Bird is an animal with feathers. All birds have feathers, and they are the only living animals that have them. When people think of birds, they usually think first of their flying ability. All birds have wings. The fastest birds can reach speeds well over 100 miles (160 kilometers) per hour. No other animals can travel faster than birds. Yet not all birds can fly. For example, ostriches and penguins are flightless. Instead of flying, ostriches walk or run. They use their wings only for balance and to attract mates. Penguins swim. They use their wings as flippers.

Loading the player...Penguins

People have always been fascinated by birds. Birds’ marvelous flying ability makes them seem the freest of all animals. Many birds have gorgeous colors or sing sweet songs. The charms of birds have inspired poets, painters, and composers. Certain birds also serve as symbols. People have long regarded the owl as a symbol of wisdom and the dove as a symbol of peace. The eagle has long represented political and military might.

Bald eagle

There are about 9,700 species (kinds) of birds. The smallest bird is the bee hummingbird, which grows only about 2 inches (5 centimeters) long. The largest living bird is the ostrich, which may grow up to 8 feet (2.4 meters) tall. The largest bird that ever lived was the elephant bird, which died out hundreds of years ago. It weighed about 1,000 pounds (450 kilograms). Birds inhabit all parts of the world, from the polar regions to the tropics. They are found in forests, deserts, and cities; on grasslands, farmlands, mountaintops, and islands; and even in caves. Some birds, including albatrosses and certain ducks, always live near water. Most such birds can swim. Other birds, especially those in the tropics, stay in the same general area throughout life. Even in the Arctic and the Antarctic, some hardy birds stay the year around. But many birds of cool or cold regions migrate each year to warm areas to avoid winter, when food is hard to find. In spring, they fly home again to nest.

All birds hatch from eggs. Among most kinds of birds, the female lays her eggs in a nest built by herself or her mate or by both of them. The majority of birds have one mate at a time, with whom they raise one or two sets of babies a year. Some birds keep the same mate for life. Others choose a new mate every year. Most baby birds remain in the nest for several weeks or months after hatching. Their parents feed and protect them until they can care for themselves. Other kinds of baby birds, including chickens and ducks, become active and able to walk and feed themselves soon after hatching. Most birds leave their parents after only a few months.

Birds belong to the large group of animals called vertebrates. Vertebrates are animals with a backbone. The group also includes fish, reptiles, and mammals. Birds have two forelimbs and two hindlimbs, as do cats, frogs, lizards, and many other vertebrates. But in birds, the forelimbs are wings rather than arms or front legs. Like mammals, and unlike amphibians and reptiles, birds are warm-blooded—that is, their body temperature always remains about the same, even if the temperature of their surroundings changes. Unlike most other vertebrates, living birds lack teeth. Instead, they have a hard bill, or beak, which they use in getting food and for self-defense. A number of the earliest birds possessed teeth, but these species no longer exist.

Many birds have great value to people. Such birds as chickens and turkeys provide meat and eggs for food. Some kinds of birds help farmers by eating insects that attack their crops. Others eat farmers’ grain and fruit. But in general, birds do much more good than harm.

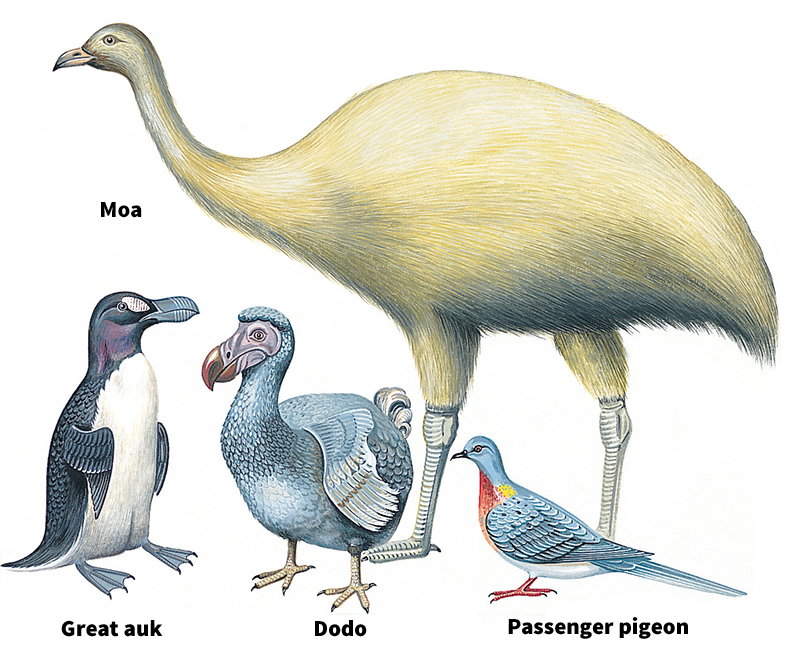

Since the 1600’s, about 80 kinds of birds have died out. People have killed off most of these species by overhunting them and by destroying their environment. Today, most countries have laws to protect birds and help prevent any more kinds from dying out.

This article discusses the importance of birds, their distribution throughout the world, how they live, and how they raise a family. The article also describes bird migration, the bodies of birds, bird study and protection, and the evolution of birds.

The importance of birds

In nature.

Each species of animal in a woodland, grassland, or other natural area depends on other living things in the environment for food. In a woodland, for example, some birds get their food mainly from plants. Others chiefly eat small animals, such as insects or earthworms. Birds and bird eggs, in turn, serve as food for such animals as foxes, raccoons, and snakes. The feeding relationships among all the animals in an environment help prevent any one species from becoming too numerous. Birds play a vital role in keeping this balance of nature. See Balance of nature.

Birds also serve other purposes in nature. Fruit-eating birds help spread seeds. The birds eat and digest the pulp of berries and other fruits but pass the seeds in their droppings. The seeds may sprout wherever the droppings fall. Hummingbirds pollinate certain flowers that produce nectar. Hummingbirds feed on nectar. As they visit flowers in search of it, they carry pollen from flower to flower. In these ways, birds help numerous kinds of plants reproduce and spread.

Hummingbirds

Many kinds of birds assist farmers by eating weed seeds, harmful insects, or other agricultural pests. Unlike birds that feed on fruits, seed-eating birds digest the seeds they eat. One bobwhite may rid a field of as many as 15,000 weed seeds a day. Many birds eat insects that damage farm crops. Some birds are especially helpful in keeping the number of certain kinds of insects under control. Robins and sparrows, for example, are highly effective against cabbageworms, tomato worms, and leaf beetles. Rats and mice can cause huge losses on farms by eating stored grain. Hawks and owls prey on these animals and so help limit such losses.

People consider a few kinds of birds to be pests. One such species, the common, or European, starling, was introduced into the northeast United States in the 1890’s. The birds multiplied and spread rapidly. Today, starlings are so numerous in many North American cities that they have become a nuisance because of their noise and droppings. Moreover, starlings fight with certain native American birds, including bluebirds and swallows, over the tree holes in which they nest. Pigeons are also a nuisance in many cities because of their droppings. Flocks of starlings and pigeons leave masses of droppings on buildings where the birds have been roosting. The fungus Histoplasma capsulatum can grow on these droppings. The spores of the fungus may be carried in the air and cause the infectious disease histoplasmosis in people who inhale them (see Histoplasmosis). Some strains of influenza, another infectious disease, can be passed to human beings from infected domestic birds, including chickens and ducks. West Nile virus, which causes a flulike disease, is transmitted from infected birds to human beings and other animals through the bites of mosquitoes (see West Nile virus).

As a source of food and raw materials.

People have always hunted birds for food. Some of the first birds used for food were ground-feeding birds, such as quails and turkeys, which were caught in traps and snares. Hunters captured pigeons, ducks, and other birds by placing nets where the birds normally flew. After the invention of guns, most people hunted large, meaty birds to save gunpowder and shot. The eggs of wild birds were also an important food for people in prehistoric times, and people in some parts of the world still eat such eggs. Because most birds’ nests are hard to find, the eggs used for food have come chiefly from sea birds that nest in open places in large colonies (groups).

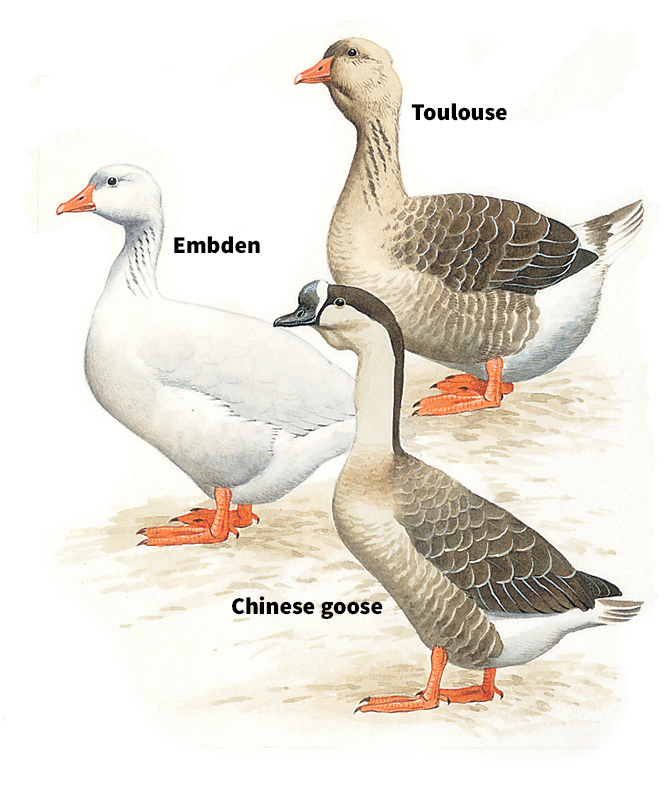

People eventually discovered that certain wild fowl could be domesticated (tamed). This discovery led to the development of poultry—that is, domesticated fowl that farmers raise for meat and eggs. Chickens are probably the oldest kinds of poultry. They were domesticated in Asia thousands of years ago. Since then, farmers have developed other poultry, including ducks, geese, guineafowl, pheasants, and turkeys. Mallard ducks, geese, and pheasants were domesticated in Asia; guineafowl in Africa; and Muscovy ducks and turkeys in Mexico.

Today, chickens rank as the most widely raised poultry by far. Farmers throughout the world produce hundreds of millions of chickens annually for meat and eggs. Ducks and turkeys rank second and third in production worldwide. Ducks are raised for both meat and eggs. Turkeys are raised mainly for meat.

People use the feathers of certain birds to stuff pillows, mattresses, sleeping bags, coats, and quilting. Goose feathers are preferred because they are soft and springy. Manufacturers often mix goose feathers with down feathers, or down, to provide extra softness. Down feathers are small, fluffy feathers that some adult birds, especially water birds, have between their stiffer outer feathers. Most of the down used for stuffing comes from ducks and geese raised on farms.

People throughout the world use colorful bird feathers to decorate jewelry, clothing, and hats. Many countries forbid the use of feathers from wild birds. People may only use feathers from domesticated birds, such as turkeys, or from other birds raised in captivity, such as peacocks and pheasants.

Over the centuries, the droppings of ocean birds have formed huge deposits on certain islands where the birds nest in dry areas. This waste matter, which is called guano, provides an excellent source of nitrogen that people use to make fertilizer and explosives. The mining of guano for fertilizer was once an important industry in some countries.

As pets.

People have long kept birds as pets. Favorite bird pets include canaries, parrots, finches, and parakeets called budgerigars, or “budgies.” Budgies and parrots are especially popular because they can be trained to imitate human speech and even to whistle.

Most birds sold as pets have been raised in captivity. The birds are hatched in cages and sold to the public by pet stores. After years or centuries of captive breeding, some of these birds look much different from their wild ancestors. For example, wild budgerigars are green, but breeders have produced white, yellow, blue, and even violet budgerigars. In the past, most of the parakeets and parrots sold as pets were caught in the wild. Over the years, this practice wiped out some species. To help protect such birds, many countries have made it illegal for wild birds to be caged except in zoos. However, many wild parakeets and parrots are still captured and sold illegally throughout the world.

The distribution of birds

Every species of bird has its own range—that is, a particular part of the world in which all the members of the species normally live. Some birds have a broad range. The osprey and common barn owl, for example, live on every continent except Antarctica. However, no species of bird is found in every part of the world, and many species have an extremely limited range. For example, a species called the Whitehead’s broadbill lives only in a small, mountainous area of northern Borneo.

Oceans and continents strongly influence the distribution of various species of birds. Most birds cannot make long ocean flights. Widely separated continents, such as Africa and North America, therefore have different kinds of birds. However, people have transported many species overseas, and some of these birds have become adapted to their new environment.

Climate also influences a bird’s range. Most birds would starve during a long cold spell. For this reason, few birds live all year in regions with severe winters. However, many birds nest in such regions in summer and migrate to warmer climates for the winter. Birds that migrate have two ranges—a summer one and a winter one. They are summer residents in their summer range and winter residents in their winter one. Along their migration route, they are transients (temporary visitors). Birds that do not migrate are permanent residents.

More kinds of birds live in the tropics than anywhere else in the world. Tropical rain forests have more kinds of birds than any other habitat. Most birds of the tropics are permanent residents. However, some parts of the tropics have an annual dry season, and many of the birds migrate to moister parts of the tropics to avoid it. The tropics also have many winter residents that migrate from cool or cold climates. The temperate zones—that is, the parts of the world between the tropics and the polar regions—have fewer permanent residents than do the tropics. In the parts of the temperate zones nearest the polar regions, most of the birds are summer residents only. Few birds live all year in the polar regions. However, both the Arctic and the Antarctic have many residents during the summer.

The ranges of birds are further determined by the kinds of food and nesting places that are available. For example, fish-eating birds must live near bodies of water. Birds that nest in trees normally live only in wooded areas. Thus, most birds live not only in a particular region of the world but also in a particular type of environment, or habitat, within that region.

Birds of North America

Hundreds of species of birds live in North America north of Mexico, a region that includes all of Canada and all of the United States except Hawaii. Most of this region lies in the northern temperate zone. In the southern part of the region, many of the birds are permanent residents. In the northern part, most of the birds are summer residents only. In summer, the birds mate, lay and hatch their eggs, and raise their families. They then fly south for the winter. Mexico and Central America are part of North America. But most of the birds that reside there permanently are more closely related to those of South America than to U.S. and Canadian birds.

Loading the player...Great horned owl

The birds of temperate North America live in seven main kinds of habitats: (1) urban areas, (2) forests and woodlands, (3) grasslands, (4) brushy areas, (5) deserts, (6) inland waters and marshes, and (7) seacoasts. Some North American birds live north of the temperate zone—that is, in the Arctic.

Birds of urban areas

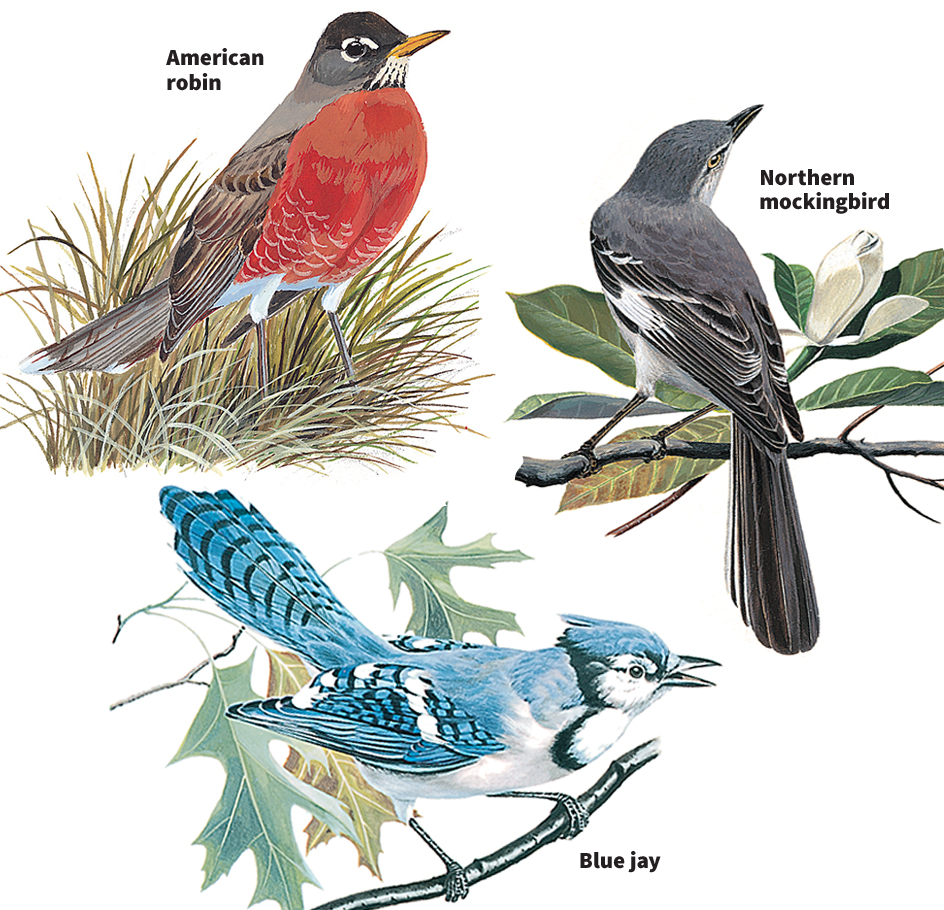

Many birds will nest in urban areas if these areas have nesting places similar to those of the birds’ natural habitat. In addition to pigeons and starlings, such birds include robins, blue jays, mockingbirds, cardinals, wrens, common crows, grackles, and house sparrows. Cardinals and mockingbirds usually nest in shrubs or low trees. Robins and blue jays nest in shade trees. Wrens nest inside tree holes, bird boxes, and even mailboxes. House sparrows and pigeons, both introduced from Europe, rank among the most common birds in North American cities. They will nest in almost any small opening. Such birds remain a familiar sight even in the downtown areas of big cities.

Birds of forests and woodlands

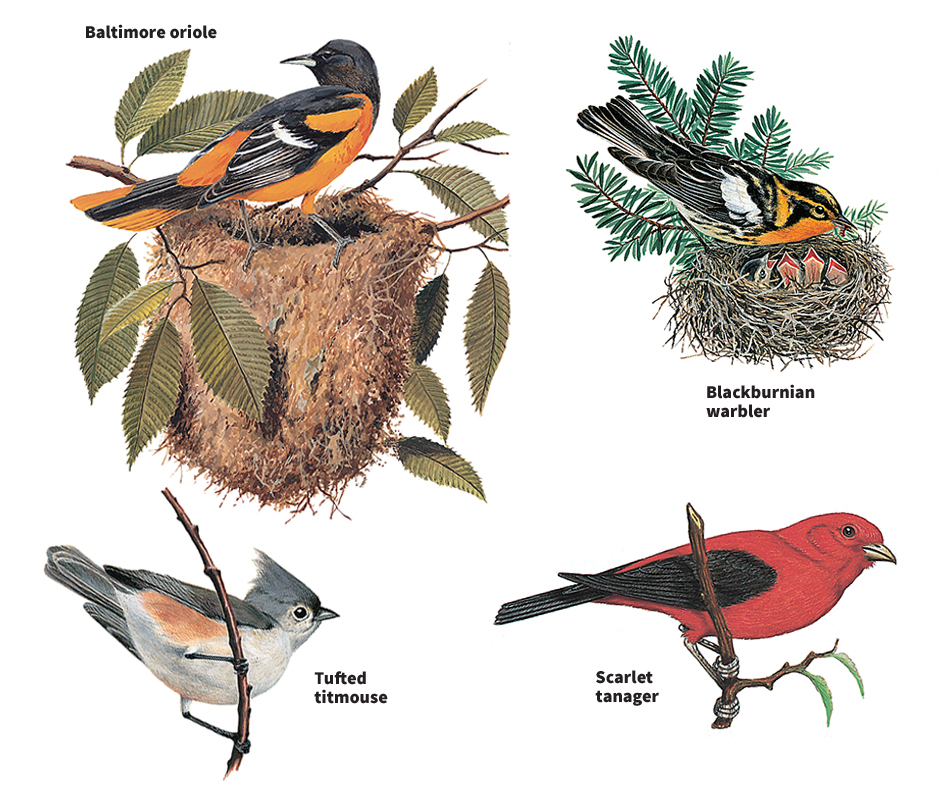

Some North American birds live chiefly in needleleaf forests—that is, forests in which the dominant trees have narrow, needlelike leaves, such as firs, pines, and spruces. Needleleaf forests cover much of Canada and Alaska and mountainous areas of the western United States. Typical birds of these forests include the Blackburnian warbler, common creeper, gray jay, red-breasted nuthatch, ruby-crowned kinglet, and winter wren.

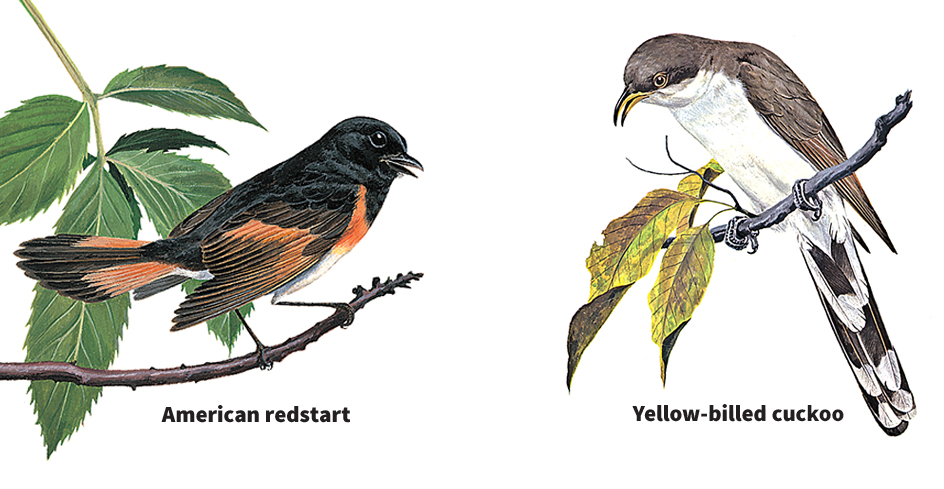

Certain other birds live chiefly in forests of broadleaf trees, which have broad, flat leaves that fall off each autumn. Such trees include the ash, beech, elm, maple, and oak. Broadleaf forests grow mainly in the eastern half of the United States and southeastern Canada. Typical birds of these forests include the American redstart, Baltimore oriole, ovenbird, scarlet tanager, tufted titmouse, and white-breasted nuthatch. Some birds, such as the hairy woodpecker and yellow-bellied sapsucker, inhabit both needleleaf forests and broadleaf forests.

Certain birds prefer open woodlands to dense forests. Open woodlands are areas of scattered trees. They are found mainly on the edges of forests, along riverbanks, and in suburban areas. Birds that nest in open woodlands include the cedar waxwing, downy woodpecker, house wren, rose-breasted grosbeak, yellow-billed cuckoo, and northern flicker. Red-eyed vireos live in almost any area that has broadleaf trees.

Many birds inhabit a particular level of a forest or woodland. For example, grosbeaks, tanagers, and many kinds of wood warblers live mainly in the treetops. Nuthatches and woodpeckers live farther down on the branches and trunks. Ovenbirds and winter wrens live chiefly on the forest or woodland floor.

Birds of grasslands

Until the mid-1800’s, prairies covered much of central North America. The tall prairie grasses were a favorite nesting place of many birds. Today, most prairies have been plowed under for use as cropland. The birds that have adjusted best to these changes are those that traditionally nest in other open areas in addition to prairies. Such birds include the American kestrel, dickcissel, horned lark, vesper sparrow, western kingbird, and western meadowlark. Today, these birds nest as readily in or near hayfields and other cultivated grasslands as they do in native prairies. Horned larks even nest on golf courses.

Some prairie birds have had great difficulty adjusting to the changes in their habitat. For example, prairie-chickens once ranked among the most numerous prairie birds. But prairie-chickens nest only among tall grasses. Today, they live only in the few remaining native prairies.

Dry grasslands, now used mostly for grazing cattle, cover much of the western parts of the United States and Canada. Birds that nest in these grasslands include the burrowing owl, lark bunting, scissor-tailed flycatcher, and Baird’s sparrow. Except for the burrowing owl, these birds have fared better than many of the prairie birds because their nesting places have been less disturbed by agriculture. Burrowing owls traditionally nest in prairie dog burrows. Ranchers have regarded prairie dogs as pests, however, and have tried to destroy their burrows. In so doing, they have wiped out the nesting places of the owls.

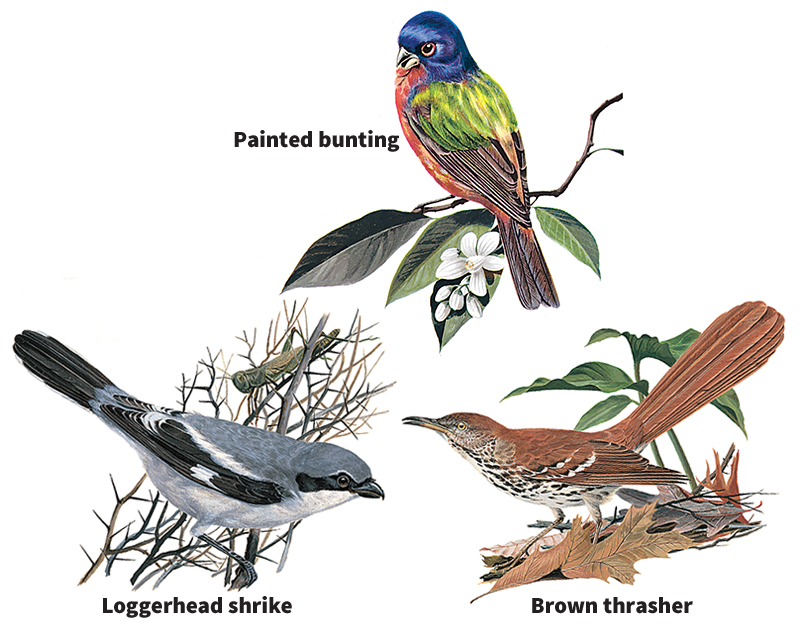

Birds of brushy areas

Some birds make their home in and around brushy areas, which are covered by bushes and low scrubby trees. Such areas commonly occur on the edges of forests and woodlands, between woodlands and grasslands, and in abandoned fields that are developing into woodlands. Brushy areas exist throughout the United States and southern Canada. Many of the birds that live in these habitats are also wide ranging. They include the eastern towhee, gray catbird, loggerhead shrike, rufous-sided towhee, and yellow-breasted chat. Other birds of brushy habitats have a more limited range. The bobwhite and Carolina wren are permanent residents in the southeastern United States and in Mexico. The painted bunting nests chiefly in the southeastern half of the United States but migrates to Mexico in winter.

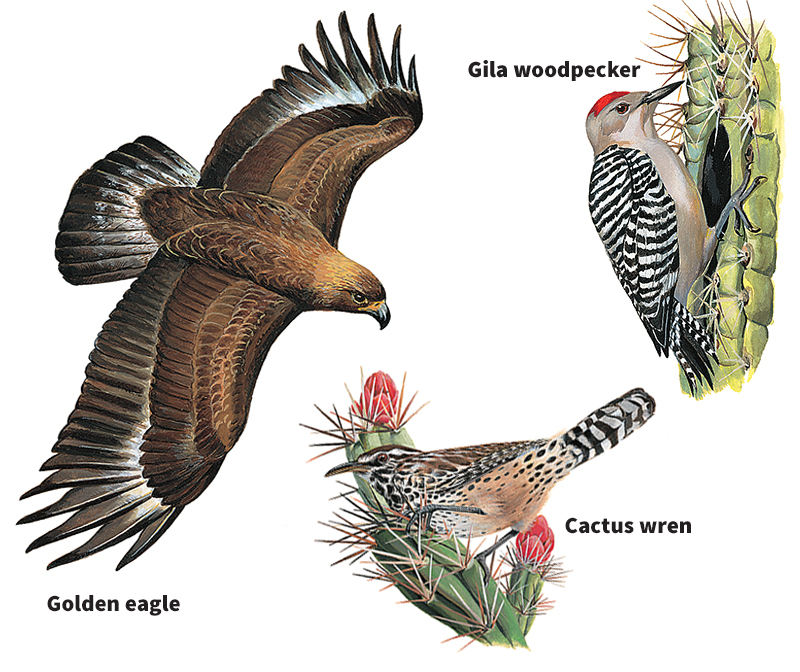

Birds of the desert

Many birds that live in the deserts of the southwestern United States nest in saguaros and other large cactuses. The cactus wren builds its nest among cactus spines. Gila woodpeckers and gilded flickers nest in holes that they make in cactus stems. Elf owls, the smallest owls in the world, nest in holes that the woodpeckers abandon. A large percentage of desert birds chiefly eat animal flesh or insects. The deserts are dry, and such a diet provides more moisture than a diet of seeds. Meat-eating birds, including the golden eagle, roadrunner, and various species of owls, rank among the most common desert birds. Most of the cactus dwellers mainly eat insects. Gambel’s quail and several species of sparrows are among the few ground-nesting, seed- eating birds of the North American deserts.

Birds of inland waters and marshes

Most water birds swim after their food or dive or wade into the water for it. Few water birds live near fast-moving rivers because swimming, diving, and wading are difficult in a strong current. Lakes, ponds, and marshes are the chief freshwater habitats of birds. The birds nest on the shores of lakes and ponds and on high ground in marshes.

Typical swimming and diving birds of U.S. and Canadian fresh waters include the American coot, California gull, common loon, horned grebe, king rail, and many kinds of ducks. Among the ducks are the American wigeon, blue-winged teal, canvasback, and shoveler. Although some of these birds are excellent swimmers, a number of them feed mostly by wading at the edge of the water. Common wading birds include the American bittern, common snipe, great blue heron, and spotted sandpiper.

Some land birds have adopted ways of life that keep them near water. For example, the marsh wren, common yellowthroat, and red-winged blackbird often nest in marshes. The Louisiana waterthrush nests on the banks of streams and feeds on water insects. Belted kingfishers perch alongside bodies of water. Kingfishers dive after fish that swim near the surface and catch them with their bills.

Some birds of inland waters and marshes also live in saltwater environments. For example, the belted kingfisher, great blue heron, and green-backed heron often nest near the ocean and hunt fish in the shallow coastal waters. Most water birds of the United States and Canada fly south for the winter. Many of these birds make their winter homes near salt water.

Birds of the seacoasts

Some American and Canadian water birds normally nest along seacoasts. Along the Atlantic coast, such birds include the American oystercatcher, black skimmer, and common tern. The black oystercatcher, western gull, and Cassin’s auklet nest along the Pacific coast. The brown pelican, laughing gull, and Wilson’s plover nest along both coasts. Some species, such as oystercatchers and plovers, are shore birds. Certain others, including auks and auklets, gulls, and terns, sometimes hunt fish far out at sea.

In winter, the southeast, south, and southwest coasts of North America provide homes to numerous ducks, geese, and many other birds that nest in the Arctic. Many sandpipers and other Arctic birds visit U.S. and Canadian shores en route to winter homes in the tropics.

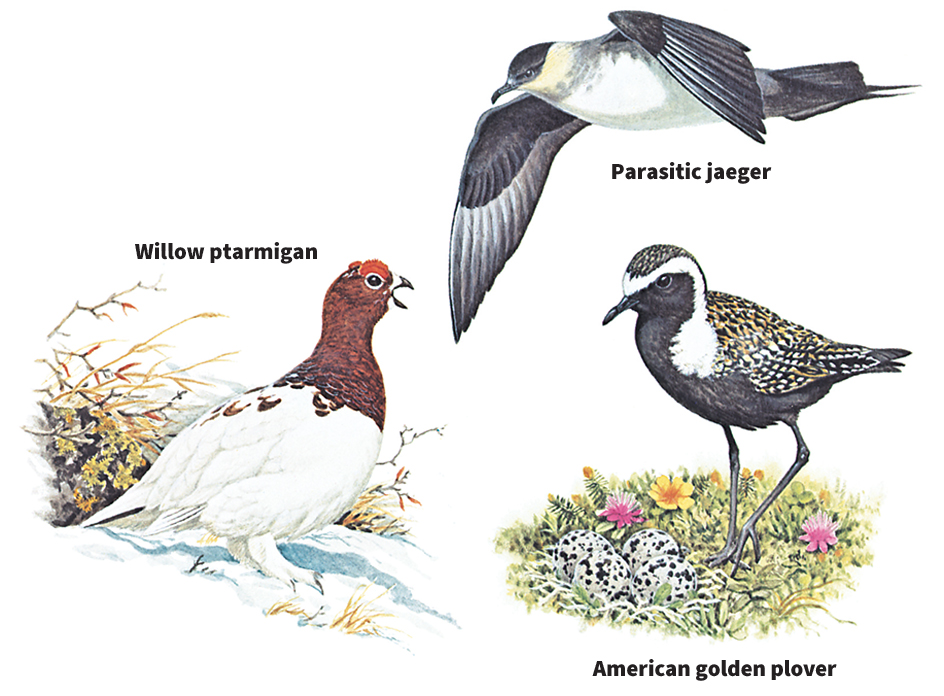

Birds of the Arctic

Northernmost North America, Asia, and Europe lie in the Arctic. Most of this land is tundra—that is, cold, dry, treeless marshland. The Arctic tundra remains frozen solid most of the year. It comes to life briefly in spring and summer. At that time, the tundra provides a rich source of the insects and other small animals that birds eat. Many birds that winter in warmer climates arrive in the tundra to breed. Most are water birds. They include the American golden plover, Arctic tern, Canada goose, parasitic jaeger, red phalarope, and many species of ducks and sandpipers. Land birds that migrate to the tundra include the horned lark and snow bunting.

Only a few birds live in the Arctic all year. Probably the best known are ptarmigans. These extremely hardy, chickenlike birds survive almost entirely on twigs and leaf buds during the long Arctic winters.

Birds of other regions

Birds of the ocean and the Antarctic

Some birds spend most of their lives far out at sea and seldom visit land except to breed. These birds include albatrosses, gannets, penguins, petrels, shearwaters, and storm petrels. All these birds except penguins are expert long-distance fliers. Penguins cannot fly. But they swim long distances and remain at sea for months at a time. Ocean birds feed by diving for fish, squid, and other small animals. They typically build their nests in crowded colonies. Other birds often hunt far out at sea but return to land regularly. These birds include boobies, frigatebirds, tropicbirds, and the south polar skua.

Many ocean birds nest on Antarctic islands during summer in the south polar region. A few types nest on the ice-covered Antarctic continent itself. These hardy species include the emperor penguin, snow petrel, south polar skua, and Wilson’s storm petrel.

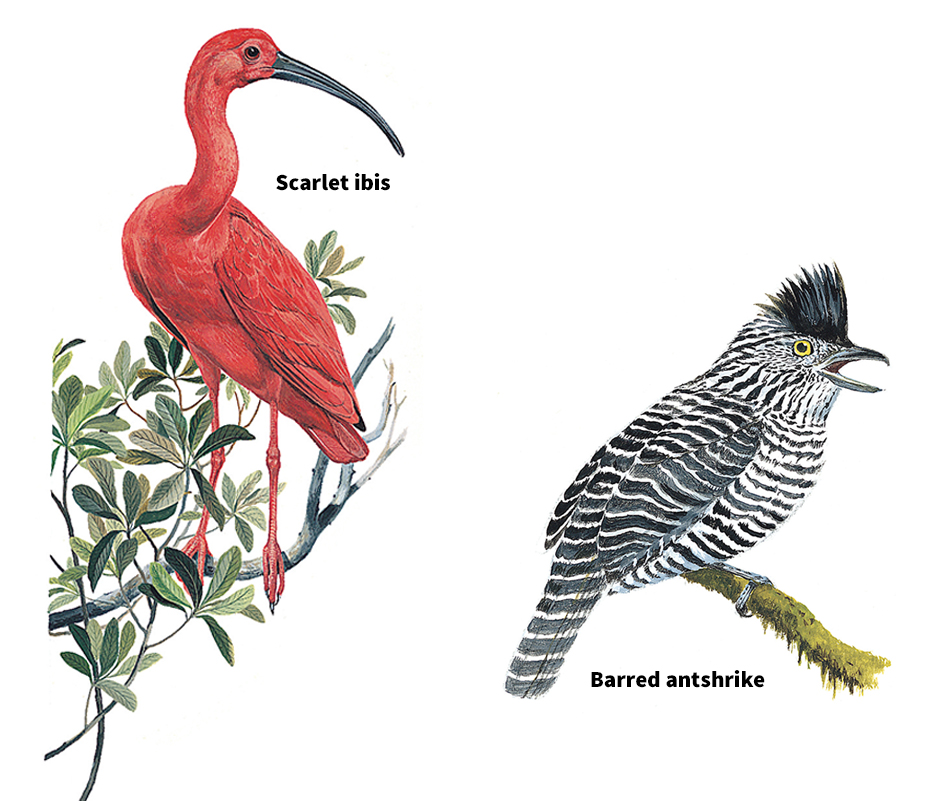

Birds of Central and South America

Central America and most of South America lie in the tropics. The American tropics have more species of birds than does any other area of the same size in the world. Most birds of this region inhabit rain forests. The rest live in grasslands, deserts, dry forests, or near bodies of water. Several of the birds belong to families found nowhere else, including antshrikes, trumpeters, and the hoatzin and sunbittern. Many birds of the region have remarkably colorful plumage, such as the paradise tanager, resplendent quetzal, scarlet macaw, and scarlet ibis. The male Andean cock-of-the-rock performs an elaborate courtship display to attract a mate. The king vulture soars high above the tropical forest, watching for carrion (dead animals) to eat. The keel-billed toucan uses its massive bill to pluck fruit and berries. It also eats insects, reptiles, and some baby birds.

Birds of Europe

Europe encompasses a wide range of habitats, from the Arctic in the far north; through the northern needleleaf forests, where many firs and spruces grow; to mixed woodland and dry Mediterranean maquis (scrub).

Many European birds migrate south, mostly to Africa, to escape the cold winters when food is scarce. Migratory species include the European roller, common tern, common cuckoo, European bee-eater, Eurasian hobby, bluethroat, swallow, wallcreeper, and white stork. The hobby, a magnificent flier, preys on such fast-flying birds as swallows and swifts, as well as on such insects as dragonflies. Several of the smaller perching birds, including the common nightingale and the Eurasian skylark, have become well known for their fine songs. The house sparrow and the Eurasian blue tit rank among Europe’s most common birds. The green woodpecker hunts in the trees for insects or tree grubs and on the ground for ants. Goldfinches also inhabit European woodlands. Common water birds include avocets, moorhens, and shelducks. Grassland birds include lapwings and partridges.

Birds of Asia

Asia, the largest of the world’s continents, has a wide variety of climates. These include tropical rain forests, temperate forests, deserts, marshlands, and Arctic tundra. Such birds as broadbills, fairy-bluebirds, fruit-doves, hornbills, and leafbirds inhabit Asian forests. The male rhinoceros hornbill, like other tree-nesting hornbills, walls up his mate into a nest hole while she incubates the eggs. The golden-fronted leafbird lives in monsoon forests, which have a long dry season followed by a season of heavy rainfall. The trees in a monsoon forest usually shed their leaves during the dry season and leaf out again at the start of the rainy season. The golden-fronted leafbird feeds on fruit and insects. The blue-backed fairy-bluebird and the lesser green broadbill eat mainly fruit. Many tropical southeast Asian birds, such as the blue-winged pitta and purple-throated sunbird, have multicolored plumage.

Loading the player...

Golden-fronted leafbird

The Himalaya, the great mountain range in southern Asia, is a biologically rich area with many species of birds. The foothills of the Himalaya provide a home to several brightly colored members of the pheasant family, including the Himalayan monal and Lady Amherst’s pheasant. The Himalayan monal lives in forests above 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) high. The male has a loud ringing call. The common myna inhabits dry hillsides in India.

Some cultivated areas of Asia have become habitats for such species as the coppersmith barbet and the Java sparrow. The coppersmith barbet lives in open woodland, including orchards and gardens. It has a distinctive, monotonous “tonk” call, which it repeats over long periods. The Java sparrow was originally native to the islands of Bali and Java but has been widely introduced to other regions. It commonly resides in open areas, including rice fields, and has become a popular pet.

Birds of Africa

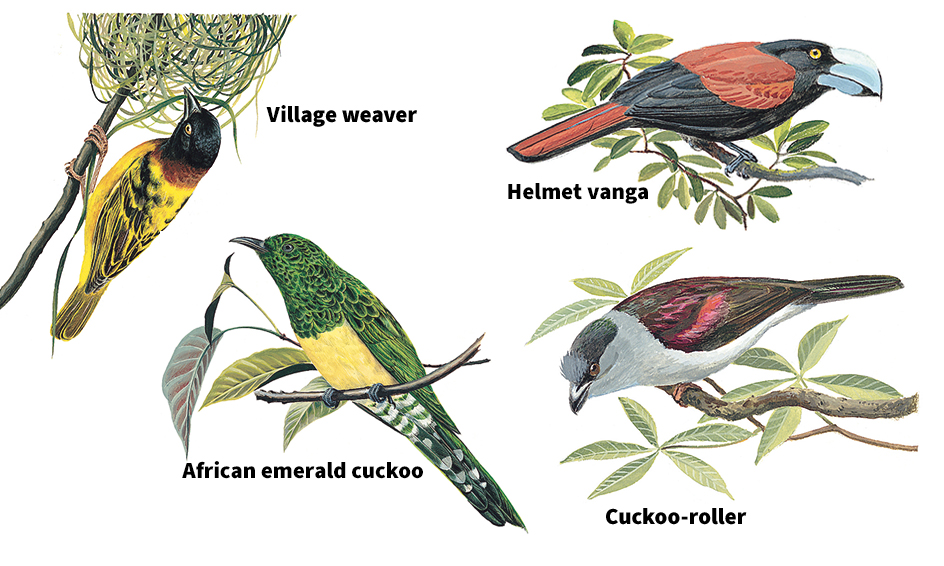

The Sahara, a vast desert, stretches across northern Africa and separates the continent’s northern Mediterranean coastline from the land to the south. As a result, Mediterranean Africa shares many bird species with southern Europe. South of the Sahara, much of Africa has a tropical climate and a richer bird life. Rain forests provide homes for such colorful birds as the emerald cuckoo, yellow-bellied wattle-eye, and hamerkop. Many kinds of weavers live in open woodlands. The tropical grasslands have two of the world’s tallest birds, the ostrich and the secretarybird, as well as guineafowl and the crowned crane. Water birds of tropical Africa include the shoebill, the African fish-eagle, and various ducks, jacanas, kingfishers, and pelicans. Madagascar, a large island off the southeast African coast, has many unique birds, including the cuckoo-roller and the helmet vanga.

Birds of Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand boast a rich variety of birds. Australian birds include the superb lyrebird with its elaborate tail feathers, as well as the bell miner, brolga, eastern spinebill, grey butcherbird, Gouldian finch, spotted pardalote, superb fairy-wren, white-plumed honeyeater, and willie-wagtail. The wedge-tailed eagle ranks as one of the world’s largest eagles. It feeds on mammals, reptiles, and other birds, and it can even tackle prey as large as young kangaroos. The laughing kookaburra, a kind of kingfisher, occasionally eats fish. But its normal diet consists of reptiles, small mammals, birds, caterpillars, insects, and worms.

Prominent New Zealand birds include the flightless kiwi, a relative of the ostrich, as well as the noisy kākā and the colorful tūī. Native bellbirds and pigeons also live in this island nation.

Birds of the Pacific Islands

Most of the Pacific Islands have relatively few bird species. But many of these birds live nowhere else.

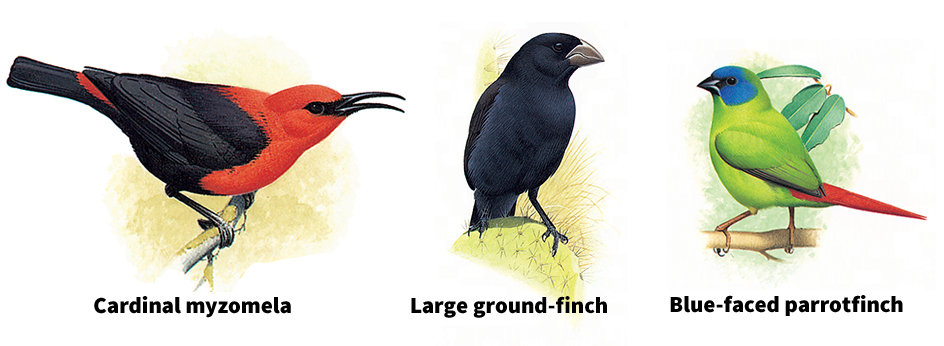

The nene, or Hawaiian goose, was rescued from the brink of extinction and reintroduced to Hawaii. The cardinal myzomela lives in scrub and woodland on Vanuatu, Samoa, Santa Cruz, and the Solomon Islands. The large ground-finch of the Galapagos Islands belongs to the group of finches studied by the British naturalist Charles Darwin when he developed his theory of evolution (how living things change over time). The almost flightless kagu of New Caledonia has become endangered, partly because it is threatened by cats, dogs, rats, and other predators introduced to the island by people. The 10 subspecies of blue-faced parrotfinches inhabit Australia and such Pacific islands as Vanuatu and the Solomon Islands. The rare blue lorikeet lives mostly on a few atolls (ring-shaped coral islands) in the Society Islands of French Polynesia.

How birds live

To survive as individuals, birds must obtain enough food and water and must defend themselves against predators. These activities require skills of movement, such as flying or swimming, and certain communications abilities. To survive as a species, each generation of birds must produce and raise offspring.

Most small birds from temperate climates live only a few years at most. Many birds die of hunger, disease, injury, exposure to bad weather, or the risks of migration. Numerous others are killed by predators (animals that prey on other animals). In spite of all the dangers they face, some birds manage to complete their normal life span. In general, big birds live longer than small ones. For example, albatrosses may live 40 years or more, but wrens are unlikely to survive as long as 15 years.

Birds generally have a better chance for survival in captivity than in the wild. As a result, the age records for most species are held by birds raised in zoos or as pets. The recordholders include an eagle owl that lived to age 68 in a zoo and a pet parrot that lived to age 70.

How birds get food

Birds have a higher body temperature than mammals. They therefore require more food in relation to their size than do mammals to maintain the higher temperature. In addition, small birds must eat relatively more than large ones because their bodies use up food energy faster. A tiny bird, such as a kinglet, may eat a third of its weight in food each day. A larger bird, such as a starling, may eat only about an eighth its weight. The amount that birds eat also depends on what they eat. For example, a given amount of nectar provides more energy than the same amount of seeds. A nectar-eating bird thus needs less food than a seedeater of the same size. Large birds can go several days without food. Small birds may spend most of their time eating. To survive a cold night, in fact, some small birds must burn off the body fat they have stored from food eaten earlier that day.

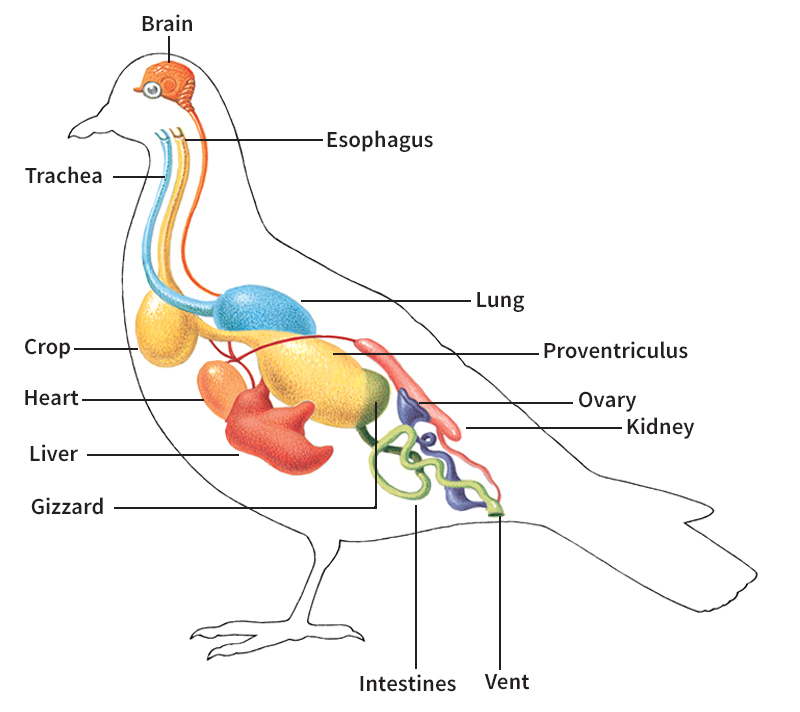

Like all other animals, birds must regularly replace the water that their bodies lose. However, birds do not produce such fluid wastes as sweat and urine. They lose only a small amount of moisture in their droppings and when they exhale. Birds therefore require less water than do many other animals. Birds that eat juicy foods, such as nectar or insects, may get all or most of the water they need in their food and may seldom have to drink. Some birds, including the hummingbirds and sunbirds that feed on flower nectar, consume much more water than they actually need. Nearly all birds drink water by scooping it up in their bill, tilting the head back, and letting the drops trickle down the throat.

Kinds of food.

Birds mainly eat insects, fish, meat, seeds, and fruits. Many bird species prefer one type of food, while others consume a wide variety.

Many birds live largely on insects. Insect eaters include creepers, flycatchers, kinglets, nightjars, swallows, swifts, thrashers, titmice, vireos, warblers, woodpeckers, and small hawks and owls. Some insect eaters also feed on spiders and earthworms. Fish-eating birds include cormorants, grebes, herons, kingfishers, loons, ospreys, pelicans, and terns. Many fish eaters also feed on other water animals, such as crabs and snails. Meat eaters, or birds of prey, live on the flesh of other birds, reptiles, and small mammals. The chief birds of prey include caracaras, eagles, falcons, hawks, owls, and vultures. Most of these birds hunt and kill their prey themselves. A few birds of prey eat mainly carrion—that is, the decaying flesh of dead animals. Vultures and caracaras are the chief carrion eaters.

Birds that feed mainly on seeds include buntings, finches, grosbeaks, pigeons, and sparrows. Most fruit-eating birds dwell in the tropics, where fruits are plentiful the year around. These birds include cotingas, hornbills, manakins, parrots, tanagers, and toucans. In cooler climates, many birds feed on fruits when available and on insects or seeds the rest of the year. Such birds include catbirds, mockingbirds, robins, and waxwings. Birds also get other food from plants besides fruits and seeds. Honeyeaters and hummingbirds live mainly on nectar from flowers. Sapsuckers often feed on tree sap. Ducks, geese, and swans eat all kinds of vegetable matter, including grass and seaweed.

Although most species prefer a certain food, fish eaters and meat eaters are among the few birds that live on only one kind of food. Most insect eaters also eat seeds or fruits, and most birds that feed on seeds or fruits feed their young primarily insects. A few birds eat almost any food they can find, even garbage. These birds include crows, gulls, ravens, and starlings.

Feeding methods.

In most cases, the structure of a bird’s bill or feet—or of its bill and feet—is adapted to its method of feeding. For example, birds of prey have sharp claws for seizing small animals and a hooked, razor-edged bill for tearing off flesh. The section The bodies of birds discusses such adaptations.

Some birds have developed highly specialized or unusual feeding methods. Swifts and swallows catch insects in flight by using their long, narrow wings to make fast aerial maneuvers and their extra-wide mouths to capture the insects. Hummingbirds can beat their wings in a circular fashion and so can hover in the air, like a helicopter. Hummingbirds use this skill to hover in front of flowers and collect nectar. They can also fly backward and so back their long bills out of a blossom. This method of feeding requires a lot of energy, so an active hummingbird uses more calories (units of energy) for its body weight than does any other vertebrate animal.

Some birds depend on other animals to help them get food. Cattle egrets and cowbirds follow herds of grazing animals and feed on insects startled by the animals’ hoofs. Bald eagles, frigatebirds, jaegers, and skuas often steal fish from other birds. Honeyguides, which are found mainly in Africa, live largely on beeswax. The birds cannot get at the wax by themselves. Instead, they use loud calls to lead people and other mammals to beehives. These mammals open the hives and eat the honey. The birds then feast on the wax and the bee larvae.

How birds move

Birds move from one place to another chiefly by flying. Only a few kinds cannot fly. Some of these flightless birds are cassowaries, emus, kiwis, ostriches, rheas, and penguins. Most birds also can move about on land. The chief exceptions are grebes, loons, hummingbirds, kingfishers, and swifts. The legs of grebes and loons are so far back on the body that the birds can barely walk or even stand. On land, they can barely push themselves along on their belly. However, their legs are ideally positioned for underwater swimming. The legs and feet of hummingbirds, kingfishers, and swifts are suited to clinging or perching but not to walking. These birds can move from place to place only by flying.

Many birds can swim, as well as fly and move about on land. Some birds swim by paddling with their legs, such as ducks, loons, cormorants, and grebes. Others swim by flapping their wings as if in flight under water. These underwater flyers include penguins, auks, puffins, murres, and diving petrels. Some of the best swimmers, such as penguins and loons, are handicapped in other movements. Penguins cannot fly, and loons cannot walk.

Loading the player...How birds fly

In the air.

A bird’s wing is curved on top and flat or slightly curved on the bottom. When air moves rapidly past a wing of this shape, the air flows faster over the curved top surface than over the flatter bottom surface. The flow of air over the wing produces an upward force called lift. Lift enables birds to overcome gravity, rise, and remain airborne.

Experts disagree on the best explanation of lift. According to one explanation, the faster airflow over the wing’s top surface reduces the air pressure above the wing. Air pushes more strongly against the bottom of the wing, producing lift. Another explanation is related to the wing’s ability to deflect (turn) the airflow downward. As the air is forced downward, the wing is pushed upward, producing lift. See Aerodynamics (Lift).

Birds launch themselves into the air by using their leg muscles to push against a perch or to jump from the ground or water. Some water birds, such as coots and sea ducks, paddle rapidly and flap their wings until they gain enough speed to become airborne. During flight, the tips of a bird’s wings not only flap up and down but also twist forward on the downstroke and flatten on the upstroke. This twisting motion produces forward thrust and propels the bird forward. The rest of the wing remains level in relation to the flow of air, providing lift. Similarly, helicopter blades change angle twice in each rotation to produce lift and thrust from the moving blades.

After take-off, some birds continue to fly mainly by flapping their wings. Others combine flapping flight with gliding or soaring. In gliding, birds keep their wings extended and coast downward through the air, using little energy. In soaring, birds use the energy of air movements to propel themselves without having to flap their wings. They may use wind, heated rising air called thermals, or the lift of air along a cold front.

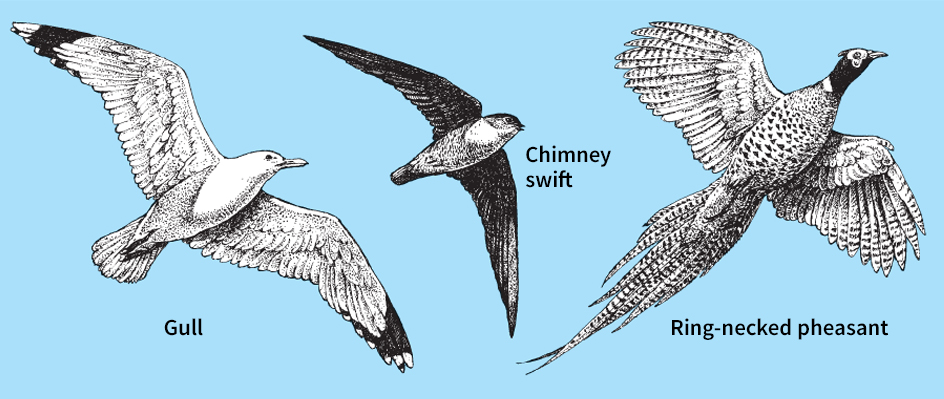

The majority of small birds depend on flapping flight. In most cases, their cruising speed averages about 20 to 35 miles per hour (mph), or about 32 to 56 kilometers per hour (kph). Most fast fliers are large birds with long, pointed wings. The peregrine falcon has been clocked at speeds over 200 mph (320 kph) while diving. Many soaring birds are large ocean birds that have long, pointed wings. Examples of such birds include albatrosses, frigatebirds, gulls, ospreys, shearwaters, and tropicbirds. Ocean soarers take advantage of the frequent strong winds near the surface of the world’s oceans. Soaring land birds include hawks, eagles, and vultures. Unlike the ocean soarers, soaring land birds have long, but broad, rounded wings. Many wild fowl, such as pheasants and quail, have short, broad, rounded wings. Birds with such wings can take off suddenly and fly at high speeds for a short distance. These birds seldom make long flights, however.

Hummingbirds, kestrels, and terns are among the few kinds of birds that can hover in flight. In addition, hummingbirds are the only birds that can fly backward.

On land.

Birds move about on land by running, walking, hopping, and climbing. The big flightless land birds can run the fastest. Nearly all of them have extremely long legs. Ostriches, the speediest birds on land, can run as fast as 40 mph (64 kph). Some birds that can fly are also swift runners. These birds include bustards, cariamas, and the secretarybird. Most other birds move more slowly on land.

The majority of birds that nest or feed on the ground walk and run by moving one foot forward at a time, like people. Most species that nest or feed in trees hop about on both feet when on the ground. Some kinds of birds both run and hop. For example, robins often run a short distance and then hop the last few steps before stopping. Some birds are expert climbers, especially those species that climb trees in search of insects. Such birds include creepers, nuthatches, woodcreepers, and woodpeckers. All these birds have short legs and sharp, widely spaced claws, which enable them to cling tightly to the tree while climbing. One such bird, the wallcreeper, uses these claws to climb steep, rocky cliffs and boulders.

In the water.

Many species of birds spend much or most of their time in water. They find food and escape from enemies by swimming or diving. Some of these birds swim mainly on the surface of the water. Such birds include albatrosses, gulls, petrels, phalaropes, and shearwaters. The birds use their legs and feet like paddles to propel themselves through the water.

Certain other birds swim underwater as well as on the surface. Most underwater swimmers, such as cormorants, dive from a floating position on the surface. They give a strong kick, point the head downward, and plunge. Some fish-eating birds, including kingfishers and terns, dive into the water from high in the air. They do not swim but bob to the surface and fly away. Most birds use only their legs and feet to swim underwater. However, penguins also use their wings. Grebes can control the depth at which they swim by regulating the amount of air in their lungs and trapped in their plumage. By slowly letting out air, they can gradually submerge themselves until only the head shows above the surface, like a periscope. They can thus swim along unnoticed and watch for enemies at the same time.

How birds communicate

Birds communicate with one another in a variety of ways. Vocal communication by songs and calls ranks as the most important way.

Calls and songs.

Nearly all birds have a voice and use it to call or sing. A call usually consists of a single sound, such as a squawk or peep. A song consists of a series of notes that follow a fairly definite pattern. About half the known species of birds, including nearly all perching species, produce both calls and songs. The majority of other birds, including most water birds and birds of prey, call but do not sing. Pelicans, American vultures, condors, and some kinds of storks are among the few birds that make no vocal sounds.

Loading the player...Pelicans

Birds use their calls mainly as signals to other birds. Baby birds call in one way to tell their parents that they are hungry and in another way to tell them that they are hurt or frightened. Adult birds use certain calls to signal mates and other calls to signal the entire bird community. Calls may warn of approaching danger, often alerting birds of more than one species.

When people think of songbirds, they usually think of canaries, nightingales, and other birds with sweet voices. But some birdsong is not particularly pleasing to human ears. Ravens and waxwings, for example, simply repeat the same unmusical note over and over. In most songbirds, only the males sing. They do so chiefly during the mating season. Each male sings from a series of perches that outlines his territory—that is, the area he claims and defends as his own. His song, which is called an advertising song, has two main purposes: (1) it warns other males of the same species to stay out of the territory, and (2) it attracts a mate. Some birds use different songs for each purpose. To human ears, the songs of all the birds of a particular species may sound alike. But each bird’s voice sounds different to the other members of the species. Even in a crowded colony, parent birds can single out the voices of their chicks, and chicks recognize those of their parents. Ornithologists (bird biologists) and bird watchers learn to distinguish many kinds of birds from their songs alone.

Emperor penguin

Loading the player...

Golden eagle

Birds produce their songs with a unique vocal organ called the syrinx. The syrinx of most birds occurs where the main airway, or trachea, branches into the two smaller air passages, called the bronchi, which go to the lungs. Many birds can produce two different songs at the same time, one with each side of the syrinx. These “two voice” songs include the most beautiful, flutelike songs of the thrushes. Some birds use one side of the syrinx to make lower tones and the other side to make higher tones.

Most birds do not have to learn to make the right vocal calls. In a few groups of birds, however, the young learn many details of their songs from adult members of their species. Birds known to learn their songs include the true songbirds—such as crows, sparrows, thrushes, and warblers—as well as parrots and hummingbirds.

Sometimes a bird makes a “mistake” when it learns a song. Over time, such mistakes in song learning can produce dialects, or regional variations, in the songs within a single species.

Some birds who learn their songs become talented mimics. They not only learn from their own species, but they also imitate the calls and songs of other birds. They can even learn to mimic sounds not originally created by birds, such as dog barks or factory whistles.

One of the most remarkable mimics, the Lawrence’s thrush of tropical South America, can mimic hundreds of species. Mockingbirds and starlings also rank among the most skillful bird mimics. Certain song-learning birds, such as parrots and mynas, become mimics only when kept in captivity. They can then be trained to imitate human speech and even to whistle.

Other means of communication.

Some birds communicate by sounds other than vocal sounds. The loud drumming noise that woodpeckers make on tree trunks with their bill is not the sound they produce when drilling for insects or digging a nest hole. Drumming is their substitute for an advertising song to establish territories and attract mates. Each species of woodpecker has its own drumming rhythms. The male ruffed grouse produces a low drumming sound by beating his wings rapidly. This sound, which carries across long distances, also serves as an advertising song. Male and female storks clatter their bills at one another during their courtship. Some male manakins make snapping sounds with their wings during courtship displays.

Birds communicate almost entirely by sounds in habitats where they may have difficulty seeing one another. Such habitats include thick woodlands and forests. In more open areas, birds also communicate with one another by various kinds of visual displays. For example, they may flash their tail feathers or raise the crest feathers on their head. Like sound communication, sight communication is used in courtship, defending a territory, and signaling danger. Unlike mammals and insects, most birds are not known to communicate with one another using smells. Crested auklets, however, produce a tangerinelike odor during the nesting season. The birds may use this odor to make themselves more attractive to mates.

Other daily activities

Birds spend time every day keeping their feathers in good condition. They also sleep and rest every day. In addition, all birds, except perhaps the largest ones, must constantly be alert to avoid enemies.

Feather care.

A bird cares for its feathers chiefly by cleaning and smoothing them with its beak, a process called preening. A bird uses its feet to preen its head and other hard-to-reach parts. Most birds oil their feathers while preening. A preen gland on the lower back at the base of the tail produces the oil. A bird uses its beak to activate the gland and apply the oil to its feathers. The oil helps keep the feathers waterproof and flexible.

In addition to preening, most birds bathe frequently. Water birds bathe while swimming. Land birds have less efficient preen glands than do most water birds. Their feathers thus become soaked with water more easily. Most land birds wet their feathers only slightly when bathing and then shake them dry as quickly as possible. Other birds practice a form of bathing called dusting. The birds squat on dusty ground and churn up the dust with their feet and wings until their fluffed-up feathers are thoroughly covered. They then stand up and shake the dust off. Scientists do not fully understand the reasons for dusting. It probably helps rid the feathers and skin of lice and other parasites.

Some birds pick up ants with their bill and rub them into their feathers. This process is known as anting. The ants give off a chemical called formic acid, which probably helps eliminate feather mites, another common parasite of birds. Birds have also been observed using anting motions as they rubbed their feathers with such things as cigarette butts, berries, and grasshoppers.

Sleeping and resting.

Most birds search for food during the day and sleep at night. They may also rest and take short naps during the day. Nighttime feeders, such as owls, sleep throughout the day. During the breeding season, most birds sleep in or near their nest. The rest of the time, they sleep on the branches of trees or bushes, on ledges, in holes, or on the bare ground.

Many species of birds sleep while perching on one or both feet. These birds have a locking mechanism in their feet. It makes their toes grip the perch and so prevents the birds from falling. After the nesting season, many kinds of birds sleep together in large groups called roosts. Most roosts congregate in trees, but some form in marshes. Roosts of crows, robins, red-winged blackbirds, or starlings may consist of thousands of birds.

Some swifts, hummingbirds, and nightjars can lower their body temperature before going to sleep in cold weather. They thus conserve energy while sleeping in much the same way as hibernating mammals. Nightjars can hibernate for weeks. Some hummingbirds hibernate every night even though they live in tropical rain forests.

Scientists believe sleep is critical for song learning in birds. The cells of the brain that are responsible for generating the song give off the same signals during sleep as they do when the bird is singing. Biologists think these brain signals show that birds dream of their songs. Such dreaming apparently aids birds in learning songs.

Protection against enemies.

Birds frequently have to protect themselves or their offspring against enemies. Many birds are colored or marked in such a way that they blend with their surroundings. These birds can protect themselves from a predator simply by remaining still and avoiding the animal’s notice. This type of concealment is called protective coloration (see Protective coloration). In other cases, a bird may have to flee or hide—or it may flee and then hide. If all such methods fail, a bird might have to fight.

A bird fights with its beak, legs, or wings—or with all of them—depending on its species. In defending its nest against a predator, a bird often flies at the intruder’s head and calls loudly. However, a bird seldom wins a fight against a predator larger than itself. Among some species of ground-nesting birds, a bird may lure a ground predator away from its nest by dragging one of its wings as if it were broken. An intruder, attracted by what appears to be an injured bird, may be led a safe distance away from the nesting place before the “injured” parent bird flies off.

Family life of birds

Most small and medium-sized birds become sexually mature by the age of 1 year. Larger birds may take two or more years to mature. They can then mate and raise a family. The breeding process usually begins in spring. At that time, the males of most species select a territory and court a mate. The process continues with the building of a nest and the laying and hatching of eggs. The cycle is complete when the offspring mature and prepare to raise families of their own. Adult birds may raise a new family once or twice a year for as long as they live.

Selecting a territory.

A bird’s territory may be small or large. It may contain only the nest, or it may include an area large enough to gather all food for the young. After selecting his territory, a male claims it by singing his advertising song. Gulls, penguins, and other water birds nest in large colonies. But even in the biggest colonies, each male and his mate have their own small territory around their nest. Some birds return to the same nesting site every year.

A male defends a territory chiefly against other males of the same species. In some cases, a warning call or threatening pose is the only defense necessary. But in many cases, the intruder may not leave without a fight.

Courtship and mating.

The relationship between a male and a female bird is known as a pair bond. A pair bond usually forms after a series of courtship displays by the male and a favorable response from the female. Each species has its own displays and responses.

The male’s advertising song is one of the chief courtship displays among songbirds. Males of other species depend more on bright colors or attention-getting movements and postures. Male frigatebirds have a bright-red neck pouch, which they inflate like a balloon. The courtship displays of many species of birds consist of movements of the head, wings, or other body parts. Cranes, grebes, and herons perform elaborate movements. The female’s response may closely resemble the male’s display, and so the two appear to dance together.

Males of some species use leks (small display territories) to attract mates. Some male peacocks and birds-of-paradise, for example, display their elaborate and beautiful plumages within the leks. The males of species that use leks do not participate in nesting or parental care.

Most male bowerbirds build elaborate stick constructions called bowers, which they decorate with colorful objects to impress females. Female birds visit the bowers and choose one mate. After mating, they then leave, build a nest away from the males, and raise the young on their own.

Although the male courts the female in most species, the reverse is true among phalaropes and a few other kinds of birds. In these species, females are more brightly colored than males. The females thus display their plumage to the males, which respond to the females’ advances. Among other birds, including certain species of jacanas, the female claims the territory and may mate with several different males. The males build the nest, care for the eggs, and raise the young while the female defends the territory.

By the end of the courtship period, most adult birds have a mate. Most birds mate for one season only. But some have the same mate for more than a year or for life. These birds include many albatrosses, penguins, ravens, storks, swans, and terns. In other species, such as the common yellowthroat and red-winged blackbird, a male may have a pair bond with more than one female at a time. Each female has a nest within the male’s territory.

Building a nest.

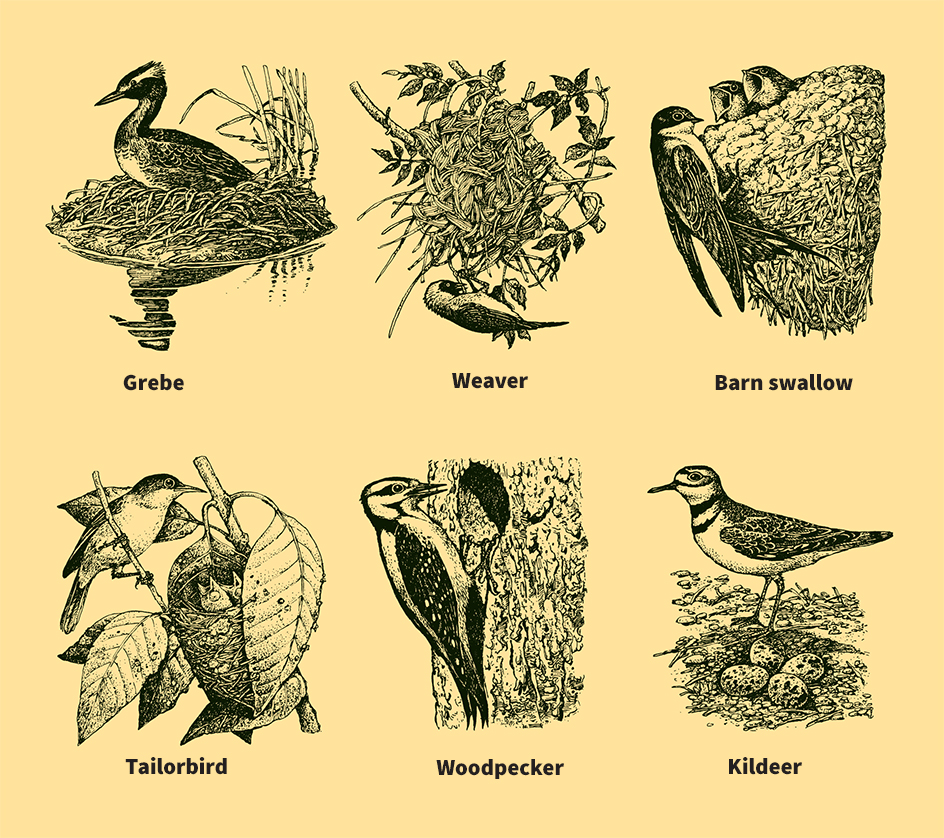

Most kinds of birds build nests, which vary from simple to elaborate structures. The female typically does all or most of the work. If the males help, they chiefly provide building materials.

Most bird nests are bowl- or saucer-shaped structures of such materials as twigs, grass, and leaves. Birds build such nests on the ground, in bushes and trees, on ledges, and in holes. The nests of the smallest hummingbirds measure only about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) high. Ospreys build nests as thick as 6 feet (1.8 meters). Many birds cement the building material together with sticky substances. Blue jays and American robins use mud. Hummingbirds and gnatcatchers use sticky threads from spider webs. Swifts use their own thick, gummy saliva. Hardened saliva not only holds the nest together but also cements it to the nesting place, such as the wall of a cave or the inside of a chimney.

Some kinds of birds do not build bowl- or saucer-shaped nests. Most woodpeckers and kingfishers nest in holes that they make by using their bill as a digging tool. Woodpeckers dig the holes in dead trees. Kingfishers, motmots, and bank swallows dig nests in banks of sand or clay. Many birds make nests that are completely enclosed except for a small entrance. Weavers of tropical Africa use their bill and feet to weave such nests of grasses and plant fibers. The nests hang from tree branches or reeds. Some kinds of swallows construct enclosed nests of mud cemented to the sides of cliffs, caves, hollow trees, or even houses and office buildings.

Some birds cooperate in building an enormous community nest in which each pair has its own “apartment.” Such birds include several species of African weavers, the monk parakeet of South America, and the palmchat of the Caribbean region.

Many birds do not build a nest. Most falcons and nightjars, for example, simply lay their eggs on bare ground. Certain other birds nest in hollow trees, in nest boxes, in holes in the ground, or in the abandoned nests of other birds. Such birds include bluebirds, house sparrows, parrots, tree swallows, wrens, and some owls. Starlings often chase other birds from the birds’ nests and then use the nests themselves. The brown-headed cowbird and European cuckoo also lay their eggs in the nests of other birds.

Laying and hatching eggs.

Birds reproduce sexually. In sexual reproduction, a sperm (male sex cell) unites with an egg (female sex cell) in a process called fertilization. The fertilized egg develops into a new individual. The first stage in this development is the formation of an embryo. In almost all mammals, the embryo develops inside the body of the female. In birds, the female lays the fertilized egg before the embryo starts to grow. After the egg has been laid, it must be incubated (kept warm) for the embryo to develop into a chick.

Female birds lay one egg at a time. Usually, the female produces an egg every day or two. The entire set of eggs produced, called a clutch, varies in size. Most birds lay clutches of 2 to 8 eggs. A few birds, including pheasants and grouse, lay clutches of 15 or more eggs. Some species, including albatrosses, petrels, and many auks, penguins, and pigeons, have a clutch of one.

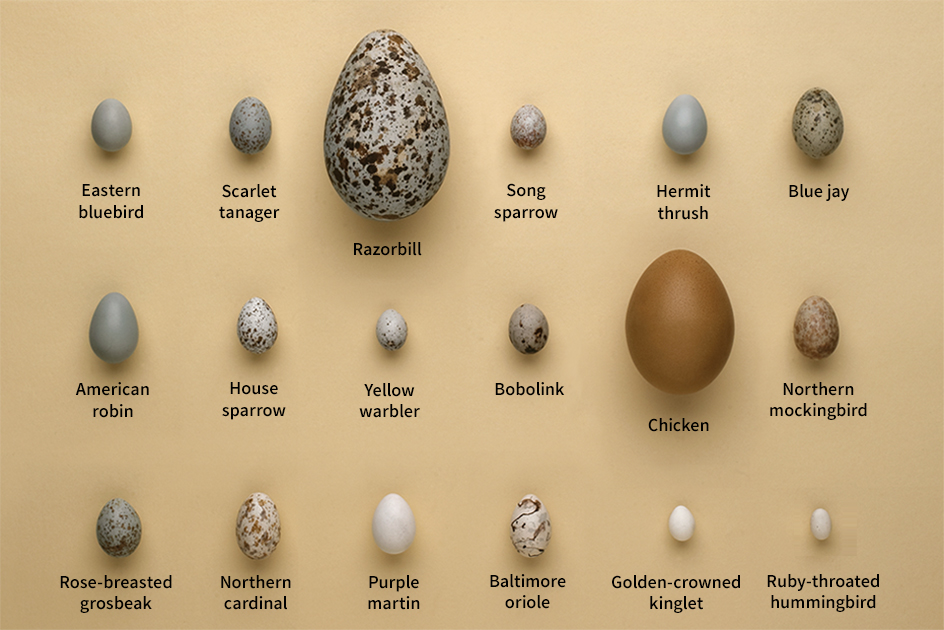

Birds’ eggs differ greatly in size. Among living birds, hummingbirds lay the smallest eggs, and ostriches lay the biggest. A hummingbird egg weighs less than 1/50 ounce (0.6 gram). An ostrich egg weighs about 3 pounds (1.4 kilograms). Eggs of the extinct elephant bird, a larger relative of the ostrich, could weigh up to 20 pounds (9.1 kilograms). Such eggs are the largest known single cells in any animal. Most birds’ eggs are shaped like domestic chicken eggs, but some species produce eggs of slightly different shape. For example, the eggs of auks and certain other cliff-nesting species are sharply pointed at one end, preventing them from rolling off the cliff. Many birds have plain-colored eggs. The eggs of most ground nesters are camouflaged with speckles and other markings. Such markings occur because of chemical pigments deposited in the shell during its development.

Nearly all birds incubate their eggs by sitting on them. In many species, such as pigeons and starlings, the parents take turns incubating the eggs. Among other kinds of birds, only the female incubates. In a few species, including phalaropes, the male does all the incubating. The megapodes, a group of ground-dwelling birds in Australia, Indonesia, and the Pacific Islands, do not incubate their eggs by sitting on them. In many megapode species, males and occasionally females build a large pile of rotting vegetation. The female lays an egg in a hole at the center of the mound and then covers the egg with vegetation and soil. Heat from the rotting vegetation warms the egg. Other megapode species bury their eggs in sandy beaches and let solar heat warm them. Still others warm their eggs by burying them near volcanoes. These areas receive much geothermal heat, or heat produced from within the earth.

The incubation period ranges from 10 days in some small songbirds to 80 days in large albatrosses. By the end of this period, the embryo has developed into a chick and is ready to hatch out of the egg. Many chicks have a hard, sharp bump called an egg tooth near the tip of the bill. A chick uses the egg tooth to break through the shell. The egg tooth falls off or gradually disappears after the chick hatches. Some chicks have egg teeth at the tips of both halves of the bill.

Caring for the young.

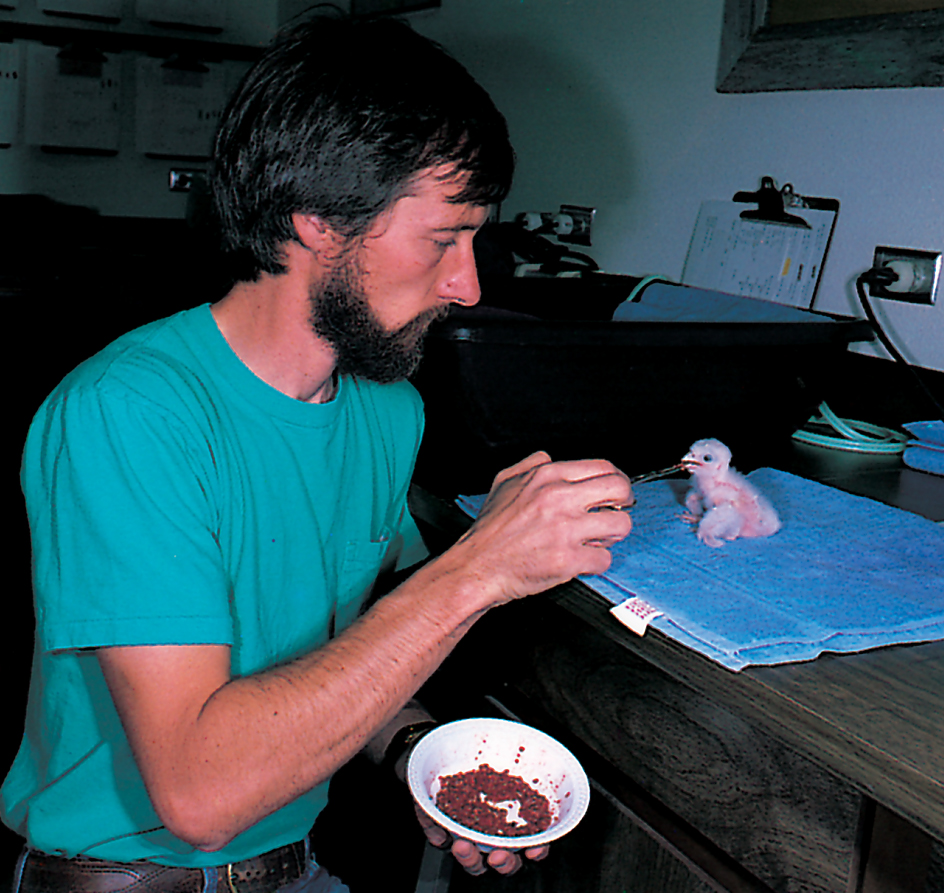

Most newborn chicks are blind, practically featherless, and so weak-legged they cannot stand. Such birds are called altricial << al TRIHSH uhl >> . They include baby hummingbirds, kingfishers, pelicans, swifts, and all songbirds. In other species, the newborn chicks can see, and they have a covering of fine down and strong legs. These birds are called precocial << prih KOH shuhl >> . They include all baby chickens, ducks, geese, megapodes, ostriches, quails, swans, and turkeys. Precocial young can walk from the nest and start to hunt for food a few hours or days after hatching. Altricial young must remain in the nest far longer and be cared for by their parents.

In most cases, the parents of altricial chicks feed them juicy insects or other foods containing much moisture. Gradually, the babies see, grow feathers, and become stronger. They then begin to stand at the edge of the nest and stretch their wings. In time, they start to make short, clumsy flights. All birds fly without being taught. But many need months of practice to fly skillfully.

In certain birds, other individuals of the same species help the parents raise the young in the nest. This behavior is called cooperative breeding. The helpers are often the young from a previous year’s clutch of the same parents. In North America, cooperative breeding occurs in such birds as the acorn woodpecker, Florida scrub jay, groove-billed ani, and red-cockaded woodpecker.

Brood parasites.

Some birds rely on birds of other species to raise their family. Such birds are known as brood parasites. The foster parents are called hosts. Brood parasites include the brown-headed cowbird and European cuckoo. Females of these species lay eggs in the nests of songbirds, next to the eggs of the hosts. The hosts not only hatch the eggs of the brood parasites with their own but also raise the chicks. Chicks of most brood parasites survive by dominating the hosts’ young and gaining more food from the host parents.

Bird migration

The migration of birds remains one of the most fascinating and least understood events in nature. Birds are not especially strong. Yet numerous species migrate tremendous distances, often flying many hours or days without stopping. The blackpoll warbler, a North American bird no bigger than a sparrow, flies nonstop nearly 2,500 miles (4,023 kilometers) to its winter home in South America. The journey takes nearly 90 hours.

Many birds migrate farther than the blackpoll warbler, but only large birds fly farther without stopping. Arctic terns are the champions of long-distance migration. They fly about 11,000 miles (17,700 kilometers) from their breeding grounds in the Arctic to their winter home in the Antarctic. The birds return to the Arctic a few months later. They thus travel about 22,000 miles (35,400 kilometers) in less than a year. Many birds migrate enormous distances yet return to exactly the same nesting places every year. Scientists have learned much about why, where, and how birds migrate. But many questions remain unanswered.

Why birds migrate.

In many parts of the world, the foods that birds eat become scarce during certain seasons of the year. Many birds, such as insect eaters, would starve if they had to remain in such places through the unfavorable season. This situation is especially true of regions with cold, snowy winters. The majority of birds that nest in these regions migrate to warmer climates in fall. They return in spring, when the weather warms up again. Many parts of the tropics have a dry season and a rainy season each year. Food and drinking water may become scarce during the dry season. Many birds avoid such shortages by migrating to moister parts of the tropics at the start of each dry season and returning after it ends. Other birds, which prefer to nest in dry areas, migrate to drier parts of the tropics during the rainy season.

Birds that do not migrate during the unfavorable season are species that can survive on the available food. Most birds that remain in northern areas over the winter live mainly on seeds, tree buds, and dry berries. Such birds include bobwhites, cardinals, grouse, and several kinds of finches and sparrows. Insects are scarce in northern regions during the winter. Most insect-eating birds therefore migrate. The majority of those that remain are small birds that live mainly on insect eggs and the developing young of insects. These birds include chickadees, nuthatches, titmice, and woodpeckers.

Although birds migrate to survive, the factors that actually trigger their migrations are much more difficult to explain. For example, many northern species leave their summer home while the weather is still warm and the food supply plentiful. The birds cannot know that the weather will turn cold and that food will become scarce.

Bird migrations are probably regulated by the glandular system. The glands produce chemical substances called hormones. Changes in hormone production stimulate the birds to migrate. Among some northern species, hormone production is affected by the length of daylight. As the daylight hours shorten, hormonal changes cause the birds to prepare for their migratory flight south. However, changes in daylight only partly explain the timing of migrations. Different species may depart from the same area at different times. In addition, the same species may not depart at the same time every year. The exact timing of migrations depends not only on the amount of daylight but also on such conditions as the weather and the food supply.

Where birds migrate.

The great majority of birds that migrate travel in a generally north-south direction. Most birds that breed in Canada and the northern part of the United States fly south for the winter. Many migrate as far as tropical South America. Some even fly all the way to Argentina, Uruguay, or southern Chile. Many birds that breed in the United Kingdom and northern Europe migrate to southern Africa to spend the winter. The seasons south of the equator are opposite those in the north. Therefore, North American birds that migrate to southern South America and European birds that migrate to southern Africa arrive in time for summer in those regions. These birds and many of the native species fly northward at the start of the southern winter. However, no native South American birds migrate to North America. They fly only as far north as the tropics, spend the winter there, and then return south for the summer.

Certain species of migratory birds do not travel in an exact north-south direction. For example, several species that breed in western North America, such as avocets and white pelicans, migrate southeast to winter in Florida. Birds that breed on high mountain slopes may simply move down into the warmer valleys for the winter. In North America, such birds include the common raven, rosy finch, and mountain quail. Some birds make regular seasonal migrations within the tropics, but little is known about these movements.

Many species of birds migrate along the same routes. Birds tend to follow such physical features as coastlines, mountain ridges, and river valleys. Heavily traveled routes are known as flyways. North America, for example, has four main flyways: (1) the Pacific Flyway, along the Pacific coast; (2) the Central Flyway, which follows the Rocky Mountains; (3) the Mississippi Flyway, which follows the Mississippi River; and (4) the Atlantic Flyway, along the Atlantic coast. But these flyways are only approximate, and many birds migrate outside them. Some species use different flyways in different migrations. Such variations occur for many reasons. For example, food sources may prove abundant in one flyway during the fall and in a different flyway in spring. Also, some species alter their migratory routes to go with the prevailing wind patterns. Scientists have designated flyways chiefly to divide the continent into zones for administering laws that deal with the hunting of migratory birds.

How birds migrate.

Some species of birds migrate in small groups. Other species fly in flocks composed of as many as several million birds. Most small birds travel at night and stop to feed and rest during the day. Most large birds do the opposite. Birds that feed on flying insects, such as swallows, nighthawks, and swifts, often migrate during the day so they can feed as they migrate. The majority of migrating birds fly at altitudes of about 3,000 to 6,000 feet (914 to 1,829 meters). But some types, including various shorebirds and geese, have been detected by radar at 20,000 feet (6,096 meters) or higher.

The question of how migrating birds find their way to the same destination every year has long puzzled and fascinated scientists. Scientific research has provided several answers to this question. Birds that migrate over land probably follow landmarks, such as river valleys and mountain ranges. Day migrants can use the sun to find directions. Experiments have shown that some birds can navigate by using the stars. These birds orient themselves by observing the rotation of the stars at night. When landmarks, the sun, or the stars are not visible, birds may use the earth’s magnetic field, an invisible region of magnetic force, to guide them. However, such theories raise even more puzzling questions. To navigate by magnetic fields, birds must have highly specialized and highly complicated sensory organs to sense magnetism. Scientists are working to discover what these sensory organs are and how they might function.

The bodies of birds

The bodies of birds are adapted for flying. Even such flightless birds as penguins and ostriches have some features of their flying ancestors. All birds have a generally streamlined body and exceptionally lightweight skeletons, feathers, and internal organs.

External features

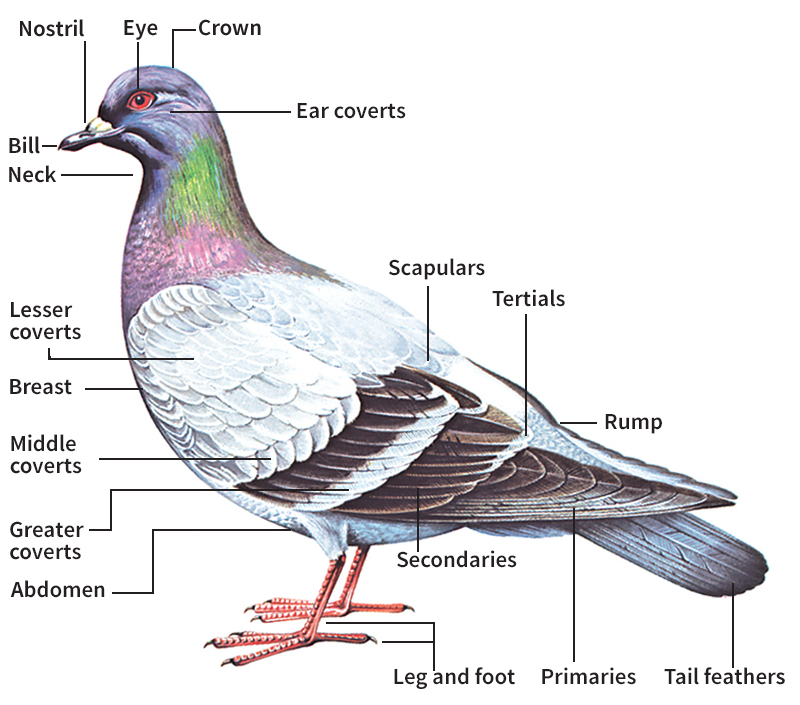

The most striking external feature of a bird is its feathers. Feathers cover all the main parts of a bird’s body except the eyes, bill, legs, and feet. In some species, including some owls, even the legs and feet have feathers.

Feathers.

Birds possess from 940 to 25,000 feathers. Most feathers have a stiff central shaft, on each side of which is a flat vane. The vane consists of hundreds of slender parallel branches from the shaft. These branches, or barbs, each have dozens of tinier branches called barbules. Variations in the shape of the shaft, barbs, and barbules create a wide variety of feather types.

The largest feathers are the long flight feathers of the wings and tail. Flight feathers near the wing’s tip are called primaries. Those closer to the body are known as secondaries. A layer of smaller feathers called coverts covers the base of the flight feathers. In flight feathers, the barbules have microscopic hooks and grooves that zip together and hold neighboring barbs tightly to one another. Other vaned feathers called contour feathers cover the bodies of most birds.

In addition to vaned feathers, some birds have down feathers or plumes or both of these types. Most down feathers have a short shaft and soft, fuzzy barbs that are not connected into vanes. The barbules of down feathers lack the microscopic hooks and grooves of vaned feathers. Many water birds have a thick coat of down under the vaned feathers. Plumes are generally long feathers with flexible shafts and barbs. They may grow from different body parts and are used in courtship displays.

In many species of birds, the male has more brightly colored feathers than does the female. In a few species, females have the more colorful plumage. In other species, the male and female look alike.

Birds shed their feathers at least once a year and grow a new set. This process, called molting, generally occurs after the breeding season and enables birds to replace worn feathers. Most birds that molt twice a year have a different appearance in different seasons. The majority of these birds, including grebes and loons, are brightly colored in spring and summer and dull in fall and winter. In some species, including many ducks, only males alternate between a colorful and dull phase.

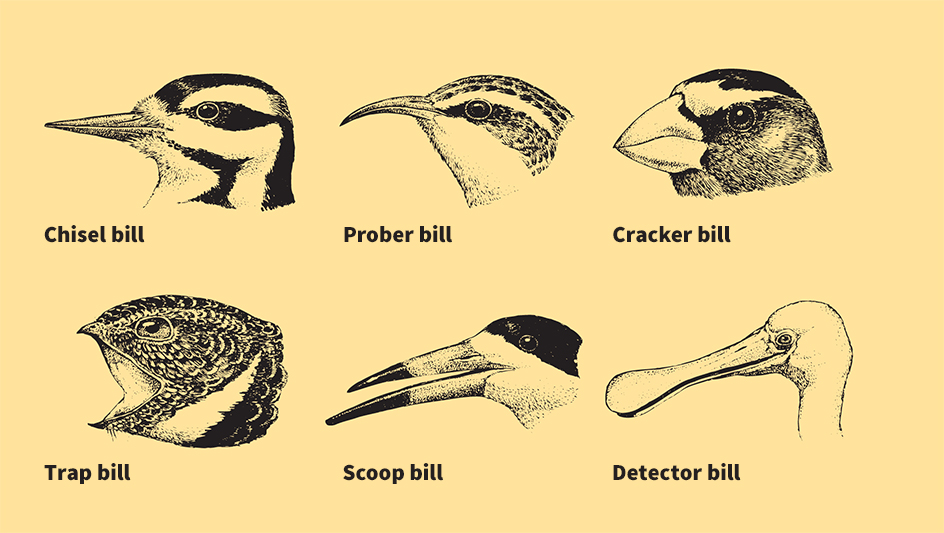

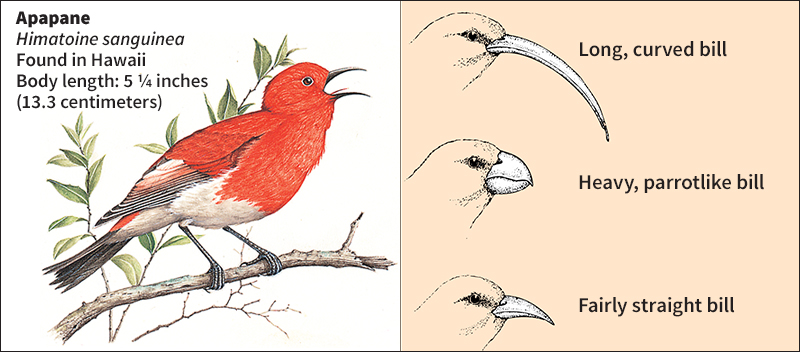

Bills

of birds differ mainly according to how the birds feed. Finches, grosbeaks, and most other seed-eating birds have a hard, cone-shaped bill, which they use like a nutcracker. Woodpeckers possess a chisellike bill, which they use to bore into trees to find insects.

Flamingos and many ducks eat plant and animal matter that floats on water. These birds have a broad bill with hundreds of tiny filters along the edges. This bill enables the birds to take big mouthfuls of water. The filters along the edges of the bill trap the food particles and let water drain away. Most fish-eating birds, such as anhingas, herons, and terns, have a long, pointed bill, which they use to spear fish. Pelicans use their unusually large bill and throat pouch to scoop fish from the water. Some land birds, such as hornbills and toucans, have a large, brightly colored bill. But most hornbills and toucans are fruit eaters. The huge size and bright colors of the bill are apparently unrelated to the method of feeding. They probably serve mainly for display.

Legs and feet.

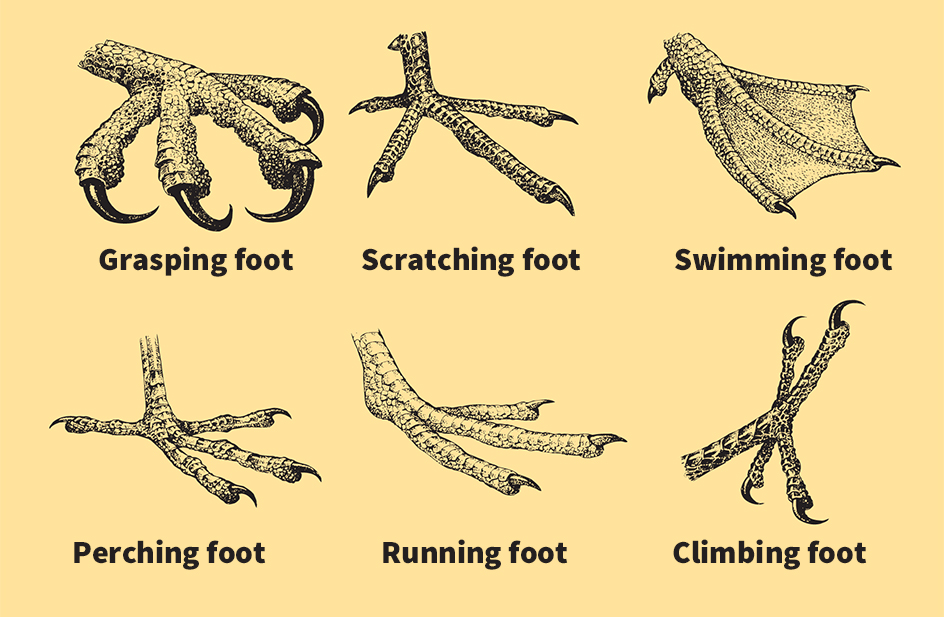

Although all birds have two legs and two feet, the size and structure of the limbs differ greatly among various species. Birds that spend most of their time in the air have exceptionally short legs. The legs of most tree climbers are also shorter than the average. On the other hand, most wading birds and fast runners have especially long legs.

The great majority of birds have four toes on each foot. In most species, including all songbirds, three toes point forward and one points backward. A perching bird steadies itself by curling the hind toes around a branch or other perch. Some birds that are good climbers, including cuckoos, parrots, and woodpeckers, have two toes pointing forward and two pointing backward. The hind toes help provide an extra grip for the birds as they climb. Emus and most other flightless, fast-running birds have lost the hind toe and have only three toes on each foot. The ostrich is the only two-toed bird.

Many swimming birds have webs of skin connecting their toes. The webbing enables the birds to use their feet like paddles. In such birds as ducks and gulls, the webbing connects only the three front toes. Cormorants, pelicans, and related birds have all four toes connected by webs. Instead of webbing, coots, grebes, and phalaropes have broad, paddlelike toes. Gallinules and screamers are also good swimmers, but their feet differ little from those of four-toed land birds.

Birds have a claw at the tip of each toe, but claws are not equally prominent in all species. Birds with large, sharp, curved claws include birds of prey and birds that cling to vertical surfaces, such as swifts and woodpeckers. Most running birds have short, blunt claws.

Skeleton and muscles

A bird’s skeleton is lightweight but strong. Many bones that are separate in mammals are fused (joined together) in birds. The fused bones give the skeleton exceptional strength. The skeleton is lightweight chiefly because many of the bones are hollow.

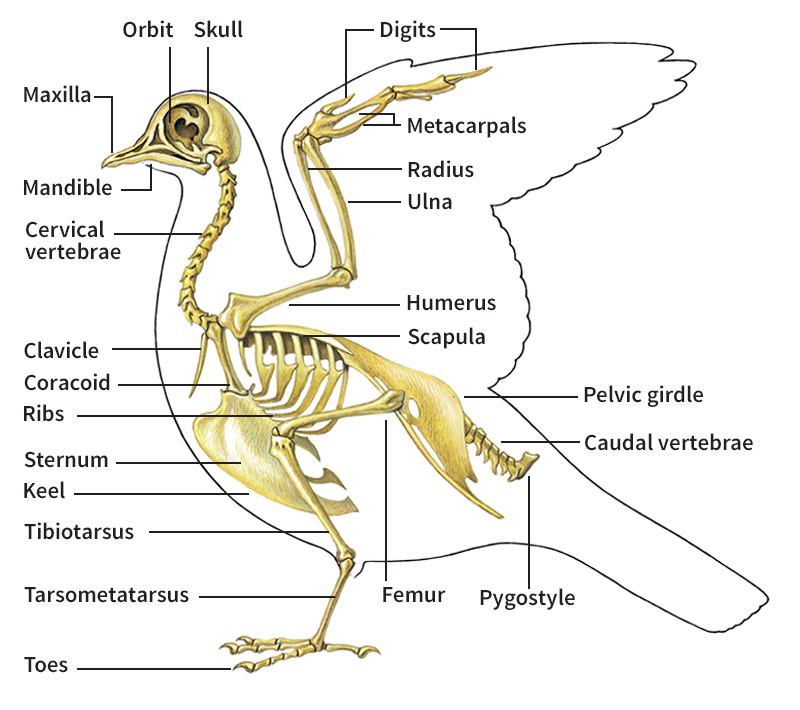

The wings of a bird correspond to the arms or forelimbs of human beings and other tetrapods (four-limbed animals). Each wing has three main parts: (1) a single bone in the upper arm called the humerus, (2) a pair of bones, the radius and ulna, in the forearm, and (3) a hand with only three fingers. Primary flight feathers are attached to the bones of the hand, and secondary flight feathers are attached to the ulna.

A bird’s chest includes a sternum (large breastbone) with a prominent center ridge called a keel. The major wing muscles are attached to the keel. Birds also have a wishbone, consisting of the fused clavicles (collarbones).

In birds that fly, the largest muscles are those that move the wings. Most birds have strong leg muscles, which are especially well developed in fast runners. Small muscles at the base of each feather enable a bird to maneuver its feathers, fluff them, display them, and keep the wind from blowing them around.

Senses

Birds have keen senses of sight and hearing. However, their senses of smell, taste, and touch are less well developed.

Sight.