Wheat is one of the world’s most important food crops. Hundreds of millions of people throughout the world depend on foods made from the kernels (seeds or grains) of the wheat plant. The kernels are ground into flour to make breads, cakes, cookies, crackers, macaroni, spaghetti, and other foods.

Wheat is a member of the grass family. It belongs to the group of grasses called cereals or cereal grains. Other important cereals include rice, corn, barley, sorghum, oats, millet, triticale, and rye.

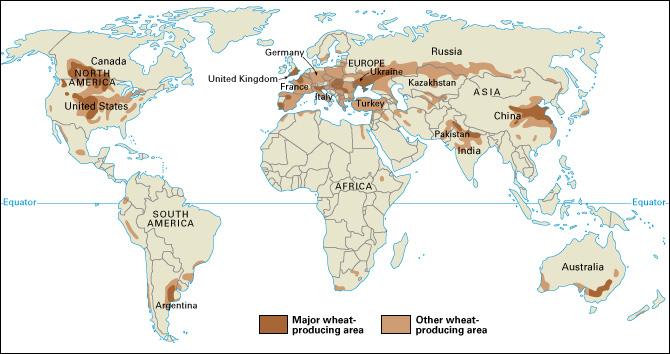

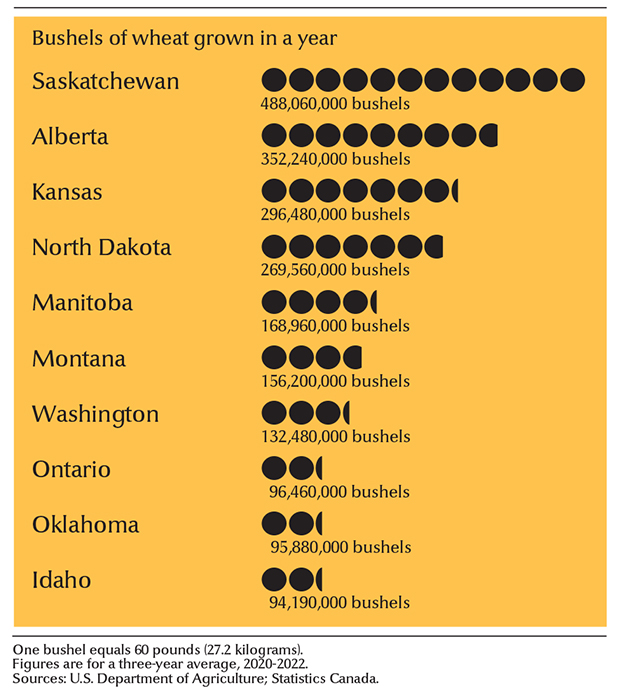

Wheat covers more of Earth’s surface than any other food crop. The world’s farmers grow more than 25 billion bushels of wheat a year. A bushel of wheat weighs 60 pounds (27 kilograms). The leading wheat-producing countries include Canada, China, France, India, Russia, Ukraine, and the United States. About 45 percent of the world’s wheat is grown in Asia.

Long before the beginnings of agriculture, people gathered wild wheat for food. Scholars believe that about 11,000 years ago people in the Middle East took the first steps toward agriculture. Wheat was one of the first plants they grew. In time, farmers raised more grain than they needed to feed themselves. As a result, many people did not have to produce their own food and were freed to develop other useful skills. These changes led to the building of towns and cities, the expansion of trade, and the development of the great civilizations of ancient Egypt, India, and Mesopotamia.

Early farmers probably selected kernels from their best wheat plants to use as seeds for planting the next crop. In this way, certain desired qualities were passed on from one generation of wheat to the next. Such practices resulted in the gradual development of improved kinds of wheat. During the 1900’s and into the 2000’s, scientists developed many new wheat varieties that produce large amounts of grain and can resist cold, disease, insects, and other crop threats. As a result, wheat production rose dramatically.

Uses of wheat

Food for people.

Wheat is the most important food for a large fraction of the world’s people. In many areas of the world, wheat appears in some form at nearly every meal. Wheat is eaten chiefly in bread and other foods prepared from wheat flour. People also eat wheat in macaroni, spaghetti, and other forms of pasta and in breakfast cereal.

Wheat flour

is excellent for baking because it contains a protein substance called gluten that makes dough elastic. This elasticity allows dough containing yeast to rise. Most of the wheat flour milled is used by commercial bakers to bake bread, buns, cakes, cookies, crackers, pies, rolls, and other goods. In addition, wheat flour and baking mixes containing wheat flour are sold for use at home.

To produce wheat flour, millers grind the wheat kernels into a fine powder. Wheat kernels are rich in nutrients (nourishing substances), including protein, starch, vitamin E, and the B vitamins niacin, riboflavin, and thiamine. The kernels also contain such essential minerals as iron and phosphorus.

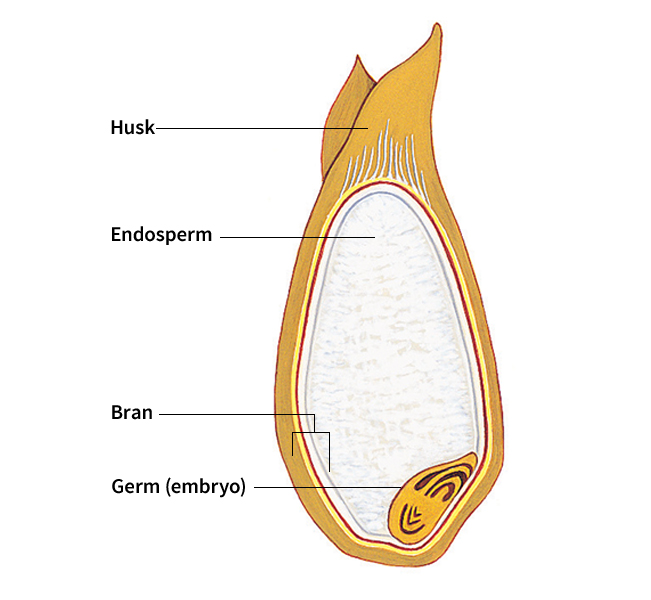

Whole wheat flour is made from the entire kernel. It therefore contains the nutrients found in all parts of the kernel. To produce white flour, however, millers grind only the soft, white inner part of the kernel, which is called the endosperm. The endosperm contains the gluten and nearly all the starch in the kernel. But white flour lacks the vitamins and minerals found in the bran—the kernel’s tough covering—and the germ, which is the embryo (undeveloped stage) of a new wheat plant inside the kernel. In the United States, Canada, and many other countries, millers and bakers add B vitamins and iron to most white flour to increase its food value. Such flour is called enriched flour. See Flour.

Pasta.

Wheat is the chief ingredient in macaroni, spaghetti, and other forms of pasta. Most pasta is made from semolina—the coarsely ground grain of durum wheat. Manufacturers of pasta products add water and other ingredients to the semolina to form a thick paste or dough. They force this paste through machines that form it into macaroni, noodles, spaghetti, and other shapes. See Pasta.

Breakfast foods.

Many breakfast foods are made with wheat. Ready-to-eat breakfast cereals containing wheat include bran flakes, puffed wheat, shredded wheat biscuits, and wheat flakes. Cooked breakfast cereals made with wheat include cracked wheat, farina, malted cereals, rolled wheat, and whole wheat meal.

Livestock feed.

Some wheat germ and bran that remain after white flour is milled are used in feeds for poultry and other livestock. Farm animals also eat wheat when it is economical to feed it to them.

Other uses.

Wheat is also the source of certain substances that are used to improve the nutritional value or flavor of foods. Vitamin-rich wheat germ and wheat germ oil are added to some breakfast cereals, specialty breads, and other foods. Glutamic acid obtained from wheat is used in making monosodium glutamate (MSG). Monosodium glutamate is a salt that has little flavor of its own, but it brings out the flavor of other foods. See Monosodium glutamate.

The stems of wheat plants are dried to make straw, which can be woven into baskets and hats, made into strawboard for boxes, or used as animal bedding or to protect plants as mulch. Industry uses the outer coatings of wheat kernels to polish metal and glass. Adhesives made with wheat starch hold layers of plywood together. Alcohol made from wheat is used as a fuel and in manufacturing synthetic rubber and other products.

The wheat plant

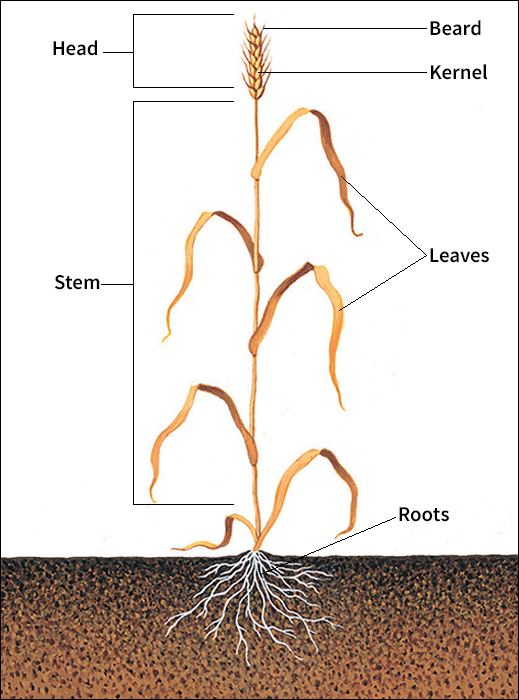

Young wheat plants have a bright green color and look like grass. The mature plants grow 2 to 5 feet (0.6 to 1.5 meters) tall. They turn golden-brown when ripe.

Structure.

The main parts of a mature wheat plant are the roots, stem, leaves, and head. Wheat has two types of roots, primary and secondary. Three to five primary roots grow out of the seed, about 11/2 to 3 inches (3.8 to 7.6 centimeters) below the surface of the soil. These roots usually live for only six to eight weeks. As the stem begins to grow out of the soil, the secondary roots form just below the surface. They are thicker and stronger than the primary roots and anchor the plant securely in the soil. Most of the root system lies in the upper 15 to 20 inches (38 to 50 centimeters) of soil. But if the soil is loose, the root system may extend as deep as 7 feet (210 centimeters).

Most wheat plants have a main stem and several additional stalks, called tillers. Each leaf of a wheat plant has a sheath and a blade. The sheath wraps around the stem or tiller. The blade, which is long, flat, and narrow, extends from the top of the sheath. Each blade is on the opposite side of the stem from the blade that is just below it.

A wheat head, also called a spike, forms at the top of each main stem and tiller. The head is composed of a many-jointed stem. The head carries clusters of flowers, called spikelets, which branch off from each joint. Each primary spikelet contains a wheat kernel wrapped in a husk. Many kinds of wheat have bristly hairs, called awns or beards, which extend from the spikelets. A typical wheat spike bears 40 to 80 kernels.

A wheat kernel is usually 1/8 to 3/8 inch (3 to 9 millimeters) long. It has three main parts—the bran, the endosperm, and the germ. The bran, or seed coat, covers the surface of the kernel. The bran has several layers and makes up about 14 percent of the kernel. Inside the bran are the endosperm and the germ. The endosperm forms the largest part of the kernel—about 83 percent. The germ, also called the embryo, makes up only about 3 percent of the kernel. It is the part of the seed that grows into a new plant after sowing.

Growth and reproduction.

A wheat kernel begins to absorb moisture and swell shortly after planting. The primary roots appear, and the stem starts growing toward the surface of the soil. One to two weeks later, the young plant appears above the ground. In less than a month, leaves appear and the tillers and secondary roots begin to grow.

In spring when conditions are favorable, stems elongate (lengthen) from the leaf sheaths. Heads appear on the tillers soon afterward. A few days after the spike emerges from the sheath, the flowers are pollinated and develop into wheat kernels. Unlike many other flowers, wheat flowers do not attract pollinating insects. Instead, a wheat flower usually pollinates itself. Occasionally, the wind carries pollen from one flower to another.

Wheat becomes fully ripe about 30 to 60 days after flowering, depending on the weather. During the ripening period, the kernels increase in size and gradually harden. The entire plant becomes dry and turns golden-brown. Ripe kernels may be white, red, yellow, or even purple, depending on the variety of wheat.

Kinds of wheat

There are several ways of classifying wheat. Wheats can be broadly grouped into winter wheats and spring wheats. Scientists classify wheat according to its species and variety. In addition, governments in many wheat-producing countries have introduced market classes to simplify wheat sales.

Winter wheats and spring wheats

are grouped by their growing season. The kind of wheat planted depends primarily on the climate. Winter wheats are often grown in milder climates than spring wheats. In general, winter wheats produce higher yields.

Winter wheat is planted in the fall and harvested the following spring or summer. It reaches the stage when tillers form and then stops growing as cold weather arrives. The plants resume growing when warm weather returns in the spring. Winter wheat needs such a period of cold weather, with short days and long nights, to flower. If winter wheat is planted in the spring, it ordinarily will not head (produce a crop).

Spring wheat is grown in areas with extremely cold weather. It is planted in the spring of the year and becomes fully ripe that summer.

Species of wheat.

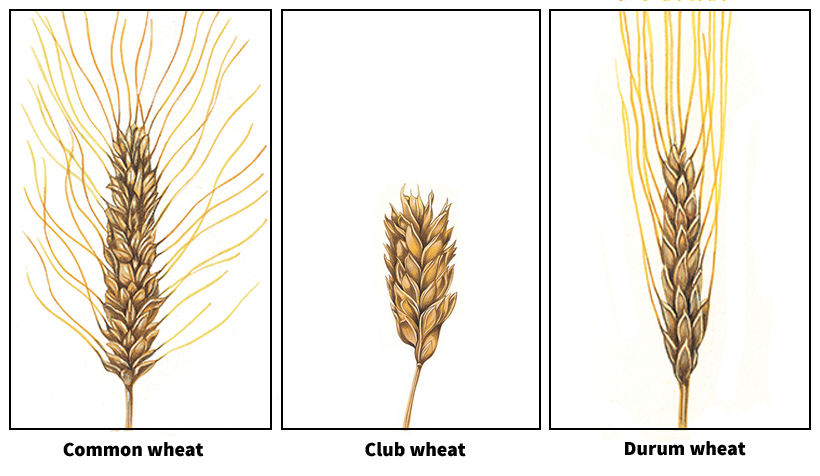

Scientists have identified many species of wheat, based on differences in such traits as appearance and growth patterns. Two species—common wheat and durum wheat—are commercially important. Another commercially important kind of wheat, club wheat, is a subspecies of common wheat.

Common wheat

is also called bread wheat. It is the most widely grown wheat species in the world. The kernels of common wheat may be red, amber (yellowish-brown), white, and in rare cases even purple or blue. They range in texture from hard to soft. Common wheat includes both winter and spring wheats. It is grown on the prairies of the central United States and Canada and in most major wheat-producing areas of the world.

Club wheat

is a subspecies of common wheat. Its kernels are white and are soft in texture. In the United States, club wheat is grown mainly in the Pacific Northwest. Club wheat may be of the winter or spring type.

Durum wheat

has hard kernels that are usually white or amber. Ground durum wheat is particularly high in protein and holds together well when made into a paste. For this reason, durum wheat is used in pasta products. In North America, most durum wheat is of the spring wheat type and is grown in Minnesota, the Dakotas, and southern Canada.

Varieties of wheat.

Each wheat species is divided into many varieties. These varieties differ in such characteristics as grain yield; growing time; grain protein content; and the ability to resist cold, drought, disease, and insect pests.

Tens of thousands of varieties of wheat have been identified around the world. Scientists keep seeking new varieties with the most desirable combination of characteristics. In laboratories at agricultural experiment stations, seed companies, and universities, scientists breed new varieties by a process called crossing. In crossing, pollen from one variety is used to fertilize plants of another variety. The offspring form a new variety with some characteristics of both parent varieties. The offspring with the most desirable characteristics are grown for several generations to ensure that the new variety is pure and has acceptable characteristics.

Commercial classes of wheat.

To assist in the regulation, trade, and marketing of wheat, wheat is often divided into commercial classes. For example, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) divides wheat into seven market classes based on such qualities as the color and texture of the kernels. These classes are: (1) hard red winter wheat, (2) soft red winter wheat, (3) hard red spring wheat, (4) durum wheat, (5) red durum wheat, (6) white wheat, and (7) mixed wheat.

The USDA market classes help the government regulate the quality of wheat sold in the United States. They also help milling companies and exporters select the grain they purchase. Each class has different characteristics and uses. In general, hard wheats have more protein than do soft wheats. Hard red wheats make excellent bread flour. Soft red wheats are used for cakes, cookies, and pastries. Durum wheats are used to make pasta products. White wheats, including club wheat, are soft and best suited for breakfast foods and pastries. Mixed wheats consist of wheats from two or more classes.

How wheat is grown

Wheat grows in a wide range of climates and soils. But a good wheat crop requires suitable weather and proper soil. To achieve the highest yields, wheat farmers must use high-quality seed that is free from disease. Farmers also must plant and harvest the wheat at just the right time. In addition, they must protect the growing crop from damage caused by diseases and pests.

The basic steps for growing wheat are much the same all over the world. However, wheat farms differ in size and levels of mechanization (work done by machinery). In many nonindustrial countries, wheat farmers use animals to pull their plows across small plots. They also may plant and harvest their crops by hand. In industrialized countries, nearly all the wheat is grown on large farms with the aid of tractors and specialized machinery. This section describes how wheat is grown on a large, mechanized farm.

Climate conditions.

Fairly dry and mild climates are the most favorable for growing wheat. Extreme heat or cold, or very wet or very dry weather will destroy both spring and winter wheat. Weather conditions, including temperatures and rainfall, influence when wheat is planted. Planting seeds too early or too late reduces the yield. Late planting of winter wheat also increases the chance of damage from cold.

Farmers plant winter wheat in time for the young plants to become hardy enough to survive the winter cold. In the United States, winter wheat is planted as early as mid-August in Washington state and as late as December in California, where cold weather arrives much later. In northern winter wheat areas, farmers may plant wheat in furrows (narrow grooves) a few inches deep. These furrows fill with blowing snow, which acts like a blanket and protects the plants from extreme cold.

Spring wheat is exposed to fewer weather hazards because it has a far shorter growing period than winter wheat does. Farmers in northern Nebraska and South Dakota may plant spring wheat in early March. Farmers to the north—in Minnesota and North Dakota—may wait until mid-April to plant spring wheat.

Soil conditions.

Wheat grows best in the kinds of soil called clay loam and silt loam (see Loam). The soil should contain much decayed organic (plant and animal) matter to provide food for the wheat plants. If the soil lacks some nutrients, a farmer may add these in the form of fertilizer.

In many parts of the world, farmers grow wheat on the same land every year. After many years, such land may lack the nutrients needed to produce a good crop. In addition, erosion by wind or water can remove nutrients from the soil. Farmers commonly have samples of soil tested to determine if the soil has the necessary nutrients. Such tests also indicate the amount of acid in the soil. If soil becomes too acid, wheat will not grow well and may not even sprout. Farmers can add fertilizer and lime to the soil to restore nutrients and reduce acidity.

Some farmers do not plant wheat on the same land every year. They may plant wheat in rotation with such crops as barley, corn, oats, peas, or soybeans. This practice returns nutrients to the soil and helps control diseases and pests. In regions with little rainfall, farmers may plant a field every other year. Between wheat crops, they leave the field fallow (unplanted) so that it can store moisture.

Preparing the soil.

Wheat farmers prepare fields for the next crop by cultivating. They begin working the soil as soon as possible after harvest. Cultivating breaks up the soil surface and allows moisture to soak into the ground where it is stored for the next crop. It also buries weeds and the remains of the previous crop. This plant matter releases nutrients as it decays. In areas that suffer from erosion, farmers use a cultivator that loosens the soil but leaves plant material on the surface. This material helps reduce erosion.

Just before planting wheat, farmers prepare the seedbed with a device called a spring-tooth harrow. Harrows have sharp metal spikes that break up chunks of soil into small pieces that can pack closely around the wheat seeds.

Planting.

Farmers use a tractor-drawn machine called a drill to plant wheat seed. The drill digs furrows just deep enough to plant the seeds. At the same time, it drops the seeds, one by one, into the furrows and covers the seeds with soil. Some drills also drop a small amount of fertilizer with the seed. Drills can be set to plant the desired number of seeds per acre. Seeding rates range from about 1/2 bushel per acre (1.2 bushels per hectare) in dry regions to about 2 bushels per acre (4.9 bushels per hectare) in moist regions. With a large drill, a farmer can plant more than 600 acres (240 hectares) of wheat a day.

Care during growth.

Growing wheat can suffer damage from diseases, insect pests, and weeds. Wheat farmers employ various practices to help prevent such damage.

Controlling diseases.

The most destructive wheat disease is rust. This disease is caused by a fungus that grows on the wheat plant and produces small, rust-colored spots on the leaves, stems, and heads. The spots later turn yellow or brown. The fungi draw food and water from the wheat plant. This action may prevent the kernels from developing. There are three types of rust: (1) leaf rust, (2) stem rust, and (3) stripe rust. Some varieties of wheat are resistant to certain kinds of rust. Rust can sometimes be controlled by spraying chemicals called fungicides. To reduce the need for such chemicals, breeders continue to develop wheat varieties with genetic (inherited) resistances to rust. See Rust.

Another serious fungus disease that harms wheat kernels is smut. The two main kinds that attack wheat are bunt (also called stinking smut) and loose smut. Wheat kernels infected with bunt fill with a black mass of smut spores. These infected kernels are called smut balls. When smut balls break, they release a rotten, fishy odor. If smut balls break during harvesting, the spores spread and contaminate thousands of other kernels. If infected kernels are sown, the next crop also will be damaged. In wheat plants infected with loose smut, black smut spores replace both the kernels and the husks. Wind carries these spores to other wheat plants, spreading the disease. Farmers can control both kinds of smut by treating the seeds with chemicals before planting. Some varieties of wheat are bred with a genetic resistance to smut infection. See Smut.

Several other diseases attack wheat, in some cases causing widespread damage. They include flag smut, foot rot, fusarium, glume blotch, leaf blotch, scab, and take-all.

Controlling insect pests.

More than 100 different kinds of insects attack wheat. Some, including grasshoppers and locusts, eat the stems and leaves of the wheat plant. Wireworms, cutworms, and some other insects eat the roots and seeds or cut the wheat stem at the surface of the soil. Still other insects, including Hessian flies, suck sap from the stems. Insects that damage wheat also include armyworms, cereal leaf beetles, greenbugs, jointworms, wheat stem sawflies, and wheat stem maggots. Grain weevils and Angoumois grain moths attack stored wheat grain.

Some varieties of wheat have a genetic resistance to Hessian flies and wheat stem sawflies. Farmers can control other insect pests by using insecticide sprays. Planting winter wheat after the Hessian flies that hatch in the fall have died also helps farmers to reduce the crop damage caused by this insect pest.

Controlling weeds.

Weeds rob wheat plants of moisture and nourishment. This loss reduces grain yields. Certain weeds can spoil a wheat crop. For example, wild garlic and wild onions give wheat an odor that makes it unfit for use as flour. Other weeds that cause serious damage to wheat crops include Canada thistle, cheat, field bindweed, Russian thistle, wild morning glory, wild mustard, and wild oats.

Careful preparation of the seedbed helps prevent the growth of weeds. If weeds become a problem among growing wheat plants, farmers may apply chemicals that have been approved for such use by government agencies. Alternatively, a farmer may use a harrow to pull or cut weeds.

Harvesting.

Farmers harvest wheat as soon as possible after it has ripened, before bad weather can damage the crop. Wheat is ready for harvest when moisture makes up no more than 14 percent of the weight of the kernel. To check for ripeness, farmers may take a sample to a grain storage elevator for moisture testing. Farmers also may test wheat by biting a kernel. When ready for harvest, the kernels are hard and brittle and break with a sharp, cracking sound.

Large mechanized farms use huge, self-powered machines called combines to harvest wheat. Combines cut the stalks and thresh the wheat—that is, separate the kernels from the rest of the plant. In North America, large teams of combines follow the wheat harvest north from Texas to Canada. These combine teams move from field to field, sometimes operating day and night to harvest the wheat on time.

Where wheat is grown

The world’s leading wheat-producing countries include Canada, China, France, India, Russia, Ukraine, and the United States. Some countries produce more wheat than their own people consume. Farmers in these countries depend heavily on export sales. Australia, Canada, Russia, and the United States lead all other countries in exports of wheat. Argentina, France, Germany, and Ukraine also export large amounts of wheat. Algeria, Brazil, China, Egypt, Indonesia, Italy, the Philippines, and Turkey are among the world’s leading importers of wheat.

Asia.

In China, farmers grow wheat in many areas of the country, primarily on the North China Plain in the east. Most of China’s farmers plant winter wheat. In some irrigated fields, they plant such crops as corn, cotton, or soybeans between the rows of wheat before the wheat is ready for harvest.

Farmers in Kazakhstan and central Russia grow softer varieties of spring wheat. The growing region is on a level prairie with deep, fertile soils. This area, called the Black Earth Belt, extends about 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) from the Danube River Basin in eastern Europe across northern Kazakhstan and into central Russia.

India, Pakistan, and Turkey are also among the major wheat-producing countries of Asia. Farmers plant winter wheat across much of northern India just after the summer rains stop.

Europe.

Farmers in Moldova, Ukraine, and the European part of Russia grow hard red winter wheat. Other wheat-producing countries of Europe include France, Germany, Italy, Poland, and the United Kingdom.

North America.

In the United States, the many varieties of wheat are planted at different times and in different areas, depending on the climate. In the southern Great Plains—Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Texas—farmers grow hard red winter wheat. In Minnesota and the northern Great Plains—Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota—farmers plant hard red spring wheat. Winters in this region are often too cold for winter wheat. Spring durum wheat is also grown in the northern Great Plains. Smaller amounts of winter durum wheat are planted in Arizona and California.

In the Midwest and the East—in such states as Illinois, Indiana, Missouri, Ohio, and Pennsylvania—farmers commonly plant soft red winter wheat. White wheat is grown in Michigan and New York.

In the Western United States, the chief wheat-producing areas are the Columbia River Valley and the uplands of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. This region has deep, fertile soils that hold water well. Most of the wheat grown is white wheat. White wheat also is grown in California.

In Canada, most wheat is grown in the Prairie Provinces—Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba. About three-fourths of Canada’s crop is spring wheat, though some other wheats, especially durum, are also grown.

South America.

The primary wheat-growing area in South America is the Pampas—a fertile plain in Argentina. Hard red winter wheat is grown on huge, mechanized plantations in the Pampas.

Australia.

Farmers in Australia grow wheat in the southern part of the country. Nearly all of Australia’s crop is white spring wheat.

Marketing wheat

Transporting and storing wheat.

After the harvest, most farmers haul their wheat by truck to a country grain elevator for storage. Each truck empties its load of grain into a pit. A conveyor belt then scoops up the grain, carries it to the top of the elevator, and dumps it into a tall storage bin. Country elevators dry and clean the grain they receive and provide farmers with marketing information. Country elevators assign the grain to one of six grades, based on its weight and quality. The grades have different uses, and wheat is marketed on the basis of its grade. Country elevators receive most of their wheat directly from farmers, but some of the wheat may come from smaller country elevators.

From the country elevator wheat travels by truck or railroad boxcar to a terminal elevator in a large grain market or shipping center. Different lots may be combined at the terminal elevator to produce blends needed by flour mills. If the grain is to be exported, the USDA inspects and grades it. Terminal elevators commonly hold from 1 million to 10 million bushels of wheat, though some can hold much more. See Grain elevator.

From the terminal elevator, some wheat is loaded into huge ships for export. Much of the remainder is carried by truck, rail, or barge to mills for grinding into flour. The rest is shipped to other processors to be used in animal feed or other industrial products. For a description of flour milling, see Flour (How white flour is milled).

Buying and selling wheat.

In the United States, milling companies buy some wheat directly from farmers. Most often, however, country elevators buy the farmers’ wheat. Most wheat stored in grain elevators is sold through a commodity exchange or grain exchange. The CME Group in Chicago and the Kansas City (Missouri) Board of Trade are two large exchanges where grain is traded. An exchange itself does not buy or sell any wheat. It is an organized market where people who want to buy a commodity (good) meet those who want to sell it. These traders include farmers, representatives of grain elevators and flour mills, and exporters. In addition, some traders are speculators—that is, they buy and sell a commodity in the hope of making a profit without actually exchanging the commodity itself.

Buyers may purchase wheat already in storage. The larger exchanges also have a futures market where traders make contracts to buy and sell wheat at a specified price and future date. The futures market helps milling companies and other processors by assuring them a steady supply of grain at prices determined well in advance of delivery. See Commodity exchange.

In Canada, a government agency called the Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) marketed all Canadian wheat for many years. Farmers were required to sell their wheat to the CWB. The CWB bought and sold wheat at prices established by the government, set quotas for purchases from wheat farmers, and regulated exports. Under this system, all farmers received the same price for wheat of similar quality, and they were guaranteed a fair share of the market. In 2012, the government allowed farmers to sell wheat independently. However, the CWB continued on a voluntary basis, and many Canadian farmers continued to sell their wheat to the board. In 2015, the CWB was sold to an international partnership called the Global Grain Group (G3). The board was renamed G3 Canada, Ltd.

Controlling wheat production.

Worldwide wheat production varies greatly from year to year, depending on weather and the amount of land planted. In years of high production, many countries may harvest more wheat than they can use. They can either store the surplus or sell it to countries that need wheat. As countries try to unload their surplus, the price of wheat tends to drop. Sometimes, the price falls far below the farmers’ cost of growing the wheat. If wheat prices remain low, farmers may decide to plant less wheat or switch to another crop. Then, in years of low production, there may be too little wheat to feed the people.

In many countries, the government has farm programs aimed at matching production levels with expected market demand, thus preventing large surpluses or shortages. Some governments support wheat prices by guaranteeing to buy surplus wheat at a “target” price if the market price falls below that price. The government may store the surplus wheat and sell it later when the price rises.

Other government programs aim at increasing or reducing the acreage planted, depending on the country’s needs. The United States, for example, historically has had a wheat surplus year after year. From the 1960’s to the 1980’s, the U.S. government tried to limit wheat surpluses by paying farmers to leave fields unplanted. Such programs also encouraged land conservation.

Since then, the U.S. government has largely moved away from programs that limit planting toward various income support programs. Generally, these programs make direct payments to farmers when the market price of wheat falls below a minimum target price set by legislation. The government pays the farmer the difference between the market price and the target price.

History

Origins.

Scientists believe that wild relatives of wheat first grew in the Middle East. Species from that region—wild einkorn, wild emmer, and some wild grasses—are the ancestors of all cultivated wheat species. At first, people probably simply gathered and chewed the kernels. In time, they learned to toast the grains over a fire and to grind and boil them to make a porridge. Frying such porridge resulted in flat bread, similar to pancakes. People may have discovered how to make yeast bread after some porridge became contaminated by yeast.

Wheat was one of the first plants to be cultivated. Scientists think that farmers first grew wheat about 11,000 years ago in the Middle East. Archaeologists have found the remains of wheat grains dating from about 9,000 B.C. at the Jarmo village site near Damascus, Syria. They also have found bone hoes, flint sickles, and stone grinding tools that may have been used to plant, harvest, and grind grains.

The cultivation of wheat and other crops led to enormous changes in people’s lives. People no longer had to wander continuously in search of food. Farming provided a handier and more reliable supply of food and enabled people to establish permanent settlements. As grain output expanded, many people were freed from food production and could develop other skills. With the improvement of agricultural and processing methods, people in some areas grew enough grain to feed people in other lands. In this way, trade developed. Thriving cities replaced tiny villages. These changes helped make possible the development of the great ancient civilizations.

The spread of wheat farming.

By about 4,000 B.C., wheat farming had spread to much of Asia, Europe, and northern Africa. New species of wheat gradually developed as a result of the accidental breeding of cultivated wheats with wild grasses. Some of the new wheats had qualities that farmers preferred, and so those kinds began to replace older wheats. Emmer and einkorn were cultivated widely until durum wheat appeared about 500 B.C. By about A.D. 500, common wheat and club wheat had developed.

Wheat was brought to the Americas by explorers and settlers from many European countries. In 1493, the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus introduced wheat to the New World on his second trip to the Caribbean. Wheat from Spain reached Mexico in 1519 and Argentina by 1527. Spanish missionaries later carried wheat with them to the American Southwest. In Canada, French settlers began growing wheat in Nova Scotia in 1605.

English colonists planted wheat at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1611 and at Plymouth Colony in New England in 1621. But the New England colonists had less luck with wheat than with the corn the Indians gave them. Colonists from the Netherlands and Sweden had more success growing wheat in New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

Wheat farming moved westward with the pioneers. Wheat grew well on the Midwestern prairies, where the climate was too harsh for many other crops. Large shipments of wheat traveled to markets in the East by canal and railroad. By the 1860’s, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, and Ohio had become leading wheat-producing states.

The introduction of winter wheat gave the U.S. wheat industry a major boost. In the 1870’s, members of a religious group called the Mennonites immigrated from Russia to Kansas. They brought with them a variety of winter wheat called Turkey Red, which was extremely well suited to the low rainfall on the Great Plains. Turkey Red and varieties that were developed from it soon were planted on nearly all the wheat farms in Kansas and nearby states. Many present-day varieties of wheat grown in the United States can be traced to Turkey Red.

The mechanization of wheat farming.

From the beginnings of agriculture until the early 1800’s, there was little change in the tools used for wheat farming. For thousands of years, farmers harvested wheat by hand with a sickle or a scythe. The stalks were then tied into bundles and gathered into piles to await threshing. To thresh the grain, livestock trampled the stalks or farmers beat the stalks with a hinged stick called a flail. After the grain was loosened from the stalks, the wheat was tossed into the air. The chaff blew away, leaving the kernels behind. This process was called winnowing. Much grain spoiled because it took so long to harvest and thresh it.

Machines that were developed in the 1800’s made wheat farming far more efficient. The American inventor Cyrus McCormick patented the first successful reaping machine in 1834. By the 1890’s, most reapers had an attachment that tied the stalks in bundles. Also in 1834, two brothers from Maine, Hiram and John Pitts, built a threshing machine. The thresher could do in a few hours the work that once took several days. A combined harvester-thresher, or combine, was developed in the 1830’s by Hiram Moore and John Haskall of Michigan. However, most farmers continued to use separate reapers and threshers. During the 1920’s, a shortage of farm labor coupled with improvements in combines led more farmers to use them.

Until the late 1800’s, most farm equipment was powered by farm animals or human labor. During the 1880’s, steam engines gradually replaced the animals that pulled most farm machinery in the United States. By the early 1920’s, internal-combustion engines were used to power tractors and other farm machines.

Mechanization has greatly reduced the amount of human labor needed to grow wheat. Before 1830, it took a farmer more than 64 hours to prepare the soil, plant the seed, and cut and thresh 1 acre (0.4 hectare) of wheat. Today, it takes less than 3 hours of labor. Mechanization has also enabled farmers to cultivate much larger areas. Using hand tools, a farm family can grow about 2.5 acres (1 hectare) of wheat. But with modern machinery, the same family can farm about 1,000 acres (405 hectares).

Breeding new varieties of wheat.

Some of the most important advances in the history of wheat resulted from the scientific breeding of wheat begun during the 1900’s. By developing new varieties of wheat, plant breeders greatly increased the yield of wheat per acre or hectare of land. Some varieties have higher yields because they have a genetic resistance to diseases or pests. Others mature early, enabling the grain to escape such dangers as early frosts and late droughts. Breeders also developed plants with strong stalks that can support a heavy load of grain. Many high-yield varieties require large amounts of fertilizers or pesticides. Some modern breeding programs are developing high-yield varieties that require less fertilizer and pesticides.

During the mid-1900’s, agricultural scientists led a worldwide effort to boost grain production in developing countries. This effort was so successful that it has been called the Green Revolution. Its success depended primarily on the use of high-yield grains. In 1970, American agricultural scientist Norman E. Borlaug was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for wheat research that led to the development of these varieties. See Borlaug, Norman E.

The Green Revolution reduced the danger of famine in many developing countries. It helped these countries become less dependent upon imported wheat for their growing population. It also helped focus attention on obstacles to increasing the world’s food supply. For example, water supplies are often limited and soils are of poor quality. Many farmers cannot afford irrigation systems or the large amounts of fertilizers and pesticides the new wheat varieties require. In some developing countries, grain can be damaged or spoiled by insects, rodents, poor transportation, and poor distribution systems. Finally, in many countries, the population is growing faster than the food supply, offsetting the gains achieved by the Green Revolution.