Weaving is the process of making fabric by interlacing two sets of yarns over and under one other on a machine called a loom. Yarns are fibers that have been spun into strands. Weavers use yarns made of natural fibers such as wool, silk, cotton, and linen. They also use manufactured fibers including rayon, nylon, polyester, and acrylic. Strips of other materials, such as metal, leather, and wood, can also be woven. Woven fabrics can be a single solid color or intricately patterned. They can be lightweight or they can be thick and heavy.

True weaving involves the use of a loom. A loom is a machine that helps the weaver to interlace the yarns. People make such objects as baskets and mats by interlacing grasses, strips of wood, or the woody stems of plants. This is done without the use of a loom. Braids are made from one set of yarns interlaced by hand. Archaeologists have found evidence of such hand interlacing, including braiding and basketry, that dates to the Paleolithic era more than 25,000 years ago.

A loom can be as small and simple as a few sticks and some string, or as large as a room and so complex that several highly-trained people are needed to work them. To use a loom, the weaver stretches the first set of yarns, called the warp, vertically onto the loom. The loom holds the warp tight and keeps it separated into groups. This allows the weaver to interlace the second set of yarns, called the weft, crosswise through the warp. The weft is sometimes called the woof or the filling.

Weaving ranks as a major industry in many countries. Weaving is also a popular craft. Artists exhibit and sell decorative woven items at art fairs, galleries, and museums. Many people design and weave colorful fabrics as a hobby. The term textile has traditionally meant a woven fabric. The term comes from the Latin word texere, meaning to weave. Today, textile refers to any product that is woven, knitted, braided, or otherwise constructed of fibers.

Types of weaves

Weavers use three basic types of weaves: plain weave, twill weave, and satin weave. These weaves can be varied to create many different kinds of woven fabrics.

Plain weave

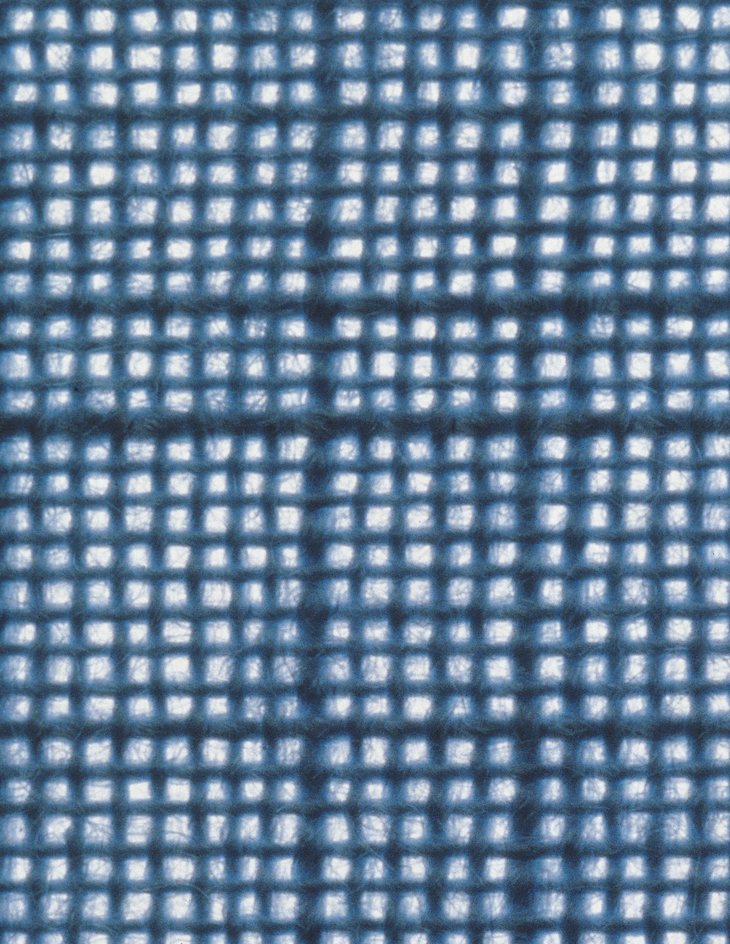

(also called tabby weave) is the simplest and most common type of weave. In a plain weave, both the warp and weft yarns go over one yarn of the opposite set and then under the next one. This is similar to the weave that is used to make baskets. Every weaving culture uses this simple weave. Weavers can make a skip in the pattern by passing weft yarns over two or more of the warp yarns. This creates a patch of passed-over threads called a float. Weavers can add floats to a plain weave to create different patterns and textures. Muslin, gingham, percale, and taffeta are all plain-woven fabrics.

Twill weave

produces raised diagonal lines in the fabric. Each weft thread crosses two, three, or four warp yarns at a time, creating a pattern of floats. The floats are shifted by one warp yarn in each row of the weft. This shift makes a diagonal line in the pattern. Weavers can create diamond shapes and zigzags by changing the direction of the diagonal lines. Twill weave creates sturdy fabrics such as denim, gabardine, and serge.

Satin weave

uses long floats to make shiny, smooth fabrics. Warp yarns pass over four or more weft yarns and then pass under just one weft yarn. Satin fabrics are often used for formal clothing and furnishings.

Other weaves.

Plain weave, twill weave, and satin weave can be altered in many ways. Variations of these patterns produce a wide range of weaves. Each variation creates unique patterns and textures in the finished fabric. In gauze weave, for example, the warp yarns cross one another around the weft yarns. This creates an open, sheer texture. Gauze fabrics are popular for sheer curtains.

In tapestry weave, the weaver interlaces many separate weft yarns across a single row to create a pattern. Instead of passing all the way across the fabric, a weft yarn interlaces only across the area where it is needed for the pattern, passing back and forth across only those warp yarns. This weave makes it possible for weavers to create detailed scenes in fabrics. This technique is used to create the scenes featured in some large tapestry wall hangings.

Damask weave uses contrasting areas of warp and weft floats to create a pattern out of shiny and matte (dull-surfaced) textures. This creates a faint pattern, usually in fabrics of a single color. Damask is a popular weave for curtains and tablecloths.

Brocade weave (also called supplementary weave) uses extra weft or warp yarns to weave a pattern in the ground fabric (the existing fabric upon which a design is created). The extra yarns can be pulled out of the ground fabric. This supplementary weft patterning is an ancient technique used in many weaving traditions around the world. Brocade designs are woven by hand or by machine into cloth to make fabrics for bedspreads, draperies, furniture coverings, and dresses. It became a favorite material for the clothing of European royalty and nobility in the 1800’s. Ribbons are also often patterned with brocade.

Pile weave is another type of supplementary weave, like brocade. In a pile weave, the extra set of yarns sticks up from the surface of the fabric, creating a fuzzy texture. Velvet, terrycloth towels, and most rugs and carpets are pile-woven.

In double weave, two separate fabrics are woven at once. The fabrics interlace with each other to create patterns or extra thickness and strength. Double weave fabrics are often used for blankets and coats.

Jacquard weave can only be created on a special device called a Jacquard loom. This weave is used to make elaborate patterns. A Jacquard loom can move every warp yarn individually, so almost any pattern can be woven into the fabric. Industrial weavers use Jacquard weaving to quickly and cheaply create imitations of tapestry, brocade, and other complex and expensive hand weaves. Jacquard weaves are often used for upholstery, curtains, and clothing.

After any textile comes off the loom, it can be further decorated with embroidery or printing. It can also be sewn into clothing, home furnishings, or bags.

Weaving on a loom

How a loom works.

To weave fabric on a loom, the weaver first stretches the warp yarns between two rods or beams. The weaver then pulls the warp yarns through the shedding device. This can be a bar, frame, or string with openings called heddles that hold the warp yarns. The shedding device allows the weaver to move the warp yarns. In order for the woven cloth to hold together, a loom must have at least two shedding devices with separate groups of warp yarns attached. The weaver weaves by moving a shedding device to separate the warp yarns, and then passing the weft yarn through them.

Kinds of looms.

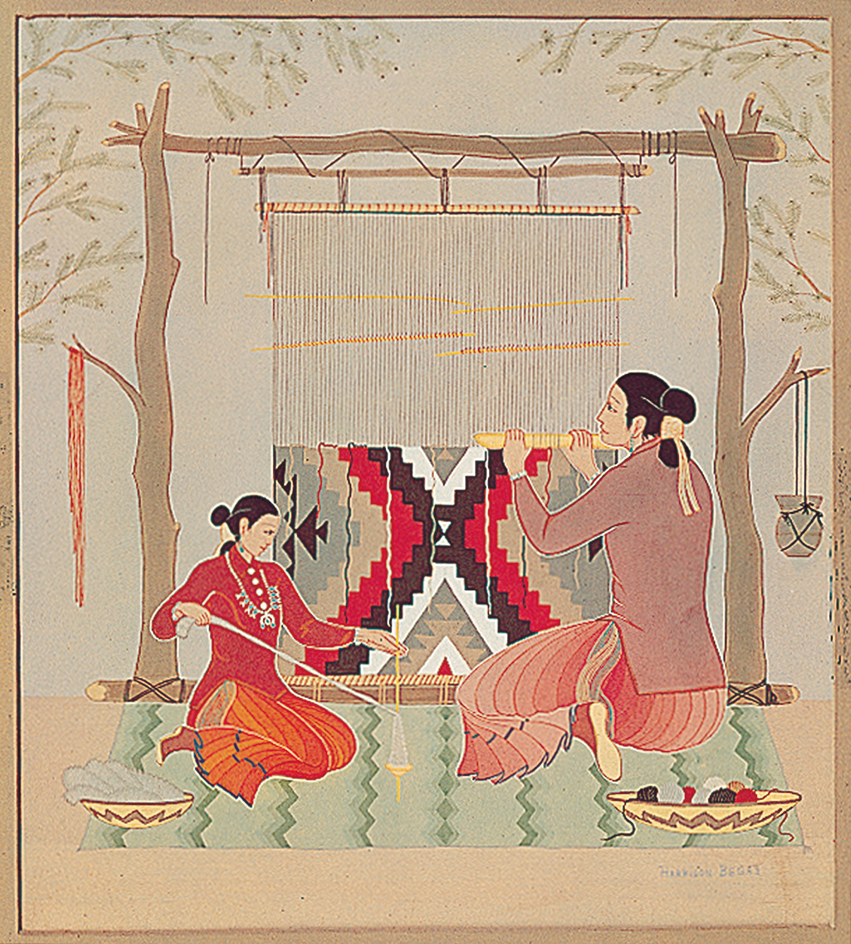

There are several basic types of looms. In a backstrap loom, a strap on one end of the loom wraps around the weaver’s back. The weaver attaches the other end to a sturdy object such as a tree and leans or sits back to pull the warp tight. Tapestry looms are usually vertical frames with horizontal bars that serve as shedding devices. On a treadle loom, the weaver operates a foot pedal to move the shedding device, freeing their hands from that task. The treadle loom weaves more quickly than a backstrap or tapestry loom. Drawlooms and Jacquard looms can weave large and complex patterns by moving every warp yarn individually. Power looms move the shedding devices and pass the weft yarns automatically, without a weaver.

History

Earliest weaving.

Unlike stone, metal, and ceramic objects, prehistoric baskets and fabrics rot away over time. Yet scholars know that since the Stone Age, all human societies have made baskets and bags to carry and store food. They also made braided necklaces and other garments. Ceramic figurines of women made in Europe around 25,000 years ago, known as Venus figurines, sometimes feature interlaced hats, belts, and fringed skirts. Such clues indicate that braiding and other hand interlacing techniques probably extend even farther back in human prehistory. However, it is difficult for archaeologists to determine exactly when humans began making textiles and fabrics.

True weaving.

Evidence from archaeology shows that true weaving with a loom began at least 8,000 years ago in Mesopotamia. Early weavers used yarns made from flax and wool from sheep and goats. Shreds of simple linen cloth, made from fibers of the flax plant, have been found at prehistoric sites in Turkey. From there, the art of weaving spread to many countries. Ancient Egyptians were famed for their fine, sheer linen fabrics. In ancient Greece and Persia, beautiful multicolored fabrics were woven from wool. Ancient weavers made fine cotton fabrics as early as 5,000 years ago in the Indus River Valley region, in what are now Pakistan and western India. By about 1500 B.C., the region was exporting cotton fabrics to Mesopotamia.

In China, weaving began independently at least 4,000 years ago. It then spread to Japan and Southeast Asia. Ancient Chinese people domesticated silk. They probably also invented the drawloom for weaving elaborate patterns into fabrics. Colorful, shiny, and intricately patterned Chinese silks were highly valuable. They were traded all over Asia and Europe as early as about 300 BC. Ramie, a plant grown for fiber, and cotton were also woven in Asia.

Weaving was also invented independently in South America more than 4,000 years ago. It spread from ancient Peru to what are today Mexico and the American Southwest. In Peru, weavers used cotton and alpaca fibers to create extremely elaborate and eye-catching patterns. They used these fabrics to make multicolored tunics, gauzy scarves, and other garments.

Weaving became a major industry in Europe in the 1100’s. Special workshops in northern France and the Netherlands wove elaborate wool tapestry wall hangings depicting historical and religious scenes, as well as decorative motifs. Italy specialized in luxurious silk damasks and velvets. These were often embellished with gold or silver thread for elite clothing and bed hangings. The finest linen fabrics came from the Netherlands, including fine lawn (smooth, lightweight fabric) for undergarments and damasks for tablecloths.

The Industrial Revolution

began in Britain in the 1700’s. Weaving was the first art form to be industrialized. In 1733, the English inventor John Kay invented the fly shuttle, a device that automatically threads the weft through the warp. The English clergyman Edmund Cartwright invented the steam-powered loom in 1785, and the French weaver and merchant Joseph Marie Jacquard invented the Jacquard loom in 1804. These inventions, along with spinning and printing machines, allowed weavers to create woven fabric about 200 times faster than they could at a handloom. New factories churned out millions of yards of mostly cotton fabric. They also wove wool, linen, and silk. Fabrics became much cheaper to purchase. By the 1800’s, weaving factories were operating in many European countries, as well as in the United States.

Today, most fabrics bought at stores worldwide are factory-woven on power looms. Most weaving factories are in Asia and Russia. Modern power looms use air jets to shoot weft yarns through the warp yarns at up to 60 miles per hour (95 kilometers per hour). Over 35 million tons (30 million metric tons) of woven fabric are produced each year.

Hand weaving remains very popular around the world. Artists create wall hangings and even sculptures using tapestry and other weaves. Many people enjoy weaving as a hobby, creating such objects as placemats, blankets, and shawls on hand looms. Weavers in many countries create distinctive and beautiful fabrics as a way of continuing their cultural traditions.