Western frontier life in America describes one of the most exciting periods in the history of the United States. From 1850 to 1900, swift and widespread changes transformed the American West. At the beginning of that period, a great variety of Indigenous (native) American cultures dominated most parts of the region. By the end of the era, the West had become a bustling society populated by new immigrants of all kinds.

Historians sometimes define the American West as lands west of the 98th meridian, or 98° west longitude. This line of longitude runs though the middle of Texas and Kansas up through the eastern third of Nebraska and the Dakotas. Some definitions of the region include all lands west of the Mississippi or Missouri rivers. For the complete story of western expansion in the United States, see Westward movement in America.

Regardless of the precise boundary line used, the western frontier differed in many ways from the eastern United States. Much of the West had a drier climate than that of the East, and western terrain often proved much harsher. As a result, immigrants to the West had to adapt and find new ways of doing things to survive. Their efforts were aided by improvements in transportation, communication, farm equipment, and other areas.

This article will first describe the great changes experienced on the western frontier and the different peoples who inhabited that frontier. It will then focus on three major economic activities that transformed the region: mining, ranching, and farming. The article will also look at conflicts between Indigenous Americans and white settlers. Finally, it will examine the ways in which the West left its mark on American culture.

The shifting frontier

The frontier moves west.

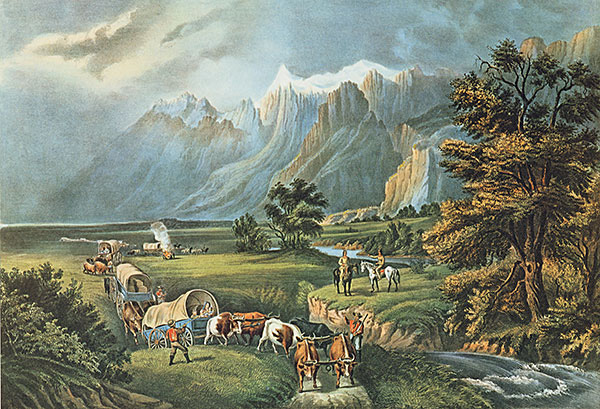

Throughout the 1800’s, America’s frontier moved steadily westward. Yet in the 1840’s, immigrants to the West saw most of the region as an obstacle, not a destination. They feared the area’s vast deserts and rugged mountain ranges. Many Indigenous tribes—then commonly known as Indians—occupied these areas. Immigrant farmers initially skipped over most of the West, migrating instead to fertile valleys in California and Oregon by a variety of land and sea routes.

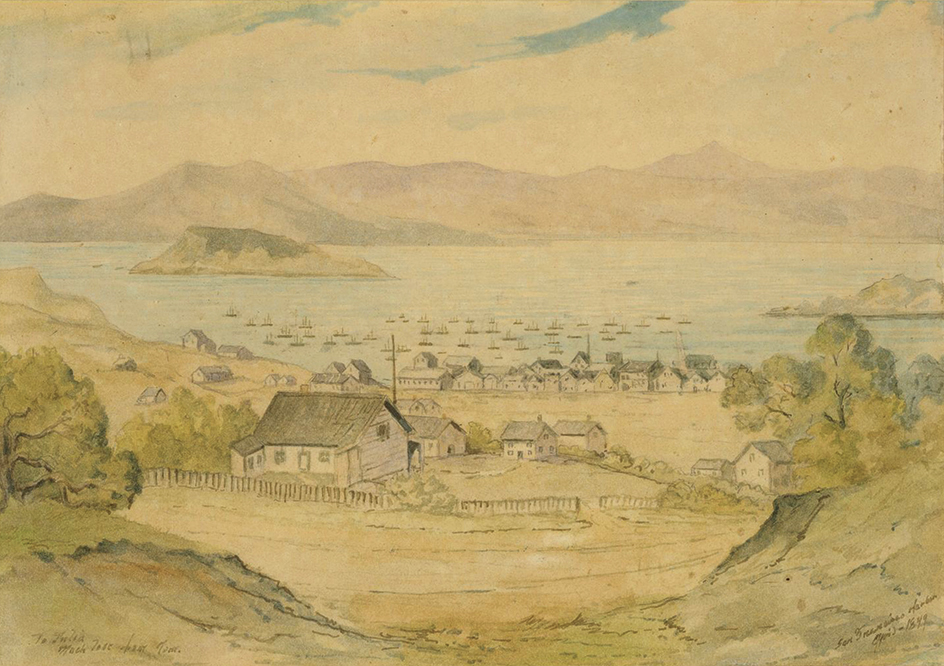

Two events helped spur a much larger migration by 1849. First, the U.S. victory in the Mexican War (1846-1848) gave the young nation vast new areas of land in the West. Second, a gold rush in California in 1849 attracted droves of American fortune seekers called “Forty-Niners.” The gold rush also attracted Chinese, Europeans, South Americans, and others, all hoping to strike it rich.

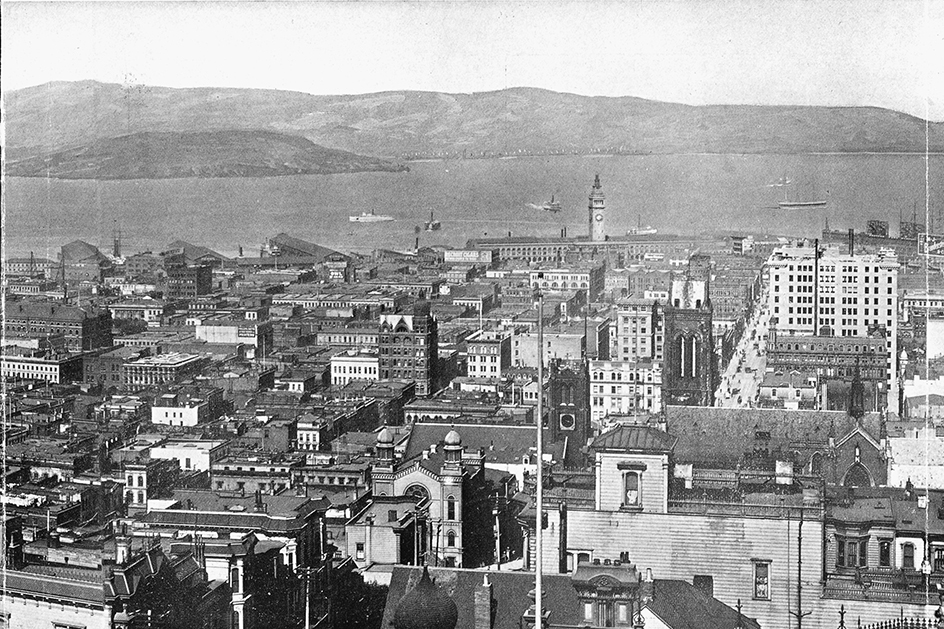

Later discoveries of rich ore deposits spurred new migrations to a variety of places, including Pikes Peak in Colorado, the Comstock Lode in Nevada, and the Black Hills of South Dakota. In each instance, the local population soared, as miners poured in and people engaged in supplying the miners’ many needs flocked to the latest boom towns. Miners required food, equipment, clothing, services, and entertainment, so businesses competed to provide them. Miners needed pack animals as well as meat, so ranchers also benefited. For example, some ambitious Oregonians drove cattle south to the California gold mines.

Improvements in transportation.

As more Americans pushed westward, new technologies assisted them. Before the 1850’s, most people traveled westward by boat or wagon. These methods proved slow and expensive, and they provided limited access to western lands. The railroad, or “iron horse,” became a vital new travel option, especially after the 1860’s. See Railroad (History).

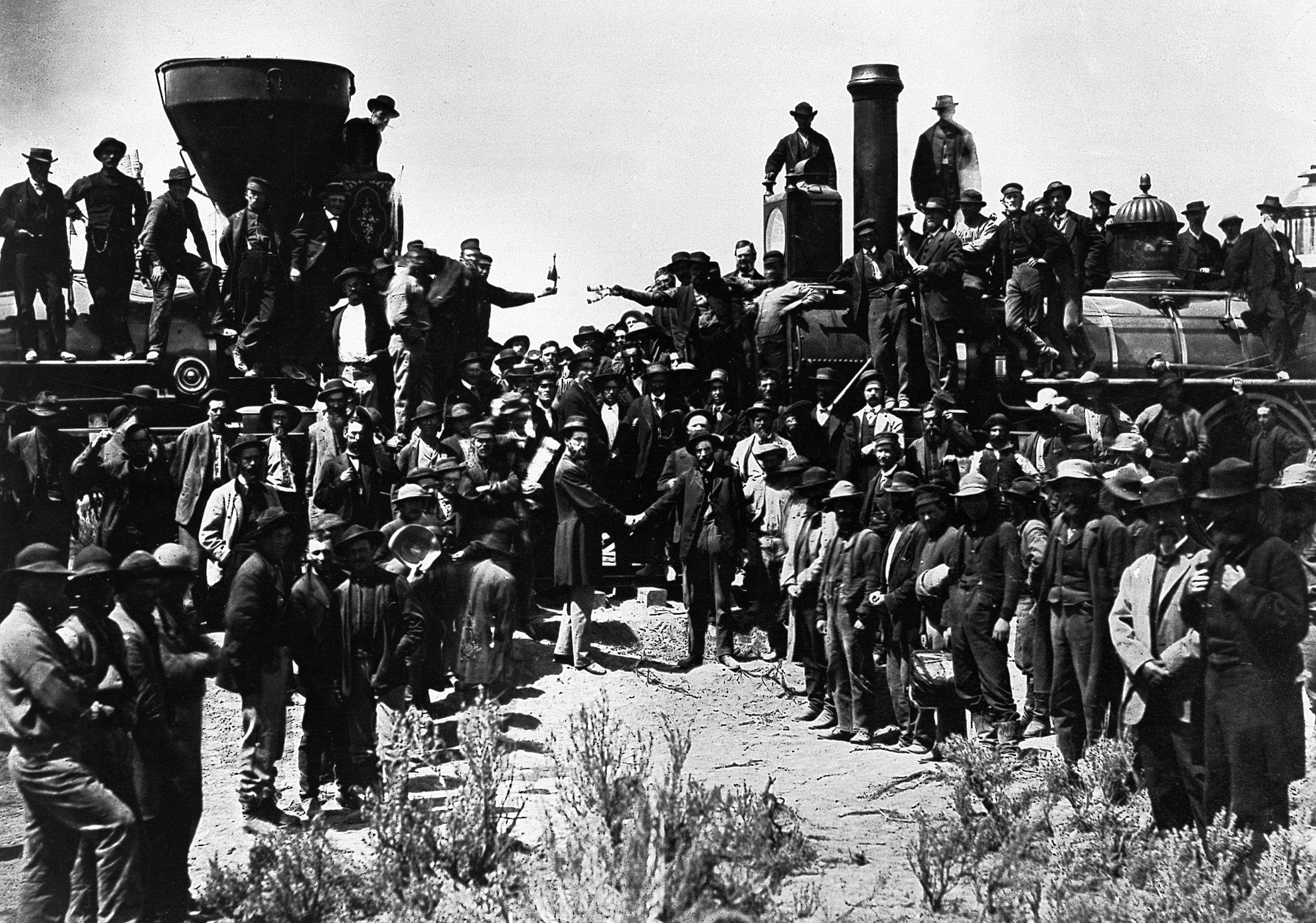

The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 authorized a transcontinental rail line. The Union Pacific Railroad built this line westward from Omaha, Nebraska, and the Central Pacific Railroad built it eastward from Sacramento, California. These two lines met at Promontory, Utah, in 1869. On May 10, to mark the achievement, officials of the two railroads drove silver and gold spikes to join the rails. This feat made possible coast-to-coast travel in 8 to 10 days. Later railway lines, including the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe and the Great Northern, added further travel options. The iron horse had conquered the West.

In addition to bringing settlers west, railroads stimulated many economic activities. Towns vied to attract rail routes. Railroads enabled people to ship wheat, corn, cattle, sheep, mining ore, and other products more quickly and cheaply. Such companies as Montgomery Ward of Chicago could ship goods to westerners who had ordered them through the companies’ mail order catalogs. Railroads even boosted tourism. In the 1880’s, for example, wealthy easterners began boarding trains to spend time on dude ranches, which provided them a brief taste of western ranch life.

New forms of communication

also transformed the West. During the early days of the frontier, a letter took months to travel from the Midwest to California. But several developments soon made communication much faster. In April 1860, a mail service called the pony express began carrying mail between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento. The service’s horseback riders usually made their long journey in about 10 days (see Pony express).

The telegraph soon ended the need for the pony express. This instrument, the first used to send messages by means of wires and electric current, could transmit messages in minutes. Transcontinental telegraph service was established in 1861. By about 1900, however, the recently invented telephone had begun to cause a decline in telegraph use.

Improvements in farming

further stimulated western settlement. Harsh conditions in the West forced immigrant farmers to find new ways of farming. Unpredictable rainfall and thick, grass-covered sod presented challenges. Pioneers began dryland farming on the Great Plains, meaning they grew crops without irrigation in relatively dry regions (see Dryland farming). By plowing soil deep and frequently, farmers could raise crops in lands previously thought unproductive. Inventors helped find ways to make it easier to plow, plant, and harvest crops in tough prairie sod and heavy, sticky soil. In 1837, John Deere, an Illinois blacksmith, developed a more effective plow by incorporating steel into the moldboard, the curved part of a plow that turns the soil to one side. Cyrus McCormick’s new mechanical reaper harvested grain more efficiently than did hand methods. In 1858, Lewis Miller patented a mowing machine that permitted farmers to gather grain into bundles, again improving efficiency. Horses, mules, and oxen provided the power for plowing, hauling, and other farm chores. Tractors and trucks would not appear until the 1900’s.

Farmers needed seeds, equipment, household goods, animal feed, and credit. Thus small towns began to dot the western landscape as retail businesses and banks arose to serve the growing population. Social centers, including churches, schools, and saloons, grew as well. By the late 1800’s, the West had become a patchwork of farms, ranches, and towns amid vast open spaces. So much of the Far West had filled up by 1890 that the Census Bureau declared in a report that a definite frontier line no longer existed.

The people of the western frontier

Early occupants.

In the 1840’s, the American West was sparsely occupied. The largest groups of residents included Indigenous Americans, who lived throughout the region, and Spanish-speaking settlers, who were dominant in the Southwest.

Indigenous Americans, whose cultures were many thousands of years old, had developed an amazing range of adaptations to the American West. Agriculture, fishing, and hunting and gathering provided a varied diet. After the Spaniards introduced horses to the Great Plains in the 1600’s, many Indigenous people became superb mounted hunters and warriors. Until the late 1800’s, huge herds of bison offered an ample supply of food and materials for building and clothing.

The shifting frontier had devastating effects on Indigenous cultures. White settlers pushed Indigenous Americans off their lands. Resistance by Indigenous peoples often led to wars with the U.S. military, which the Indigenous groups usually lost. As western lands came under white control, settlers turned grasslands into farms and ranches and hunters nearly wiped out the region’s vast buffalo herds.

Spanish-speaking settlers had inhabited what is now the American Southwest since the late 1500’s. Farming and ranching occupied most workers, though mining occurred in certain areas. Spanish missions and ranches attracted some Indigenous people, who converted to Roman Catholicism and took up the Spanish language and culture. By the time American settlers arrived in the 1800’s, Spanish culture had become well established throughout much of the Southwest.

Newcomers.

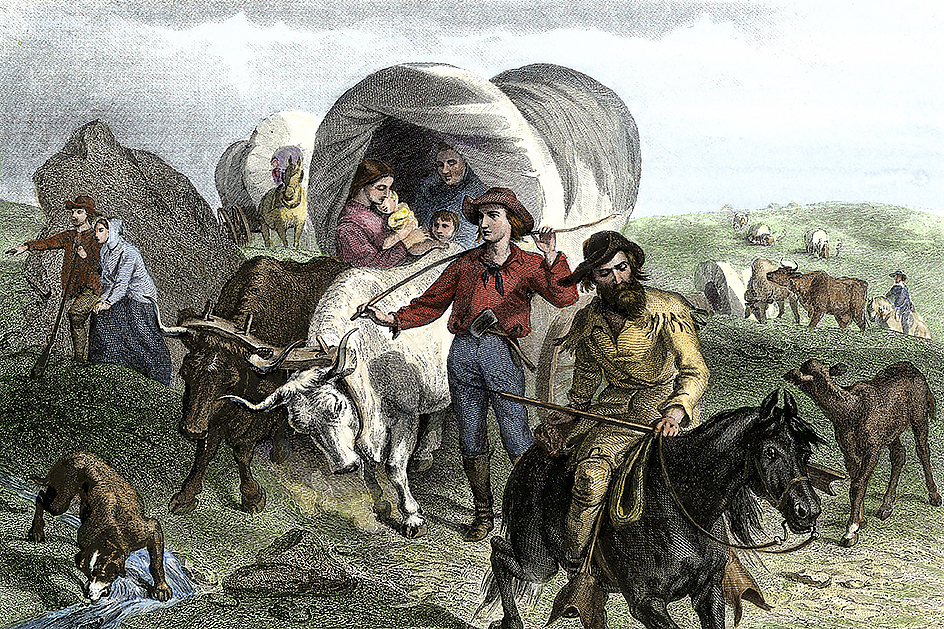

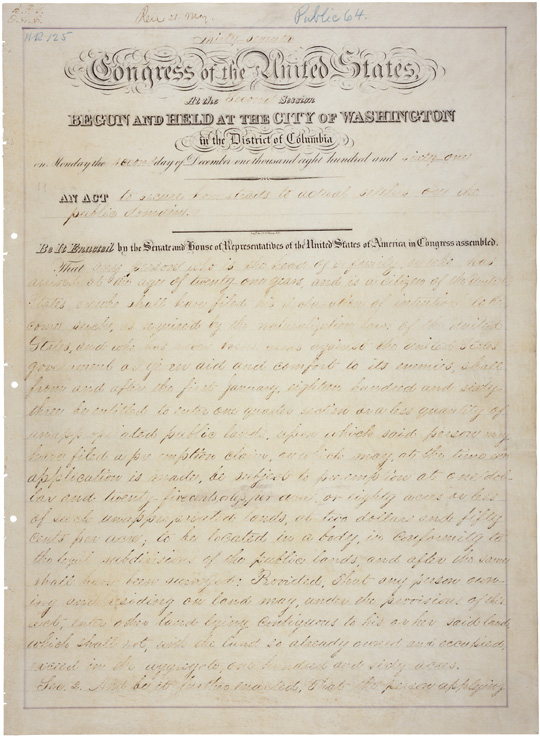

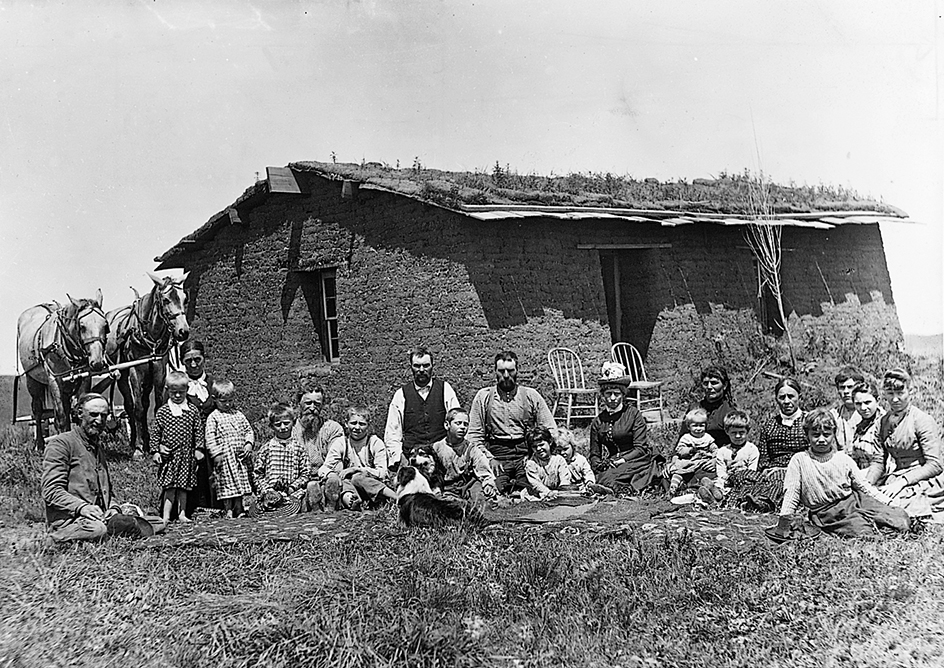

Immigrants to the West arrived from a wide range of backgrounds and locations. A large number of these newcomers came from the eastern United States. Others came from outside the country. Mining and ranching attracted mostly young adult males. Farming drew entire families. The U.S. Congress assisted them with laws to encourage settlement. For example, the Pre-emption Act of 1841 and the Homestead Act of 1862 made purchasing western lands easier.

The newcomers came for various motives. For example, Mormons migrated to escape religious persecution, and large numbers of African Americans traveled west to escape racial discrimination. Many others, such as Chinese workers, sought economic opportunity.

Brigham Young led about 3,000 Mormons to Utah’s Great Salt Lake Valley in 1847. This religious group is formally known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Mormons had decided to leave their home in Illinois in search of religious freedom after the murder of Mormon founder Joseph Smith in 1844.

A later Mormon immigrant from England, Jean Rio Baker, kept a diary of her journey in 1851. She despaired over the road that “was completely covered with stones as large as bushel boxes, stumps of trees, with here and there mud holes, in which our poor oxen sunk to the knees.”

The hardy Mormon pioneers settled in the valleys of north-central Utah. They irrigated the valleys and made farming productive. The Mormons also established Salt Lake City. Utah eventually became a U.S. state in 1896.

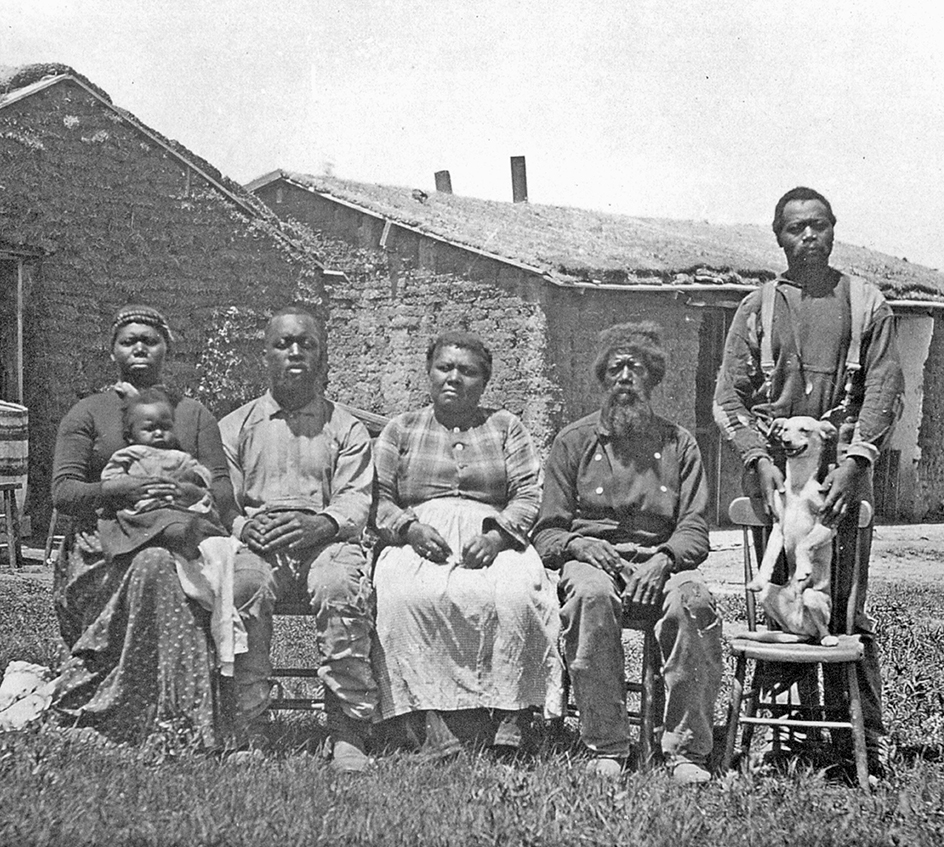

Thousands of Black Southerners settled in the West, mainly in Kansas, after the American Civil War (1861-1865). Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, a formerly enslaved man from Tennessee, led the migration movement. The Black Americans who went west were called “Exodusters” because of their exodus (mass departure) to the dusty frontier. Yet most of the Exodusters faced the same discrimination in their new homes as they had faced in the South. An 1880 article in Scribner’s Monthly magazine described their labors, saying “about one-third are supplied with teams and farming tools, and may be expected to become self-sustaining in another year.” But the remaining two-thirds had to work as day laborers or house servants for white farmers and ranchers.

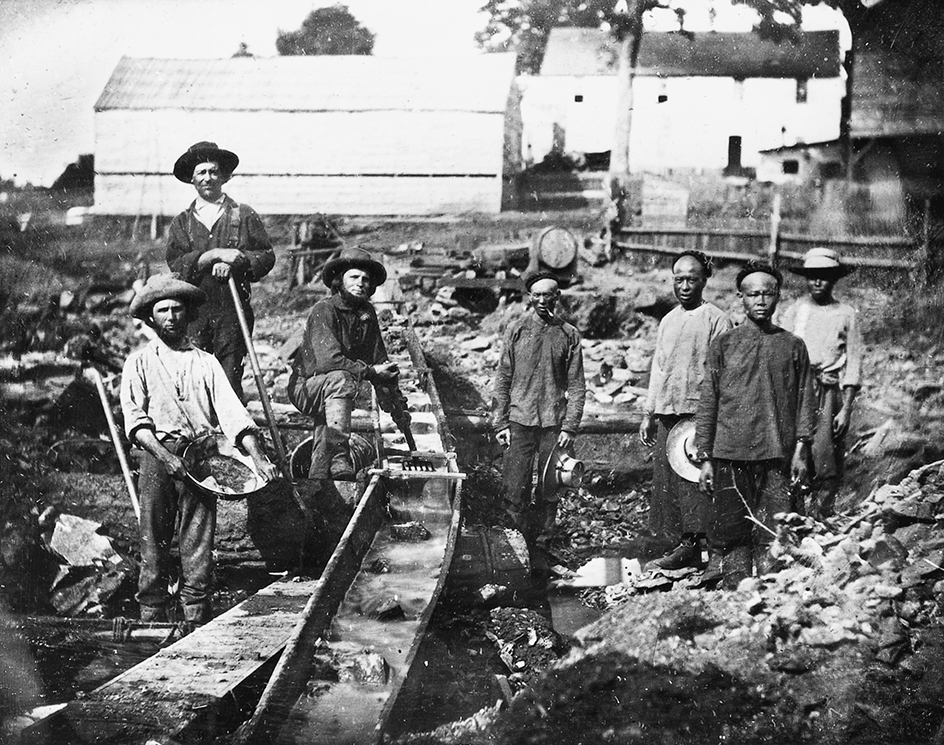

Some Chinese immigrants came to the West as contract laborers (workers imported under an agreement to work for a particular employer). The first group of Chinese arrived in San Francisco in 1848. Four years later, more than 20,000 Chinese arrived. In the 1860’s, the Central Pacific Railroad recruited thousands more Chinese to build the rail line. The Union Pacific hired thousands of Irish and other Europeans for the same purpose. By 1880, about 105,000 Chinese lived in the United States, mostly in California. Their presence sparked mob violence and calls for immigration restrictions, mostly by laborers who felt that the Chinese undercut wages and working conditions. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, prohibiting the immigration of Chinese workers.

Mining

The quest for gold and other precious minerals drew tens of thousands of immigrants to the West. In 1848, a millwright named James Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill, California. His discovery touched off the first and greatest western gold rush. Within two years, 100,000 people had flocked to California to make their fortune. Would-be miners arrived from around the world. Most ended up sick, broke, or both. Merchants sold goods and services to miners at highly inflated prices.

Men made up nearly all of the gold seekers who rushed west. A few women mined, but most worked as entertainers in saloons or dance halls, as seamstresses, or as laundresses who washed miners’ clothes. Other women operated boardinghouses or worked as prostitutes. Chinese immigrants also set up laundries in some mining camps, but they often faced discrimination and violence.

Subsequent finds drew more fortune hunters to other western sites. Southwestern Oregon yielded gold nuggets in the early 1850’s, luring miners north from California. Prospectors flocked to the area near Pikes Peak in Colorado and the Comstock Lode in western Nevada in 1859. In 1873, four miners hit the “Big Bonanza,” a vein of gold and silver near Virginia City, Nevada. In the mid-1870’s, gold miners poured into the Black Hills of South Dakota. The Black Hills town of Deadwood became famous for its lawlessness, corruption, and prostitution. In 1878, prospectors discovered rich deposits of silver near Leadville in central Colorado.

Other minerals also spurred mining booms. Copper deposits in Butte, Montana; Bingham Canyon, Utah; and Jerome, Arizona, provided employment for many miners. Toward the end of the 1800’s, oil, known as “black gold,” became the great strike-it-rich commodity of the West. Bartlesville, Oklahoma, became an oil boom town in 1897, followed by Beaumont, Texas, in 1901.

A typical mining camp.

A prospector pounded wooden stakes into the ground to mark his claim. If he found no gold, he “pulled up stakes” and moved on to stake a new claim. He might also unscrupulously “salt” the claim—that is, he would plant a few gold nuggets there to trick a buyer into purchasing the worthless site.

Mining camps began as primitive, homemade affairs. One gold seeker explained, “I pitched my tent, built a stone chimney at one end, made a mattress of fir [branches], and thought myself well fixed for the winter.” Miners built shacks out of logs and scraps of wood and canvas. Lice, rodents, and other pests infested the primitive dwellings.

Most miners began working their claim by panning. They dipped up sand and gravel from the riverbed into a metal pan and swirled it around. Heavier gold settled to the bottom. Fine “flour” gold might require using mercury to form a mixture from which the gold could be separated. Miners could use a box on rockers to agitate gravel and water, thus removing the gold from the mix. More elaborate claims might include a sluice, a series of long, slanted wooden boxes into which was dumped gravel and water. This action separated the tailings (lighter earth) from the heavier gold. Away from river sites, miners searched for quartz, a glassy rock that often contained gold. They hacked away at the earth with pickaxes and shovels. Larger mining companies dug deep into hillsides, creating underground mines.

Like other westerners, miners lived a difficult life. Digging or panning for gold or silver meant long hours under the hot sun, often working in cold mountain waters. In 1850, a miner named William Swain described the weather at his dig along California’s Yuba River as “five months’ rain, four months’ high water, and three months’ dry and good weather but very hot—almost too hot to work.” Leather boots, vests, and aprons deteriorated quickly. Rocks tore holes into pants and shirts. Most clothes needed constant patching.

Life in the mining towns.

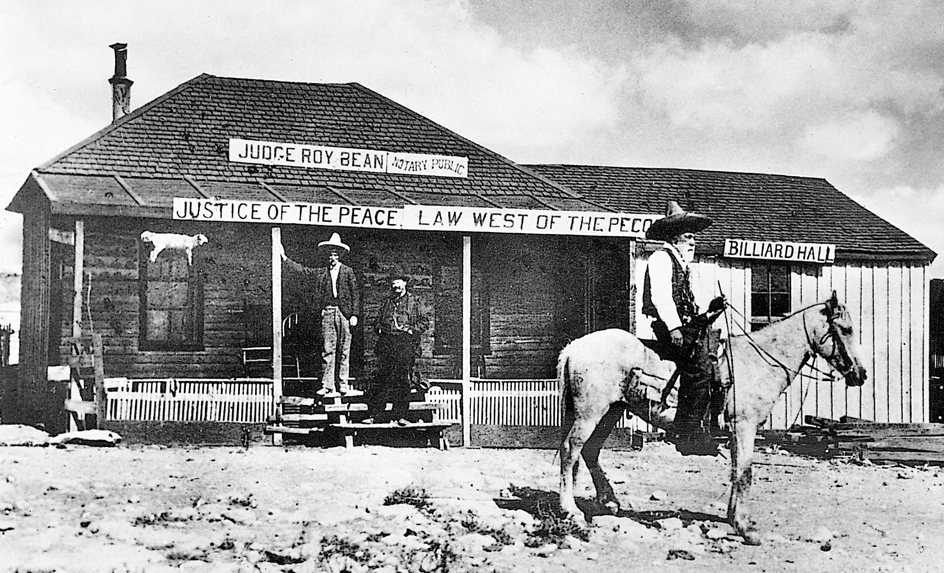

Few women and children lived in mining camps. Only if a mining camp grew into a more stable town did the population diversify. If the camp prospered, it might grow into a boom town with retail stores, a jail, saloons, dance halls, and assay offices to evaluate and weigh gold.

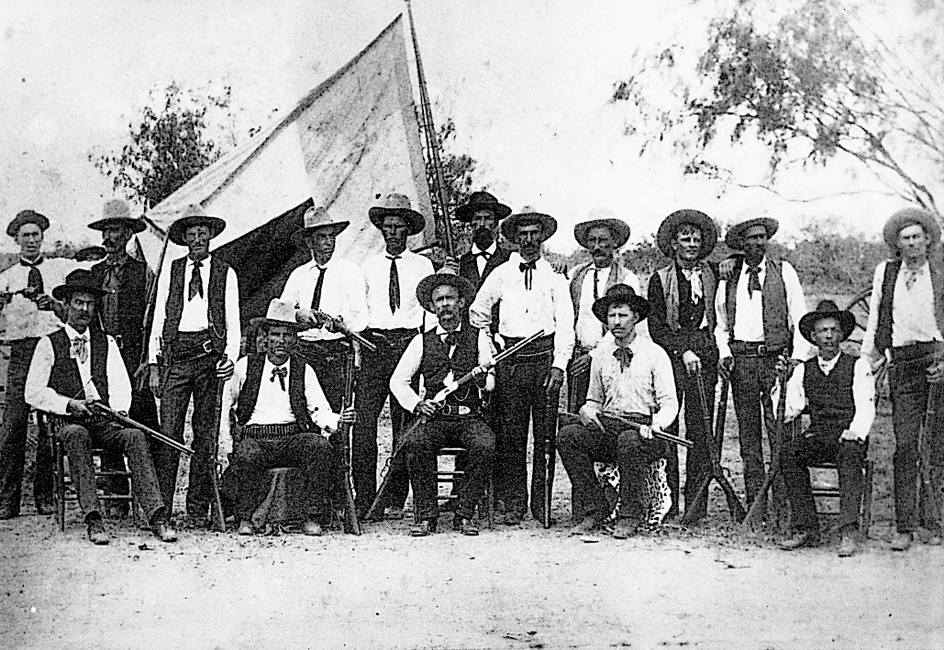

Mining booms swelled local populations quickly, outstripping the supply of almost everything, including food and work animals. Men sometimes killed each other for such necessities. Some mining communities formed governing councils and created codes of conduct. These councils handled robberies, assaults, and other crimes. In some cases, mob violence and lynchings took the place of legal proceedings. Organized police forces and judges came only gradually to the West.

Conflicts broke out between mining companies and miners as the latter tried to organize into labor unions. Such labor groups as the Western Federation of Miners protested, demanding legal protections and better conditions under which to work. The labor organizer Mary Harris Jones, better known as “Mother Jones,” spent her long life working to improve conditions for miners.

Ranching

Centers of ranching.

Spanish and later Mexican ranchers had grazed cattle in the Southwest since about 1700. Ranches and missions with Indigenous labor raised livestock. Local markets purchased meat, and ranchers in California exported cattle hides, tallow (beef fat), and dried beef. Newcomers to the West continued much of this ranching tradition in the middle and late 1800’s.

The Civil War generated a great boom for western ranchers. During the war, most able-bodied Texas men left the state to fight for the Confederacy. Yet their cattle herds increased by several million animals, largely untended. Returning after the war to a surplus of longhorn cattle, Texans faced ruin unless they found new markets. Cattle, worth only a few dollars in Texas, could bring up to $50 a head in eastern markets. So ambitious cattlemen drove herds north to sell them at “cow towns” in Kansas, where buyers had built stockyard holding pens. The animals then traveled east in rail cars to slaughterhouses in Chicago, Kansas City, and elsewhere.

Cattle raising spread gradually northward from Texas and California. Many ranchers got their start by rounding up wild horses and mavericks (unbranded cattle). Monroe Brackins, born into slavery in 1853, spoke of such roundups in south Texas. He said, “I used to rather ketch up a wild horse and break ‘im than to eat breakfast.”

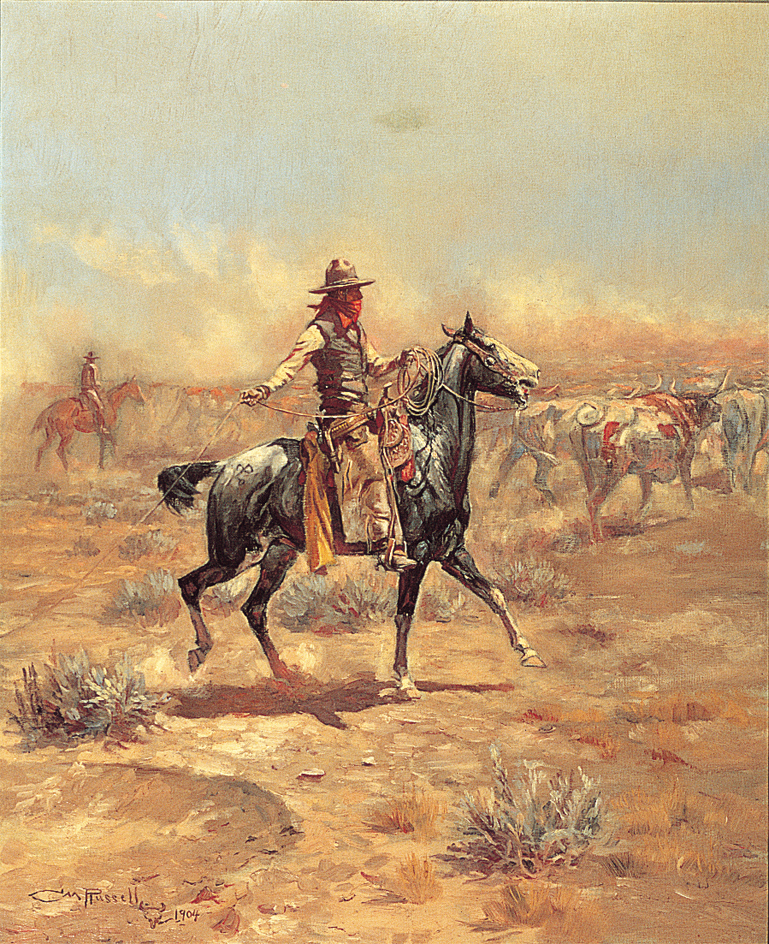

Most cowboys worked on trail drives or in the busier spring and fall roundup and branding seasons. They moved from ranch to ranch, taking work when they found it. Many were Mexican cowboys, called vaqueros << vah KAIR ohz >> , or African Americans.

Life on the ranches.

Ranch houses in the West ranged from humble, dirt-floored lean-tos to lavish mansions. On small ranches on the plains, an entire family might live in a tiny sod hut. If a ranch had forestlands, the rancher likely built a log cabin. A single fireplace provided winter warmth, and a wood-burning stove occupied much of the kitchen. Ranchers would expand and improve the dwellings if they made enough profits.

Larger ranches would have outbuildings, including a barn, outhouse, cookhouse, and a bunkhouse for cowboys. The bunkhouse often had old newspapers as wallpaper, which helped seal out the wind and provided reading material. Simple wooden frames tied by cord made up a ranch hand’s bed. The cowboy slept in the same bedroll that he used on the range.

Entertainment consisted mainly of gambling (usually card games), reading, swapping tall tales, and reciting poems. The poetry of many old-time cowboys got passed along and written down. Today, readers still enjoy the work of such cowboy poets as Charles Badger Clark, Jr., Curley Fletcher, and Bruce Kiskaddon. Cowboys would also stage ranch rodeos, challenging hands from nearby ranches in horse racing and roping. See Cowboy; Ranching.

The cattle drive.

The heyday of the great trail drives came just after the Civil War, when cowhands drove millions of longhorns from Texas to Kansas. The Chisholm Trail, which ran about 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) between southern Texas and Abilene, Kansas, became the main cattle route. Over the years, other cattle trails developed throughout the West. A Texas cowhand named W. L. Rhodes said about cattle drives of the 1880’s, “The first 50 miles of any trail drive is always the hardest because the cattle want to break back to the country they’re used to. We sure had to haze a many a one back before we got the herd used to moving.”

Cowboys faced many dangers on the trail, including lightning, rain, hailstorms, range fires, tornadoes, and rustlers. An 1885 memoir by a cowboy named Charlie Siringo described a trail drive. He wrote, “Everything went on lovely with the exception of swimming swollen streams, fighting now and then among ourselves and a stampede every stormy night, until we arrived on the Canadian river in the Indian territory; there we had a little Indian scare.”

Cattle stampedes could also cause great destruction. A cowboy named Edward “Teddy Blue” Abbott described the result of one stampede, writing that, “horse and man was mashed into the ground as flat as a pancake.” Abbott said, “The only thing you could recognize was the handle of his six-shooter.”

Bad weather, greed, and technology combined to end the great cattle drives. Especially harsh winters in the mid-1880’s killed tens of thousands of cattle trying to forage on the open range. Too many ranchers had overstocked the ranges, leading to lower prices and leaving animals unable to feed themselves on lands that did not produce enough grass in dry weather. Further expansion of western railroads made it cheaper and quicker to haul cattle by train rather than drive them.

Law and order.

Motion pictures and novels often exaggerate the level of the violence in the West, as well as the average cowboy’s skill with a gun. Ambush, rather than one-on-one gun duels, characterized most western killings.

Ranching frontier regions had few law enforcement officers, judges, and jails. At Fort Smith, on the present-day border of Arkansas and Oklahoma, Isaac C. Parker built a reputation as “the hanging judge.” During his 21 years in court that began in 1875, about 160 people received a sentence of death. About half that number were executed by hanging.

Lacking regular law enforcement, other areas often resorted to justice by self-appointed groups of citizens called vigilantes (see Vigilante). People accused of rustling cattle or horses often ended up hanged by such vigilantes. Large cattle ranchers might band together into livestock grower’s associations to protect their interests. They often suspected smaller ranchers and farmers of stealing their livestock. In some cases, they hired gun fighters to track down and kill suspected rustlers. Tom Horn became a celebrated hired gun.

Other types of economic conflict arose. Resentful of encroaching farmers and their fences, some ranchers destroyed barbed wire barriers that cut off access to rangeland grasses and water. Barbed wire, patented by Joseph F. Glidden in 1873, enabled farmers to protect crops against cattle. Cattle and sheep ranchers also fought over access to grass and water. Ethnic violence arose frequently, especially around mining camps, with white miners attacking Chinese and Latin Americans as unwanted competitors.

Farming

The spread of farming.

Pioneer farmers, or homesteaders, began settling in California, Oregon, and other parts of the West during the early 1800’s. After the Civil War, however, western farming expanded greatly. Homesteaders, mostly white, quickly populated the Great Plains from 1870 to 1890. Wheat farms spread across the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma. Idaho became a major producer of potatoes. Other crops included barley, corn, flax, oats, and sugar beets.

Life on the farms.

Early pioneering families had to be self-sufficient. They made or gathered their own clothing, food, shelter, and fuel.

Clothing.

Many farmers kept sheep for food and wool. Women carded (cleaned and combed) the wool and spun and wove it into cloth. Some houses had a large spinning wheel for wool and a smaller one for flax. Women also had to knit mittens, mufflers, and stockings as well as patch and mend older clothing.

Men and boys wore overalls made from denim or recycled grain sacks and a short jacket. Women wore a calico or gingham dress and a sunbonnet. As towns grew in size and mail-order catalogs appeared, settlers could purchase cotton goods to make into clothing. They might use walnut bark, sumac, indigo, and other natural materials to dye the cloth.

Food.

A farm family had to supply its own food. Farmers generally used corn as the staple, often making corn-meal mush, corn muffins, or griddle cakes. They also baked wheat and other grains into bread. Luxuries, such as white sugar and white flour, could only be bought at stores. Cooks sweetened foods with maple sugar, honey, or sorghum molasses. Some farmers planted a fruit orchard that might include apple, cherry, peach, pear, and plum trees. Meat came from such animals as cattle, pigs, chickens, and sheep. A cow supplied milk and cream that families used to make butter and cheese. Farm families, especially women and children, also tended vegetable gardens. They canned or dried much of the crop for winter use. Hunting, fishing, and gathering wild fruits and berries added to the diet.

Shelter.

For many farm families, a humble shelter dug into a hillside provided their first home. A young woman named Laura Iversen Abrahamson described her family’s dugout in South Dakota in the late 1800’s. “Our house is one that Pap and George Monrad dug out of a sidehill,” she said. “The upper part is made of logs, and the roof is of sod.”

Few trees grew on the open plains. Lacking the shelter of a hillside or sufficient trees for a log cabin, farmers on the plains cut sod squares from the soil to use as building material. The sod grasses, with their long, tough, flexible roots, could be cut and stacked to make walls and even the roof. A sod house, often called a soddy or soddie, needed only a small amount of lumber to frame a door and a window or two. The sod insulated reasonably well, except against rain, keeping farmhouses cool during the hot summer and relatively warm in winter. Heavy rain penetrated the roof and could turn the floor into a muddy mess.

Later, farmers would haul in lumber to build houses of wood. Josephine Waybright, who lived on a farm near Ashland, Nebraska, in the late 1800’s, described the improvements that farmers made over time. “When folks got to building bigger and better houses,” she said, “they would arrange them with parlor and a spare room. The parlor was only used when company come and was kept shut up most of the time with the curtains drawn.”

Fuel.

Lack of wood also meant a lack of fuel for cooking and heating. Families typically had to use dried buffalo chips (bison dung) as fuel. The fuel gave off a hot, fast-burning fire with little odor. James G. Eastman, who grew up on a Nebraska farm in the late 1800’s, gathered fuel as one of his childhood jobs. He said, “My mother would send me out to pick up buffalo chips, sunflower stalks, and big weeds and sticks which we piled up for fuel.” A family might spend several weeks in the fall piling up chips to get them through the winter. With the demise of the great buffalo herds in the 1870’s, farm families turned to cow pies (dried cattle dung), cats (twists of dried prairie grass), and dried cornstalks and cobs for fuel.

Recreation.

Isolation on the plains meant that farm families had to make their own fun. Reading and music offered good sources of home entertainment. Guitars, fiddles, harmonicas, and other musical instruments provided amusement. Musicians enjoyed a warm welcome at occasional dances, which families might travel for hours to attend. A quilting bee produced needed bedding and offered women a break from the isolation of plains life.

Holidays provided a chance to socialize and celebrate. Laura Abrahamson described fun at a Fourth of July celebration in South Dakota in 1895. She said, “We had swings and hammocks and played games and had lemonade and cake and had so much fun at the picnic that I guess I’ll feel all right even if I don’t go to anything now for a long time.”

Religion.

Religious services also brought people together. Pioneers often first met in someone’s soddy until an area could support a church building.

Education.

One-room schoolhouses began appearing on the plains. Many early schools were made of sod. Later, more substantial wood or brick school buildings appeared. Students sat in handmade desks and wrote on slates with slate pencils. A single teacher instructed all eight grades. Students had to bring their lunches, usually carried in pails, and sometimes had to bring water as well. They walked or rode horses to class. Vera Pearson, a Kansas homesteader, recalled that teachers had “no charts, no maps, no pictures, no books but a Speller.”

Hardships and challenges.

Great Plains weather could bring extreme heat, cold, rain, wind, or dust. Hattie Erickson, who survived a blizzard in 1888 at her farm in South Dakota, reported, “The storm kept on all night. My kitchen door flew open several times so I had to nail it shut. I think it was the coldest night I ever went through.” The storm killed more than 100 people.

James Eastman recalled prairie fires that “would start way down in Kansas and come clear up to Nebraska. The fires would go faster than any horse could run. Small game, such as rabbits … would be burned alive.” He also told of cold summers that ruined crops. “I have seen frost in Nebraska in July. Seen the leaves freeze off and all of our corn would be ruined.”

Settlers and Indigenous Americans

Westward expansion devastated most Indigenous American cultures. Indigenous groups—peoples once commonly known as Indians—constantly faced the pressure of white settlers and their desire for territory. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson ordered more than 40,000 Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole out of their homelands in the East. The order forced them to move to Indian Territory, a region in present-day Oklahoma. Several thousand people died along the way. The Cherokee came to call their journey the “Trail of Tears,” and this term is sometimes used to refer to the removal of the other groups as well. Other displacements followed as more white settlers moved west.

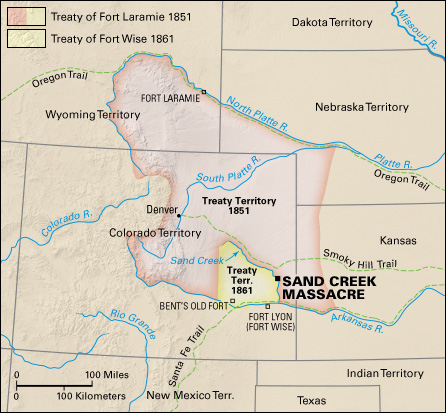

Most white settlers believed Indigenous Americans posed a barrier to U.S. expansion. This mentality sometimes led to the massacre of innocent people. In 1864, Colonel John Chivington commanded Colorado volunteers against a village of Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. The undisciplined troops killed more than 150 men, women, and children.

In 1866, some 2,000 Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Lakota warriors ambushed Captain William J. Fetterman and about 80 of his troops near Fort Phil Kearny in Wyoming. The Indigenous American forces, including the Lakota leader Crazy Horse, wiped out the entire command. In 1868, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer led the Seventh Calvary against a large Cheyenne camp in Indian Territory. The soldiers killed or wounded more than 100 Cheyenne.

Discovery of gold in the Black Hills in the mid-1870’s led to the most famous battle between U.S. troops and Indigenous American forces in American history. Gold seekers flooded the region, ignoring rights to the land held by the Lakota, who were also known as the Teton Sioux. In 1876, Custer attacked a large camp of Indigenous American warriors on the banks of the Little Bighorn River in southeastern Montana. Within a half hour, Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors wiped out Custer’s command. The Lakota Chief Red Horse left an eyewitness account. “These soldiers became foolish,” he said, “many throwing away their guns and raising their hands, saying, ‘Sioux, pity us; take us prisoners.’ The warriors did not take a single soldier prisoner, but killed all of them.” More than 200 soldiers died.

The relentless tide of white immigrants and the near-destruction of the buffalo doomed the Plains peoples to defeat. The last gasp of resistance came with a movement among Indigenous Americans led by the Paiute religious leader Wovoka in 1890. White people called it the Ghost Dance religion because it promised that dead ancestors would return to life. The Lakota medicine man Sitting Bull joined the movement, only to be shot dead when his followers resisted his arrest. A massacre at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, in 1890 ended the resistance by Indigenous Americans.

The West in American culture

The frontier has had a profound influence on American life. Paintings, stories, and films about the West remain an important part of American culture.

Art.

Many artists of the 1800’s and early 1900’s used Western subjects in their work. Alfred Jacob Miller painted pictures of many of the West’s natural wonders, including Independence Rock in Wyoming and the Grand Tetons of the Rocky Mountains. Painter Albert Bierstadt’s work also celebrated the western landscape.

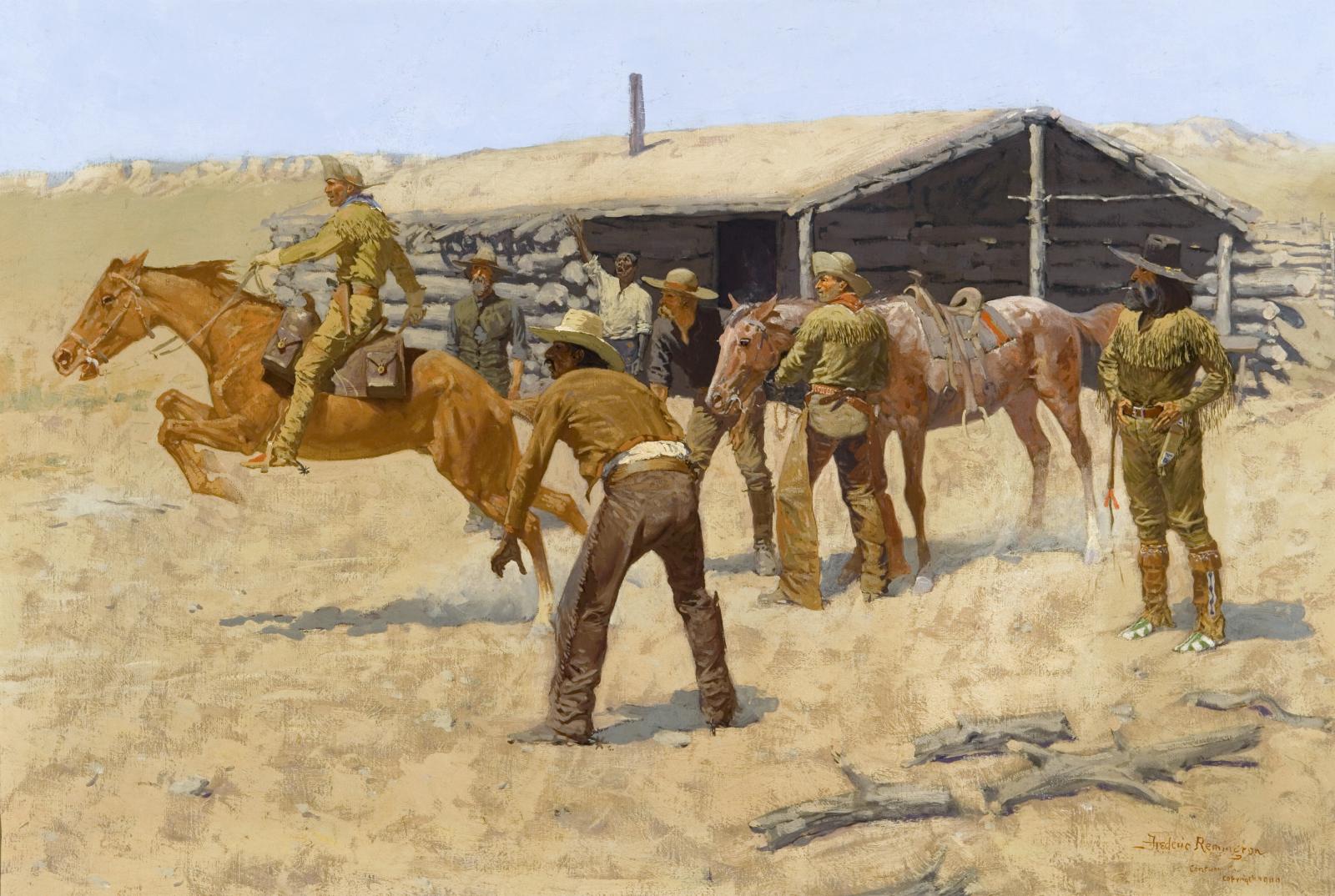

“Cowboys and Indians” also became favorite subjects for artists. George Catlin and Karl Bodmer made memorable paintings of the Indigenous peoples of western North America. Charles M. Russell created paintings and sculptures of the last stages of open-range cowboy and traditional Indigenous life on the northern plains. Frederic Remington sketched, painted, and later sculpted the West’s inhabitants. Like Russell, Remington expressed what he saw as the freedom and heroism of western life. James Walker created important images of California’s vaqueros at work in their colorful costumes.

The mining and farming frontiers played an additional, though smaller, role in American art. Charles Nahl ranked as the best-known artist to celebrate the mining frontier. His works include the painting Sunday Morning in the Mines (1872).

Literature.

Novelists found the West and its colorful people irresistible subjects. Fanciful tales came from so-called “pulp novelists” in the late 1800’s. Seldom having seen the West, these writers churned out cheap literature filled with strong heroes, women in need of saving, and savage outlaws. “Dime novels,” such as those by Edward L. Wheeler, sometimes romanticized and exaggerated the actions of such real western figures as Martha “Calamity Jane” Canary (also spelled Cannary).

Two easterners, Theodore Roosevelt and Owen Wister, promoted their own romantic versions of the West. Roosevelt, after a failed effort at ranching in the Dakotas, wrote a four-volume history called The Winning of the West (1889-1896). He later became president of the United States. Wister’s novel The Virginian (1902) raised Western fiction to a position of critical respect.

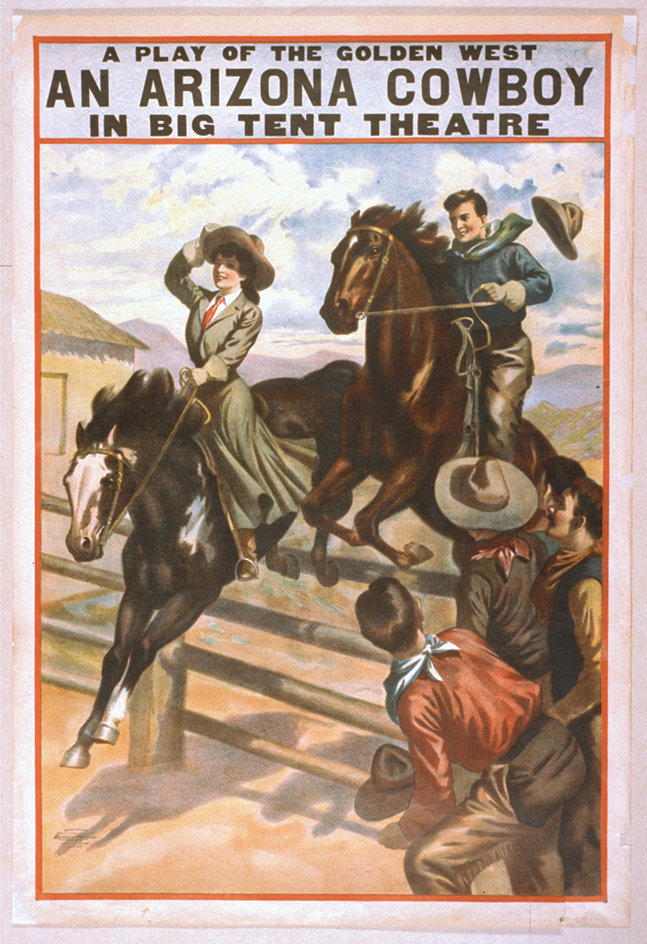

Entertainment.

Ned Buntline, the pen name for Edward Zane Carroll Judson, helped the frontiersman Buffalo Bill become a hero to easterners. Buffalo Bill, whose real name was William Frederick Cody, starred in Buntline’s play The Scouts of the Prairie (1872). Buffalo Bill later started a traveling “Wild West” show that became an international hit. Running from 1883 until 1913, the show thrilled audiences with galloping cowboys and Indigenous riders, great marksmanship by Annie Oakley, and imaginative re-creations of historical Western events.

The allure of cowboy action drew audiences to rodeo competitions (see Rodeo). Originally, cowboys from different ranches tested their riding and roping skills against one another. But such competitions became more formal and began offering prize money. By the early 1900’s, Cheyenne Frontier Days in Wyoming, the Pendleton Round-Up in Oregon, and dozens of other rodeos drew competitors from across the country.

New media of the 1900’s—film, radio, and television—brought Western heroes to larger audiences. The cowboy became the best-known and most popular Western figure. From the early days of silent Western films, cowboy stars dominated the box office. Bronco Billy Anderson, Tom Mix, William S. Hart, and other silent film cowboys entertained moviegoers in the early 1900’s. Beginning in the 1930’s, sound films brought the excitement of galloping hooves and blazing guns to the screen. A new generation of heroes arose, including John Wayne and singing cowboys Gene Autry and Roy Rogers. Many Western films took their plots from “shoot ’em up” novels by Zane Grey, Max Brand, and others.

In the early 1950’s, some Western film stars, including Autry and Rogers, made successful transitions to television. Westerns dominated much of prime-time television through the mid-1960’s. Today, Americans continue to revere their frontier past as a time of strength, courage, self-reliance, and honesty.