and a member of the Constitutional Convention. He had been Washington’s friend for many years.

During his first administration, Washington relied on the advice of Hamilton and James Madison, a congressman from Virginia. At first, Washington did not call his department heads together as a group. Instead, he asked them to give him written opinions or to talk with him individually. Washington allowed his department heads to act independently. He did not try to prevent Hamilton, Jefferson, or the others from influencing Congress. Toward the end of his first administration, he began calling the group together for meetings. In 1793, Madison first used the term cabinet to refer to the group.

Finances.

Washington’s new government had millions of dollars in debts. The Congress of the Articles of Confederation had been unable to pay the debts. Hamilton drew up a plan to straighten out the finances. There was much argument. But finally the plan passed in July 1790. The law provided that the national government would assume the wartime debts of the states. It also called for borrowing $12 million from other countries and for paying interest on the public debts.

New national capital.

Congress approved a bill in July to transfer the government to Philadelphia until 1800. After that, the capital would be moved to a federal district on the Potomac River. The president took up residence in Philadelphia in November 1790. During the next several years, Washington devoted much time to the plans for the new national capital, which came to bear his name.

Constitutional debate.

Hamilton obtained passage in 1791 of a bill setting up the First Bank of the United States. Washington had to decide whether the government had powers under the Constitution to charter such a corporation. Jefferson and Randolph believed that the bill was unconstitutional. They said such powers were not mentioned in the Constitution. Hamilton argued that the government could use all powers except those denied by the Constitution. Washington, who believed in a strong national government, took the side of Hamilton. He signed the law.

First veto

by Washington of congressional legislation was made in April 1792. The first census of the United States had shown that the population was 3,929,214, including 697,000 slaves. Congress then passed a bill in March to raise the number of U.S. representatives from 67 to 120. Washington believed the bill was unconstitutional. He objected to it because some states would have greater representation in proportion to population than other states. Many people thought the bill favored Northern States over Southern States. Congress failed to override Washington’s veto. The lawmakers then revised the bill to provide for a House of 103 members.

Rise of political parties.

Washington was disturbed as he saw that Jefferson and Hamilton were disagreeing more with each other. Voters and newspapers who supported Hamilton’s views of a stronger national government called themselves Federalists. The Federalists became the party of the Northern States. They also represented banking and manufacturing interests. Those who favored Jefferson’s ideas of a strict interpretation of the Constitution in defending states’ rights became known as Anti-Federalists. They were also called Democratic-Republicans. The Democratic-Republicans mainly represented the Southern States and the farmers.

Washington attempted to favor neither party. He tried to bring Hamilton and Jefferson into agreement. He also tried to discourage the growth of political parties.

Reelection.

In 1792, Washington began to make plans for retirement. In May, he asked Madison to help him prepare a farewell address. Madison did so. But he urged Washington to accept reelection as president. Hamilton, Knox, Jefferson, and Randolph each asked Washington to continue as president. One of the strongest arguments came from Jefferson. He wrote: “Your being at the helm will be more than an answer to every argument which can be used to alarm and lead the people in any quarter into violence or secession. North and South will hang together if they have you to hang on.”

Members of the Electoral College cast their votes in December 1792. Their ballots were counted on Feb. 13, 1793. Washington again was elected president with the largest number of votes possible—132. Adams received 77 votes. He was again the runner-up and vice president.

Second administration (1793-1797)

Washington’s second inauguration took place in Congress Hall in Philadelphia on March 4, 1793. The 61-year-old Washington faced greater problems during his second administration than during his first.

Neutrality proclamation.

Word came in April 1793 that a general war had begun in Europe. Britain, Spain, Austria, and Prussia were all fighting against the new French republic. Although the United States had signed an alliance with the French king in 1778, Washington wanted to “maintain a strict neutrality.” Jefferson favored the recent French Revolution. He did not want to issue a neutrality statement. Hamilton believed neutrality was necessary.

Washington ordered Attorney General Randolph to write up a statement. On April 22, the president signed the Neutrality Proclamation. It called for “conduct friendly and impartial” to all the warring nations. It also forbade American ships from carrying war supplies to the fighting countries.

Relations with France.

The United States decision to stay out of the European war pleased the British. But it angered the French. Leaders of the French Revolution believed the United States should stand by its alliance of 1778 with King Louis XVI. But the revolutionaries had beheaded the king who made the alliance. This posed a delicate point in international law. Washington had no precedents to guide him. He finally decided to be cool and formal in receiving Edmond Genet, the new minister appointed by the French republic.

Genet seemed determined to draw Americans into the war on the side of France. He tried secretly to win Democratic-Republicans to the French cause during the spring and summer of 1793. This attempt upset Washington. The president’s patience gave out when Genet tried to outfit warships in American ports and send them to sea against the British.

After a stormy Cabinet meeting in July 1793, Washington asked France to recall Genet. Washington said that the French minister endangered American neutrality. Genet was stripped of his power. But he was allowed to stay in the United States. The neutrality crisis of 1793 passed. The United States remained at peace.

Whiskey Rebellion.

In 1794, Washington proved that the government could enforce federal laws in the states. Farmers in four counties in western Pennsylvania had refused to pay federal taxes on manufacturing whiskey. They armed themselves and attacked federal officials. Washington raised nearly 13,000 troops and sent them to western Pennsylvania. By November 1794, the rebellion had been crushed. The ringleaders were arrested.

Relations with Britain.

Washington worried as relations with Britain grew worse. British warships stopped American ships carrying food supplies to France and seized their cargoes. They sometimes took sailors off the American ships and forced them into the British Navy. British troops refused to give up western frontier forts they were supposed to have surrendered under terms of the treaty of 1783. The British also were stirring up Indian fighting on the western frontier. In an effort to settle problems with Britain, Washington sent Chief Justice John Jay to London in 1794.

In March 1795, Washington received a copy of a treaty Jay had signed on Nov. 19, 1794. Earlier copies had been lost in the mail. Most of the treaty had to do with regulation of trade between America and Britain. It also called for British troops to give up the frontier forts in 1796. But it contained no agreement that British ships would stop waylaying American ships and taking sailors.

Washington called a special session of the Senate in June to study the treaty. Federalists supported the Jay Treaty because it insured continuing trade with Britain. The Democratic-Republicans opposed the treaty because they believed it would harm France. The Federalists controlled the Senate. As a result, the treaty was ratified by a vote of 20 to 10, except for one section. This section opened to United States ships trade with the British West Indies, a group of Caribbean islands under British control, but it also severely restricted this trade. Washington could not make up his mind whether or not to sign the treaty. He went home to Mount Vernon to think about it.

At Mount Vernon, the president received word of riots in many cities protesting the Jay Treaty. A mob in New York City stoned Hamilton. A Philadelphia mob broke windows at the British embassy.

Cabinet scandal.

Washington returned to Philadelphia on Aug. 11, 1795. He learned that the British had captured a French diplomatic message. The message seemed to indicate that Edmund Randolph, the secretary of state, was a traitor. Washington read a translation of the French message. He believed that Randolph might have sold secrets to the French.

Without saying anything to Randolph about his suspicions, Washington called a Cabinet meeting to discuss the Jay Treaty. At the meeting, Randolph argued against signing the treaty as long as Britain continued to seize American ships. Washington became convinced Randolph was in the pay of France. Washington signed the treaty.

As soon as the Jay Treaty had been delivered to the British Embassy, Washington called in Randolph and showed him the French message. Randolph denied his guilt, but resigned. He swore he would prove his innocence. Randolph later wrote a book in which he declared that he had never betrayed his country.

Washington now suffered the bitterest criticism of his career. He was accused by Democratic-Republican newspapers of falling victim to a Federalist plot in signing the Jay Treaty. It was even suggested that he should be impeached because he had overdrawn his $25,000 salary. Washington’s feelings were hurt.

Public opinion of Washington began to improve when he announced a few months later that a treaty had been negotiated with Spain opening up the Mississippi River to trade. Agreement also had been reached with the Barbary States to release American prisoners and to let American ships alone. The Barbary States were to receive a payment of $800,000 ransom, plus $24,000 tribute each year. Sea raiders licensed by these states were attacking U.S. and other ships in the Mediterranean Sea. Peace treaties also had been signed with Indian tribes on the frontier.

Farewell Address.

Washington believed the office of president should be above political attack. He had become tired of public office. The new House of Representatives had a large Democratic-Republican majority and was unfriendly to Washington. He also felt himself growing old.

In May 1796, Washington dusted off the draft of his Farewell Address that he and James Madison had worked on four years earlier. He sent it to Jay and to Hamilton for their suggestions. Finally, in September, the much-edited address, all in Washington’s handwriting, was ready. He gave it to the editor of the American Daily Advertiser, a Philadelphia newspaper. The paper published it on September 19.

In the election campaign that followed, Washington favored John Adams, the Federalist candidate for president. But Washington did not take an active part in the campaigning. The Democratic-Republican candidate was Thomas Jefferson. When the Electoral College met, it gave 71 votes to Adams and 68 to Jefferson. Under the existing constitutional provision, Adams became president and Jefferson vice president.

At the inauguration in March 1797, Adams sensed Washington’s relief at retirement. Adams wrote to his wife: “He seemed to me to enjoy a triumph over me. Methought I heard him say, “Ay! I am fairly out and you fairly in! See which of us will be the happiest!'”

“First in the hearts of his countrymen” (1797-1799)

Washington was 65. He happily went home to Mount Vernon. Friends said he looked even older. But he did not lose touch with public affairs. Almost every day visitors dropped in to see him. On July 31, 1797, he wrote: “Unless someone pops in unexpectedly—Mrs. Washington and myself will do what has not been done within the last twenty years by us—that is to set down to dinner by ourselves.” He described his daily routine in a letter:

“I begin … with the sun … if my hirelings are not in their places at that time I send them messages expressive of my sorrow for their indisposition … breakfast (a little after seven o’clock …). This over, I mount my horse and ride round the farms … The usual time of sitting at table; a walk, and tea, brings me within the dawn of candlelight … I resolve that … I will retire to my writing table and acknowledge the letters I have received; but when the lights are brought, I feel tired, and disinclined to engage in this work.”

Several farms made up the more than 7,600 acres (3,075 hectares) of Mount Vernon. Managing them took much of Washington’s time. He made frequent trips to watch construction in the new city of Washington, D.C. It then was called the Federal City.

Recall to duty.

While Washington enjoyed his retirement, relations between the United States and France grew worse. The government decided to raise an army for defense. President Adams asked Washington’s help. On July 4, 1798, Washington was commissioned as “Lieutenant General and Commander in Chief of the armies raised or to be raised.”

Washington went to Philadelphia for a few weeks in November to help plan the new army. He had dinner one night in debtors’ prison with financier Robert Morris. Washington had lived in Morris’s Philadelphia home while president. Morris had gone to prison because he could not pay his debts.

During his last year of life, Washington wrote many letters to the generals he chose for the new army. Federalist leaders asked if he would consider running for a third term as president. He said no. Washington also was saddened by the deaths of friends and relatives. Patrick Henry died on June 6, 1799. Washington’s last living brother, Charles Washington, died on Sept. 20, 1799.

Death.

On December 12, Washington wrote his last letter. It was to Alexander Hamilton. In it he discussed the importance of establishing a national military academy. After finishing the letter, Washington went for his daily horseback ride around Mount Vernon. The day was cold. Snow turned into rain and sleet. Washington returned after about five hours and sat down to dinner without changing his damp clothes. The next day, he awoke with a sore throat. He went for a walk. Then he made his last entry in his diary, noting down the weather: “Morning Snowing & abt. 3 Inches deep … Mer. 28 at Night.” These were his last written words.

Between 2 and 3 a.m. on Dec. 14, 1799, Washington awakened Martha. He had difficulty speaking and was ill. But he would not let her send for a doctor until dawn. James Craik hurried to Mount Vernon. Craik had been his friend and doctor since he was a young man. By the time Craik arrived, Washington already had called in an overseer and had about a cup of blood drained from his veins. Craik examined Washington and said the illness was “inflammatory quinsy.” Craik bled Washington again. Present-day doctors believe the illness was a streptococcal infection of the throat.

Two more doctors arrived in the afternoon. Again Washington was bled. Late in the afternoon, he could hardly speak. He told the doctors: “You had better not take any more trouble about me; but let me go off quietly; I cannot last long.”

About 10 p.m. on December 14, Washington whispered: “I am just going. Have me decently buried, and do not let my body be put in the vault in less than two days after I am dead. Do you understand me?” His secretary answered: “Yes, sir.” Washington said: “‘Tis well.” He felt for his own pulse. Then he died.

On December 18, Washington was given a military funeral. His body was laid to rest in the family tomb at Mount Vernon. Throughout the world, people were saddened by his death. In the United States, thousands of people wore mourning clothes for months.

No other American has been honored more than Washington. The nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., was named for him. There, the giant Washington Monument stands. The state of Washington is the only state named after a president. Many counties, cities, towns, streets, bridges, lakes, parks, and schools bear his name. Washington’s portrait appears on the $1 bill and on the quarter. He has appeared on more U.S. postage stamps than any other person.

After the siege of Boston in 1776, the Massachusetts legislature in a resolution had said: “… may future generations, in the peaceful enjoyment of that freedom, the exercise of which your sword shall have established, raise the richest and most lasting monuments to the name of Washington.” The legislators foresaw the place he would hold forever in the hearts of Americans.

At his death, Washington held the title of lieutenant general. It was then the highest U.S. military rank. But through the years, he was outranked by many U.S. Army officers. In 1976, Congress granted Washington the nation’s highest military title, General of the Armies of the United States. This action confirmed him as the senior general officer on the Army rolls.